Last year, I pointed to an essay about the work of Gilbert Rogin, who wrote comic fiction that was praised by John Updike and John Cheever, among others. Now, his two novels are being republished

Last year, I pointed to an essay about the work of Gilbert Rogin, who wrote comic fiction that was praised by John Updike and John Cheever, among others. Now, his two novels are being republished, and the New York Observer has an entertaining profile of him: “[I]n the spring of 1980, Mr. Rogin, 50 years old and seemingly at the top of his game, submitted a new short story to Roger Angell, the baseball essayist who was then chief fiction editor at The New Yorker. Mr. Angell passed, telling Mr. Rogin, ‘You’re repeating yourself.’ [. . .] That Mr. Rogin took Mr. Angell’s criticism personally should come as no surprise. Told that the Russians were boycotting the 1984 Olympics, Mr. Rogin carped, ‘Why are they doing this to me?’ ” . . . Ian Crouch takes a look at Ladbrokes’ odds for this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature. William Trevor sits at 45-1. Trevor is 82 years old. I hope he has many years left to win the award, but one never knows. I don’t care about awards, generally, but if Trevor never wins it I’ll be kind of ticked off. . . . After a time of rough sailing, Harper’s is showing signs of renewed life. The magazine has hired Zadie Smith to write its monthly New Books column. (She replaces the very good Ben Moser, who will continue writing for Harper’s.) . . . Gay Talese sits down for a substantive interview with James Mustich. . . . On October 5 in Park Slope, as part of the lecture series Adult Education, Jim Hanas will celebrate the release of his short story collection, and various presenters will speak about “The Future of the Book.” . . . The Library of America shares Virginia Woolf’s opinion of Henry James’ conversational skills, and notes 10 recent novels that use James as a fictional character. . . . Mark Athitakis points to a Dale Peck review, originally meant to be published in The Atlantic, praising Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day. . . . Sharmila Sen imagines translations as the wives of original texts: “If fidelity represents a certain kind of stasis, then the beauty of a translation lies in the very promise of infidelities it can inspire.” . . . Last but not least, a belated happy birthday to The Casual Optimist, the smart books/design blog that turned two last week.

Thursday, September 30th, 2010

In the Ether

Monday, September 27th, 2010

The Cherry & the Pit(s)

A continuing series that highlights books recently acquired by publishing houses for future release. Each post features a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

This feature’s been away for a bit, so two pits for you today:

The Cherry:

Holly George-Warren’s A Man Called Destruction: The Life & Music of Alex Chilton from the Box Tops to Big Star to Backdoor Man, a biography of the iconoclastic and influential musician drawn from interviews conducted with Chilton before his March 2010 death as well as with his friends, family, and music colleagues.

The Pits:

Elsa Watson’s Dog Days, in which a small, town cafe owner is struck by lightning and switches bodies with the lost dog following her, then must struggle with her new canine instincts to overcome her fear of dogs and learn how to live and love with the carefree perspective of a dog.

Nina Benneton’s Compulsively Mr. Darcy, about a germ-phobic philanthropist William Darcy who meets granola, infectious-disease Doctor Bennet during one crazy trip to Vietnam to adopt a trendy orphan.

Friday, September 24th, 2010

Keeping the Books

After David Markson died earlier this year, many books from his personal collection started showing up in random places on the shelves of The Strand, New York’s great repository of used (and new) books. There was a bit of uproar at the time (if there can be a bit of uproar) from those who wondered how it could possibly happen that an acclaimed American writer’s books ended up in the hands of various Strand diggers rather than a protected home, perhaps in the academy. No one seemed interested in investigating whether this was simply Markson’s desire. But Craig Fehrman has:

In David Markson’s case, the easiest explanation for why his books ended up at The Strand is that he wanted them to. Markson, who lived near the bookstore, would stop by three or four times a week. The Strand, in turn, hosted his book signings and maintained a table of his books, and Markson’s daughter, Johanna, says he frequently told her in his final years to take his books to The Strand. “He said they’d take good care of us,” she says.

That comes from a broader piece Fehrman wrote about authors’ libraries for the Boston Globe, in which he considers the fate of personal collections when famous authors die:

Most people might imagine that authors’ libraries matter—that scholars and readers should care what books authors read, what they thought about them, what they scribbled in the margins. But far more libraries get dispersed than saved. In fact, David Markson can now take his place in a long and distinguished line of writers whose personal libraries were quickly, casually broken down. Herman Melville’s books? One bookstore bought an assortment for $120, then scrapped the theological titles for paper. Stephen Crane’s? His widow died a brothel madam, and her estate (and his books) were auctioned off on the steps of a Florida courthouse. Ernest Hemingway’s? To this day, all 9,000 titles remain trapped in his Cuban villa.

I’m not sure I agree that libraries are inherently interesting or revealing. I’m not a famous writer, but I’m a big reader, and my shelves are home to several books I didn’t love, many books I haven’t read, and a few books temporarily on loan from friends. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say that I’m not sure they are so interesting that an author like Markson shouldn’t be allowed to give them to his favorite shop down the block. Fehrman writes about the efforts—noble or crazy, depending on your perspective—of some scholars to retroactively compose a list of all the books an author owned: “The effort and ingenuity behind these lists can be astounding, as scholars will sift through diaries, receipts, even old library call slips. A good example is Alan Gribben’s Mark Twain’s Library: A Reconstruction, which runs to two volumes and took nine years to complete.”

On his own blog, Fehrman expanded on his article with an interesting post about Melville, and about the strategies employed by university archivists looking for a big catch.

Wednesday, September 22nd, 2010

Paris Review Interview Bonanza

The four collections of Paris Review interviews published by Picador in recent years are beautiful books worth owning. (I wrote about the series and the fourth volume here. Oh, and actually wrote about earlier volumes at another venue, here and here and here.) Now, as part of new editor Lorin Stein’s regime, all of the Review’s interviews are available online.

The four collections of Paris Review interviews published by Picador in recent years are beautiful books worth owning. (I wrote about the series and the fourth volume here. Oh, and actually wrote about earlier volumes at another venue, here and here and here.) Now, as part of new editor Lorin Stein’s regime, all of the Review’s interviews are available online.

Browsing through the subjects by last name, I get the distinct sense that I’ll be losing many, many hours to this archive, though the negative connotations of “losing” are not at all apt here. Just three that I will be diving into soon: Michiko Kakutani (and the magazine’s editors) interviewing Woody Allen. John Sullivan talking to Guy Davenport. And George Plimpton and the great John Gregory Dunne (pictured above), who waste no time getting started, beginning like this:

Plimpton: Your work is populated with the most extraordinary grotesqueries—nutty nuns, midgets, whores of the most breathtaking abilities and appetites. Do you know all these characters?

Dunne: Certainly I knew the nuns. You couldn’t go to a parochial school in the 1940s and not know them. They were like concentration-camp guards. They all seemed to have rulers and they hit you across the knuckles with them. The joke at St. Joseph’s Cathedral School in Hartford, Connecticut, where I grew up, was that the nuns would hit you until you bled and then hit you for bleeding. Having said that, I should also say they were great teachers. As a matter of fact, the best of my formal education came from the nuns at St. Joseph’s and from the monks at Portsmouth Priory, a Benedictine boarding school in Rhode Island where I spent my junior and senior years of high school. The nuns taught me basic reading, writing, and arithmetic; the monks taught me how to think, how to question, even to question Catholicism in order to better understand it. The nuns and the monks were far more valuable to me than my four years at Princeton. I’m not a practicing Catholic, but one thing you never lose from a Catholic education is a sense of sin and the conviction that the taint on the human condition is the natural order.

