Frances Evangelista, who blogs at Nonsuch Book, is devoting August to reading (and blogging about) all 42 entries in Melville House’s Art of the Novella series. A little less than midway through the month, she’s a bit behind pace, having completed 15 of the books. But it still seems possible she will complete the goal, which would be impressive. Melville House joined in the fun by challenging other readers to join Evangelista and compete for prizes throughout the month. The interested are urged to join at nine levels, including Curious (one novella), Passionate (nine novellas), and Fanatical (27 novellas).

Frances Evangelista, who blogs at Nonsuch Book, is devoting August to reading (and blogging about) all 42 entries in Melville House’s Art of the Novella series. A little less than midway through the month, she’s a bit behind pace, having completed 15 of the books. But it still seems possible she will complete the goal, which would be impressive. Melville House joined in the fun by challenging other readers to join Evangelista and compete for prizes throughout the month. The interested are urged to join at nine levels, including Curious (one novella), Passionate (nine novellas), and Fanatical (27 novellas).

Between other reading plans and additional scheduling conflicts, I’m only safely in on the Curious level. Last week, I read Lucinella by Lore Segal. It was originally published in 1976, and is actually part of Melville House’s “contemporary” Art of the Novella series. Whether this qualifies to satisfy my Curious requirement, I don’t know. Life can be confusing.

by Lore Segal. It was originally published in 1976, and is actually part of Melville House’s “contemporary” Art of the Novella series. Whether this qualifies to satisfy my Curious requirement, I don’t know. Life can be confusing.

Lucinella is very funny. It opens at Yaddo, the artists’ colony, where the eponymous narrator describes her fellow guests, “five poets, four men, one woman, and an obese dog called Winifred.” (An early instance of Segal’s sense of humor: “Because Winifred is a real dog I have changed his sex to protect his privacy.”) The book follows the group at Yaddo, and then to New York City, as they fret about reviews, fight over poetic strategies, and fall into various cocktail parties and beds. It is, in short, a satire of the writing life.

It’s full of pithy descriptions (“She’s forty, five foot by four by four, and a genuine Russian.”), well-orchestrated group scenes, and modest, sometimes faintly dated experimentation. It builds to a conclusion that I found quite moving. And it contains the exchange below, which is now one of my all-time favorites. Lucinella has been haranguing her boyfriend William for his habits, which keep her from ever keeping the house in order (”William, how come you do everything wrong all the time?”). We pick it up from there:

“William? How come you never nag me?”

“What about?” asks William.

“Whatever you can’t stand about me.”

William is thinking. “When you keep nagging I sometimes want to murder you, but I can stand it.”

“Why don’t you tell me to straighten out my towel on the rack?”

“Because I don’t care if it’s scrumpled.”

“But, William, a scrumpled towel cannot dry!”

“Lucinella, sweetheart, love! A dry towel does not move my imagination!”

“Nag me. Go on,” I say.

William looks harried. “You’re a slob,” he says.

“No, I mean something true about me. Go on.”

“You are a true slob,” William says.

“A slob, William! I! Who can neither eat nor write nor love so long as my house is not in perfect order, how am I a slob?”

“Your towel is scrumpled in the bathroom. Lucinella, I don’t care—”

“Ah, but,” I say, “that’s different, don’t you see, that’s only because I haven’t got around yet to straightening it out. Nag me some more.”

“The kitchen,” says William, “is in such a shambles we have to eat out.”

“Only till I find the right Contact paper,” I explain, “which they no longer manufacture. Go on.”

At Kirkus,

At Kirkus,  Philip Larkin wrote the following letter to his friend Norman Iles, who he had met when they were students together at Oxford, on Feb. 26, 1967:

Philip Larkin wrote the following letter to his friend Norman Iles, who he had met when they were students together at Oxford, on Feb. 26, 1967: Jonathan Franzen recently suggested that David Foster Wallace made things up in some of his most famous nonfiction pieces, including

Jonathan Franzen recently suggested that David Foster Wallace made things up in some of his most famous nonfiction pieces, including  The letter below was written by Stendhal to his sister Pauline on Oct. 29, 1808:

The letter below was written by Stendhal to his sister Pauline on Oct. 29, 1808: This week, the blog is featuring writers’ correspondence. The letter below was written by Eudora Welty to William Maxwell and his wife Emily in May 1963. It’s featured in

This week, the blog is featuring writers’ correspondence. The letter below was written by Eudora Welty to William Maxwell and his wife Emily in May 1963. It’s featured in  Each day this week, the blog will feature two letters. The one below was written by Harold Ross, the founder and editor of The New Yorker, to Orson Welles on Jan. 31, 1945. A selection of Ross’ correspondence was published as

