Reviewed:

Reviewed:

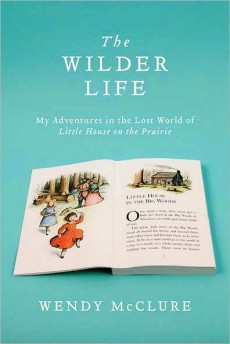

The Wilder Life by Wendy McClure

Riverhead, 352 pp., $25.95

Laura Ingalls Wilder’s series of Little House children’s books is an inspired choice of subject for a gently irreverent nonfiction book. For many people of Wendy McClure’s generation, of which I count myself a member — McClure and I were children in the 1970s, when those books experienced a spike in their popularity — Wilder’s stories, told from her perspective as a young pioneer girl, provided an early literary experience. Many more people knew only the version of Wilder’s world portrayed in the TV show starring Michael Landon that expanded the cast of Wilder’s original work to include, among other additions, townie thugs and a morphine-addicted adopted brother — embellishments that might have been intended to help attract young male viewers. This includes me. I was, until quite recently, one of the “God knows how many people who thought The Little House on the Prairie was just a TV show” of whom McClure writes. The publisher of The Wilder Life seems to have little doubt the books were targeted to girls. The jacket copy describes them as “a series of books that have inspired generations of American women,” and the cover is a bright teal.

There are two kinds of children’s entertainment, the kind that children fanatically seek out — Twilight and Harry Potter come to mind — and the kind forced upon them. I’ve always considered the Little House series a paradigmatic example of the second kind. If I can extrapolate from my own experience, plenty of people who read the books and/or watched the show didn’t quite understand them, or gin to the austere pastoral life they valorized. Watching the show was often like eating a dark green vegetable, or watching a PSA with a big costumes budget, and I’m sure many kids who watched did so simply because they didn’t have control of the family remote (or the dial). There was nothing in the show for a child to aspire to — not the men’s bushy beards or their overalls, not running through tall grass barefoot, certainly not the covered wagons. (This was especially true in my case, as I already lived in Kansas, just 150 miles north of the original Little House.) Perhaps the show was just a particularly austere reminder of the limitations of children’s liberty. As our parents and their peers enjoyed the privileges of young adulthood in the 1970s, we were supposed to relish a fictional world with neither cars nor electricity. Mad Magazine’s 1978 parody of the TV show was titled “Little House Oh, So Dreary.”

As today’s kids discover their own roster of vampires, wimpy kids, and wizards, it’s a good time for a smart journalist to dust off her Little House paperbacks, pull the DVDs from the children’s section of her local library, set out on U.S. 14 — also known as Laura Ingalls Wilder Historic Highway, which connects several Ingalls home sites between Wisconsin and South Dakota — and marvel at stalwart pilgrims snapping photos of each other hunched at the entrance of a replica dugout house or trying on calico aprons in the gift shops. And perhaps also poke some fun at the homey trappings of a cultural birthright that many of us would have preferred to shrug off.

McClure is not the wry, snarky guide you might expect from her generation. She acknowledges that “if you didn’t already know and love the Little House books, they would look and sound an awful lot like something your grandmother would foist upon you as a present, what with their historically edifying qualities and family values — basically, the literary equivalent of long underwear.” But she loved them. There was a brand of young male Star Wars fan who always kept one foot earnestly hovering in space, and as a girl, McClure was the equivalent fan of the Little House series, which offered a portal to a world of “woods and prairies and big sloughs and little towns” that was “as self-contained and mystical as Narnia or Oz,” but also “more permeable.” She not only imagined her way into the Ingalls’ lives, but also dragged Laura into the future, as a time-traveling imaginary best friend who “allowed me to infuse my own world with Laura-like wonder,” as when she took Laura to the North Riverside Mall, where McClure “ushered her onto escalators and helped her operate a soda machine.”

By middle school, McClure’s homesteading fantasies, which included adopting a suckling pig as a pet, had receded — she gives us a portrait of herself as a graduate student who smoked menthol cigarettes and ran up her credit card buying QuikTrip microwave sandwiches — but when she picked up the books again in 2007, in the months after the death of her mother, she experienced an even more fervent desire to commune with Laura, which would only be satisfied by a series of trips into what she calls “Laura World.” (It’s a desire that was presumably intensified by the desire to write a book about her adventures.) So she travels to the author’s Wisconsin birthplace, on Lake Pepin; to the banks of Minnesota’s Plum Creek, the setting for Wilder’s On the Banks of Plum Creek; and to the Missouri home where Wilder began writing not as a bemused observer, but as a pilgrim.

