Reviewed:

Spanning the Century: The Life of W. Averell Harriman, 1891-1986 by Rudy Abramson

779 pp., 1992, Currently out of print

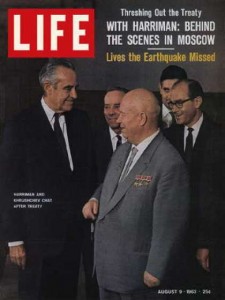

As the U.S. Senate considers the New START Treaty and The New Republic notes potential loopholes in other international nuclear agreements, it may be a good moment to reconsider the life of William Averell Harriman, widely known as W. Averell or Averell, Ave to his friends, Honest Ave the Hairsplitter to detractors, a man who, among a zillion other things, fought hard for nuclear arms reduction, particularly as President Kennedy’s representative at the negotiations for the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. Rudy Abramson relays the scene in his long out-of-print masterpiece Spanning the Century: The Life of W. Averell Harriman, 1891-1986: “‘Since we have agreed to a have a test ban, let us sign it now and fill in the details later,’ Khrushchev bubbled as they sat down to their first meeting. Harriman pushed a legal pad across the table in the Premier’s direction. ‘Fine,’ he replied, ‘you sign first.’”

Harriman is perhaps best known for his diplomatic roles during World War II, when he served as President Roosevelt’s special envoy to the United Kingdom and later as ambassador to the Soviet Union, but he found time to do a few other things as well. He was an investment banker (the Harriman in Brown Brothers Harriman), chairman of various railroads (including Union Pacific from 1932-1946), and Midas-like investor. A man from unparalleled privilege who exemplified the nearly forgotten term noblesse oblige, he was an unabashed liberal and a New Deal administrator (in 1956, Murray Kempton noted that he still “held aloft the lamp of the New Deal”). Under President Truman, he was Secretary of Commerce, U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom, and administrator of the Marshall Plan. Later, he was governor of New York, Assistant Secretary of State for East Asia under Kennedy, and President Lyndon Johnson’s representative at the fraught peace talks with North Vietnam, to which he devoted bewildering energy. Somehow he also found time for fun projects, such as building the Sun Valley ski resort, owning race horses, and playing polo. Not even Benjamin Franklin could wring more hours out of a day. He had a full personal life, with three marriages and several children. He largely helped raise the high society band leader and pianist Peter Duchin (the son of deceased friends). His third wife was Pamela Harriman (first married to Winston Churchill’s son Randolph), a Democratic king-maker who helped put Bill Clinton in the White House. (She died while serving as U.S. ambassador to France in 1997.)

Spanning the Century is a monumental book about a complex and important man. Abramson’s faultless prose opens up great vistas at the intersections of American business, political, and diplomatic history. When the book appeared in 1992, Library Journal offered this tepid appraisal:

Here is the first full biography of a man whose diplomatic contacts spanned Stalin and Le Duc Tho, who served presidents from Franklin Roosevelt to Lyndon Johnson and sought the office himself, and who was governor of New York and inherited a great family fortune. . . .Unfortunately, the story often proceeds in a manner too plodding for most general readers, who remain adequately served by Harriman’s memoir, Special Envoy to Churchill and Stalin, and by Walter Isaacson and Evan Thomas’ biography, The Wise Men. Still, given Harriman’s importance, many academic libraries will need this book.

He served President Carter as well, but no matter. This review does not lead you to believe that you, as a general reader, could or might want to learn an awful lot about Harriman’s role in Iran in 1951, or the ins and outs of the early-20th-century railroad business, or about how Sun Valley was set up and marketed (quite a tale), or about Harriman’s sister’s pet project, a pro-New Deal magazine called Today that acquired (via Harriman) News Week to form the Newsweek that we knew until recently. That review doesn’t lead you to believe that you can receive, via Abramson, an education in the complexities of the 1920s Soviet Manganese Concession. (Conceded to Harriman, of course.) This general reader spent more time thinking about manganese than a general reader probably should. (Abramson relays this: after four hours at a table reviewing a document with Trotsky and an interpreter, Harriman tried to make polite conversation, and told Trotsky that while the 20th century will be known as the American century, perhaps the 21st will be known as the Russian one. Trotsky shot back that he was only willing to concede the first half of the 20th. Trotsky also noted — to Maxim Litvinov, not to Harriman – that rumors were spreading that he was on the Harriman payroll!)