Each day this week, the blog will feature two letters. The one below was written by Harold Ross, the founder and editor of The New Yorker, to Orson Welles on Jan. 31, 1945. A selection of Ross’ correspondence was published as  Each day this week, the blog will feature two letters. The one below was written by Anton Chekhov to publishing magnate Alexei Suvorin, his close friend, on Sept. 8, 1891:

Each day this week, the blog will feature two letters. The one below was written by Anton Chekhov to publishing magnate Alexei Suvorin, his close friend, on Sept. 8, 1891: Cultural critic and Second Pass contributor Lisa Levy has launched the site

Cultural critic and Second Pass contributor Lisa Levy has launched the site  Emma Brockes’

Emma Brockes’  Tom Bissell writes

Tom Bissell writes  At the New York Observer,

At the New York Observer,  Nearly a decade ago, James Gavin published

Nearly a decade ago, James Gavin published  Oct. 5 marks the centenary of the birth of Irish novelist Flann O’Brien — the most famous pen name of those used by Brian O’Nolan — who died of cancer at age 54. Keith Hopper recently wrote an appreciation of O’Brien and his work

Oct. 5 marks the centenary of the birth of Irish novelist Flann O’Brien — the most famous pen name of those used by Brian O’Nolan — who died of cancer at age 54. Keith Hopper recently wrote an appreciation of O’Brien and his work  After his prize-winning Stuart: A Life Backwards, Alexander Masters’ follow-up is another book in which the author “[finds] himself unexpectedly intimate with an unusual person” — this time, his landlord, a shut-in former mathematics prodigy.

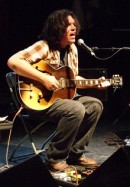

After his prize-winning Stuart: A Life Backwards, Alexander Masters’ follow-up is another book in which the author “[finds] himself unexpectedly intimate with an unusual person” — this time, his landlord, a shut-in former mathematics prodigy.  This is only tangentially books-related, but I don’t care, because I’m a big fan of Richard Buckner. In a two-part interview —

This is only tangentially books-related, but I don’t care, because I’m a big fan of Richard Buckner. In a two-part interview —  Frances Evangelista, who blogs at

Frances Evangelista, who blogs at  September marks the centenary of William Golding’s birth. I’ve only read Lord of the Flies, and so long ago that it only survives in my memory as a punchline for chaotic situations. (And I wouldn’t even have to have read it to know that.) Golding’s British publisher has reissued Flies, which was his first novel, and The Inheritors, his second. John Self

September marks the centenary of William Golding’s birth. I’ve only read Lord of the Flies, and so long ago that it only survives in my memory as a punchline for chaotic situations. (And I wouldn’t even have to have read it to know that.) Golding’s British publisher has reissued Flies, which was his first novel, and The Inheritors, his second. John Self  Woody Haut says that “Richard Hallas’ You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up remains one of the most evocative and subversive novels of its time,”

Woody Haut says that “Richard Hallas’ You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up remains one of the most evocative and subversive novels of its time,”  In my first review for the New York Times,

In my first review for the New York Times,  David Gee shares

David Gee shares  Last weekend marked the 60th anniversary of the publication of The Catcher in the Rye, and to commemorate the event, the Fiction Advocate published “The Real Holden Caulfield,” an extended essay by Michael Moats. The whole thing is available for $1.99

Last weekend marked the 60th anniversary of the publication of The Catcher in the Rye, and to commemorate the event, the Fiction Advocate published “The Real Holden Caulfield,” an extended essay by Michael Moats. The whole thing is available for $1.99  From

From  Any review titled “Bullshit Heaven” has to have something going for it. Jed Perl has

Any review titled “Bullshit Heaven” has to have something going for it. Jed Perl has  The July issue of Harper’s features an excerpt from

The July issue of Harper’s features an excerpt from  After completing a brief stretch of true-crime reading last year, I tried to find lists of other recommendations. A lot of books in the genre get suggested over and over again. But Peter Manso

After completing a brief stretch of true-crime reading last year, I tried to find lists of other recommendations. A lot of books in the genre get suggested over and over again. But Peter Manso  Today is a good day for baseball geeks like me, as it marks the publication of Craig Robinson’s

Today is a good day for baseball geeks like me, as it marks the publication of Craig Robinson’s  Rahul Jacob reviews

Rahul Jacob reviews  On Monday, July 11, I’ll have the distinct pleasure of appearing at Greenlight Bookstore in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene neighborhood for the store’s Blogger/Author Pairings series. I’ll be speaking with Carmela Ciuraru, whose book,

On Monday, July 11, I’ll have the distinct pleasure of appearing at Greenlight Bookstore in Brooklyn’s Fort Greene neighborhood for the store’s Blogger/Author Pairings series. I’ll be speaking with Carmela Ciuraru, whose book,  A.S. Hamrah

A.S. Hamrah