Discussed:

Discussed:

Retromania by Simon Reynolds

Faber & Faber, 496 pp., $18.00

Simon Reynolds’ Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past is that rare thing, a brainy joyride. Ostensibly a book about a trend—popular music’s cannibalization of itself—it ends up being a good excuse for Reynolds to excavate his vast knowledge of popular music throughout history and address some of the most compelling questions surrounding culture a decade into the 21st century: Is YouTube an invaluable archive or an unnavigable “anarchive”? Are Japanese kids who mimic punk to the last detail somehow more authentic than the original punks? What does the nostalgic taste of hipsters have in common with the global economy? Why has popular music felt stalled for so long? Has the very idea of the future lost its pull?

Along with his encyclopedic music brain, Reynolds brings an accessible but intellectual style that draws on a broad range of cultural artifacts and authorities—a random sampling of index entries accurately reflects the array: Adam Ant, Harold Bloom, Can, Phil Collins, John Coltrane, Sigmund Freud, Gossip Girl, Cary Grant, The Jesus and Mary Chain… It also pointed me to about a thousand blogs, videos, records, and books to investigate.

One of the things I found most interesting about Retromania, in an age of polemic, was its underlying sense of struggle. Reynolds is a collector himself, an archivist of sorts, and I often felt—even coming from a writer who was deeply committed to rave culture when it was all the rage, and who argues for the value of always looking forward—an internal battle between the frontier of the new and the tug of the old. I asked him about this and other subjects over e-mail, and he responded at length—about everything from how Harry Connick Jr. is like Adele to gadgets becoming bigger stars than rock bands to Nick Hornby’s feelings about the Beatles to three obscure music books he strongly recommends:

You quote Miriam Linna, the original drummer of the Cramps, talking about her enthusiasm for “old records that were new to us.” That struck me for a variety of reasons, not least because I’m 37 and this happened quite a lot with me. There are all kinds of things I came to a little late (early R.E.M.) or very late (Motown, the Beatles), just by the accident of when I was born. And you say the past is always going to have more and better stuff than the present—it’s just math. So as the past keeps piling up, how do you/we avoid the temptation to just look backward for the best stuff? (Similarly, you write, “What makes actual young people stop chasing tomorrow’s music today . . . and pursue yesterday’s music today?” Back to the accident of timing—couldn’t this just be because there are periods when tomorrow’s music doesn’t seem as promising, or simply as good, as yesterday’s music?)

Well, in many ways I can see why young people of the current era would want to listen to a lot of older music. It’s great music. And often it’s great in a way that is also relatively accessible and simply enjoyable. It could be that the majority of the most straightforwardly pleasing melodies and riffs were reached relatively early in rock’s history. (One of the problems if you follow the innovation imperative as a musician is that increasingly the only ways forward involve getting more convoluted, abstruse, abstract, inclement to the ear.) At any rate, there is a lot of great music piled up behind us, and the present increasingly has its work cut out if it wants to compete. I find this as a radio consumer: now that I live in Los Angeles, I’m listening to the radio way more than I did in New York, because we’re in the car so much, and it’s much more fun to shuttle between radio stations than put on CDs or plug in the iPod. I’ll tune in to KCRW, which is the NPR station that invented the “Morning Becomes Eclectic” template and which plays a lot of cool new music, but after a while I’ll find myself drawn to the classic rock stations or a “shuffle”-style station like Jack FM, because they have bigger reserves of great tunes to draw on, they have the Sixties, Seventies, Eighties at their disposal, so they can out-gun the present. Same thing happens listening to the Top 40 pop stations—superfun in short bursts; my kids love Ke$ha and B.E.P.—but after a while, the homogeneity of all that pop-trance-R&B-rap gets wearing, and so it’s back to classic rock. If I was 17 and faced either with the KCRW-style modern post-indie, which can get a bit prissy, or this bombastic club music on Top 40, I can easily feel the pull of the older music. There’s so much great stuff from that era, and it has a certain musicality, a hand-played quality, a freewheeling energy, that is absent in modern radio rock. It has the romance of rock’s storied glory days. And apparently that’s what a lot of young high school and college-age kids listen to 70 percent of the time: their parents’ music. There’s a lot of listening to Beatles and Led Zeppelin going on.

