Archives, January, 2010

Friday, January 29th, 2010

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

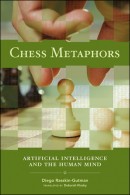

Garry Kasparov reviews a book about chess and artificial intelligence, a springboard for his thoughts about the state of the game and technology. Fascinating. . . . Matt Ridley reviews a “witty and incisive” book about the “quest to end aging.” . . . Alice Kaplan writes a wonderfully brainy-but-breezy essay about “volumes assessing literary reputations during the years of the Nazi occupation of France.” . . . Richard Posner writes a long, characteristically intelligent piece about the history of miscegenation laws in the U.S. (“People take pride in being descended from Mayflower passengers, or from Revolutionary War veterans, though after a very few generations the traits that distinguished an honored ancestor, even if genetic, disappears in the genetic reshuffling that occurs in every new generation.”) . . . The Economist judges that Peter Carey’s latest novel, a fictional retelling of Tocqueville’s travels in America, “has all the quirky qualities that we have come to expect from Peter Carey: a winding narrative, a mass of vivid historical detail, and some very lively writing.” . . . The Guardian calls Jon McGregor’s new novel, Even the Dogs, “a [powerful] fragmentary group portrait” of addicts and vagrants who move in and out of an empty flat over several years. . . . Jeff VanderMeer calls a new novel about Depression-era bank robbers “a rip-roaring yarn that manages to be both phantasmagorical and historically accurate. In its labyrinthine, luminous narrative, reminiscent of Michael Chabon’s best fiction, readers will find powerful parallels to the present-day.”

Garry Kasparov reviews a book about chess and artificial intelligence, a springboard for his thoughts about the state of the game and technology. Fascinating. . . . Matt Ridley reviews a “witty and incisive” book about the “quest to end aging.” . . . Alice Kaplan writes a wonderfully brainy-but-breezy essay about “volumes assessing literary reputations during the years of the Nazi occupation of France.” . . . Richard Posner writes a long, characteristically intelligent piece about the history of miscegenation laws in the U.S. (“People take pride in being descended from Mayflower passengers, or from Revolutionary War veterans, though after a very few generations the traits that distinguished an honored ancestor, even if genetic, disappears in the genetic reshuffling that occurs in every new generation.”) . . . The Economist judges that Peter Carey’s latest novel, a fictional retelling of Tocqueville’s travels in America, “has all the quirky qualities that we have come to expect from Peter Carey: a winding narrative, a mass of vivid historical detail, and some very lively writing.” . . . The Guardian calls Jon McGregor’s new novel, Even the Dogs, “a [powerful] fragmentary group portrait” of addicts and vagrants who move in and out of an empty flat over several years. . . . Jeff VanderMeer calls a new novel about Depression-era bank robbers “a rip-roaring yarn that manages to be both phantasmagorical and historically accurate. In its labyrinthine, luminous narrative, reminiscent of Michael Chabon’s best fiction, readers will find powerful parallels to the present-day.”

Friday, January 29th, 2010

Mike Riggs writes about going to find J. D. Salinger’s house with a couple of friends. A piece:

A different man, with a bagpipe on his hip and a black lab at his side, had taunted us for nearly six hours, alternately giving us clues as to which house belonged to Salinger and insulting us. “You think you’re the first people to come looking for Mr. Salinger?” He said when we pulled alongside him in his driveway. “Go home.” The next time around the bend, “You can’t see his house from the road.” Then, “If you admire him so much, respect his desire for privacy;” followed by, “I can comfortably walk the distance between our two houses;” and, “Long drive back to Florida. Better get started now.”

Eventually, the bagpiper stopped responding to our questions about Salinger. And because we were lost, yet still committed to the hunt, we agreed to talk about other things in between bouts of goose-chasing. The black flies. The weather. The efficiency of the Cornish fire department. But never about Salinger. When we pulled up to the bagpiper’s yard for the last time, he simply pointed to the barn across the dirt road. “I raised that barn myself,” he said, then put the bagpipe reed back in his mouth and honked his way through his front door.

Friday, January 29th, 2010

This list at Life of “literary drunks & addicts” casts a wide and somewhat ungenerous net. (It includes Louisa May Alcott because she got hooked on morphine after contracting typhoid fever as a nurse during the Civil War.) But it was worth scrolling through for some choice quotes about the drinking habit.

This list at Life of “literary drunks & addicts” casts a wide and somewhat ungenerous net. (It includes Louisa May Alcott because she got hooked on morphine after contracting typhoid fever as a nurse during the Civil War.) But it was worth scrolling through for some choice quotes about the drinking habit.

For instance, Brendan Behan: “I only take a drink on two occasions: when I’m thirsty and when I’m not.”

And one of Dorothy Parker’s famous lines: “One more drink and I’ll be under the host.”

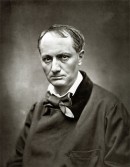

But if pith isn’t your thing, there’s the far more blunt Charles Baudelaire (pictured above, looking just as you’d expect the person who issued this quote to look): “Always be drunk. . . . Get drunk militantly. Just get drunk.”

Thursday, January 28th, 2010

The full Salinger obituary is up at the New York Times.

And the Paris Review points to an interview in its archives, in which famed publisher Robert Giroux talks about the handshake agreement he had with Salinger to publish The Catcher in the Rye, and how he quit when those above him wouldn’t honor it:

Gene said, “The kid is disturbed.” I said, “Well, that’s all right. He is, but it’s a great novel.” He said, “Well, I felt that I had to show it to the textbook department.” “The textbook department?” He said, “Well, it’s about a kid in prep school isn’t it? I’m waiting for their reply.” I said, “It doesn’t matter what their reply is, Gene. We have a contract for the book.” I felt like saying, “You son of a bitch, this is the greatest insult to me that could ever be.” The textbook people’s report came back, and it said, “This book is not for us, try Random House.”

Thursday, January 28th, 2010

A commenter at the New York Times, echoing others, is already asking for his children to “do the right thing and publish much of the material he has been hoarding away for the last 4 decades.” And we thought the debate over Nabokov’s Laura created a stir.

Thursday, January 28th, 2010

Did Thomas Edison predict the Kindle and iPad?

“Nickel will absorb printer’s ink,” [Edison said.] “A sheet of nickel one twenty-thousandth of an inch thick is cheaper, tougher, and more flexible than an ordinary sheet of book-paper. A nickel book, two inches thick, would contain 40,000 pages. Such a book would weigh only a pound. I can make a pound of nickel sheets for a dollar and a quarter.”