Tuesday, September 21st, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Charles Baxter reviews Jonathan Franzen’s latest. Finally, someone keeps this book from slipping under the radar. (”Freedom operates as a kind of morality play in which all the major players are drawn toward actions they should not perform and objects they either cannot or should not possess. . . . [Its] ambition is to be the sort of novel that sums up an age and that gets everything into it, a heroic and desperate project.”) . . . James Marcus reviews Robert Fox’s We Were There, which compiles firsthand accounts of how people experienced the 20th century. Marcus thinks the emphasis on World War II crowds out other events, but finds the book “valuable” in the end: “It vividly illustrates a general principle of such first-person testimonies: they are most interesting when they surprise us, when some element of human perversity creeps into the picture and messes with our expectations.” . . . “Told in a voice that echoes the magic cadences of Toni Morrison or the folk wisdom of Zora Neale Hurston’s collected oral histories,” Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns is, according to Lynell George, a “lush, expansive and harrowing history of the decades-long exodus of blacks, which became known as the Great Migration . . . when black people in the South disappeared, often under the cover of night, frequently leaving their sharecropper’s tools in the fields, their future plans and whereabouts a mystery to those they left behind.” . . . Susan Casey has written about great white sharks, and her new book returns to the ocean to look at surfers and extremely large waves. Matt Robinson says the book is “a sort of surfing safari, part educational (Ms. Casey interviews oceanographers, physicists, marine insurers) and part explorational—a search for something to gawp at.” . . . With Cultures of War, Pulitzer-winning historian John Dower has written a “thought-provoking, scholarly and deeply polemical book” about the lessons to be learned from Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, 9/11, and the Iraq war.

Charles Baxter reviews Jonathan Franzen’s latest. Finally, someone keeps this book from slipping under the radar. (”Freedom operates as a kind of morality play in which all the major players are drawn toward actions they should not perform and objects they either cannot or should not possess. . . . [Its] ambition is to be the sort of novel that sums up an age and that gets everything into it, a heroic and desperate project.”) . . . James Marcus reviews Robert Fox’s We Were There, which compiles firsthand accounts of how people experienced the 20th century. Marcus thinks the emphasis on World War II crowds out other events, but finds the book “valuable” in the end: “It vividly illustrates a general principle of such first-person testimonies: they are most interesting when they surprise us, when some element of human perversity creeps into the picture and messes with our expectations.” . . . “Told in a voice that echoes the magic cadences of Toni Morrison or the folk wisdom of Zora Neale Hurston’s collected oral histories,” Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns is, according to Lynell George, a “lush, expansive and harrowing history of the decades-long exodus of blacks, which became known as the Great Migration . . . when black people in the South disappeared, often under the cover of night, frequently leaving their sharecropper’s tools in the fields, their future plans and whereabouts a mystery to those they left behind.” . . . Susan Casey has written about great white sharks, and her new book returns to the ocean to look at surfers and extremely large waves. Matt Robinson says the book is “a sort of surfing safari, part educational (Ms. Casey interviews oceanographers, physicists, marine insurers) and part explorational—a search for something to gawp at.” . . . With Cultures of War, Pulitzer-winning historian John Dower has written a “thought-provoking, scholarly and deeply polemical book” about the lessons to be learned from Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, 9/11, and the Iraq war.

Thursday, September 16th, 2010

When One Translation Is Not Enough

The Paris Review’s blog has a new look, to coincide with the first issue published under the guidance of Lorin Stein, and it also has a guest post by Lydia Davis, who will be writing on the site over the next two weeks about “the tasks and sins of the translator.” Davis’ new translation of Madame Bovary

The Paris Review’s blog has a new look, to coincide with the first issue published under the guidance of Lorin Stein, and it also has a guest post by Lydia Davis, who will be writing on the site over the next two weeks about “the tasks and sins of the translator.” Davis’ new translation of Madame Bovary is out later this month.

Wise people like to say, wisely: Every generation needs a new translation. It sounds good, but I believe it isn’t necessarily so: If a translation is as fine as it can be, it may match the original in timelessness, too—it may deserve to endure. In fact, it may endure even if it is not all it should be in style and faithfulness. The C. K. Scott Moncrieff translation of most of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (which he called, to Proust’s distress, Remembrance of Things Past) was written in an Edwardian English more dated than Proust’s own prose, and it departed consistently from the French original. Yet it had such conviction, on its own terms, and was so well written, if you liked a certain florid style, that it prevailed without competition for eighty years. (There was also, of course, the problem of finding a single individual to do a new translation of a 3,000-page book—an individual who wouldn’t die before finishing it, as Scott Moncrieff had. This problem Penguin solved at last by appointing a group to do it.)

Thursday, September 16th, 2010

Walnut What?

I keep reading things about Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom that make me extremely wary of it. Today’s wary-making fact: It features an indie rock band called Walnut Surprise. This is one of those small details that might actually mean a lot. Franzen has consciously positioned himself as the foremost chronicler of How We Live Now (and reaped significant rewards for the positioning), but I remain unconvinced that he knows How We Live Now. There are, of course, thousands of bands with terrible names out there. Whether any of those names are as uniquely terrible as Walnut Surprise is a debate for another time. From what I understand—and yes, I should just read the book, which I plan to do—the name and the band are not meant for purely satirical purposes. In other words, the band is taken seriously (up to a point), etc. The name Walnut Surprise, in my humble opinion, for a band that is hailed by almost anyone, is a minor indication that the person who came up with that name is Out of Touch.

I keep reading things about Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom that make me extremely wary of it. Today’s wary-making fact: It features an indie rock band called Walnut Surprise. This is one of those small details that might actually mean a lot. Franzen has consciously positioned himself as the foremost chronicler of How We Live Now (and reaped significant rewards for the positioning), but I remain unconvinced that he knows How We Live Now. There are, of course, thousands of bands with terrible names out there. Whether any of those names are as uniquely terrible as Walnut Surprise is a debate for another time. From what I understand—and yes, I should just read the book, which I plan to do—the name and the band are not meant for purely satirical purposes. In other words, the band is taken seriously (up to a point), etc. The name Walnut Surprise, in my humble opinion, for a band that is hailed by almost anyone, is a minor indication that the person who came up with that name is Out of Touch.

Tuesday, September 14th, 2010

Equal Before the Lens

This post was written by Jacob Silverman.

This post was written by Jacob Silverman.

How do you like your irony? The answer may determine how you feel about Created Equal, Mark Laita’s book of 105 photographic diptychs. If you don’t mind irony that comes in the form of a wink, a knowing tilt of the head, a sly gesture tending toward the obvious, then you’ll probably appreciate the juxtapositions that Laita makes with these 210 portraits culled from a decade of photographing Americans throughout the lower 48 states.

Most of the photos are black-and-white, a dark muslin backdrop and diffuse lighting allowing for a full view of the subjects, most of whom face the camera directly, usually bearing an expression just this side of angry or bemused. Below each photograph are the subject’s name, a descriptive label (usually his or her profession), and a date and location. There are some recurring types: sex workers, pimps, cops, convicts, priests and nuns, gamblers, models and bodybuilders, the mentally disabled (including several identified as inbred). Taken on their own, the photos are aesthetically interesting and well composed, but Laita’s project is more provocative for how he labels and arranges his subjects.

The title of the book begs us to draw equivalences between those depicted. The captions help us along, recasting subjects as something entirely different from what they appear. The man in a space suit is obviously an astronaut (confirmed by the underlying descriptor), yet we have no idea who the casually dressed, middle-aged woman on the adjacent page is until we read that she’s an alien abductee (self-proclaimed, I assume). It’s a clever juxtaposition on Laita’s part, but it also points to a limitation of his scheme: appreciating these diptychs often hinges on the reductive labels applied to them.

Laita’s approach is one of enforced harmony. The juggler and the air traffic controller, presumably paired because both keep track of complicated patterns in the air. A ballerina and a boxer, telling us something about physical grace. The stock traders and the demolition derby crew, varieties of destruction. In a few inspired cases, the labels are almost irrelevant. The stripper who occupies both sides of a diptych—naked in one, clothed and holding a grocery bag in the other—is striking because she’s almost unrecognizable from one photograph to the next but both images reflect fundamental aspects of her identity. In another set, a boy holding a jar of fireflies is paired with a moonshiner, each grasping a glass jar that holds something precious to its owner.