There are shades in McClure’s book of the travel writing genre that might be called “Bewildered Urbanite at the State Fair.” The Christian survivalists she encounters at Homesteading Weekend at Clover Meadow Farm in Northern Illinois exasperate her, and she recoils from the tackiest of tourist attractions, life-sized “soft-sculptures” of the entire Ingalls family in the parlor of Masters Hotel in Burr Oak, Iowa. McClure has an eye for visual details that evoke the inevitable disappointment of meeting her favorite children’s series in the real world, such as the “denim shirt with an embroidered Little House on the Prairie logo on it” worn by the manager of the Little House on the Prairie Museum.

Ultimately, the book is too sweet — or cautious — to fit neatly into the bewildered urbanite category. It’s missing the kind of thick description — of, say, the upholstery of small-town diners, the knick-knacks for sale, or even her fellow pilgrims — that would put it among the form’s finer examples. It’s possible that George Saunders has ruined me for any other writing about Americana tourism, but I could not help thinking that The Wilder Life wasn’t as bitingly funny as it could have been.

It’s also not a simple fan’s guide — the product of a blindered obsession. It might be irresponsible for a reviewer to wish for another thing a book could have been, but I caught myself wanting this one to be more than a breezy travelogue with thin historical padding. I wanted McClure to spend more significant time with some of the series’ deeply committed followers she learns about or meets: Barbara Walker, whose recipes for a hundred dishes mentioned in the series, from codfish balls and vinegar pie to pancake men and corn dodgers, are published in her 1989 Little House Cookbook; the family of seven from Houston whose younger children study under a home school curriculum inspired by the series, in which they see “faith running throughout”; the producers of the Japanese anime series Laura, a Girl of the Prairie; the man named Lorenzo who planned in 2004 to rebuild the set of the Little House TV series, and then host a blowout dance party on it; the man who started a religion called “Lauraism” and ran for mayor of Minneapolis; or Ann Romines, a Willa Cather scholar who writes in Constructing the Little House: Gender, Culture and Laura Ingalls Wilder of Wilder’s “explosive critique of the language offered by her culture.” But we’re only offered fleeting, if entertaining, glances.

Surely, the question of what about the series seems to foster the projections of groups as disparate as the Hmong settlers of Walnut Grove, Minnesota, some of whom say the fictional Walnut Grove of the television series drew them there, and Slovenian visitors to the Wilder Museum in Mansfield, Missouri, where they can find Slovenian translations of the Little House book, deserves a book-length answer. McClure, an editor of children’s books, is professionally equipped to place the series in the larger context of American children’s literature, but she doesn’t quite do that either.

McClure’s tone did grow on me as I began to recognize her true theme — the ungainliness of searching after lost worlds, both the unspoiled world of the 19th century plains depicted in Wilder’s books and the world — less distant but faded — in which a generation of young girls (and some boys) read them. In certain moments, like the morning she stares across the expanse of a frozen Lake Pepin, which the Ingalls family once crossed in similar conditions, and convinces herself that “if we went across we would follow them,” McClure truly conjures Laura World. More often, she wobbles on the surface of the present, as when she checks her email on her white MacBook at a South Dakota coffeehouse directly across from the field where Pa had once “twisted hay into sticks” and “shaken his cold-stiffened clenched fist and raged at the keening wind,” or when thunderclaps and hail smashing against the fiberglass top of the sleeper covered wagon she and her husband have rented awaken her, and she longs for late-night television and scotch.

In Walnut Grove, she meets two scruffily dressed sisters, the elder wearing a “crumpled white button-down shirt,” the younger a black T-shirt that had said “Farmer Girl,” McClure guesses, before the rhinestone letters spelling out the second word wore off, who tell her they will compete in a Laura Ingalls look-alike contest at the next day’s Wilder pageant. Eager to make a connection, McClure asks, “Are you going to get all dressed up in your prairie clothes?” The girls exchange a look before the elder sister answers, “Well, we already are.”

To find a girl whose enthusiasm for Little House matches her own, McClure has to go to Chicago’s American Girl Place, a showcase for the popular American Girl dolls. There she meets Julie, who keeps on her bedroom rug a boxed set of paperbacks with blue covers just like McClure’s own (and a copy of By the Shores of Silver Lake open on her chair). Julie is American Girl’s 1970s doll.

Michael Rymer writes about education for the Village Voice and about books for Coldfront Magazine He lives in the Bronx.

Mentioned in this review:

The Wilder Life

The Complete Little House Nine-Book Set

Little House on the Prairie (TV)