There is virtually no evidence that Thomas Edison ever followed up on this idea. He probably thought it through and realized that it would be impractical and cause injury: Imagine flipping through a steel-covered book with leaves of nickel to page 14,237. Next, visualize the bloody mess now passing for the tip of your thumb or index finger. Then consider, as with the compact edition of the O.E.D., that you’ll require a high-power magnifying glass to read the print.

It’s not, however, all bad. A one-pound, two-inch thick all-metal book is well-nigh indestructible. Drop it from the roof of a building and it may dent but remain functional. Try that with a Kindle or iPad.

Wednesday, January 27th, 2010

From This Was Racing by Joe H. Palmer (1953), the subject of the next Backlist feature, which will be published in the near future:

From This Was Racing by Joe H. Palmer (1953), the subject of the next Backlist feature, which will be published in the near future:

A thin file of racers was stepping slowly out from beneath the crowded stands at Churchill Downs. A band was playing “My Old Kentucky Home” with intense feeling and a trumpet which was a half-tone flat. A hundred thousand people, give or take a half dozen, were straining for a glimpse of the Derby parade. There were flashes of crimson and gold and purple silk under a watery May sunshine, as a dozen or so jockeys tried to ride to the post with what they hoped was nonchalance.

At the moment a dozen or so horses held the nation’s sporting interest, the pick of a crop of perhaps 8,000 foals. A quarter-hour later one would stand garlanded and restive in the presentation enclosure, as the others went back beaten to their barns. The winner might be 5 to 2 in the mutuels, but he was 8,000 to 1 on a spring night three years earlier, when his dam heaved up from a straw-filled stall and had a look at him.

Outside the race track there was a tense, expectant world, waiting crouched over its radios, and occasionally sending one of the children down to the drug store for razor blades. Men paused over their lobster pots on off-shore Maine to adjust the portable. For that fleeting instant, no one cared what Rita or Princess Elizabeth was doing. It was, you understand, a very solemn moment.

“I wonder,” remarked John McNulty, of the New Yorker, “what would happen if a convention were ever held in Mecca. How would you write a lead?”

The band had got to “bye and bye hard times come a-knockin’” before this was figured out. Mr. McNulty had evidently worked on a copy desk somewhere, and under his recoiling fingers had come many a story beginning, “Indianapolis was the Mecca of auto-racing enthusiasts today when—”; “Philadelphia became the Mecca of the services today when Army and Navy—”; “Oberammergau became the Mecca of Southern Bavaria today when—” and others of what is called an ilk.

All the same, and with all proper apologies, Louisville, Ky., is about to become the Mecca of. The Gateway to the South (it says on the bridges) will brace itself against successive waves of visitors with no noticeable gift for quietude, and the tempo will rise until late on the afternoon of the first Saturday in May. On the following afternoon Louisville could be grouped around St. Anthony’s hut in the Thebaid without disturbing his devotions. This tourist often stays over an extra day, just to listen to the silence.

Wednesday, January 27th, 2010

If you haven’t bookmarked the site Letters of Note, you should. This recent entry by Mark Twain was written to a salesman who had attempted to sell Twain bogus medicine. It includes this line: “The person who wrote the advertisements is without doubt the most ignorant person now alive on the planet; also without doubt he is an idiot, an idiot of the 33rd degree, and scion of an ancestral procession of idiots stretching back to the Missing Link.” . . . A 1973 book of photos of New York City graffiti (with an essay by Norman Mailer) is being reissued. . . . It takes six people to lift the world’s biggest book, and it will be on display this summer at the British Library. . . . Maud Newton has opened a comments thread to ask writers what they did before they wrote, or while they wrote, or what they would like to do if they didn’t write. (Newton herself has an idea for a private eye firm with the TV-series-ready name of Grasso & Neutron.) . . . Lawrence Lessig on “Google, copyright, and our future.” . . . Flavorwire lists five good sites for book-related videos. . . . Mark Athitakis investigates the long-standing notion of a “typical New Yorker short story.” . . . A very creepy, but very effective book cover (via Casual Optimist).

If you haven’t bookmarked the site Letters of Note, you should. This recent entry by Mark Twain was written to a salesman who had attempted to sell Twain bogus medicine. It includes this line: “The person who wrote the advertisements is without doubt the most ignorant person now alive on the planet; also without doubt he is an idiot, an idiot of the 33rd degree, and scion of an ancestral procession of idiots stretching back to the Missing Link.” . . . A 1973 book of photos of New York City graffiti (with an essay by Norman Mailer) is being reissued. . . . It takes six people to lift the world’s biggest book, and it will be on display this summer at the British Library. . . . Maud Newton has opened a comments thread to ask writers what they did before they wrote, or while they wrote, or what they would like to do if they didn’t write. (Newton herself has an idea for a private eye firm with the TV-series-ready name of Grasso & Neutron.) . . . Lawrence Lessig on “Google, copyright, and our future.” . . . Flavorwire lists five good sites for book-related videos. . . . Mark Athitakis investigates the long-standing notion of a “typical New Yorker short story.” . . . A very creepy, but very effective book cover (via Casual Optimist).

Tuesday, January 26th, 2010

I’m planning to publish more reviews of translated books on the site this year. A couple are already in the pipeline. Translation may be a small percentage of the American market, but it’s one of those subjects for which the Internet has been a blessing.

Among recent chatter, Lewis Manalo, the buyer for Idlewild Books, a terrific store in New York, writes about the shortage of good stories from even English-language origins making it to the U.S.:

Groups such as Words Without Borders encourage works in translation. Small presses such as Archipelago and Open Letter specialize in printing literature from other languages. But as a bookseller, to concentrate on translation misses the point: readers like a good story. And many of those stories unavailable in the United States are already in English.

For example, the author I have always gotten the most requests for whose work is unavailable in the United States is the Australian Bryce Courtenay. Despite Courtenay being one of the bestselling authors in the English-reading world, until Idlewild began selling imports from the U.K., the only title of his I could offer customers was The Power of One. That book certainly deserves to be read, but why are American readers denied Courtenay’s historical novel Jessica or his latest bestseller, The Story of Danny Dunn?

Chad Post, of Open Letter (and Three Percent, the publisher’s blog), wrote three recent posts about translation “having a moment”: Part one, part two, and part three.

