Reviewed:

Reviewed:

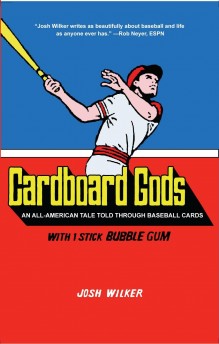

Cardboard Gods by Josh Wilker

Seven Footer Press, 243 pp., $24.95

I was going to write a review of Josh Wilker’s Cardboard Gods, but then realized it would be much more fun to share my thoughts about it with my good friend and fellow baseball nut Jon Fasman. Thus, the following exchange:

From: John Williams

Jon,

Josh Wilker’s memoir tells the story of his life through his baseball card collection. The short chapters (60, by my count) are each pegged to a specific card. Going through the cards with Wilker in relatively quick succession is not unlike dreamily flipping through an old box of lost gems in the attic. Before you know it, you’ve whiled away a few hours. The book was born from Wilker’s blog of the same name, and this is a case where I think that transition was (mostly) a smooth and even useful one. It helps that Wilker has a story, and a voice with which to tell it. The story is of an unconventional upbringing and a lifelong struggle with feelings of what I would call depression. The voice is a nostalgic, sentimental, sometimes (but not often enough for my taste) wickedly funny one that seems both appropriate for baseball and very much of our generation.

With (half-hearted) apologies for sounding like a crank, I feel bad for kids who grew up with the game after we did, who know it (and all sports, really) as a slicker, media-saturated, muscle-bound industrial complex — to say nothing of the cards themselves, which had their special qualities gentrified out of them by proliferating subsets, over-thought production values, and increasing expense. For us, the joy of collecting cards was partly, yes, the thrill of finding a star in a pack — Rickey Henderson, Don Mattingly, Dwight Gooden, etc. (Gooden’s 1984 Topps “Traded Set” card was my most prized possession at age 10) — but also the goofy pleasures of Oscar Gamble’s afro, Bobby Grich’s mustache, and the bovine figures of sluggers like Steve Balboni and Greg Luzinski. And even beyond that, there were the game’s true schlubs — or at least, players whose names and images made it easy to think of them that way: Butch Wynegar; Rance Mulliniks; the Iorg brothers, Garth and Dane. Wilker gets at this love of the misfit when he writes about a bit player named Eddie Leon:

I needed gods with warning-track power, gods with waning speed, gods who drifted from team to team, gods who got released, gods who got sent down, gods who waited and waited and never got recalled. [. . .]

I needed Eddie Leon. I needed a guy posing in a Chicago White Sox uniform while the crooked, cut-off, erroneous card he is posing on identifies him as a member of the St. Louis Cardinals and the back of the card declares he is neither a White Sox nor a Cardinal but a New York Yankee. The back-of-the-card scripture also points out that he “has been among Chisox’ leaders in Sacrifices in ’73 & ’74.”

Among the leaders. On a single team. In bunts. I don’t know how you could say any less about someone without saying nothing at all.

I started collecting baseball cards in 1980, four years after Wilker. (He’s in his 40s, so he had a natural jump on me. I’m 36.) I know you started around the same time as me. But Wilker goes up through 1981, and the cards he features from 1977-79 are familiar to me, having lingered long enough in hobby stores and convention tables to bleed into the edges of my collection. Whatever its flaws — and we’ll get to those — I find it hard to imagine a book more perfectly suited to our generation of baseball fans than Cardboard Gods. Do you agree? And what do you make of that unconventional upbringing, which I’ll leave to you to sketch for our readers?

*****

From: Jon Fasman

John,

At the risk of joining you in Crankland, I think you nailed precisely what makes this book so lovable to people our age. It is a valentine to a certain kind of goofiness in baseball and in baseball-card collecting that has vanished from both. I know everyone wants to think things were simpler and purer in their youths, but in the case of baseball cards, it happens to be true. Something changed during the time we collected. The boom market in the mid 1980s turned a hobby into an investment. I threw my first cards haphazardly into cardboard boxes; by the end I was putting them in plastic sleeves, the thicker the better. I think you and I collected more or less contemporaneously (I began in 1981 and was pretty much done by 1992), and a bit after Wilker’s heyday, but the important thing was that we were hooked before Beckett put a price on everything.