Harriman was intriguing, in part, because, despite his abnormally high energy and intelligence, he was always just a little late in becoming what he wanted to be. (James Chace, reviewing Abramson’s work in The New York Times Book Review in 1992, called Harriman a “Horatio Alger with deep pockets.”) Initially discouraged from rowing crew at Yale, he became a fanatical crew expert, traveling to England to study techniques. He realized somewhat late in the game that he wanted to be a great polo player, and in his thirties he doggedly pursued that dream, becoming a respected player (he helped the U.S. team defeat Argentina in the 1928 world championship). He was a little late to the New Deal, but took low-rung jobs, which paid off when he became a major player during World War II. He always wanted to be president but, late to the game of elected office, became governor of New York (not bad for a first elected position). He went no further, and in one of the ironies of class in America, saw his hopes of being president dashed by Tammany Hall boss Carmine De Sapio. (Harriman ran a respectable campaign for the Democratic nomination in 1956, but Adlai Stevenson won it.)

Harriman was intriguing, in part, because, despite his abnormally high energy and intelligence, he was always just a little late in becoming what he wanted to be. (James Chace, reviewing Abramson’s work in The New York Times Book Review in 1992, called Harriman a “Horatio Alger with deep pockets.”) Initially discouraged from rowing crew at Yale, he became a fanatical crew expert, traveling to England to study techniques. He realized somewhat late in the game that he wanted to be a great polo player, and in his thirties he doggedly pursued that dream, becoming a respected player (he helped the U.S. team defeat Argentina in the 1928 world championship). He was a little late to the New Deal, but took low-rung jobs, which paid off when he became a major player during World War II. He always wanted to be president but, late to the game of elected office, became governor of New York (not bad for a first elected position). He went no further, and in one of the ironies of class in America, saw his hopes of being president dashed by Tammany Hall boss Carmine De Sapio. (Harriman ran a respectable campaign for the Democratic nomination in 1956, but Adlai Stevenson won it.)

Harriman seems like he was on the lookout for his own blind spots, and it appears he found epic ways to correct them. At one point in the late 1910s, he became known as “the Steamship King,” partially through a takeover of American Ship and Commerce, which he then parlayed into an alliance with Hamburg-American. Abramson writes:

Although Harriman was not publicly attacked for it, the fact that he had not served in uniform during the war [World War I] was not forgotten. Some of his old Yale friends thought his behavior shameful — first avoiding service in uniform, then rushing into a lucrative business collaboration with the Germans. His former roommates, Charley Marshall and George Dixon, stopped speaking to him for years. Most members of Yale ‘13 had fought in the war, and eight of them had been killed.

It almost seems as if this scorn resulted in 50 years of stellar service to the United States. Years later, Harriman was accused of being soft on Nazis, having been involved in mine deals with the Third Reich (deals that ended in 1935). He defended himself against these charges while governor, and his record in helping Britain during its darkest hour, as Lend-Lease administrator, speaks for itself. It may be worth noting here yet another difference between Roosevelt, a man for whom thinking anew and acting anew was possible, and subsequent presidents. Harriman’s title was to be Defense Expediter. Abramson writes, “The press, suspecting that Roosevelt was once again establishing a wartime operation outside the established bureaucracy, wondered whether Harriman would report directly to the President or through the conventional channel, Ambassador Winant. ‘I don’t know,’ Roosevelt replied, ‘and I don’t give a damn, you know.’”

Harriman’s life contains a valuable lesson in intergenerational dynamics. Abramson tells the story of how his subject was nearly frozen out of the Kennedy administration in 1961 (and thus nearly frozen out of seven successful years as a diplomat), and would have been if not for the efforts of his former assistant, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. Not that Harriman hadn’t tried to be helpful to Kennedy. Abramson writes:

Using Averell’s reports, Kennedy skillfully denounced the Eisenhower administration’s ignorance and neglect of African policy, a nimble way to appeal to American blacks without alienating southern whites. Harriman encouraged the Kennedy campaign to be more direct, and ‘comment on the damage to our position in Africa by the reports of discrimination and injustice that still exist in our country.’ But that was advice the Kennedy campaign chose not to heed.