Jessa Crispin recently reviewed a new anthology of European fiction, and I think she’s right to temper the criticism of American readers, typified by Nobel Prize judge Horace Engdahl, who famously said Americans were “too insular”:

[Engdahl] made a true statement, but not a profound one. It presupposes that other cultures are not insular. Are the Nigerians really that interested in the literature coming out of Denmark? The Latvians in Filipino poetry? No. Each culture is primarily interested in its own subject, plus whatever is coming out of America. With that arithmetic, we are even with everyone else. We just don’t have a market larger than our own to aspire to.

Again, not an argument against translation. Just some tempering. Now we can go expand our horizons back at Three Percent, which is writing a post a day about the longlist of finalists for this year’s Best Translated Book Award.

Monday, January 25th, 2010

A continuing series that highlights books recently acquired by publishing houses for future release. Each post features a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

The Cherry:

Joe Jackson’s Atlantic Fever: Lindbergh, His Competitors, and Five Deadly Weeks in the Race to Conquer the Atlantic, set during five incredibly tense weeks in the Spring of 1927, one of those magical time windows in history opened in which daredevils on both sides of the Atlantic were all on the cusp of being the first to cross the ocean in solo flight - a time fraught with danger, death, innovation, larger than life personalities, and a little-known pilot who would beat them all to change history.

The Pit:

Jen Hatmaker’s Out of the Spin Cycle: Devotions to Lighten Your Mother Load, offering forty things Jesus doesn’t expect moms to do on their own; a devotional for the woman inside the mom — the Bible student, the learner, the world changer.

Friday, January 22nd, 2010

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Peter Lopatin says that Rebecca Newberger Goldstein’s 36 Arguments for the Existence of God is “a captivating, original, and at times riotously funny novel” that “does justice to the depth of the problem of reconciling a scientific worldview with the insistent yearning for transcendence.” . . . Julian Baggini surveys four new books about happiness. . . . Paul Mason reviews two books about the financial crisis, one by Joseph Stiglitz and the other by John Lanchester. . . . Tom Shone says that a new book about James Cameron is “less a biography proper than a set visit by someone who got carried away with access to the great and mighty Oz.” . . . Blake Morrison recommends Antonia Fraser’s new memoir about her marriage to Harold Pinter. (“Those hoping for bedroom tattle will be disappointed. The book is intimate without being confessional, and on certain subjects [Fraser] prefers to say nothing. But she’s not so discreet as to be dull, and there’s a lot of humor.”) . . . Ludovic Hunter-Tilney says that Nick Flynn’s second memoir, The Ticking is the Bomb, melds the political and the personal in a way that is “profoundly unconvincing,” not to mention “banal”: “Strip away the highbrow references to Paradise Lost and so on, and the book’s message is essentially that of a Batman movie: we all have a dark side.”

Peter Lopatin says that Rebecca Newberger Goldstein’s 36 Arguments for the Existence of God is “a captivating, original, and at times riotously funny novel” that “does justice to the depth of the problem of reconciling a scientific worldview with the insistent yearning for transcendence.” . . . Julian Baggini surveys four new books about happiness. . . . Paul Mason reviews two books about the financial crisis, one by Joseph Stiglitz and the other by John Lanchester. . . . Tom Shone says that a new book about James Cameron is “less a biography proper than a set visit by someone who got carried away with access to the great and mighty Oz.” . . . Blake Morrison recommends Antonia Fraser’s new memoir about her marriage to Harold Pinter. (“Those hoping for bedroom tattle will be disappointed. The book is intimate without being confessional, and on certain subjects [Fraser] prefers to say nothing. But she’s not so discreet as to be dull, and there’s a lot of humor.”) . . . Ludovic Hunter-Tilney says that Nick Flynn’s second memoir, The Ticking is the Bomb, melds the political and the personal in a way that is “profoundly unconvincing,” not to mention “banal”: “Strip away the highbrow references to Paradise Lost and so on, and the book’s message is essentially that of a Batman movie: we all have a dark side.”

Thursday, January 21st, 2010

Judith Gurewich, Publisher of Other Press, writes about why she no longer publishes psychoanalytic books:

Judith Gurewich, Publisher of Other Press, writes about why she no longer publishes psychoanalytic books:

Today, the most meaningful and revealing “analysis” takes place in good fiction and creative non-fiction. We have moved into a new era, when the old psychological insights have begun to feel like those antibiotics that become ineffectual because of bacterial resistance. On the other hand, literature, by the nature of its calling, is continually forced to harbor elements of surprise, which in the best case grant it the power to transform its readers, leading them to new levels of enlightenment. The shift from psychoanalysis to literature was therefore a logical one to make. Freud himself would have agreed, since he believed that literature is always ahead of its time when it ponders the mysteries of the human soul. However, I don’t forget my analytic training when I edit my authors. I have found that goading them to be bolder and to the point, and face head-on what they may be afraid to confront, allows them to produce pithier works, deeper and more absorbing to read.

I’m not sure the shift “from psychoanalysis to literature,” if it’s happening, isn’t a shift back to literature, but in any case, food for thought.

Thursday, January 21st, 2010

Kevin Wilson wonders what happened to a writer named Cynthia Schad. In 1988, Wilson read a short story of hers (“Close to Autumn”) in Ploughshares. Schad was 21 at the time. Wilson’s post has been passed around (I found it via Maud Newton), but to this point there are no responses shedding light on the mystery. Here’s Wilson:

Having spent a good portion of my life feeling like I am a failure if I don’t write, that if I don’t produce stories then I’m just this lazy guy who reads comic books and argues about different kinds of barbecue, I feel a strange joy at the idea of someone, twenty-one years old, writing a nearly perfect story and moving on, doing something else. If there will never be any other stories by Cynthia Schad, there is “Close to Autumn,” and I am happy for that.

If I learn from one of you that Cynthia Schad got married, took her husband’s last name, and subsequently published dozens of books, I am going to feel very happy that I have the chance to read more of her work and, also, very stupid that I wrote this entry.

Tuesday, January 19th, 2010

One of my 2010 reading resolutions (success rate of such resolutions: approximately 27%), which I’ve mentioned before and won’t again until and unless I fulfill it (I promise), is to read Robert Walser. Over at Two Words, Scott Esposito interviews Susan Bernofsky, a Walser translator who is also at work on a biography of him. She talks about why his work appeals to her:

One of my 2010 reading resolutions (success rate of such resolutions: approximately 27%), which I’ve mentioned before and won’t again until and unless I fulfill it (I promise), is to read Robert Walser. Over at Two Words, Scott Esposito interviews Susan Bernofsky, a Walser translator who is also at work on a biography of him. She talks about why his work appeals to her:

He has a way of describing the universe that walks a fine line between the maudlin and the trivially playful–and somehow he always manages to stay right in the middle, in that sweet spot where he achieves a sort of guileless profundity that takes the reader by surprise again and again. His literary fireworks are so controlled, so sly, so knowing, and all the while he’s got such an innocent look on his face.