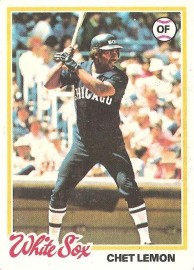

Plenty of things in this book raised a smile (only one thing raised a laugh that knocked me out of my seat, and that was the picture of the Reuschel brothers and Wilker’s perfect description of them as “stunned, doughy, beady-eyed lummoxes glowering apprehensively”—yes, it’s not terribly nice, but on the other hand both of them got to pitch in the big leagues so comparatively they’re ahead of us). But I especially loved this: “Bake McBride is one of those names that I’ll never be able to say without feeling a flicker of happiness. There are others. Oscar Gamble, Jim Bibby. Dick Pole, Pete LaCock. Mario Mendoza, Mario Guerrero, Bob Apodaca, Biff Pocoroba. Cesar Cedeno and Sixto Lezcano and Omar Moreno and Mark Lemongello.” You cited Wynegar, Mulliniks, and the Iorg brothers, a few of my favorites from our childhood era. I don’t want to turn this dialogue into competing lists, but I can’t imagine another time in my life when it might be useful to admit that precious memory space is given over to Al Bumbry, Moose Haas, Lenn Sakata, Chet Lemon, and Shooty Babitt.

Plenty of things in this book raised a smile (only one thing raised a laugh that knocked me out of my seat, and that was the picture of the Reuschel brothers and Wilker’s perfect description of them as “stunned, doughy, beady-eyed lummoxes glowering apprehensively”—yes, it’s not terribly nice, but on the other hand both of them got to pitch in the big leagues so comparatively they’re ahead of us). But I especially loved this: “Bake McBride is one of those names that I’ll never be able to say without feeling a flicker of happiness. There are others. Oscar Gamble, Jim Bibby. Dick Pole, Pete LaCock. Mario Mendoza, Mario Guerrero, Bob Apodaca, Biff Pocoroba. Cesar Cedeno and Sixto Lezcano and Omar Moreno and Mark Lemongello.” You cited Wynegar, Mulliniks, and the Iorg brothers, a few of my favorites from our childhood era. I don’t want to turn this dialogue into competing lists, but I can’t imagine another time in my life when it might be useful to admit that precious memory space is given over to Al Bumbry, Moose Haas, Lenn Sakata, Chet Lemon, and Shooty Babitt.

Of course, players with silly names exist today, but I can’t summon any just now, and I certainly don’t know what they look like, but every one of those guys in the paragraph above—except Mark Lemongello and Omar Moreno (was he a Tiger?)—have their place in my mind. I remember the first person to buy me a pack of cards—a friend of my dad’s who died of cancer a couple of years ago. I remember where I used to look at them—under a desk I no longer have in a house that was long ago sold that belonged to two people who are no longer married.

That is the stuff of routine loss, and all things considered, though I was never a terribly happy kid, I had a perfectly happy, uneventful childhood. Wilker had it rougher. With three hippie parents (a mother, a father, and the mother’s sometime-beau), a strained relationship with his older brother, and an apparently permanent sense of drift, he limps awkwardly from childhood to adolescence into adulthood. At times he can seem a little self-pitying, and at times the book’s prose turns from tolerably mauve to deep purple, but he is funny, perceptive, and likable enough to keep things moving, and to make you (me, anyway) want to stick with him.

Still, is it wrong to admit that I liked the stuff about baseball cards better than the stuff about his family? And is the game really different today than it was when we—all three of us—were growing up, or is that false perspective?

*****

From: John Williams

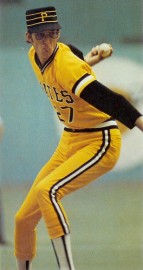

Moreno was primarily a Pirate, but spent some time with other teams, including the Yankees, toward the end of his career. (I fact-checked that, but I knew it off the top of my head. This is what I was absorbing as a kid, instead of a second language.)