Laita’s approach is one of enforced harmony. The juggler and the air traffic controller, presumably paired because both keep track of complicated patterns in the air. A ballerina and a boxer, telling us something about physical grace. The stock traders and the demolition derby crew, varieties of destruction. In a few inspired cases, the labels are almost irrelevant. The stripper who occupies both sides of a diptych—naked in one, clothed and holding a grocery bag in the other—is striking because she’s almost unrecognizable from one photograph to the next but both images reflect fundamental aspects of her identity. In another set, a boy holding a jar of fireflies is paired with a moonshiner, each grasping a glass jar that holds something precious to its owner.

Many of these diptychs, though, are screamingly obvious—a real estate agent and a homeless woman, a bank robber and sheriff’s deputies, a black Baptist minister and Ku Klux Klan members—while others are too insistent on their connections, like the bug-eyed man with his mail-order wife set against a movie producer with his much younger wife. There’s a sense of abridgment here, of too much interpretation being done for us. The man wearing a “warden” badge is called an “executioner,” but he could, of course, be identified as a prison warden—a label that’s probably more accurate and certainly less political. (He, by the way, is paired with a fortuneteller.)

While Created Equal’s introduction, written by Ingrid Sischy, tells us that Laita spent less than 10 minutes with some of his subjects, the notes section at the end of the book provides some illuminating details. One of the pimps was shot and killed a week after his photograph was taken; one male cross-dresser was new to the lifestyle and felt “excited about interacting with someone as a woman;” the “only thing that bothers” the executioner “is that [his work] doesn’t bother” him; the Latino dishwasher, wearing a hairnet and appearing close to tears, works in a “small 24-hour deli in Manhattan, where none of the employees speak the same language and everyone seems to hate each other, including the customers.” There are such endnotes for perhaps a third of the photographs, and they’re fascinating. They indicate that Laita, when he takes the time to listen to his subjects, is able to craft deceptively emotive scenes that gesture at something larger than themselves–like an Amy Hempel story visualized. I appreciate the humanistic spirit of a book that attempts to call us all equal (especially when many of these people are culled from society’s margins), and that doesn’t glamorize its subjects, but it also seems restricted by the form Laita has chosen. I look forward to a future work that builds on his demonstrated ability to capture compelling subjects, while presenting them through a less constricted lens.

While Created Equal’s introduction, written by Ingrid Sischy, tells us that Laita spent less than 10 minutes with some of his subjects, the notes section at the end of the book provides some illuminating details. One of the pimps was shot and killed a week after his photograph was taken; one male cross-dresser was new to the lifestyle and felt “excited about interacting with someone as a woman;” the “only thing that bothers” the executioner “is that [his work] doesn’t bother” him; the Latino dishwasher, wearing a hairnet and appearing close to tears, works in a “small 24-hour deli in Manhattan, where none of the employees speak the same language and everyone seems to hate each other, including the customers.” There are such endnotes for perhaps a third of the photographs, and they’re fascinating. They indicate that Laita, when he takes the time to listen to his subjects, is able to craft deceptively emotive scenes that gesture at something larger than themselves–like an Amy Hempel story visualized. I appreciate the humanistic spirit of a book that attempts to call us all equal (especially when many of these people are culled from society’s margins), and that doesn’t glamorize its subjects, but it also seems restricted by the form Laita has chosen. I look forward to a future work that builds on his demonstrated ability to capture compelling subjects, while presenting them through a less constricted lens.

Jacob Silverman is a contributing online editor for the Virginia Quarterly Review. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The National, The Daily Beast, and many other publications.

Friday, September 10th, 2010

100 Issues Young

A belated congratulations to Michael Schaub and Jessa Crispin at Bookslut, who published the site’s 100th issue earlier this week. A remarkable achievement.

Quieter than I expected around here this week, for personal reasons (nothing bad). Full speed next week: new reviews in Circulating, the return of regular blogging, and a general shaking off of summer and full embrace of a busy fall.

Wednesday, September 8th, 2010

The Paranoid Style

New on the Backlist this week, Tim Crimmins writes at length about America’s Founding Fathers, Britain’s radical Whigs, and the Tea Party. He begins the piece by citing Richard Hofstadter’s “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” an essay that first appeared in the November 1964 issue of Harper’s. The entire thing is available online. It begins:

New on the Backlist this week, Tim Crimmins writes at length about America’s Founding Fathers, Britain’s radical Whigs, and the Tea Party. He begins the piece by citing Richard Hofstadter’s “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” an essay that first appeared in the November 1964 issue of Harper’s. The entire thing is available online. It begins:

American politics has often been an arena for angry minds. In recent years we have seen angry minds at work mainly among extreme right-wingers, who have now demonstrated in the Goldwater movement how much political leverage can be got out of the animosities and passions of a small minority. But behind this I believe there is a style of mind that is far from new and that is not necessarily right-wing. I call it the paranoid style simply because no other word adequately evokes the sense of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy that I have in mind. In using the expression “paranoid style” I am not speaking in a clinical sense, but borrowing a clinical term for other purposes. I have neither the competence nor the desire to classify any figures of the past or present as certifiable lunatics. In fact, the idea of the paranoid style as a force in politics would have little contemporary relevance or historical value if it were applied only to men with profoundly disturbed minds. It is the use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant.

Of course this term is pejorative, and it is meant to be; the paranoid style has a greater affinity for bad causes than good. But nothing really prevents a sound program or demand from being advocated in the paranoid style. Style has more to do with the way in which ideas are believed than with the truth or falsity of their content. I am interested here in getting at our political psychology through our political rhetoric. The paranoid style is an old and recurrent phenomenon in our public life which has been frequently linked with movements of suspicious discontent.

Friday, September 3rd, 2010

A Fledgling Sci-Fi Collection

That last post inspired me to take a quick look around my own bookshelves. I’d say the apartment currently houses between 800 and 900 books (his and hers), and I have a few hundred more in storage. I’m always adding to that number, and not always in ways that make a ton of sense. For instance, I will very occasionally—maybe once every few years—buy a sci-fi book, despite the fact that the last sci-fi book I finished was probably something by Isaac Asimov when I was something like 13 years old. This is not to impugn sci-fi, but just to say I never had much of a natural taste for it. A few years back, I bought Ender’s Game

That last post inspired me to take a quick look around my own bookshelves. I’d say the apartment currently houses between 800 and 900 books (his and hers), and I have a few hundred more in storage. I’m always adding to that number, and not always in ways that make a ton of sense. For instance, I will very occasionally—maybe once every few years—buy a sci-fi book, despite the fact that the last sci-fi book I finished was probably something by Isaac Asimov when I was something like 13 years old. This is not to impugn sci-fi, but just to say I never had much of a natural taste for it. A few years back, I bought Ender’s Game, widely considered a classic of the genre. It remains perched on a bottom shelf.

Last night, I bought a copy of Marsbound by Joe Haldeman, having recently read a review that piqued my interest. Perhaps after I collect a few more titles—and there are plenty of guides for help—I’ll get around to reading them.

Friday, September 3rd, 2010

“I don’t want to read them. I just want them around.”

Scott David Herman notes that his book collection has passed a milestone:

As of last week, it grieves me to say, our book collection has finally broken a thousand. The tally as of this writing is one thousand and three. Some are hers, some are mine, some are ours. Regarding the mine-and-ours: Don’t ask me how many of them I’ve read or will read or will even ever crack open and flip through in search of something, I beg you. Don’t ask me how well I remember or understand the ones I have read. Just don’t go there. The answers will reflect poorly on all involved. The shame of the high books-bought-to-books-read ratio is of course comfortingly widespread among us of the book-nerd persuasion. Let’s just round down and say I haven’t read any of them. I don’t want to read them. I just want them around. I require them in my home. And I must have more.