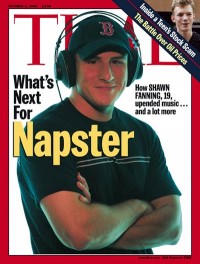

You quote Bill Flanagan saying, “musical trends are now shaped more by delivery systems than by any act,” and elsewhere you cite Eric Harvey of Pitchfork, who said the 2000s might be “the first decade of pop music . . . remembered by history for its musical technology rather than the actual music itself.” Then you write, “Napster Soulseek Limewire Gnutella iPod YouTube Last.fm Pandora MySpace Spotify . . . these super-brands took the place of super-bands such as Beatles Stones Who Dylan Zeppelin Bowie Sex Pistols Guns N’ Roses Nirvana . . .” Do you think this is a permanent new state of things? I sometimes fear that it is. In fact, I think technology is so tied to people’s idea of the future—and ultimately, I can’t get excited about e-readers if there’s nothing good to read, etc.—that I’m almost grateful for some level of retromania if it means looking back to a time when the artists’ names meant more than the tech names. What’s to become of the human element in music and art, for better or worse? Or is that just a question that betrays my irrational fear of the future?

You quote Bill Flanagan saying, “musical trends are now shaped more by delivery systems than by any act,” and elsewhere you cite Eric Harvey of Pitchfork, who said the 2000s might be “the first decade of pop music . . . remembered by history for its musical technology rather than the actual music itself.” Then you write, “Napster Soulseek Limewire Gnutella iPod YouTube Last.fm Pandora MySpace Spotify . . . these super-brands took the place of super-bands such as Beatles Stones Who Dylan Zeppelin Bowie Sex Pistols Guns N’ Roses Nirvana . . .” Do you think this is a permanent new state of things? I sometimes fear that it is. In fact, I think technology is so tied to people’s idea of the future—and ultimately, I can’t get excited about e-readers if there’s nothing good to read, etc.—that I’m almost grateful for some level of retromania if it means looking back to a time when the artists’ names meant more than the tech names. What’s to become of the human element in music and art, for better or worse? Or is that just a question that betrays my irrational fear of the future?

I do think that technology somehow sucked up and monopolized all the excitement-energy of fans during the Noughties—the playback devices, the digital platforms, the online communities, etc., simply displaced music as the focus of fandom to a large extent. And particularly in the sense you refer to of the technology having that future-buzz aura. Someone, I can’t remember who now, wrote a piece this year about how Apple was supplying a kind of religiosity with the way that their products have an aura of transcendence and superhuman perfection, a sort of tangible, everyday miraculousness. My son Kieran is excited by new stuff to do with computers and games in the way that people of my generation were excited by new groups or musical movements. I was a fanatic for science fiction; you could argue that he and his generation are grappling with the stuff of science fiction on a daily basis. At the same time, Kieran has been affected by retromania: he’s really into vintage games, or digitally simulated versions of 8-bit games, and he enthuses about their clunkiness and old-fashioned qualities. He is 11, and words like retro and vintage are part of his vocabulary.

I’ve no idea where all this is going or whether it will shift drastically in another direction at some point. It does seem like some kind of mass disenchantment with digiculture is brewing, a sense that it isn’t really making people happy, and that convenience isn’t actually that life-enhancing.

What do you see as the difference, if any, between “preservation as a cultural ideal” and/or “re-enactment art,” as you call it, and simply working within an old form? At what point does working in an old form become a counterproductive act of nostalgia?

I’m not sure I have a problem with people who embrace an out-of-date style of music, master its craft, and put it out there for whoever cares to hear it. Whether it’s people who’ve learned to play bluegrass (these days more likely to be middle class folk from anywhere in America other than the South, and in some cases from outside America altogether, as with Mumford & Sons), or a group of people getting together to play brass band music or Early Music. I don’t know if nostalgia comes into it much: modern bluegrass outfits don’t have any personal memories of that music’s golden ages, nor do they wish they could go back to live as a hillbilly. It’s just a style of music they like. I don’t share or particularly understand the impulse at work, but it’s no more troubling to me than someone who painstakingly teaches himself how to do old-fashioned engraving or any other bygone craft. There might be a preservation aspect to the motive, “let’s keep this skill, this way of doing things, alive,” but mostly I think it’s done because certain approaches—whether it’s using a letterpress or playing a banjo—produce effects that the practitioner prefers aesthetically. Also, the difficulty of mastering these skills is part of the attraction, in contrast to the ethos of convenience and facilitation that presides in digital culture.

