Reviewed:

Reviewed:

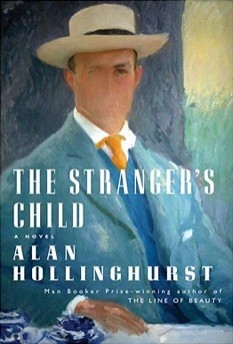

The Stranger’s Child by Alan Hollinghurst

Knopf, 448 pp., $27.95

English majors who revel in the not-so-secret sex lives of the Bloomsbury group will be more than prepared for Alan Hollinghurst’s new novel, The Stranger’s Child, which recounts the brief but lusty life of Cecil Valance, a poet who “would fuck anyone” before joining up in World War One and getting himself killed at the age of twenty-five in France. The obsession with the sexual preferences of famous writers could be viewed as the possible downfall of academia: who cares about the poems when you can bury yourself in letters, photos, and hearsay to reinterpret the work in light of scandalous biographical details?

The Stranger’s Child begins with Cecil’s visit to his boyfriend’s house, Two-Acres, and chronicles the ripple effect of his sexual escapades in the lives of the people who knew him and the people who go on to write his life into Literature with a capital L. Hollinghurst, the winner of the Booker Prize for The Line of Beauty and the author of several other novels, is a writer who understands the power of sensual sentences. As George, Cecil’s boyfriend, goes to introduce Cecil to his family, he feels “the chill of his own act of daring, bringing this man into his mother’s house . . . and felt his scalp, his shoulders, his whole spine prickle under the sweeping, secret promise.” And much later, after Cecil has died and been buried in the chapel at his family manse, Corley Court, George finds himself visiting the tomb, which includes a marble effigy of Cecil. In one of the novel’s most beautiful passages, George considers what a letdown it might have been if Cecil had lived: “He would have married, inherited, sired children incessantly. It would have been strange, in some middle-aged drawing-room, to have stood on the hearthrug with Sir Cecil, in blank disavowal of their mad sodomitical past. Was it even a past?”

Nearly every character in this novel asks the same question. As Cecil goes on being dead, even the people closest to him, including George, lose control over his legacy. The life and death of Rupert Brooke, to whom Hollinghurst makes several references in the text, is the obvious inspiration for Cecil. (Brooke may have preferred men, but that didn’t stop him from going skinny-dipping with none other than Virginia Woolf.) A wannabe academic in the novel remarks that “the War made his name, you’d have to agree; when Churchill quoted those lines from ‘Two Acres’ in The Times, Cecil had become a war poet.” (Churchill did, in fact, write about Brooke for the paper.) To tell the story of Cecil and his immediate legacy alone would be a tall order for any novelist, but Hollinghurst pushes it not one, not two, but three generations farther, creating an epic novel about the mined path of the literary biography.

The Stranger’s Child takes the other side — the gay side — of the literary romance, and has more in common with Brideshead Revisited than, say, A.S. Byatt’s Possession. Though Cecil is with George, he flirts with George’s sister Daphne, who goes on to marry Cecil’s brother, Dudley, who may be the only straight male character in the book. Her future husband and the father of her child are both homosexuals, and (fast-forward forty years) Paul Bryant, who works at the bank owned by her third husband, is a young gay man who’s interested in writing the life of — you guessed it — Cecil Valance. Paul has a fling with Peter Rowe, who works as a music teacher at Corley Court, Cecil’s family seat, which has now been converted into a school. Daphne, for one, wonders if Paul and Peter would be interested in Cecil if he had survived to old age. “To tell the truth I sometimes feel like I’m shackled to old Cecil. It’s partly his fault — for getting killed — if he’d lived we would have just been figures in each other’s pasts, and I don’t suppose anyone would have cared two hoots.”

Poor Daphne (along with the other female characters in this novel) gets the lesser amount of the novelist’s attention. Though Cecil says to George, “I don’t share your fastidious horror at the mere idea of a cunt,” this novel is really only concerned with the boys’ club founded by Lytton Strachey and Oscar Wilde that cares very little for the experience of the fairer sex.

When Paul does finally write his life of Cecil Valance, revealing to all that Cecil was most likely “queer” (it’s the Eighties!), it’s unfortunate that the reader doesn’t get to experience the fallout from Cecil’s family in real time — when we meet Paul again, it’s been twenty years, and Cecil’s great-grand-niece is telling us the strife his book caused, particularly to Daphne.

While it seems that Hollinghurst wants to press the reader toward the idea that a writer’s legacy is a crapshoot — a combination of being in the right place at the right time (or in this case, dying at the right place at the right time) and having enough kinky biographical material to make for a scandal — the novel itself is an argument against that philosophy. In fact, The Stranger’s Child does a thorough job of illuminating how readers and writers define themselves through very particular icons: those frozen in youth. When asked in an interview why so many people continue to be fascinated by her mother, Sylvia Plath’s daughter Frieda Hughes responded, “I think part of it is that people in a way analyze themselves through their subject. This is just my guess.” As The Stranger’s Child illustrates, that drive for self-analysis, through the unearthing and reinterpreting of the same material for generations to come, is what keeps literary biography in business. And isn’t it fun?

Jessica Ferri is a writer living in Brooklyn. You can visit her online here.

Mentioned in this review:

The Stranger’s Child

The Line of Beauty

Brideshead Revisited