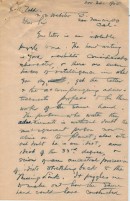

She goes on to discuss the “microscripts” that Walser produced (the interview includes an image of these scripts, which really are something):

SE: I’d also like to ask you about a work of Walser’s called The Microscripts that is forthcoming from New Directions in your translation. As I understand it, these were writings that Walser made in such a tiny script that for a long time people simply couldn’t decipher them and thought they were some personal language that Walser had invented. . . . When translating these, did you ever work directly from the microscripts, or did you rely more on a fair copy that was easier to read?

SB: We decided to reproduce full-size facsimiles of the microscripts in this collection, and when you see them, you’ll understand why there are no more than half a dozen people in the world who can read them at all (and after many months of study). It took two devoted scholars twelve years to transcribe the six volumes of these texts. That’s two years per volume! In the late ’80s I watched them at work, peering through tiny magnifying lenses and discussing each word at length. These published transcriptions are what I based the translations on. I think of Walser’s miniature writing as a sort of shorthand he developed for his rough drafts, and he wrote like this for many years. There’s been a lot of speculation about why and when he developed this technique. The writing is an enormously reduced Kurrent script–that’s an old form of German handwriting people stopped using around WWII.

Tuesday, January 19th, 2010

Robert B. Parker, best known for a series of novels starring Boston private eye Spenser, has died at 77. Sarah Weinman has quickly gathered an excellent list of relevant links. . . . M.A. Orthofer reacts to the recent and widely-linked-to Wall Street Journal piece about the “death of the slush pile.” . . . How would you like to be a famous author in the early 20th century named Winston Churchill? Bummer. . . . Book Patrol unearths a book about the sex lives of Civil War soldiers, a side of their lives “that they and their families tried to hide from posterity and Ken Burns.” . . . In 1967, Leonard Woolf was sounding a pre-Hitchens note. . . . I’ve been meaning to see An Education for a long time now. After reading Maud Newton’s description, I’d also like to read the book on which it was based. . . . Blake Morrison on the art of the first sentence. (Via Books, Inq.) . . . Illustrations from French children’s books, 1900-1949. (Via Bookslut) . . . Garth Risk Hallberg wonders if there are too many literary prizes.

Robert B. Parker, best known for a series of novels starring Boston private eye Spenser, has died at 77. Sarah Weinman has quickly gathered an excellent list of relevant links. . . . M.A. Orthofer reacts to the recent and widely-linked-to Wall Street Journal piece about the “death of the slush pile.” . . . How would you like to be a famous author in the early 20th century named Winston Churchill? Bummer. . . . Book Patrol unearths a book about the sex lives of Civil War soldiers, a side of their lives “that they and their families tried to hide from posterity and Ken Burns.” . . . In 1967, Leonard Woolf was sounding a pre-Hitchens note. . . . I’ve been meaning to see An Education for a long time now. After reading Maud Newton’s description, I’d also like to read the book on which it was based. . . . Blake Morrison on the art of the first sentence. (Via Books, Inq.) . . . Illustrations from French children’s books, 1900-1949. (Via Bookslut) . . . Garth Risk Hallberg wonders if there are too many literary prizes.

Tuesday, January 19th, 2010

In April, famed science writer Edward O. Wilson will publish his first novel, Anthill

In April, famed science writer Edward O. Wilson will publish his first novel, Anthill . There’s an excerpt of the novel in this week’s issue of The New Yorker. The magazine’s fiction editor, Deborah Treisman, interviewed Wilson about the project, which includes “ a novella within the novel, which is told entirely from the point of view of ants.”

. There’s an excerpt of the novel in this week’s issue of The New Yorker. The magazine’s fiction editor, Deborah Treisman, interviewed Wilson about the project, which includes “ a novella within the novel, which is told entirely from the point of view of ants.”

I tried to develop the full picture, a fuller picture of the whole ecosystem—that is, exactly what is there—and then center the action on a group of ant colonies. Which might sound as though I’m descending into the trivial, but in fact what I’ve done is take the reader into the most advanced social system that exists on Earth outside of human beings, and describe life within an ant colony. [. . .] And I can do that because I’ve spent much of a career working on how ants communicate, how they learn, what they know, how they orient, and so on. And it’s as though I were describing, I think many will see, as though I were describing in that novella—as you say correctly, it takes about a quarter of the book—as though I were describing accurately how life might have evolved up to a high social level on another planet.

Saturday, January 16th, 2010

Miles Corwin has a very good piece in Columbia Journalism Review about how Gabriel García Márquez’s career as a newspaper reporter influenced the later work that would make him world-famous. A piece:

Miles Corwin has a very good piece in Columbia Journalism Review about how Gabriel García Márquez’s career as a newspaper reporter influenced the later work that would make him world-famous. A piece:

In 1955, eight crew members of a Colombian naval destroyer in the Caribbean were swept overboard by a giant wave. Luis Alejandro Velasco, a sailor who spent ten days on a life raft without food or water, was the only survivor. The editor of the Colombian newspaper El Espectador assigned the story to a twenty-seven-year-old reporter who had been dabbling in fiction and had a reputation as a gifted feature writer: Gabriel García Márquez.

The young journalist quickly uncovered a military scandal. As his fourteen-part series revealed, the sailors owed their deaths not to a storm, as Colombia’s military dictatorship had claimed, but to naval negligence. [. . .] By the time the series ended, El Espectador’s circulation had almost doubled. The public always likes an exposé, but what made the stories so popular was not simply the explosive revelations of military incompetence. García Márquez had managed to transform Velasco’s account into a narrative so dramatic and compelling that readers lined up in front of the newspaper’s offices, waiting to buy copies.

I strongly suggest reading the whole thing.