I do tend to think of deliberately cultivated old-timey styles as belonging to the domain of “hobbies” or pastimes, though. Whereas pop and rock can be, and have been, “interventions in the battlefield of culture.” If you put all your energy as a performer or a listener into a style of music that is out-of-time, then you are absenting yourself from the terrain of popular culture as it’s hitherto been known. Of course, now and again something bygone gets to be commercially successful: Harry Connick Jr., or, indeed, Mumford & Sons.

Re-enactment is something quite different. It’s an art world practice that is bound up with the philosophical notion of the Event, toward which it has a paradoxical relationship. The artist re-enactment, whether it is of a political conflict or a mythical moment in rock history, is a non-event, an anti-event, it belongs to the “dead time” of repetition and simulation. But it is also a ghost version of the original event, haunted by History, deriving its spectral resonance from reference back to a rupture in time that it can never really replicate.

You say, “Part of the problem is that the musical landscape has grown cluttered. Most of the styles of music and subcultures that have ever existed are still with us. From Goth to drums’n’bass, metal to trance, house to industrial, these genres are permanent fixtures on the menu, drawing new recruits every year. Nothing seems to wither and die. This hampers the emergence of new things.” Does it hamper it, or is it just that there’s a finite number of new things, of new variations? I think about this with writing and books a lot, whether anything radically new is even possible. I mean, occasionally Jonathan Safran Foer will take a pair of scissors to an old novel or something, and that might be an interesting one-off, but is there anything left (in writing, music) that could be a firm foundation for widespread work?

It might indeed be finite, a depressing prospect! I tend to think that humans are infinitely ingenious, though, and it seems unlikely that there are no more new musical ideas or sounds to be discovered. New machines will be invented, surely. One of the problems with pop/rock is that it’s relatively easy-access as a genre, so multitudes of people can have a go at it and produce decent results. So there’s a hell of a lot of repetition and redundancy, minor differentiation, and then you also get this mad race of droves of people competing to find something that sets them apart or takes the music a little further in whatever direction they’re looking at. Hence the great sense of congestion within genres (particularly genres like dance and metal, but all of the genres, really), and of profusion as these genres diverge and splinter and subdivide. It’s like music started as a white page of virgin possibility and everybody has scribbled lines across it, and then lines within the lines. In the year 2011, there’s so much ink on the page that it’s almost black. There’s hardly any white space left.

Of course, the other fluke thing about popular culture was that it was able to maintain for a really long time a significant overlap between the popular and the sonically forward-looking. Maybe that simply wasn’t sustainable indefinitely. The parallel with writing would be the fact that there’s hardly any readership for experimental fiction. The intelligent audience for novels will only go so far away from stuff like plot, character, readability. It’s probably similar for the intelligent audience for music: it will only go so far away from songs, tunes, steadiness of structure and rhythm, etc.

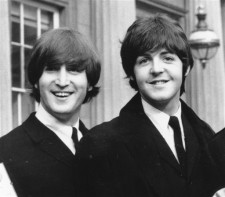

Pardon me for presuming, but I have a feeling you’ll hate this quote. But I’m very interested to hear your take on it. Nick Hornby, writing about Ben Folds, said: “…he is working in a medium (loosely, pop/rock) that at the time of writing—and, let’s face it, at the time of reading, unless you’re reading this in 1970—is widely regarded as washed-up, exhausted, finished. So his songs are just songs. . . . There is an argument which says that pop music, like the novel, has found its ideal form, and in the case of pop music it’s the three- or four-minute verse/chorus/verse song. And, if this is the case, then we must learn the critical language which allows us to sort out the good from the bad, the banal from the clever, the fresh from the stale; if we simply sit around waiting for the next punk movement to come along, then we will be telling our best songwriters that what they do is worthless, and they will become marginalized. The next Lennon and McCartney are probably already with us; it’s just that they won’t turn out to be bigger than Jesus. They’ll merely be turning out songs as good as ‘Norwegian Wood’ and ‘Hey Jude,’ and I can live with that.”

True? Insane? Both? Discuss.

That’s the “there’s only eight notes in an octave” argument. . . . I don’t hate this idea, just find it depressing: the idea that a particular artistic mode is finished, in the sense of settled, its scope of possibilities fixed.