You’re right, it’s tempting to just make this a set of dueling lists. But we’ve exchanged those enough over the years. So I’ll just say this before moving on: Roy Smalley.

Amos Otis.

OK, moving on for real: I’m still a big baseball fan, as you know, but like all sports I think it’s become, for lack of a more literary term, grosser over the years. The money, the steroids, the expanded playoffs, the influence of TV, the worsening of both the surly stars and the holier-than-thou media, Bud Selig, etc. The usual (but real) complaints. To apply this to the subjects of Wilker’s book, think of what the age of steroids (and just better conditioning, generally) has done to the nerd in baseball. Even someone like Dustin Pedroia, the Red Sox’ second baseman and one of the more diminutive players in the league, looks somehow buff. No more do we see someone like Kent Tekulve (pictured below, at left), the relief pitcher who succeeded despite, as Wilker writes, his “thick glasses and bulging Adam’s apple and mathematician wrists and ungainly, unmanly submarine delivery.”

About the Kent Tekulves of the world, Wilker is terrific. You’re right, though, that his prose can veer toward the almost mystic. Early on, he writes: “When I try to identify my first baseball card, I see my brother, and I see this 1974 Topps Cleon Jones. I hold it and feel something twitching, beating, like wings.” He later writes a mini-essay about benchwarmer Luis Gomez that starts, “Is life a battle between good and evil or an inconsequential rest stop between oblivions?” What follows could very well be meant as pure parody, though if it is, I wish the intention was clearer.

About the Kent Tekulves of the world, Wilker is terrific. You’re right, though, that his prose can veer toward the almost mystic. Early on, he writes: “When I try to identify my first baseball card, I see my brother, and I see this 1974 Topps Cleon Jones. I hold it and feel something twitching, beating, like wings.” He later writes a mini-essay about benchwarmer Luis Gomez that starts, “Is life a battle between good and evil or an inconsequential rest stop between oblivions?” What follows could very well be meant as pure parody, though if it is, I wish the intention was clearer.

But I give him more leeway when he’s writing in soft focus about his family. Even when he calls on a cozy baseball metaphor, as in the passage below about his dad, I find it mostly affecting. At this point, his dad is living in New York, working and providing for his wife and kids while Wilker’s mom lives in the family’s home with her boyfriend Tom:

There were never any signs that [my father] had a social life. During each of the yearly visits Ian and I made to see him in New York, there would always come a moment when he’d stare at us across the table of a Bun-N-Burger or Chock Full o’ Nuts.

“How’s your mom?” he would ask.

On some level I understood he was waiting for her, like an aging veteran who’d been demoted to the minors, hoping in spite of his ballooning ERA and diminishing innings for the call from the big club once again.

I’ll leave you with two thoughts: The first is that you’re a liar, even if inadvertently, because you said the book only raised one laugh that sent you from your seat. I refuse to believe you weren’t also ejected by the chapter on pitcher Dock Ellis, who famously threw a no-hitter while under the lingering influence of LSD. I’m thinking particularly of his attitude toward the Cincinnati Reds, which I won’t spoil for readers but was one of the funniest things I’ve read in any book. I suppose the credit for this laugh goes to Ellis, strictly speaking, but I thought Wilker presented it perfectly.

The second thought: It strikes me that the book most resoundingly succeeds — or fails, depending on how you look at it — by erecting a pretty firm barrier against non-collectors. This is not a book that will appeal to someone with no experience of these cards whatsoever. It’s not a book that will draw someone in through the subject matter but really have universal appeal. Am I wrong about that? And is that a credit to Wilker’s writing, or a strike against it? Or both?

Thanks for taking the time to swap e-mails about this. Sorry about your Cubs this year. And at the risk of alienating a large portion of my site’s readership: Go Yankees.

*****

From: Jon Fasman

Oh, lord. OK. Ron Hassey and Andre Thornton. Bob Dernier, Larry Herndon, Richie Zisk. But now I’m done; I’m done.

