Reviewed:

The Stranger Beside Me by Ann Rule

Pocket, 672 pp., $7.99

When I was an infant and a toddler in the mid 1970s, Ted Bundy was walking his notorious and grisly path, so that by the time I was a young boy his name was both a chilling specter and a macabre punch line, embodying everything that kids both fear and shrug off. I had forgotten how often his name was tossed around during my childhood, but was reminded while reading Ann Rule’s The Stranger Beside Me, an account of Bundy’s life and crimes as well as the story of a staggeringly unlikely coincidence.

After finishing Douglas Starr’s The Killer of Little Shepherds (reviewed elsewhere on the site this week), I was in the mood to linger in the true crime genre. Rule and Starr have different approaches and different strengths, but the subject of gruesome, incomprehensible behavior gives disparate books a strong sense of kinship. To write about a serial killer makes even a rigorous historian like Starr a little pulpy, and even a page-turning crowd-pleaser like Rule a little profound.

Rule is now a true-crime cottage industry, the author of more than 30 books, most of which have been bestsellers. She started her writing career with detective magazines, publishing pieces under a male pen name. The Stranger Beside Me was her first book, published in 1980, when she was in her mid-40s. She had signed the contract to write it while a series of murders in the Pacific Northwest were still unsolved. When Bundy became the prime suspect, it was a boon for Rule’s future book but also a punch to her stomach: She knew him.

In the early 1970s, Rule had been teamed with Bundy at a crisis hotline in Seattle, often working with him late at night, the two of them alone in a secured building. They would discuss his feelings for a woman who had rejected him; feelings that Rule found sensitive but normal. She would confide in him about the difficulties of single motherhood. Bundy was, she would later think, “a man with no adult criminal record at all, and certainly a man whose job record and educational background did not stamp him as a ‘criminal type.’”

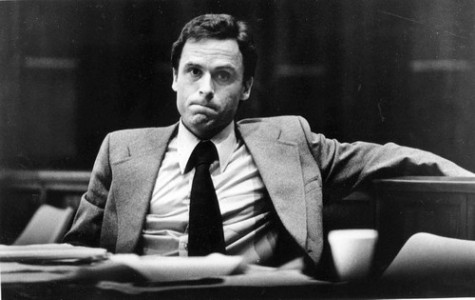

In The Killer of Little Shepherds, Starr writes about Cesare Lombroso, a 19th-century criminologist who stubbornly believed in “criminal types,” mostly identifiable, in his opinion, by facial symmetry (or lack thereof), skull indentations, and the measurement of the jaw. If only he had lived to see Ted Bundy. The name, in light of his deeds, is terrifying — the generic anonymity of Ted followed by the dull drumbeats of Bundy. But innocent of knowledge, it’s easy to imagine how people trusted him. To some, he was dashingly handsome. To anyone, he was thoroughly normal-looking. The country had been gripped with terror by the Manson murders in 1969. (I’m reading Helter Skelter now, and perhaps The Executioner’s Song

after that, but then I’ll stop; sanity demands a limit on this genre.) In 1970, when Jeffrey MacDonald allegedly killed his wife and children, people were ready to accept that the crime had been committed by a Manson Family-like group of drug-crazed hippies. (The MacDonald case is the subject of Joe McGinniss’ controversial 1983 bestseller, Fatal Vision

.)

Bundy hated hippies. He was a straight-laced Republican who had worked for Washington Governor Dan Evans. In a shaggy era, he kept his hair trim, his face clean-shaven, and his clothes tidy. In short, if Lombroso saw Bundy’s mug shot, he’d likely offer him a lifetime acquittal.

But Lombroso’s theory of how to identify criminals with the naked eye was being challenged by a new generation of scientists who believed in treating crime scenes as a lab. Starr refers to Edmond Locard, a forensic scientist who started as an assistant to Dr. Alexandre Lacassagne, one of the two leading men in Little Shepherds (the other is serial killer Joseph Vacher). Rule quotes Locard early on in her book about Bundy: “Every criminal leaves something of himself at the scene of a crime — something, no matter how minute — and always takes something of the scene away with him.”

Given this fact, it borders on unbelievable how lucky authorities sometimes have to be, even when chasing someone who left behind a trail as long and bloody as Bundy did. We know he killed dozens of women — Rule conjectures, along with some police, that the real number could have been 100 or more — but the only conclusive piece of physical evidence in his trial was a set of bite marks left on one victim.

The evidence of his relationship with Rule, in the form of personal letters from jail, among other things, is a rare look at the performative face of a killer. In May 1976, he wrote to her while imprisoned in Utah:

. . . after conducting numerous tests and extensive examinations, [they] have found me normal and are deeply perplexed. Both of us know that none of us is “normal.” Perhaps what I should say is that they find no explanation to substantiate the verdict or other allegations. No seizures, no psychosis, no disassociative reaction, no unusual habits, opinions, emotions or fears. . . . I may have convinced one or two of them that I am innocent.

When they first met, Rule experienced something like a maternal feeling for Bundy, and she carried a vestige of that feeling for a remarkably long time, after many people would have recoiled from him. Then again, there was an inexplicable urge on the part of many women to stand by him. Most of them were strangers to him. Young female supporters attended his trial, and Rule received letters from many women who were sure he was simply misunderstood.

As anyone in her position might, Rule tried to get to the roots of Bundy’s murderousness, but her psychoanalysis is finally insufficient. Bundy was an illegitimate child, who believed for much of his youth that his mother was his older sister, and that his grandparents were his mother and father. That wasn’t entirely uncommon in the 1940s and ‘50s. And there’s reason to believe that he was raised in a violent household, but sadly, that also is not rare.

Rule’s presentation of these formative facts don’t add up to an explanation of how or why someone with Bundy’s considerable intelligence and charm led such a terrifying double life. It wasn’t until presented with photographic evidence of Bundy’s crimes that Rule finally closed her mind to the remote possibility of his innocence, to the possibility of sympathizing with him, to the possibility that the person she thought she knew was somehow as real as the person Bundy really was.

Mentioned in this review:

The Stranger Beside Me

The Killer of Little Shepherds

Helter Skelter

The Executioner’s Song

Fatal Vision