What Hornby’s sort of saying, without quite saying it, is that what made Lennon & McCartney the world-historical force they were was not primarily their melodic gifts: it was extraneous factors, extra-musical stuff, without which they’d have been closer to a Burt Bacharach-level phenomenon. What happened was slightly out of their control: they became the channel for the Zeitgeist. But instead of concluding that you should look anywhere else but three-or-four-minute verse/chorus/verse for that extra-musical/Zeitgeist-y impact, maybe even look outside music altogether . . . Hornby says, “stuff the bigger-than-Jesus, world-historical force part, just give me the tunes.” That happens to most music fans as they get older: they stick with the style of music itself, rather than look for a new music that gives them the same feelings they got from that style of music when it first emerged. Which is why late-Seventies punk bands with pot bellies and balding pates are treading the boards all around the world: as with every kind of music, there’s an audience happy to have the substance and forego the spirit.

What Hornby’s sort of saying, without quite saying it, is that what made Lennon & McCartney the world-historical force they were was not primarily their melodic gifts: it was extraneous factors, extra-musical stuff, without which they’d have been closer to a Burt Bacharach-level phenomenon. What happened was slightly out of their control: they became the channel for the Zeitgeist. But instead of concluding that you should look anywhere else but three-or-four-minute verse/chorus/verse for that extra-musical/Zeitgeist-y impact, maybe even look outside music altogether . . . Hornby says, “stuff the bigger-than-Jesus, world-historical force part, just give me the tunes.” That happens to most music fans as they get older: they stick with the style of music itself, rather than look for a new music that gives them the same feelings they got from that style of music when it first emerged. Which is why late-Seventies punk bands with pot bellies and balding pates are treading the boards all around the world: as with every kind of music, there’s an audience happy to have the substance and forego the spirit.

The intriguing idea I take away from this, though, is the thought that retro artists may be drawn to adopt older styles because it’s what the nature of their specific talent dictates: they don’t have any choice about whether they can be out-of-date or up-to-the-minute, there’s this one thing they really excel at. So a singer might just have a particular kind of voice that demands old-fashioned material . . . Maybe that explains Adele. What I don’t understand is why she is considered a major “contemporary” artist, whereas Harry Connick Jr.—who did the exact same thing when he first emerged, in so far as, like Adele, he was plying a style that’s 45 years behind the times—was considered a nostalgia act.

The book is most thoroughly about music, but do you think the retro-manic tendencies you see there apply as well to books, movies, visual art? Or is there an art form you currently admire for its relative lack of obsession with the past?

Music and fashion and graphic design seem to be the areas where retro-consciousness is most intense and prevalent. Obviously, music is the art form I care most about, where these tendencies are most perplexing and alarming for me; I don’t have the same investment in fashion or design. After that, I think you can see a fair amount of retromania in movies, with the remake phenomenon. I was going to write more extensively about movie remakes in Retromania, but I came to the conclusion that there wasn’t that much mystery about the phenomenon, that it was primarily business-driven, in the sense that the studio executives thought it was a good way to get people into theaters. But I should probably have written more about retro-y auteur directors: I have a little bit on Jim Jarmusch but Quentin Tarantino warrants analysis, and there are other directors of that generation, like Todd Haynes, who probably belong in that context. With TV, there’s probably things to be said about specific shows that fetishize period detail: Life on Mars and Ashes To Ashes, Mad Men. But apart from nostalgia-oriented programming, such as repeats, I don’t know if retro-TV really exists as such.

Music and fashion and graphic design seem to be the areas where retro-consciousness is most intense and prevalent. Obviously, music is the art form I care most about, where these tendencies are most perplexing and alarming for me; I don’t have the same investment in fashion or design. After that, I think you can see a fair amount of retromania in movies, with the remake phenomenon. I was going to write more extensively about movie remakes in Retromania, but I came to the conclusion that there wasn’t that much mystery about the phenomenon, that it was primarily business-driven, in the sense that the studio executives thought it was a good way to get people into theaters. But I should probably have written more about retro-y auteur directors: I have a little bit on Jim Jarmusch but Quentin Tarantino warrants analysis, and there are other directors of that generation, like Todd Haynes, who probably belong in that context. With TV, there’s probably things to be said about specific shows that fetishize period detail: Life on Mars and Ashes To Ashes, Mad Men. But apart from nostalgia-oriented programming, such as repeats, I don’t know if retro-TV really exists as such.