(Via The Browser)

Friday, January 15th, 2010

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

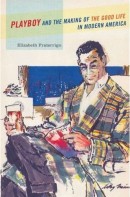

Tom Bissell writes a terrific review of Playboy and the Making of the Good Life in Modern America by Elizabeth Fraterrigo, a book he calls dry but careful and wide-ranging: “Fraterrigo has given us the most laudably sober and analytically rigorous book ever written about an adult magazine. While her prose strays into occasional thesisese, her research is phenomenally thorough and her conclusions are bold enough to be interesting and modest enough to be feasible.” . . . Leo Robson elegantly recommends Frank Kermode’s new book about E.M. Forster. . . . Christopher Hitchens admires the work of J.G. Ballard, “our great specialist in catastrophe.” . . . Jad Adams assesses a new biography of Thomas de Quincey, “the first – and still the finest – literary dope fiend.” . . . David Ulin says that Robert Stone’s new collection of stories “may not represent a complete return to form, but it’s far more satisfying” than his previous two books and “brilliant in places.” . . . Jessica Loudis believes that Louis Menand’s The Marketplace of Ideas “should be required reading for anybody considering a PhD in the humanities.”

Tom Bissell writes a terrific review of Playboy and the Making of the Good Life in Modern America by Elizabeth Fraterrigo, a book he calls dry but careful and wide-ranging: “Fraterrigo has given us the most laudably sober and analytically rigorous book ever written about an adult magazine. While her prose strays into occasional thesisese, her research is phenomenally thorough and her conclusions are bold enough to be interesting and modest enough to be feasible.” . . . Leo Robson elegantly recommends Frank Kermode’s new book about E.M. Forster. . . . Christopher Hitchens admires the work of J.G. Ballard, “our great specialist in catastrophe.” . . . Jad Adams assesses a new biography of Thomas de Quincey, “the first – and still the finest – literary dope fiend.” . . . David Ulin says that Robert Stone’s new collection of stories “may not represent a complete return to form, but it’s far more satisfying” than his previous two books and “brilliant in places.” . . . Jessica Loudis believes that Louis Menand’s The Marketplace of Ideas “should be required reading for anybody considering a PhD in the humanities.”

Friday, January 15th, 2010

In the latest issue of The Believer, Chris Bachelder has a brief but potent piece about how “the vivid surprises of child-rearing seem so similar to the vivid surprises of good literature.” A taste:

One of my daughter’s favorite books is called Neighborhood Animals. I wish the book had a counter in it, like a website, so that I could see how many hundreds of times we’ve read it. I know this book. Certainly it must be among the least surprising objects in my home. When my daughter chooses Neighborhood Animals, I have the impulse to flee the house and check into a rental cabin under an assumed name. I mention this simply so that you will not presume that I am at all vigilant or attuned. I am no sensitive instrument of detection. . . . One Saturday morning a few weeks ago my daughter brought me Neighborhood Animals, and she opened it to the first page (“Is that a dog in the park?”). My pulse slowed to hibernatory rate and I struggled to remain conscious. “A dog has an amazing sense of smell,” I mumbled. “It can tell what people and dogs have been here even after they’re gone.” My daughter sat up straight, held her hand on the page so that I could not turn it. She faced me, her wide eyes filled with a question I wasn’t equipped to answer.

(Via Chip Brantley)

Thursday, January 14th, 2010

The Caustic Cover Critic’s hilarious series of posts about Tutis, a publisher that takes public-domain works and puts ridiculously inappropriate covers on them. Lots of laughs. . . . Daily Design Discoveries has a slide show of a prettier bunch. . . . Elvis would have been 75 last week. To mark the anniversary, John Gall posts a whole mess of book covers featuring The King, including Invasion of the Elvis Zombies. . . . Sadly, the Book Design Review has gone on “indefinite hiatus.” A good excuse to look through its archives. . . . A ship that had been “carrying affordable books to ports throughout the world” since 1978 has been grounded by a new law. . . . Peter Ginna, now at Bloomsbury Press, once received a manuscript along with a pair of shoes he had ordered from Land’s End. . . . Surely, we can’t do worse than Android Karenina, so now this nonsense can stop, right? Right?

The Caustic Cover Critic’s hilarious series of posts about Tutis, a publisher that takes public-domain works and puts ridiculously inappropriate covers on them. Lots of laughs. . . . Daily Design Discoveries has a slide show of a prettier bunch. . . . Elvis would have been 75 last week. To mark the anniversary, John Gall posts a whole mess of book covers featuring The King, including Invasion of the Elvis Zombies. . . . Sadly, the Book Design Review has gone on “indefinite hiatus.” A good excuse to look through its archives. . . . A ship that had been “carrying affordable books to ports throughout the world” since 1978 has been grounded by a new law. . . . Peter Ginna, now at Bloomsbury Press, once received a manuscript along with a pair of shoes he had ordered from Land’s End. . . . Surely, we can’t do worse than Android Karenina, so now this nonsense can stop, right? Right?

Wednesday, January 13th, 2010

From American Pastoral

From American Pastoral by Philip Roth:

by Philip Roth:

You fight your superficiality, your shallowness, so as to try to come at people without unreal expectations, without an overload of bias or hope or arrogance, as untanklike as you can be, sans cannon and machine guns and steel plating half a foot thick; you come at them unmenacingly on your own ten toes instead of tearing up the turf with your caterpillar treads, take them on with an open mind, as equals, man to man, as we used to say, and yet you never fail to get them wrong. You might as well have the brain of a tank. You get them wrong before you meet them, while you’re anticipating meeting them; you get them wrong while you’re with them; and then you go home to tell somebody else about the meeting and you get them all wrong again. Since the same generally goes for them with you, the whole thing is really a dazzling illusion empty of all perception, an astonishing farce of misperception. And yet what are we to do about this terribly significant business of other people, which gets bled of the significance we think it has and takes on instead a significance that is ludicrous, so ill-equipped are we all to envision one another’s interior workings and invisible aims? Is everyone to go off and lock the door and sit secluded like the lonely writers do, in a soundproof cell, summoning people out of words and then proposing that these word people are closer to the real thing than the real people that we mangle with our ignorance every day? The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, on careful reconsideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong. Maybe the best thing would be to forget being right or wrong about people and just go along for the ride. But if you can do that—well, lucky you.

Tuesday, January 12th, 2010

I was hoping to be named a judge for this year’s Tournament of Books over at The Morning News. Alas. I’ll have to enjoy the fun through the window, as I do every year. The shortlist of books has been announced, along with this year’s judges, a stellar crew.

I was hoping to be named a judge for this year’s Tournament of Books over at The Morning News. Alas. I’ll have to enjoy the fun through the window, as I do every year. The shortlist of books has been announced, along with this year’s judges, a stellar crew.

For those of you who don’t know, the ToB chooses 16 of the previous year’s best novels, sets up a bracket like the NCAA basketball tournament, and stops only when one book is left standing. This is the sixth installment of the tourney, which kicks off in March. Last year’s winner was A Mercy by Toni Morrison. Winners before that were The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Díaz, The Road by Cormac McCarthy, The Accidental by Ali Smith, and Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell.