(Via Levi Stahl)

Thursday, September 2nd, 2010

Something Must Be Wrong

At the magazine of Wabash College, Jason Boog writes about losing his job and finding some measure of solace in the work of 1930s novelists. It begins:

I lost my job in December 2008, unemployed at the beginning of the longest, coldest winter I can remember in New York City.

Up until then, everything had been going swimmingly: I was a staff writer at an investigative reporting publication, taught an undergraduate journalism class, and proposed to my girlfriend in a fairytale forest along the Hudson River. Suddenly, I had to tell my friends, relatives, and students how I had failed.

Out of everything I read during those gloomy months, I found the most comfort in Maxwell Bodenheim—an author who lost everything during the Great Depression. In 1934, he wrote: “There’s something wrong with this world all right, but I can’t put my finger on it. . . . Something must be wrong when a fellow can’t get a decent wage, can’t tell when he’s going to be fired, can’t look forward to any promise of happiness. Something is rotten somewhere.”

Thursday, September 2nd, 2010

And the Winners Are

Congratulations to readers Merlin Brittenham and Dan (who blogs at Imagined Icebergs), who, respectively, won a copy of The Varieties of Religious Experience and The Heart of William James.

There will be more giveaways soon, probably related to the idea of older favorites. Stay tuned.

Wednesday, September 1st, 2010

In the Ether

Mark Pilkington recommends 10 books about UFOs that are “either informative, entertaining, puzzling or all three at once.” . . . Lorin Stein discusses the art of the Paris Review’s famous interviews, and offers a peek at a few future subjects. . . . Penguin launches a new monthly radio series, “The Literary Life,” with guests Rosanne Cash, Maile Meloy, Doug Dorst, and Sloane Crosley. . . . Independent book sellers recommend 40 books from independent publishers that they will be recommending to customers over the next few months. . . . Andrew Pettegree is interviewed about the advent of printed books. (“There’s quite a little similarity in the first generation of print with the dot-com boom and bust of the ’90s.”) . . . Sad news to long-live-print folks like myself: The next edition of the Oxford English Dictionary will be available only in e-form. . . . Jonathan Lethem talks about leaving his beloved Brooklyn for California. . . . I’m going to start reading the work of Thomas Bernhard soon; perhaps as soon as this afternoon. Scott Bryan Wilson offers a checklist of his work. . . . Rick Gekoski on “how to be a good literary loser.” . . . Ian Hocking, novelist, writes movingly about the decision to stop writing fiction. (“Someone wrote – [Stephen] King again, I think – that a writer is a person who will write no matter what. In other words, if you lock them up in a cell without pen or pencil, they’ll write on the wall in their own blood. I didn’t believe that when I read it and I don’t believe it now. Even Stephen King comes to a point when the blood dries up.”)

Mark Pilkington recommends 10 books about UFOs that are “either informative, entertaining, puzzling or all three at once.” . . . Lorin Stein discusses the art of the Paris Review’s famous interviews, and offers a peek at a few future subjects. . . . Penguin launches a new monthly radio series, “The Literary Life,” with guests Rosanne Cash, Maile Meloy, Doug Dorst, and Sloane Crosley. . . . Independent book sellers recommend 40 books from independent publishers that they will be recommending to customers over the next few months. . . . Andrew Pettegree is interviewed about the advent of printed books. (“There’s quite a little similarity in the first generation of print with the dot-com boom and bust of the ’90s.”) . . . Sad news to long-live-print folks like myself: The next edition of the Oxford English Dictionary will be available only in e-form. . . . Jonathan Lethem talks about leaving his beloved Brooklyn for California. . . . I’m going to start reading the work of Thomas Bernhard soon; perhaps as soon as this afternoon. Scott Bryan Wilson offers a checklist of his work. . . . Rick Gekoski on “how to be a good literary loser.” . . . Ian Hocking, novelist, writes movingly about the decision to stop writing fiction. (“Someone wrote – [Stephen] King again, I think – that a writer is a person who will write no matter what. In other words, if you lock them up in a cell without pen or pencil, they’ll write on the wall in their own blood. I didn’t believe that when I read it and I don’t believe it now. Even Stephen King comes to a point when the blood dries up.”)

Monday, August 30th, 2010

An Extension for Mr. James

William James Week was scheduled to end on Friday, but then I received a guest post from Robert D. Richardson, and since Richardson’s biography of James is one of my all-time favorite books, it gives me a thrill to extend the week to today. Richardson’s contribution is the post immediately below this one.

I’ll be traveling back to Brooklyn today from an annual visit to Saratoga Springs, and non-James-related activity will resume in full tomorrow. Lots of things are planned for the fall. In the meantime, a reminder that I’m still accepting entries for two book giveaways, here and here.

Monday, August 30th, 2010

The War on War (Guest Post by Robert D. Richardson)

Robert D. Richardson is an award-winning biographer whose books include Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind, Emerson: The Mind on Fire

, and William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism.

He edited The Heart of William James

, being published this week by Harvard University Press.

William James, the greatest American philosopher and a founding figure of both modern psychology and modern religious studies, died 100 years ago last week. It is also just a century since the publication of James’ landmark manifesto, “The Moral Equivalent of War,” one of the last things published before his death. James was anti-imperialist, and he opposed, as did a few other Americans, the Spanish-American war, especially its extension to the Philippines.

By 1910, James was against war itself. His notion of a “war against war,” as he puts it, had been building for at least a decade. His position, unusual still today among peace advocates, recognizes that war is a deeply attractive thing for many of us, and that we do not in fact want peace—at least not entirely. He wrote before D.H. Lawrence observed that “the essential American is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer.” And long before Simone Weil’s “The Iliad, or, the Poem of Force,” James noted that “the Iliad is one long recital of how Diomedes, and Ajax, Sarpedon and Hector killed.” It is the greatest strength of James’ argument that he seriously recognizes the grip war has on us and will continue to have. Rather than say we all love peace, let’s not fight, James instead tries to harness the war-spirit and turn it against itself. We will have to kill war.

James made two concrete proposals for how this might be done. In The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), he reached back to Thoreau’s Walden and the idea, discussed in the first chapter of that classic, of voluntary poverty. (When Americans see that phrase, they see “poverty” written in boldface. We must train ourselves to see “voluntary,” meaning willed, written in caps and printed in red.)

“What we now need to discover in the social realm is the moral equivalent of war,” James wrote in Varieties, “something heroic that will speak to men as universally as war does, and yet will be as compatible with their spiritual selves as war has proved itself to be incompatible. . . . May not voluntarily accepted poverty be ‘the strenuous life’ without the need of crushing weaker peoples?”

By the time he wrote “The Moral Equivalent of War,” James had dropped the idea of voluntary poverty or simplicity—the sort of thing advocated in Walden, and by Wendell Berry, and by the modern “freegans”—in favor of something very close to the modern idea of the Peace Corps. “To coal and iron mines, to freight trains, to fishing fleets in December, to dish-washing, clothes-washing, and window-washing, to road building and tunnel making, to foundries and stoke holes, and to the frames of skyscrapers, would our gilded youth be drafted off, according to their choice, to get the childishness knocked out of them, and to come back into society with healthier sympathies and soberer ideas.”

It was not an accident that when the Civilian Conservation Corps built a leadership camp in Sharon Vermont in 1940, it was called Camp William James. But many Americans still have an unshakable belief that violence is the only real way to settle disputes and is fundamental to manhood. James himself noted that the only tax we pay willingly is the war tax.

The war against war has not been going very well lately, but we must take what solace we can in the fact that the struggle continues. We have had the war on poverty, the war on drugs, and many other such initiatives, and the idea that there might really be a moral equivalent of war refuses to die. If and when war itself is finally vanquished, it will be in the way James first showed. And as much as we need a concrete proposal, a workable mechanism, a specific way, we also need the resolve to carry it through. And here, just as the peace movement needs to learn from its enemy, war, how to fight back, we can learn from our former enemies something about resolve. It was an article of faith among old communist organizers that there was never more than 10% of the people who were true, committed revolutionaries, and never more than 10% who were unalterably opposed. The great struggle, then, is to get the overwhelming 80% in the uncommitted middle over to your side.