The art world seems to be grappling with a lot of the same issues that are explored in the book: topics like the archive, ruins, collective memory, and “hauntology” have been hot during the last decade, and of course I have a section on the re-enactment trend. There is also a lot of fretful debate on the lines of “postmodernism’s dead, but what’s next?” going on in the art world, too.

One area where “retro” doesn’t seem to signify much is in fiction. You don’t really hear about novelists writing in the style of Faulkner or Dickens, or a Mumford & Sons-style throwback movement in poetry based around bringing back the sonnet. Then again, maybe things like this are going on for all I know.

In the early phase of working on the book, I would always be running into people at parties in New York, being asked what I was up to, and then being surprised when they would say that retro was a big thing in whatever their field was. I recall a poet telling me that, “oh yes, we have retro poetry.” It does seem to be a culture-wide paradigm to a great extent.

There are two quotes taken together that fascinated me. First, Karl Lagerfeld: “In 1965, people were still far away from the end of the century, and they had a completely childish, naive vision of what the end of the century would bring.” Later, you quote James Kirby, who said, “2000 was always the future for us. We expected something significant from that year. When it came it was just the same as it ever was except we had no 2000 to look forward to anymore. It could be a psychological post-millennial hangover for us all which will take some time to pass for this generation.” In writing the book, did you get the sense that calendar-driven excitement and anxiety about the future is that strong a factor in human imagination and culture? Is it possible that the next revolutionary moment will arrive in the 2060s or ’70s, when 2100 is looming, or was the millennium a singular inspiration?

There is something about the shift of that single numeral, from a 1 to a 2—from 1999 to 2000—that felt like it should be a movement across a threshold. It’s only a year’s difference, no different than the time that separates 1985 from 1986, but it seemed to have this looming momentousness. I don’t know when it first became a big beckoning yet ominous thing in the culture—probably well before 2001: A Space Odyssey—but I can’t remember a time when there wasn’t that sense of expectation about the 21st century. I was a big science fiction fan as a teenager, so that intensified it, but I think most people felt more or less the same way. Nothing like that exists now, in terms of a date that seems like a precipice. I wonder also if the younger generation even has the same relationship to temporality? The Future doesn’t seem to have the same libidinized aura around it as a concept. Possibly because it seems to promise so much less: there is a real prospect that they’ll be less wealthy than their parents, be living in countries whose infrastructure grows ever more decrepit.

There is something about the shift of that single numeral, from a 1 to a 2—from 1999 to 2000—that felt like it should be a movement across a threshold. It’s only a year’s difference, no different than the time that separates 1985 from 1986, but it seemed to have this looming momentousness. I don’t know when it first became a big beckoning yet ominous thing in the culture—probably well before 2001: A Space Odyssey—but I can’t remember a time when there wasn’t that sense of expectation about the 21st century. I was a big science fiction fan as a teenager, so that intensified it, but I think most people felt more or less the same way. Nothing like that exists now, in terms of a date that seems like a precipice. I wonder also if the younger generation even has the same relationship to temporality? The Future doesn’t seem to have the same libidinized aura around it as a concept. Possibly because it seems to promise so much less: there is a real prospect that they’ll be less wealthy than their parents, be living in countries whose infrastructure grows ever more decrepit.

I loved the profiles of Tim Warren and Billy Childish, which appear fairly close together toward the middle of the book. Warren owns a “specialist garage record store and reissue label,” and lives in a vividly described Brooklyn apartment/stock room. Childish is “Britain’s leading exponent of retro-punk and probably the biggest single influence on the second wave of garage revivalism that crossed over into the mainstream in the early 2000s with bands like The White Stripes and The Hives.” Childish, in particular, says some sharp things about his love of old music and recording techniques. Where do you overlap with them in terms of your love for collecting and for some old music, and where do they lose you?