For this year, I’m going to make the safe prediction that Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel will take home the Rooster (the tournament’s prize).

Tuesday, January 12th, 2010

Eric Rohmer, the legendary French filmmaker who died at 89 on Monday, was a writer before he got into movies. In addition to writing a novel (Elisabeth) under the pseudonym Gilbert Cordier, he wrote six stories that would later be turned into his famous series of films, Six Moral Tales.

Eric Rohmer, the legendary French filmmaker who died at 89 on Monday, was a writer before he got into movies. In addition to writing a novel (Elisabeth) under the pseudonym Gilbert Cordier, he wrote six stories that would later be turned into his famous series of films, Six Moral Tales.

The box set of those six DVDs comes with a book of the original stories, which Rohmer says were written “when I did not yet know whether I was going to be a filmmaker.” The most famous of those movies at the time in the U.S. (nominated for two Oscars) may have been My Night at Maud’s. (The original trailer for it can be seen here.) Early on in the original story, the narrator writes:

I was living in Clermont-Ferrand, an industrial city in south-central France, where for two months I had been working as an engineer at the Michelin tire complex. Prior to that, I had worked for a subsidiary of Standard Oil in Vancouver, before moving on to Valparaíso. Not that I had ever considered myself an expatriot. An involvement that I won’t go into had kept me away from France longer than I had intended. Now I was free, and beginning to think about marriage.

Monday, January 11th, 2010

I think we can all agree that it’s never too early in the week to share some gems from the Twitter stream of personal ads from the London Review of Books:

By placing this ad I’ve lowered my expectations considerably. Now even you’re in with a chance. Don’t blow it by mentioning your mum. F, 46.

My animal passions would satisfy any F but for the filibustering of this damned colon. Write to M, 83, for list of approved solids.

I’ve created an Excel spreadsheet to document all the lovers I’ve had in my life. I’d like you to be cell A2. IT consultant (M, 34).

Respondents to my last ad: this time meet the real me. Now alcohol-free, medicated, and wearing trousers. M, 41.

Monday, January 11th, 2010

For a while, I’ve been hearing about the New Republic’s imminent foray into online book criticism. The site, simply titled The Book, has now launched. Executive editor Isaac Chotiner explains its ambitious aims in an introductory letter. The Book has been added to the LInks page, and I’m sure to be sending you over there with some frequency.

Friday, January 8th, 2010

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Ah, goodbye, year-end lists; hello again, substantial reviews. A strong initial batch for 2010: If you read one thing today, make it James Salter’s mesmerizing review of William Langewiesche’s book about “the Miracle on the Hudson.” . . . Mary Midgley expertly summarizes the appeal of a new book about the brain’s hemispheres. . . . Provocative defenses of the suburbs are, in my opinion, all too rare. Here’s one now: “The publisher’s blurb introduces The Freedoms of Suburbia, Paul Barker’s enchanting and persuasive pictorial essay, with a nervous defiance as if the book were proposing free heroin for toddlers.” . . . Dwight Garner says we’ll be reading books about the current financial crisis for decades, but “[f]ew if any of these books will be as pleasurable — and by that I mean as literate or as wickedly funny — as John Lanchester’s I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay.” . . . Michael Agger reviews You Are Not a Gadget, tech guru Jaron Lanier’s manifesto/lament about what the Web has become: “Lanier, to his credit, is not a simple pessimist. [...] But his critique is ultimately just a particular brand of snobbery.” . . . David Yaffe calls a new biography of Thelonious Monk “exhaustive, necessary and, as of now, definitive.” . . . Adam Shatz reviews the work of Orhan Pamuk, “who writes in the Esperanto of international literary fiction.” . . . Justin Taylor reviews The Book of Jokes by Momus, with a twist. The Believer asked him to review it anonymously—not Taylor; the book: “[S]oon enough a book arrived at my house. Its covers, front matter, and endpages had all been stripped, and the spine blacked out with a Sharpie. I didn’t know what it was called or who wrote it or who was publishing it or when. I didn’t know if it was the author’s first or twenty-first publication.”

Ah, goodbye, year-end lists; hello again, substantial reviews. A strong initial batch for 2010: If you read one thing today, make it James Salter’s mesmerizing review of William Langewiesche’s book about “the Miracle on the Hudson.” . . . Mary Midgley expertly summarizes the appeal of a new book about the brain’s hemispheres. . . . Provocative defenses of the suburbs are, in my opinion, all too rare. Here’s one now: “The publisher’s blurb introduces The Freedoms of Suburbia, Paul Barker’s enchanting and persuasive pictorial essay, with a nervous defiance as if the book were proposing free heroin for toddlers.” . . . Dwight Garner says we’ll be reading books about the current financial crisis for decades, but “[f]ew if any of these books will be as pleasurable — and by that I mean as literate or as wickedly funny — as John Lanchester’s I.O.U.: Why Everyone Owes Everyone and No One Can Pay.” . . . Michael Agger reviews You Are Not a Gadget, tech guru Jaron Lanier’s manifesto/lament about what the Web has become: “Lanier, to his credit, is not a simple pessimist. [...] But his critique is ultimately just a particular brand of snobbery.” . . . David Yaffe calls a new biography of Thelonious Monk “exhaustive, necessary and, as of now, definitive.” . . . Adam Shatz reviews the work of Orhan Pamuk, “who writes in the Esperanto of international literary fiction.” . . . Justin Taylor reviews The Book of Jokes by Momus, with a twist. The Believer asked him to review it anonymously—not Taylor; the book: “[S]oon enough a book arrived at my house. Its covers, front matter, and endpages had all been stripped, and the spine blacked out with a Sharpie. I didn’t know what it was called or who wrote it or who was publishing it or when. I didn’t know if it was the author’s first or twenty-first publication.”

Thursday, January 7th, 2010

Thanks to The Morning News, I’ve just discovered Curious Pages: Recommended inappropriate books for kids. At the bottom of the home page is this disclaimer:

Thanks to The Morning News, I’ve just discovered Curious Pages: Recommended inappropriate books for kids. At the bottom of the home page is this disclaimer:

Looking for books about teddy bears or rainbows or feelings? You’re at the wrong place. Here we celebrate the offbeat, the abstract, the unusual, the surreal, the macabre, the inappropriate, the subversive and the funky.