The war against war has not been won, but neither has it been irretrievably lost. We owe to William James the very idea that there might even be such a thing as a moral equivalent to—and not just a moral argument against—war.

Friday, August 27th, 2010

A Selection

From “The Sick Soul” by William James, part of The Varieties of Religious Experience:

From “The Sick Soul” by William James, part of The Varieties of Religious Experience:

Recent psychology has found great use for the word ‘threshold’ as a symbolic designation for the point at which one state of mind passes into another. Thus we speak of the threshold of a man’s consciousness in general, to indicate the amount of noise, pressure, or other outer stimulus which it takes to arouse his attention at all. One with a high threshold will doze through an amount of racket by which one with a low threshold would be immediately waked. Similarly, when one is sensitive to small differences in any order of sensation we say he has a low ‘difference-threshold’—his mind easily steps over it into the consciousness of the differences in question. And just so we might speak of a ‘pain-threshold,’ a ‘fear-threshold,’ a ‘misery-threshold,’ and find it quickly overpassed by the consciousness of some individuals, but lying too high in others to be often reached by their consciousness. The sanguine and healthy-minded live habitually on the sunny side of their misery-line, the depressed and melancholy live beyond it, in darkness and apprehension. There are men who seem to have started in life with a bottle or two of champagne inscribed to their credit; whilst others seem to have been born close to the pain-threshold, which the slightest irritants fatally send them over.

Does it not appear as if one who lived more habitually on one side of the pain-threshold might need a different sort of religion from one who habitually lived on the other? This question, of the relativity of different types of religion to different types of need, arises naturally at this point, and will become a serious problem ere we have done. But before we confront it in general terms, we must address ourselves to the unpleasant task of hearing what the sick souls, as we may call them in contrast to the healthy-minded, have to say of the secrets of their prison-house, their own peculiar form of consciousness. Let us then resolutely turn our backs on the once-born and their sky-blue optimistic gospel; let us not simply cry out, in spite of all appearances, “Hurrah for the Universe!— God’s in his Heaven, all’s right with the world.” Let us see rather whether pity, pain, and fear, and the sentiment of human helplessness may not open a profounder view and put into our hands a more complicated key to the meaning of the situation.

Thursday, August 26th, 2010

William James Week Giveaway #2

Next week, Harvard University Press will publish The Heart of William James

Next week, Harvard University Press will publish The Heart of William James, an anthology of James’ writing edited by Robert D. Richardson, whose biography of James

is terrific.

The Heart of William James includes 17 essays, including “What Is an Emotion?,” “The Moral Equivalent of War,” and “The Sick Soul,” perhaps my favorite example of James’ work. The publisher says, “Richardson’s introductions site the works in the larger scheme of James’ thought, making this book ideal for the reader new to James, or for anyone looking for a portable James. The pieces are presented in chronological order, and each is complete, enabling the reader to follow James’ arguments as he intended.”

So, who would like a copy? E-mail me at john[at]thesecondpass[dot]com with “Heart” in the title. I’ll accept entries for this one until 11:59 p.m. on Tuesday, August 31. Otherwise, rules for this giveaway are the same as for the previous one. If you enter both and happen to win both, you will have to choose one and a re-drawing will be held for the other book.

Thursday, August 26th, 2010

When William Met Sigmund (Guest Post by Levi Asher)

Levi Asher is a writer and website developer. His blog Literary Kicks has been online since 1994.

Levi Asher is a writer and website developer. His blog Literary Kicks has been online since 1994.

Psychology is often concerned with origins, but the origin of modern psychology itself is murky. The field was born not from a great idea but from the lack of one. Philosophers had always studied the mind while scientists studied the physical universe, but the scientific revolution that followed the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species in 1859 seemed to call for a newly rigorous, evidence-based approach to the mysteries of the human mind. The word psychology already existed by then (in its Greek, Latin, French, German, Russian, and English equivalents), but it took a few brave souls to step forward and try to define an actual discipline worthy of the name.

In the U.S., William James was the first brave soul. In 1875, as a 33-year-old teacher of anatomy and physiology at Harvard, filled with broad and exciting ideas but mostly unknown to the world, James sent a letter to Harvard president Charles W. Eliot proposing a new course in psychology. Eliot approved the idea and James began teaching it, the first psychology course anywhere in the world, in 1876. He also began writing a textbook, The Principles of Psychology, which also would have been the world’s first if James had finished it quickly—but he did the opposite, working on it until 1890, by which time many other textbooks had been produced.

Not long after Principles was published, James began to reach a larger audience with his speeches and writings on philosophy, religion, and the nature of truth. And the field of psychology found its own Darwin—an electrifying presence with a revolutionary theory to prove—in Sigmund Freud, whose Interpretation of Dreams was published in 1900.

Freud and James met once, in 1909, at a gathering of psychologists at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. Several other soon-to-be-notable psychologists, including Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, and Ernest Jones had arrived with Freud. (Some, notably Jung, would later break with him, but at the time they formed his loyal entourage). Freud was clearly the star attraction at the conference, and it was to hear him speak that James, by this time an elderly eminence, 14 years older than Freud and in failing health, made the short trip to Worcester from Boston.

According to all accounts, Freud and James were eager to meet each other. The two men ended their brief encounter by strolling alone together to a train station, and a dramatic scene unfolded: James, suffering from heart problems, suddenly felt an attack of angina pectoris coming on, and asked Freud to walk ahead alone so he could gather himself. This appears to have ended their chance for a deeper conversation, and later accounts of the meeting by both men hint at an undefined tension underlying the friendly meeting.

James and Freud shared a fascination with the phenomenon of human consciousness. They both believed entirely in the essential, irreducible willfulness of human nature. It was James’ greatest discovery that our needs, desires, and hopes are the cornerstones of our belief systems. It was Freud’s greatest discovery that our needs, desires, and hopes have a mind of their own—the unconscious mind—and, in this capacity, influence everything we do. On the biggest questions of life, meaning, and existence, Jamesian philosophy and Freudian psychology can be harmonious.

Yet the two could be described as ideological opposites as well. James had great intellectual passion for religion, and Freud was a passionate atheist who wrote a book about religion called The Future of an Illusion. James was also decidedly a pluralist, whereas Freudian psychology located sexuality as the singular emotional core (and core trauma) of human existence. A broad, anti-dogmatic thinker like James could never fall for a belief system based on a single cause, a single anything. Life, James believed, was too rich for that.

One can only wonder at the private bemusement with which James might have greeted the outrageously controversial Freud in 1909. In a private letter, he gently mocked Freud’s theories about dreams as the key to psychological revelation. But his own Principles of Psychology inexplicably contains only a simple half page about the phenomenon of dreaming (though it contains painfully long sections about, for instance, the perception of space and the phenomenon of optical illusions).

James knew that Freud’s energetic research had value, whatever its flaws or overreaching. It also seems likely that Freud’s more brazen statements would have pleased James for their audacity. Like Freud, James was no prude, and he didn’t mind shocking the academy every now and then.

Finally, as a father of pragmatism, James admired the fact that Freud’s reputation rested on actual clinical success. Psychoanalysis was the Freudian “pragma,” and it was known to actually cure patients in the field. By generously embracing and lending his credibility to the upstart Freud, James was acting as a pluralist, a pragmatist, and, above all, a man with love to spare for his embattled fellow thinkers.

As for explaining the awkwardness between the aging American genius and his younger European rival, a Freudian interpretation might come in handy.

Wednesday, August 25th, 2010

Spooky Visitations (Guest Post by Levi Stahl)

In addition to holding a full-time job at the University of Chicago Press, Levi Stahl is the poetry editor for the Quarterly Conversation and a blogger at I’ve Been Reading Lately.