I was totally into the Sixties garage punk stuff that Tim Warren has dedicated his life to, and actually bought one of the Back from the Grave compilations he put out during my early-Eighties garage phase. But I could never make that totally fanatical “this is the only music for me” identification that he made, because I’m too curious about other kinds of music and I do have that kind of almost ethical drive to look for things to love in the present and for things that seem to point to the future. I prefer American garage punk to the kind of music that Billy Childish’s aesthetic is based around, but I’ve enjoyed some of his music and appreciate the spirit behind it. I admire his commitment and how eloquently he articulates it as a credo. A lot of what he talks about in terms of restriction being liberating for artists makes sense. It’s an idea that other musicians like Holger Czukay and Brian Eno have also voiced.

Even at my most future-oriented, as with during the rave days, I would still be investigating older music. During the period when I was going down to London jungle stores every week to pick up the latest tracks, I was also buying or taping off other people loads of Krautrock, Seventies progressive music, musique concrete, you name it. But I actually didn’t have time to listen to most of these tapes more than once or twice, because I was so obsessed with taping transmissions from the rave pirate stations. And I think that was healthy, really. Harry Smith, the guy behind The Anthology of American Folk Music, actually said something to this effect: “Any kind of popular trend is infinitely more wholesome than listening to old records. It’s more important that people know that some kind of pleasure can be derived from things that are around them—rather than to catalogue more stuff—you can do that forever; and if people aren’t going to have a reason to change, they’re never going to change.”

You write, “It’s curious that almost all the intellectual effort expended on the subject of sampling has been in its defense.” How does sampling fit into your view of retromania? And I wonder if you’ve read David Shields’ Reality Hunger, which argues for the value of literary sampling—freely lifting from other writers’ works, etc.—and what you thought of it.

I haven’t read Reality Hunger, but that seems like a sampled idea in itself, since Kathy Acker got there first, didn’t she?

Sampling’s a bit too vast a subject to get into. Obviously, I’m a big fan of it: some of my favorite genres, from hip hop to UK rave genres heavily influenced by hip hop (hardcore rave, jungle, trip hop, big beat), involve sampling. It can be done in all kinds of ways and produce different but equally compelling results. People can do the crate-digging obscurantist approach and make music that sounds like it’s been played by a band (or like a slightly aberrant, off-kilter version of live music), where you can never spot the samples or the joins, and that’s just great: some of my favorite people doing that are Luke Vibert a/k/a Wagon Christ, J Dilla, The Avalanches, the list is long. Equally, there are rave tunes and mainstream rap hits where a blatantly obvious and identifiable sample is used and it’s a masterpiece, like Kanye West’s “Thru the Wire,” which is little more than the original Chaka Khan song plus a beat and his rhymes. It’s hard to establish rules with sampling: West has also done songs that are equally dependent on the sample, such as the Daft Punk sampling “Stronger,” where the overall effect seems lame and lazy. And mash-ups are generally tedious, a dead end.

Sampling’s a bit too vast a subject to get into. Obviously, I’m a big fan of it: some of my favorite genres, from hip hop to UK rave genres heavily influenced by hip hop (hardcore rave, jungle, trip hop, big beat), involve sampling. It can be done in all kinds of ways and produce different but equally compelling results. People can do the crate-digging obscurantist approach and make music that sounds like it’s been played by a band (or like a slightly aberrant, off-kilter version of live music), where you can never spot the samples or the joins, and that’s just great: some of my favorite people doing that are Luke Vibert a/k/a Wagon Christ, J Dilla, The Avalanches, the list is long. Equally, there are rave tunes and mainstream rap hits where a blatantly obvious and identifiable sample is used and it’s a masterpiece, like Kanye West’s “Thru the Wire,” which is little more than the original Chaka Khan song plus a beat and his rhymes. It’s hard to establish rules with sampling: West has also done songs that are equally dependent on the sample, such as the Daft Punk sampling “Stronger,” where the overall effect seems lame and lazy. And mash-ups are generally tedious, a dead end.

I’ve argued in the past that sample-based music is more artistically interesting than a band where the music is all hand-played but the style is a pastiche. There is something jagged and disruptive and uncanny about sampling, at least when it’s done well, and this brings something new into the world, or creates a kind of modernist-like frisson. Whereas the pasticheur has painstakingly labored to learn how to sound unoriginal. I was interested to come across some art theory that took a similar stance, celebrating an architect who incorporated physical elements of an original building into a new structure, and arguing that this was more aesthetically exciting than postmodernist architects who merely referenced earlier styles and hodge-podged elements from different eras together.