They were also happy to have Harriman’s monetary contributions. But when the time came to fill jobs, it looked as if he would be left out.

More than a decade earlier, Schlesinger had been Harriman’s special assistant in Paris, when Harriman was administrator of the Marshall Plan. John and Robert Kennedy regarded Harriman as a relic from the Roosevelt-Truman past, who, for all his diplomatic credentials, was tainted by association with Kennedy family enemy De Sapio. But Schlesinger, close Kennedy friend and adviser, lobbied for his former boss’ inclusion. In his memoir A Life in the 20th Century: Innocent Beginnings 1917-1950, Schlesinger writes of Harriman:

What struck me was that, despite the formidable gap in age, experience, status, knowledge, and savoir-faire, not to mention wealth, he wasted no time on ceremony, treated me as a contemporary, instructed me to call him by his first name and placed our relations on the basis of ease and candor.

Yet Schlesinger also admits that “[W]orking for Harriman was not always easy. He was a no-frills chief, single-minded in his concentration on the job. One evening he took me to a dinner given by a fashionable French hostess. Busy at the office, we arrived late, and after dinner, Averell rose to return to our labors.” He could be a tough boss, but Schlesinger notes he inspired “extraordinary devotion.” Schlesinger knew that Kennedy did not know Harriman like he knew him, and so he (along with John Kenneth Galbraith), got Harriman’s foot in the door. It was not long before Kennedy recognized what Harriman brought to the table — knowledge, connections, and know-how — and utilized him accordingly. By 1968, Abramson writes, “Harriman had no closer friend in political life” than the recently assassinated Robert Kennedy.

Spanning the Century is full of smart little details from odd corners of history. When China and India went to war in 1962, Kennedy dispatched Harriman to New Delhi. Abramson writes:

On such occasions, the long haul across the ocean was made in windowless, uninsulated aerial tankers, outfitted with portable passenger seats with bunks above them in the upper half of the fuselage. The ‘McNamara Specials,’ as the flying torture chambers were called, subjected passengers to brain deadening jet noise and temperatures rising and falling by sixty degrees. To traveling companions, Harriman seemed strangely immune to the gross discomfort.

I knew this was the approximate sort of plane, with attendant discomfort, that Churchill used to cross the Atlantic many times during World War II, but I was stunned to read that a statesman — with unlimited personal wealth and prestige — would fly this way in 1962, the golden age of luxurious air travel.

Abramson, who died at 70 in 2008, spent many years at the Los Angeles Times, working as science correspondent and later as Pentagon and White House correspondent, before devoting his efforts to the preservation of American heritage sites, such as Civil War battlefields. As a biographer, Spanning the Century proves he was the peer of such masters of the art as Ron Chernow, Robert Caro, and David McCullough.

Reviewing Spanning the Century in The New Republic in 1992, Jacob Heilbrunn noted its “Michenerian length” — a length that has come to be expected, I think, in political biographies that cover intricate events and include some color and extra context. Would any reviewer today bother to note the “Michenerian length” of a biography by Chernow? While Caro and McCullough might have been out in front on this trend, it is interesting to compare Abramson’s biography of Harriman with longtime New Yorker writer E.J. Kahn, Jr.’s 1981 biography of Harriman’s younger contemporary (and early co-investor in what became PanAm) John Hay “Jock” Whitney (1904-1982). Kahn’s Jock: The Life and Times of John Hay Whitney, deals with a man just as wealthy, just as energetic, with as much eventful, diverse life experience in war, business, and politics; and while not as important as Harriman, important nonetheless. Kahn’s great book about a great man clocks in at 326 pages, pre-index, to Abramson’s 733, pre-index and notes. Roy Jenkins’ Truman (1986) was substantially shorter, by nearly two-thirds, than his subsequent efforts in Gladstone (1997) and Churchill (2002). Spanning the Century, it seems, was part of a vanguard that helped pave the way for the 18-wheeler biographies that have come to be expected today. Chace noted in his review, “I found myself asking myself why I liked this remote, humorless, hard-driving figure.” It’s not a bad question. George Kenan provided Chace with one possible answer, via a Russian observer of Harriman: “there goes a man!”

Paul Devlin is a Ph.D. student in English at SUNY Stony Brook. His work has appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle, the Daily Beast, Slate, The Root, and the New York Times Book Review.