As someone who has never felt even the slightest stirrings of religious feeling, I find the most compelling part of William James’ The Varieties of Religious Experience to be a portion of the third lecture (“The Reality of the Unseen”) called “Examples of ‘sense of presence.’ ” James opens that section with the proposition—set out, as is his tendency in his philosophical writing, as of course agreed rather than needing to be proved—that the

whole array of our instances leads to a conclusion something like this: It is as if there were in the human consciousness a sense of reality, a feeling of objective presence, a perception of what we may call “something there,” more deep and more general than any of the special and particular “senses” by which the current psychology supposes existent realities to be originally revealed.

From there, he proceeds to relate a number of firsthand accounts of spooky visitations, of instances where reliable people were certain, despite improbabilities, that they were being visited by some indefinable presence. Here is one testimonial:

It was about September, 1884, when I had the first experience. On the previous night I had had, after getting into bed at my rooms in College, a vivid tactile hallucination of being grasped by the arm, which made me get up and search the room for an intruder; but the sense of presence properly so called came on the next night. After I had got into bed and blown out the candle, I lay awake awhile thinking on the previous night’s experience, when suddenly I felt something come into the room and stay close to my bed. It remained only a minute or two. I did not recognize it by any ordinary sense, and yet there was a horribly unpleasant “sensation” connected with it. It stirred something more at the roots of my being than any ordinary perception. The feeling had something of the quality of a very large tearing vital pain spreading chiefly over the chest, but within the organism—and yet the feeling was not pain so much as abhorrence. At all events, something was present with me, and I knew its presence far more surely than I have ever known the presence of any fleshly living creature. I was conscious of its departure as of its coming: an almost instantaneously swift going through the door, and the “horrible sensation” disappeared.

Others follow—including one particularly evocative account of “the figure of a gray-bearded man dressed in a pepper and salt suit, squeezing himself under the crack of the door and moving across the floor of the room towards a sofa”—all serving, obliquely, to “prove the existence in our mental machinery of a sense of present reality more diffused and general than that which our special senses yield.”

Now James is well known for being open to the concepts of spiritualism—both Robert Richardson’s biography and, in a slightly poppier vein, Deborah Blum’s Ghost Hunters

, cover his engagement and eventual disillusion with the spiritualist movement. But what I find most compelling in James’ consideration of presences is the way it offers a sort of implicit connection to the work of his brother. Henry and William tended to talk past one another when it came to their writing. In his biography of William, Richardson quotes a letter to Henry that contrasts their styles, William’s

being to say a thing in one sentence as straight and explicit as it can be made, and then to drop it forever; yours being to avoid naming it straight, but by dint of breathing and sighing all round and round it, to arouse in the reader who may have had a similar perception already (Heaven help him if he hasn’t!) the illusion of a solid object, made (like the “ghost” at the Polytechnic) wholly out of impalpable materials, air, and the prismatic interferences of light, ingeniously focused by mirrors upon empty space.

Yet when the subject turns to presences, how can one help but “avoid naming it straight”? Acceptance of the concept of presences—acknowledgment that, if they are real in the mind, then in a crucial sense they are real—links William’s straightforwardness directly to Henry’s endlessly honing interiority. The world, William is seeming to accept, is what our minds make of it, which Henry, with his shadings of feeling, had been trying in one sense to say all along. And Henry, meanwhile, returned the favor in his many ghost stories, which in their most chilling moments read like nothing so much as the testimonies of visitations collected by William. Side by side, the pair make incomparable Halloween reading.

Wednesday, August 25th, 2010

William James Week Giveaway #1

As part of the William James festivities around here, I’m giving away a copy of what is probably my favorite book, The Varieties of Religious Experience. Based on a series of lectures that James delivered at the University of Edinburgh in 1901 and 1902, Varieties combines fascinating firsthand accounts of people’s experiences with James’ brilliant and timeless insights about the psychology, needs, frailty, and resilience of human beings. James was famously kind to (and drawn to) religion and the supernatural for someone as scientifically inclined as he was, but he still felt the need to acknowledge that some of the most devout might find his techniques off-putting:

As part of the William James festivities around here, I’m giving away a copy of what is probably my favorite book, The Varieties of Religious Experience. Based on a series of lectures that James delivered at the University of Edinburgh in 1901 and 1902, Varieties combines fascinating firsthand accounts of people’s experiences with James’ brilliant and timeless insights about the psychology, needs, frailty, and resilience of human beings. James was famously kind to (and drawn to) religion and the supernatural for someone as scientifically inclined as he was, but he still felt the need to acknowledge that some of the most devout might find his techniques off-putting:

It is true that we instinctively recoil from seeing an object to which our emotions and affections are committed handled by the intellect as any other object is handled. The first thing the intellect does with an object is to class it along with something else. But any object that is infinitely important to us and awakens our devotion feels to us also as if it must be sui generis and unique. Probably a crab would be filled with a sense of personal outrage if it could hear us class it without ado or apology as a crustacean, and thus dispose of it. “I am no such thing,” it would say; “I am MYSELF, MYSELF alone.”

To enter to win a copy of the book, please send an e-mail to john[at]thesecondpass[dot]com with “varieties” in the subject line. If you’d like to include a note in the body of the e-mail saying hello, or telling me the best movie you’ve attended or rented recently, feel free—I mostly hear from spambots, which can be depressing. Some important notes: 1) The edition of the book you win will not be the edition shown above. But I promise you it will not be this edition. It will be this one. 2) Your e-mail addresses will not be used for nefarious purposes involving marketing or anything else. The Second Pass is essentially a one-man shop, and the one man (me) promises privacy. 3) Winner will be drawn by a random number generator. At that time, I will contact said winner for a mailing address. So, no need to send a mailing address for now. 4) Entries will be accepted until 11:59 p.m., Eastern time, on Monday, August 30.

There will be at least one more James-related giveaway as the week progresses.

Wednesday, August 25th, 2010

“You will be discouraged, I remain happy!”

On April 18, 1874, William James wrote a letter to his brother Henry (“Dear Harry”). William was 32; Henry had recently turned 31, and was in Europe—he would eventually settle in England for the last four decades of his life. Much is made of the fact that William remained in America for his adulthood while Henry chose England, and I imagine even more could be made of it, if a full-length treatment of the subject hasn’t already been written. The excerpt below from the April 18th correspondence is taken from The Selected Letters of William James, which includes a terrific introduction by Elizabeth Hardwick, who also edited the compilation.)

My short stay abroad has given me quite a new sense of what you used to call the provinciality of Boston, but that is no harm. What displeases me is the want of stoutness and squareness in the people, their ultra quietness, prudence, slyness, intellectualness of gait. Not that their intellects amount to anything, either. You will be discouraged, I remain happy!

But this brings me to the subject of your return, of which I have thought much. It is evident that you will have to eat your bread in sorrow for a time here; it is equally evident that time . . . will provide a remedy for a great deal of the trouble, and you will attune your at present coarse senses to snatch a fearful joy from wooden fences and commercial faces, a joy the more thrilling for being so subtly extracted. Are you ready to make the heroic effort? . . . This is your dilemma: The congeniality of Europe, on the one hand, plus the difficulty of making an entire living out of original writing, and its abnormality as a matter of mental hygiene . . . on the other hand, the dreariness of American conditions of life plus a mechanical, routine occupation possibly to be obtained, which from day to day is done when ‘t is done, mixed up with the writing into which you distill your essence. . . . In short, don’t come unless with a resolute intention. If you come, your worst years will be the first. If you stay, the bad years may be the later ones, when, moreover, you can’t change. And I have a suspicion that if you come, too, and can get once acclimated, the quality of what you write will be higher than it would be in Europe. . . . It seems to me a very critical moment in your history. But you have several months to decide. Good-bye.