You’re great on the idea that there are no more buried treasures out there. I used to feel like there were things I might never find—books, movies, records—which was frustrating but also nourishing in some way. That seems almost impossible now. Is there anything you’ve tried to find that you can’t?

There have definitely been things I’ve looked for online and been surprised that nobody has unleashed them into the commons. Some of the Silver series of electronic classical records that Philips put out in the 1960s through their Prospective 21eme Siecle imprint have not been digitized and shared as yet. There is this series of “Inventions for Radio” that mixed electronics and the voices of ordinary people talking about various concepts, put together by the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s Delia Derbyshire and Barry Bermange in the Sixties. A couple of them, including the famous and wondrously eerie installment titled “The Dreams,” can be found online, but others seem to have not been taped by fans at the time, and may well have been actually wiped by the BBC. They did that a lot during the Sixties with their radio and television output. What an outrageous concept that seems to us denizens of the archive-fever era! At any rate, you can’t find the other two of the four “Inventions” online, or seemingly anywhere.

So it is still possible to be frustrated, to find yourself unexpectedly returned to the scarcity economy.

Finally, in keeping with (part of) the spirit of this site, could you briefly recommend three or four of your favorite obscure music books that readers might not know?

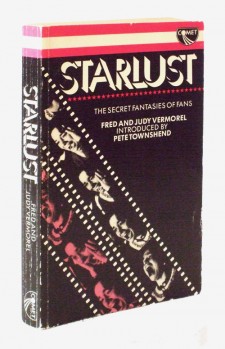

Starlust (1985) by Fred and Judy Vermorel has been out of print for years, but is just about to get reissued by my publisher as part of its Faber Finds imprint. Here’s how I blurbed it: “This fascinating and groundbreaking expose . . . lifts the lid on fan culture to reveal—and revel in—its literally idolatrous delirium. Yet, far from manipulated dupes of a cynical record industry, fans are shown to be subversive fantasists who use the objects of their worship as a means to access the bliss and glory they cannot find in their everyday lives and social surroundings. A lost classic of pop-culture critique that’s woven almost entirely out of the testimonials and confessions of the fans themselves, Starlust is above all a celebration of the power of human imagination.”

Starlust (1985) by Fred and Judy Vermorel has been out of print for years, but is just about to get reissued by my publisher as part of its Faber Finds imprint. Here’s how I blurbed it: “This fascinating and groundbreaking expose . . . lifts the lid on fan culture to reveal—and revel in—its literally idolatrous delirium. Yet, far from manipulated dupes of a cynical record industry, fans are shown to be subversive fantasists who use the objects of their worship as a means to access the bliss and glory they cannot find in their everyday lives and social surroundings. A lost classic of pop-culture critique that’s woven almost entirely out of the testimonials and confessions of the fans themselves, Starlust is above all a celebration of the power of human imagination.”

Big Noises (1991) is a really enjoyable book about guitarists by the novelist Geoff Nicholson. It consists of 36 short “appreciations” of axemen (and they’re all men; indeed, it’s quite a male book but quite unembarrassed about that). These range from obvious greats/grates like Clapton/Beck/Page/Knopfler to quirkier choices like Adrian Belew, Henry Kaiser, and Derek Bailey. Nicholson writes in a breezy, deceptively down-to-earth style that nonetheless packs in a goodly number of penetrating insights. I just dug this out of my storage unit in London a couple of months ago and have been really enjoying dipping into it.

The Boy Looked At Johnny (1978) by Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons is a curious thing: proof that a music book can be almost entirely wrong and yet remain a bona fide rockwrite classic. Allegedly written in a few days during an amphetamine bender, it’s subtitled “The Obituary of Rock and Roll,” but is really a requiem for the then-married authors’ broken-hearted belief in punk-as-revolution. Bitter and bitchy, strident and stylish, it had a huge impact on me at the time, as it did on loads of other impressionable youths; I was surprised to find out later that many people at the time of its release disapproved/deplored/dismissed it altogether. A big deal at the time, The Boy Looked At Johnny really has been forgotten. Few today even remember that perennially infamous newspaper opionator Burchill was once a music journalist—indeed, for a few years, the U.K.’s most famous rock writer.

Mentioned in this interview:

Retromania

2001: A Space Odyssey

Reality Hunger

Anthology Of American Folk Music

Songbook by Nick Hornby

Starlust

Big Noises

The Boy Looked at Johnny