But the site is a lot more welcoming than that makes it sound. And the gems it has found are something special, like One Thousand Christmas Beards by Roger Duvoisin (1955), in which Santa Claus goes on a spree to rip the beard off anyone impersonating him. Sample text:

There were more, many more false Santas!

When Santa had pulled all their false beards,

and frightened them all into hiding,

he was ready to ride back home.

Santa stomps a dude when he has to.

Also over the holiday, the site put together a fantastically charming collection of wintry images from children’s books. Enjoy.

Thursday, January 7th, 2010

Shalom Auslander, author of the very funny, caustic memoir Foreskin’s Lament

Shalom Auslander, author of the very funny, caustic memoir Foreskin’s Lament , is writing a “comic novel about genocide.” You read that right. And he’s blogging about the project. I’m not sure he convinces me how he’s going to make it funny, but there’s something cathartic in the purity of his poison, as in this section, which concerns a seven-year-old bully named Brian who’s been bullying Auslander’s four-year-old son:

, is writing a “comic novel about genocide.” You read that right. And he’s blogging about the project. I’m not sure he convinces me how he’s going to make it funny, but there’s something cathartic in the purity of his poison, as in this section, which concerns a seven-year-old bully named Brian who’s been bullying Auslander’s four-year-old son:

I look at Brian—almost half my height and damn near double my weight, his barely-fitting XL “Transformers” t-shirt covered with bits of cake and ice cream, his fat little legs already starting to splay out in the manner of the morbidly obese, the cursed beams of his insufficient structure already too weak to cope with the oversized load they are being asked to support, his hollow, heavy-lidded eyes blinking out at the world in the sort of dumb, mouth-breathing incomprehension you see in mall kids and SS men and Glenn Beck—and I think about the genocide books I’ve been reading. They all wonder why. They all seem to think there’s a reason, and that if they can identify that reason, these horrible crimes will never happen again. The reason, they say, is poverty. The reason is racism, the West, the East, religion, atheism, capitalism, communism. But it isn’t.

The reason is Brian.

There is no reason for Brian. I’d like there to be. But there isn’t. Brian just is. Brian happens. Is Brian going to lead Hutus to slaughter Tutsis? I don’t know. Perhaps he’s not that ambitious. But if Brian were a Hutu, Brian would hack a Tutsi, no question about it. Brian would hack a lot of Tutsis. Brian would be the Hutu in that news footage, dancing around the mangled corpse of a young Tutsi with his bloody machete raised triumphantly overhead. Only fatter. And eating a Twinkie.

(Via Mark Athitakis)

Wednesday, January 6th, 2010

Chad Post at Three Percent has announced the longlist of 25 nominees for the third annual Best Translated Book Award. Starting Monday, Post and his colleagues will feature one of the books selected every day leading up to February 16, when the short list of finalists will be announced.

Chad Post at Three Percent has announced the longlist of 25 nominees for the third annual Best Translated Book Award. Starting Monday, Post and his colleagues will feature one of the books selected every day leading up to February 16, when the short list of finalists will be announced.

Three Percent is the blog arm of Open Letter Books, which was profiled in the New York Times over the holidays.

Wednesday, January 6th, 2010

From In Praise of Idleness

From In Praise of Idleness by Bertrand Russell:

by Bertrand Russell:

Like most of my generation, I was brought up on the saying: ‘Satan finds some mischief still for idle hands to do.’ Being a highly virtuous child, I believed all that I was told, and acquired a conscience which has kept me working hard down to the present moment. But although my conscience has controlled my actions, my opinions have undergone a revolution. I think that there is far too much work done in the world, that immense harm is caused by the belief that work is virtuous, and that what needs to be preached in modern industrial countries is quite different from what always has been preached. Everyone knows the story of the traveller in Naples who saw twelve beggars lying in the sun (it was before the days of Mussolini), and offered a lira to the laziest of them. Eleven of them jumped up to claim it, so he gave it to the twelfth. This traveller was on the right lines. But in countries which do not enjoy Mediterranean sunshine idleness is more difficult, and a great public propaganda will be required to inaugurate it. I hope that, after reading the following pages, the leaders of the YMCA will start a campaign to induce good young men to do nothing. If so, I shall not have lived in vain.

Tuesday, January 5th, 2010

In considering Katie Roiphe’s recent essay about how young male American writers have “repudiated the aggressive virility of their predecessors,” Mark Athitakis offers several sharp points, and wonders what Roiphe would make of Richard Ford’s Frank Bascombe, one of many characters who complicate the picture. . . . Speaking of aggressive virility, in his soon-to-be-published book about Warren Beatty, Peter Biskind estimates how many women the leading man has taken to bed. Even assuming a generous margin of error, it’s a startling number. . . . James Mustich starts 2010 eagerly awaiting 20 books. . . . The Millions also previews the year in books. . . . And Chad Post of Open Letter points to compelling translations being published in the next three months. . . . James Morrison (aka the Caustic Cover Critic) starts the year “with some sleaze.” . . . In soliciting choices for hated books, Joseph Sullivan says of his: “When done, I immediately went out and bought two hamsters and a cage so that something could rip that book apart and pee on it.” . . . The site Odd Books is updated far too infrequently for my taste, but it’s always worth the wait.

In considering Katie Roiphe’s recent essay about how young male American writers have “repudiated the aggressive virility of their predecessors,” Mark Athitakis offers several sharp points, and wonders what Roiphe would make of Richard Ford’s Frank Bascombe, one of many characters who complicate the picture. . . . Speaking of aggressive virility, in his soon-to-be-published book about Warren Beatty, Peter Biskind estimates how many women the leading man has taken to bed. Even assuming a generous margin of error, it’s a startling number. . . . James Mustich starts 2010 eagerly awaiting 20 books. . . . The Millions also previews the year in books. . . . And Chad Post of Open Letter points to compelling translations being published in the next three months. . . . James Morrison (aka the Caustic Cover Critic) starts the year “with some sleaze.” . . . In soliciting choices for hated books, Joseph Sullivan says of his: “When done, I immediately went out and bought two hamsters and a cage so that something could rip that book apart and pee on it.” . . . The site Odd Books is updated far too infrequently for my taste, but it’s always worth the wait.