Tuesday, August 24th, 2010

Incoherent, Admiring, Affectionate Brothers (Guest Post by Lisa Levy)

Lisa Levy is a writer in Brooklyn, New York. Her book on modernism and biography, We Are All Modern, is forthcoming from FSG.

Three incidents serve to illustrate the contentious nature of Henry James’ relationship with his older brother William.

Three incidents serve to illustrate the contentious nature of Henry James’ relationship with his older brother William.

Both were members of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, which established the Academy of Arts and Letters in 1905. Fifty initial members were chosen by ballot. Henry was chosen in the second ballot, William in the fourth. When William found out, he declined to join, citing several reasons but most crucially writing the Academy’s secretary, “I am the more encouraged to this course by the fact that my younger and shallower and vainer brother is already in the Academy and that if I were there too, the other families represented might think the James influence too rank and strong.” Henry knew nothing about this.

The second incident concerned William’s critique of Henry’s 1904 novel The Golden Bowl, which Henry considered his finest work. William pleaded with his brother to write a book “with no twilight or mustiness in the plot.” Henry, long used to his brother’s complaints about his indirect style, replied that he would be “humiliated to write such a thing that you like it!!!” This bantering continued in The American Scene, Henry’s 1907 account of his travels, including a long visit with William’s family. William remarked that Henry was on the verge of becoming “a curiosity of literature.” Henry coolly inscribed a copy of the book, “To William James, his incoherent, admiring, affectionate Brother, Henry James, Lamb House, August 21st 1907.”

Incoherent, admiring, affectionate: these adjectives describe the brothers’ relationship in its milder form. It was also intense, cantankerous, rivalrous, and petty. William once said of the expatriate Henry, “He is really a native of the James Family, and has no other country.” The James family was a nation with a small, itinerant population: William (born 1842), Henry (1843), Garth Wilkinson (called Wilky, 1845), Robertson (called Bob, 1846) and Alice (1848). As children, the dominant William monopolized the attention of their mercurial philosopher father, Henry James, Sr., who frequently uprooted his family in a grand experiment to give his children a “sensuous education,” while the milder Henry was the favored child of their stern mother, Mary. As young men, the brothers seemed to trade off periods of invalidism (both suffered from bad backs and stomach ailments, and later in life, heart problems), as if one of them had to be the object of parental attention while the other exercised the free will that Henry Senior often preached but his children found difficult to practice. Henry Senior was so intent on his boys being that both had trouble figuring out what they ought to be doing until well into their 20s; the elder boys, that is—the younger ones were sent to fight in the Civil War and make their own way in the world.

Maybe all sons of rich fathers without the cushion of wealth themselves suffer from such problems establishing themselves, and in William and Henry James we just see a version of those problems with a certain metaphysical bent. If, as Rebecca West famously wrote in her study of Henry James, one boy grew up to write philosophy as if it were fiction and the other to write fiction as if it were philosophy, then the brothers have more in common than William’s petulance and Henry’s gentle mocking in the incidents described above. There are general and specific moments of shared values in their work, as in William’s experiments in psychology and Henry’s development of the free indirect discourse technique, which delves into the consciousness of his characters. Henry’s biographer Leon Edel points out the thematic conjunction of William’s Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) and Henry’s “The Beast in the Jungle” (1903): both deal with finding one’s place in the world, and the ways in which people use one another. What Edel does not say is how utterly Jamesian these ideas are—they are all over the brothers’ writing, from Henry’s The Portrait of a Lady (1881) to William’s Pragmatism (1907). The obsession with finding one’s place in the world was the legacy Henry Senior left his sons. How people use one another fascinated both of them, but they responded in different ways. In his personal life, William tried to rise above it, though it is key to pragmatism. Henry, however, knew it was a necessary part of life, and could be benign or malicious: he was a compulsively social man, and wrote with unmatched nuance about the connections between people, about friendships, love affairs, parents and children, even siblings.

In 1916 during his final illness, Henry told his favorite niece, William’s daughter, Peggy, several times: “I should so like to have William with me.”

Tuesday, August 24th, 2010

A Selection

From A Pluralistic Universe by William James:

Souls have worn out both themselves and their welcome, that is the plain truth. Philosophy ought to get the manifolds of experience unified on principles less empty. Like the word ’cause,’ the word ’soul’ is but a theoretic stop-gap—it marks a place and claims it for a future explanation to occupy.

This being our post-humian and post-kantian state of mind, I will ask your permission to leave the soul wholly out of the present discussion and to consider only the residual dilemma. Some day, indeed, souls my get their innings again in philosophy—I am quite ready to admit that possibility—they form a category of thought too natural to the human mind to expire without prolonged resistance. But if the belief in the soul ever does come to life after the many funeral-discourses which humian and kantian criticism have preached over it, I am sure it will be only when some one has found in the term a pragmatic significance that has hitherto eluded observation. When that champion speaks, as he well may speak some day, it will be time to consider souls more seriously.

Monday, August 23rd, 2010

How to Fathom an Emotion (Guest Post by J. C. Hallman)

J. C. Hallman is the author of several books, including The Devil Is a Gentleman: Exploring America’s Religious Fringe, a work that prominently features the life and thought of William James. Hallman’s new book is In Utopia: Six Kinds of Eden and the Search for a Better Paradise

.

I.

In 1997, Mark Edmundson offered an interesting take on Freud and the Gothic in modern culture in Nightmare on Main Street: Angels, Sadomasochism, and the Culture of Gothic. Edmundson’s view is that the resurgence of the Gothic in the 1990s proves that Freud was “mostly right.” Now I, like William James, harbor a little skepticism when it comes to Freud—but no worries: my interest in Edmundson (in regard to James) has less to do with his message than his method.

Late in Nightmare on Main Street, Edmundson takes on the nature of S & M culture (what now is more frequently called BDSM culture). He assesses some of the literature and some of the extant philosophy on the subject, and then holds forth:

Then too, it is not clear for how long S&M remains a game, stays ironic. At what point does role-playing disappear and obsession take over? For very few is an urbane irony compatible with sexual ardor. I expect that often what begins in sophisticated farce ends in an intensity and maybe too a passion that is closer to the tragic.

What’s worth considering here is the source of Edmundson’s authority. Surely, he’s incredibly well-read on his subject, but what permits him to declare that “very few” retain the ability to mesh passion and punning? Even he seems to doubt himself with equivocal language—from there, he is willing only to guess at what he “expects” is “maybe” the case.

Edmundson seems to think that this is his job. Once he’s gone on to state the thing as he sees it, a possible solution to the Gothic dilemma lies not with himself: “I would like to go further in describing such works of art and intellectual imagination, but it is at this point that the critic is compelled to step aside and the artist to take over.”

Thud! (That was William James rolling over in his grave.)

II.

“One can never fathom an emotion or divine its dictates by standing outside of it,” James wrote, in The Varieties of Religious Experience.

This was more than a quick insight. It was the credo by which James lived: he could tell us about the varieties of religious experience because in addition to exhaustive reading about them, he had experienced all of them, experimenting with their healing techniques just as he had experimented with a variety of drugs to experience alternate states of consciousness (and thereby advance his understanding of consciousness). If you want to be able to discuss something without falling back on equivocation, he believed, you have to struggle to become that which you hope to describe. Otherwise you’re just guessing.

One should expect nothing less from the man who made experience the focal center of his philosophy.

Edmundson isn’t a Jamesian—he’s a Freudian. Freud has pretty clearly had significant impact on literature (some of it magically retroactive!), but William James, too, has left his mark on how writers—artists, surely, but critics, too—go about their craft, mainly by offering the only good metaphor for consciousness we’ve ever had (the stream of consciousness).