“Grosser” is a good way to put what’s happened to baseball over the past, say, thirty years. Everything has grown bigger: players, their salaries, the cost of stadiums, the length of games, and the amount of knowledge available to even a casual fan. (An aside on the subject of a players’ physical size: I remember at the Phillies game you and I attended a few years ago, Jimmy Rollins looked freakishly small during batting and fielding practice next to the other players—I mean midget small. Come his first at-bat, they put his height and weight on the board: he’s my size, to the inch and pound.)

And it’s this last part, I think, the sheer wealth of knowledge, that makes it difficult to imagine that a troubled, lonely kid today would find baseball cards as totemic as Wilker—or we, I guess—did way back when. That gap between player and fan that cards helped bridge barely exists any more. Information is always available; personal information even more so. It’s like reading the box scores to find out what happened last night. I still do that, but I make a point of it; I do it because that’s what I’m used to and that’s what I prefer doing (and, I hasten to admit, because it’s August and I don’t have a team in contention; if the Cubs looked like they were making a run, I’d purchase the MLBGoogleDroidiBlackberryWii app that shoots box scores directly into your brain so you don’t have to waste time getting the information past your eyes). I have a hard time believing my sons will do the same.

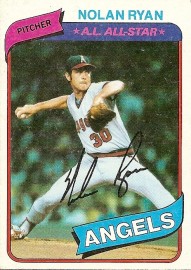

One card-related design fact caught me as I leafed through this book. Although I stopped seriously collecting in the early 1990s, I still buy a pack a year—one baseball and one football. In some respects it’s a comforting constant: the cards are still the same size. They still have largely the same traditional stats on the back—no WHIP and no PECOTA—and follow the same basic design principles on the front: a large picture of a player, along with his name, team name, position, and the card company. In other ways they are radically different: sharper photographs, more active, team logos and trademarks more prominently displayed. There was something charmingly amateurish about the cards and the players on them in Wilker’s book. It was more obviously a game. The better players—Henderson, Nolan Ryan, Ron “Gator” Guidry—had action shots, but the everydayers—the “common cards”—tend overwhelmingly to look like doofuses (except maybe for Harold Baines, who may be the saddest looking person ever to walk the earth). These pictures subtly communicate to the lonely kid who collects (ahem): hey, this joker’s in the major leagues, and look at him. You could do that.

One card-related design fact caught me as I leafed through this book. Although I stopped seriously collecting in the early 1990s, I still buy a pack a year—one baseball and one football. In some respects it’s a comforting constant: the cards are still the same size. They still have largely the same traditional stats on the back—no WHIP and no PECOTA—and follow the same basic design principles on the front: a large picture of a player, along with his name, team name, position, and the card company. In other ways they are radically different: sharper photographs, more active, team logos and trademarks more prominently displayed. There was something charmingly amateurish about the cards and the players on them in Wilker’s book. It was more obviously a game. The better players—Henderson, Nolan Ryan, Ron “Gator” Guidry—had action shots, but the everydayers—the “common cards”—tend overwhelmingly to look like doofuses (except maybe for Harold Baines, who may be the saddest looking person ever to walk the earth). These pictures subtly communicate to the lonely kid who collects (ahem): hey, this joker’s in the major leagues, and look at him. You could do that.

Fortunately, Wilker avoids this sort of mawkishness, or at least he approaches it obliquely. To answer your second question: I think you’re right. I don’t see this book appealing to non-collectors or non-fans, but neither can I see any collector or baseball fan not loving it. It is the story of how adulthood gradually pushes those passions to the side for business that is more important, higher-stakes, more central to the inexorable forward march into the grave, but perhaps not quite as directly fulfilling.

As for the Dock Ellis credit, that goes to you: you read that story to me over the phone before I read the book, so when I laugh it’s at your Dock Ellis impersonation as much as the story itself. Either way, it’s pretty funny. I guess this is where I sum up, but I can’t quite do it; summing up a discussion about baseball cards is no different than summing up my pre-adolescent life. So I’ll leave it at this: Vida Blue. Frank Tanana. John “T-Bone” Shelby, and Manny Trillo.

Jon Fasman is the author of two novels, The Geographer’s Library and The Unpossessed City

, as well as a great deal of journalism. John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.