Tuesday, January 5th, 2010

Hilary Mantel writes about what Cinderella’s life may have been like after 20 years of marriage. This spurs Maud Newton to link to an old Carol Burnett sketch about an aging Snow White. And not-entirely-unrelated, news of a possible Wizard of Oz sequel about Dorothy’s granddaughter, potentially written by Todd McFarlane, famous for comic books, action figures, and video games, who said a few years ago: “My pitch was ‘How do we get people who went to Lord of the Rings to embrace this?’ I want to create [an interpretation] that has a 2007 ‘wow’ factor.” Yes, how could you possibly get people to embrace The Wizard of Oz? I wish we could make a culture-wide resolution in 2010 to leave the sacred past alone — no Dorothy descendant inspired by Lara Croft, no Great Expectations “rewritten” to make Pip a zombie, vampire, or avatar. Just to see how it feels to go a whole year with dignity.

Tuesday, January 5th, 2010

Lord Shaftesbury on Sir John Seeley’s Ecce Homo (1865), which examined the evidence for the truth of the Gospels:

. . . the most pestilential book ever vomited, I think, from the jaws of hell.

Tuesday, January 5th, 2010

Open Letters has started the year with a striking redesign and a bigger tent. The new January issue shows off the new look and includes a review of a new history of the Vikings (not the football team).

The site has also brought under its aegis three worthwhile blogs: Lisa Peet’s Like Fire, Steve Donoghue’s Stevereads, and a daily dose of Walt Whitman. Best wishes to all of them at their new, renovated home.

Garry Kasparov reviews a book about chess and artificial intelligence, a springboard for his thoughts about the state of the game and technology. Fascinating. . . . Matt Ridley reviews a “witty and incisive” book about the “quest to end aging.” . . . Alice Kaplan writes a wonderfully brainy-but-breezy essay about “volumes assessing literary reputations during the years of the Nazi occupation of France.” . . . Richard Posner writes a long, characteristically intelligent piece about the history of miscegenation laws in the U.S. (“People take pride in being descended from Mayflower passengers, or from Revolutionary War veterans, though after a very few generations the traits that distinguished an honored ancestor, even if genetic, disappears in the genetic reshuffling that occurs in every new generation.”) . . . The Economist judges that Peter Carey’s latest novel, a fictional retelling of Tocqueville’s travels in America, “has all the quirky qualities that we have come to expect from Peter Carey: a winding narrative, a mass of vivid historical detail, and some very lively writing.” . . . The Guardian calls Jon McGregor’s new novel, Even the Dogs, “a [powerful] fragmentary group portrait” of addicts and vagrants who move in and out of an empty flat over several years. . . . Jeff VanderMeer calls a new novel about Depression-era bank robbers “a rip-roaring yarn that manages to be both phantasmagorical and historically accurate. In its labyrinthine, luminous narrative, reminiscent of Michael Chabon’s best fiction, readers will find powerful parallels to the present-day.”

Garry Kasparov reviews a book about chess and artificial intelligence, a springboard for his thoughts about the state of the game and technology. Fascinating. . . . Matt Ridley reviews a “witty and incisive” book about the “quest to end aging.” . . . Alice Kaplan writes a wonderfully brainy-but-breezy essay about “volumes assessing literary reputations during the years of the Nazi occupation of France.” . . . Richard Posner writes a long, characteristically intelligent piece about the history of miscegenation laws in the U.S. (“People take pride in being descended from Mayflower passengers, or from Revolutionary War veterans, though after a very few generations the traits that distinguished an honored ancestor, even if genetic, disappears in the genetic reshuffling that occurs in every new generation.”) . . . The Economist judges that Peter Carey’s latest novel, a fictional retelling of Tocqueville’s travels in America, “has all the quirky qualities that we have come to expect from Peter Carey: a winding narrative, a mass of vivid historical detail, and some very lively writing.” . . . The Guardian calls Jon McGregor’s new novel, Even the Dogs, “a [powerful] fragmentary group portrait” of addicts and vagrants who move in and out of an empty flat over several years. . . . Jeff VanderMeer calls a new novel about Depression-era bank robbers “a rip-roaring yarn that manages to be both phantasmagorical and historically accurate. In its labyrinthine, luminous narrative, reminiscent of Michael Chabon’s best fiction, readers will find powerful parallels to the present-day.”

From This Was Racing by Joe H. Palmer (1953), the subject of the next Backlist feature, which will be published in the near future:

From This Was Racing by Joe H. Palmer (1953), the subject of the next Backlist feature, which will be published in the near future: If you haven’t bookmarked the site

If you haven’t bookmarked the site  Peter Lopatin says that Rebecca Newberger Goldstein’s 36 Arguments for the Existence of God is

Peter Lopatin says that Rebecca Newberger Goldstein’s 36 Arguments for the Existence of God is  Judith Gurewich, Publisher of Other Press, writes about

Judith Gurewich, Publisher of Other Press, writes about  One of my 2010 reading resolutions (success rate of such resolutions: approximately 27%), which I’ve mentioned before and won’t again until and unless I fulfill it (I promise), is to read Robert Walser. Over at Two Words, Scott Esposito

One of my 2010 reading resolutions (success rate of such resolutions: approximately 27%), which I’ve mentioned before and won’t again until and unless I fulfill it (I promise), is to read Robert Walser. Over at Two Words, Scott Esposito  Robert B. Parker, best known for a series of novels starring Boston private eye Spenser, has died at 77. Sarah Weinman has quickly

Robert B. Parker, best known for a series of novels starring Boston private eye Spenser, has died at 77. Sarah Weinman has quickly  In April, famed science writer Edward O. Wilson will publish his first novel,

In April, famed science writer Edward O. Wilson will publish his first novel,  Miles Corwin has

Miles Corwin has  Tom Bissell

Tom Bissell  The Caustic Cover Critic’s

The Caustic Cover Critic’s  From

From  I was hoping to be named a judge for this year’s Tournament of Books over at The Morning News. Alas. I’ll have to enjoy the fun through the window, as I do every year. The shortlist of books

I was hoping to be named a judge for this year’s Tournament of Books over at The Morning News. Alas. I’ll have to enjoy the fun through the window, as I do every year. The shortlist of books  Eric Rohmer, the legendary French filmmaker who

Eric Rohmer, the legendary French filmmaker who  Ah, goodbye, year-end lists; hello again, substantial reviews. A strong initial batch for 2010: If you read one thing today, make it James Salter’s

Ah, goodbye, year-end lists; hello again, substantial reviews. A strong initial batch for 2010: If you read one thing today, make it James Salter’s  Thanks to

Thanks to  Shalom Auslander, author of the very funny, caustic memoir

Shalom Auslander, author of the very funny, caustic memoir  Chad Post at Three Percent has

Chad Post at Three Percent has  From

From  In considering

In considering