It’s James’ emphasis on firsthand experience, I think, that helps give rise to the spirit of participation in journalism—specifically, George Plimpton’s “participatory journalism,” which he applied to sports writing. Want to consider football? Play. Baseball? Play. And so on. At another important juncture, James worried over the “rift” that he sensed science—taken in a very narrow way, as he says—was causing in the world, and this spirit of participation, theoretically applied to ethnography rather journalism, hints at the heart of the thing. Any ethnographer who now hopes to be taken seriously inside the scientific community must retain a particular distance, must remain objective. The scientific methodology to which even Edmundson seems compelled to adhere requires that anthropologists and/or critics reject the very thing James found to be absolutely essential to true understanding.

III.

James died 100 years ago this month—but it didn’t take that long for Freud to displace James in the psychological pantheon. Indeed, it arguably happened during James’ lifetime, and with his knowledge. James has waned, but he has not disappeared. He may even be waxing anew. Ironically, James’ methodology now plays “id” to the “superego” of Freud. More and more, all kinds of writers, critics, journalists, and scientists are returning to James’ participatory spirit, striving to fathom emotions by experiencing them. And does the old superego strategy fare? Considering Goth teenagers, Edmundson says, “The kids look like stylized dungeon escapees, which is pretty much the point. Those who’ve been well pierced and tattooed are hardly ready for life in the glass box . . . or will find much revelation in . . . Sense and Sensibility.”

Perhaps if he’d sought to divine the dictates of the emotion he hoped to describe, Edmundson would have seen Pride and Prejudice and Zombies rising from the grave.

William James, RIP.

Monday, August 23rd, 2010

Welcome to William James Week

On August 26, 1910, William James died at the age of 68. To mark the centenary of his death, this week on The Second Pass will be devoted to James.

On August 26, 1910, William James died at the age of 68. To mark the centenary of his death, this week on The Second Pass will be devoted to James.

I read The Varieties of Religious Experience for the first time about four years ago, and I quickly became a James fanatic. In short order, I read several other books by or about him, some of which will be mentioned on the site throughout the week. Also in store: an excerpt from one of James’ best-known works will go up on the Backlist momentarily; a review of a biography of James’ wife will be published in Circulating; the Shelf will fill up with books related to James; and there will be guest posts on the blog by several very smart people who, like me, hold James dear. I’ve found since discovering his work for myself that fellow fans share my affection for him, my sense that he is almost a real friend — a remarkable feeling to have for any author, much less one who has been gone for a century. If you’re unacquainted with James, I hope that this week on the site will give you a sense of why that affection exists, and will motivate you to learn more about him. If you are acquainted, I hope you get something new from this effort and find it an appropriate tribute.

As always, thanks for reading.

Friday, August 20th, 2010

Soon You Will Be Legally Obligated to Buy a Novel by James Patterson

This list at Forbes of the 10 highest-paid authors over the past year is unsurprising. James Patterson, Stephenie Meyer, John Grisham, etc. JK Rowling is just getting by on the residual wizardry ($10 million), but she better write something else soon.

What’s shocking is the following: “One out of every 17 novels bought in the U.S. are authored by Patterson.” Wow. That’s almost more dispiriting than straight-up illiteracy stats. Plus, this: Stephen King is working on a musical with John Mellencamp.

But as Sarah Crown pointed out on Twitter, the “real news” is Dean Koontz’s hair, which gives Blagojevich a run for his money.

Wednesday, August 18th, 2010

Frank Kermode Dead at 90

Preeminent literary critic, essayist, and academic Frank Kermode has died at 90. In a thorough obituary for the Guardian, John Mullan writes, “His fusing of scholarly disinterestedness and live intellectual curiosity was hard and rare. It made him the leading literary critic of his generation.” From the same obituary:

Preeminent literary critic, essayist, and academic Frank Kermode has died at 90. In a thorough obituary for the Guardian, John Mullan writes, “His fusing of scholarly disinterestedness and live intellectual curiosity was hard and rare. It made him the leading literary critic of his generation.” From the same obituary:

The title of another collection of essays from his post-Cambridge period, An Appetite for Poetry (1989), reflected a new emphasis in Kermode’s thinking about literary criticism and the teaching of literature. He had become surer and surer that literary theory, which he had once invited into the seminar room, was strangling the understanding and love of literature. He had come to think that many university teachers and leading critics of literature, particularly in America, had no “appetite for poetry.” Earlier works from the 80s, Forms of Attention (1985) and History and Value (1988), had explored the need for a literary canon – a core of especially valuable works of the imagination to which we can keep returning. Now he believed that theory, frozen into formula, was the addiction of academic critics “who seem largely to have lost interest in literature as such.” Thus, a final irony: a man who had been one of the country’s leading literary theorists became a scathing critic – sometimes satirist – of literary theory’s self-importance.

(Photo of Kermode by Eamonn McCabe for the Guardian)

Tuesday, August 17th, 2010

In the Ether

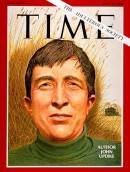

At The Millions, Craig Fehrman presents the history of authors on the cover of Time magazine, in honor of Jonathan Franzen’s appearance this week. It does seem like a (very broad) argument for the decline of the author in pop culture: Just five have been on the cover since Bill Clinton took office. You’ve got to hand it to Time, though — more than three years before Miami Vice premiered, they had John Irving doing a pretty decent Sonny Crockett impersonation. . . . If you think a better title for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein would have been A Zombie Learns French, then this site is for you. . . . Lewis Lapham gets big points for this: “I’m extremely fond of Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me. I love Car Talk.” . . . This 2007 piece about writers and the fonts they love is making the rounds again. (Caleb Crain: “My goal has always been a legible font with a neutral personality, as appropriate to flower arranging as to triple homicides.”) Several prefer Courier or Courier New. I’m a Georgia guy myself these days. . . . A snazzy proposed cover for the screenplay of Reservoir Dogs. . . . If you’re in New York and looking something to do on Friday night, the online literary journal Open Letters will have a reading at Housing Works to celebrate the recent publication of an anthology of the site’s writing.

At The Millions, Craig Fehrman presents the history of authors on the cover of Time magazine, in honor of Jonathan Franzen’s appearance this week. It does seem like a (very broad) argument for the decline of the author in pop culture: Just five have been on the cover since Bill Clinton took office. You’ve got to hand it to Time, though — more than three years before Miami Vice premiered, they had John Irving doing a pretty decent Sonny Crockett impersonation. . . . If you think a better title for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein would have been A Zombie Learns French, then this site is for you. . . . Lewis Lapham gets big points for this: “I’m extremely fond of Wait Wait…Don’t Tell Me. I love Car Talk.” . . . This 2007 piece about writers and the fonts they love is making the rounds again. (Caleb Crain: “My goal has always been a legible font with a neutral personality, as appropriate to flower arranging as to triple homicides.”) Several prefer Courier or Courier New. I’m a Georgia guy myself these days. . . . A snazzy proposed cover for the screenplay of Reservoir Dogs. . . . If you’re in New York and looking something to do on Friday night, the online literary journal Open Letters will have a reading at Housing Works to celebrate the recent publication of an anthology of the site’s writing.

Monday, August 16th, 2010

How Writing is Like Boxing, Maybe

This Missouri Review interview with George Saunders is evidently from back in 2001, but it’s full of timeless humor, general good nature, and thoughts about the writing (and teaching-of-writing) process. Two tidbits here, but make time for the whole thing:

This Missouri Review interview with George Saunders is evidently from back in 2001, but it’s full of timeless humor, general good nature, and thoughts about the writing (and teaching-of-writing) process. Two tidbits here, but make time for the whole thing:

In my work, and in my psyche, there’s this very sentimental, traditional, conventional side that’s always in argument with a more radical, sarcastic side. Some of my stories are really sentimental, but they’re layered over with weird, satirical stuff. For example, “Sea Oak” is a very straightforward story about the haves and the have-nots, about one of the have-nots saying, “Why didn’t I get anything?” To get away with what could be a saccharine, sentimental arc, I cover it with all this dark, perverse stuff that makes the reader mistake me for a scatological cynic.

And: