Reviewed:

The Only Game in Town: Sportswriting from The New Yorker edited by David Remnick

Random House, 512 pp., $30.00

Rules of the Game: The Best Sportswriting from Harper’s Magazine edited by Matthew Stevenson and Michael Martin

Franklin Square Press, 368 pp., $14.95

I have certainly spent more hours over the course of my life watching NCAA basketball games—or NFL games or Major League Baseball games—than I have reading Shakespeare, which is a shame because, like everyone, I have a limited number of leisure hours, and because I like Shakespeare so much more than I like Mike Krzyzewski or Roy Williams or any of the players they have coached; more than I like the Baltimore Ravens or the Kansas City Chiefs; more than I like Jorge Posada or Alex Rodriguez; and so much more than I like Greg Gumbel, Howie Long, Clark Kellogg, Terry Bradshaw, and all the other men in shiny suits who banter about the “X factors” in various games. This is what I tell myself, at least. When faced with the choice of reading Flaubert or watching Game Six of the NBA finals, I choose Kobe every time. Which would be fine if I didn’t then flog myself for ceding so many neurons to halftime shows and Bud ads, if I weren’t such a peculiarly tormented and conflicted follower of games—tugged by sports, by their controlled violence, their unscripted surprises, the pastoral beauty of a green field on my flat screen, but wary of my brain being swallowed by the likes of John Madden. (He may have retired, but his shadow is large, his echo loud.)

There is only one sports-related experience that silences my inner guilt: reading sportswriting in The New Yorker. The magazine’s coverage not only simultaneously delivers the joys of sports and of good writing, thus momentarily aligning my warring passions, but also, with its less macho, more civilized approach to sports makes me feel like I can be—indeed, am—a fan. For the ambivalent and reasonably literate sports fan, sportswriting in The New Yorker offers a special refuge from the noisy, occasionally brutish sports media. If this hasn’t been apparent issue to issue—under David Remnick, the magazine publishes about 10 sports stories a year, and I receive each issue containing one as a special act of grace—it should be clear now, with the publication of The Only Game in Town, the first anthology of the vaunted magazine’s sportswriting.

It’s a wide-ranging book. You get comparative sociology, in a profile of the Chinese NBA star Yao Ming by Peter Hessler, who observes that, in America, “where community leagues and school coaches are plentiful,” great basketball players “emerge from an enormous pyramid of participants,” whereas, in China, future national team members are plucked early, based only on their height, to attend schools such as Shanghai’s Xuhui District Sports School, where Ming began training in third grade (when he was 5’7”). “We go to the schools and look at the children’s height, and then we check their parents’ height,” a Xuhui coach tells Hessler.

It’s a wide-ranging book. You get comparative sociology, in a profile of the Chinese NBA star Yao Ming by Peter Hessler, who observes that, in America, “where community leagues and school coaches are plentiful,” great basketball players “emerge from an enormous pyramid of participants,” whereas, in China, future national team members are plucked early, based only on their height, to attend schools such as Shanghai’s Xuhui District Sports School, where Ming began training in third grade (when he was 5’7”). “We go to the schools and look at the children’s height, and then we check their parents’ height,” a Xuhui coach tells Hessler.

You get social psychology and marketing theory. Henry Louis Gates, Jr., reads deeply in both fields—he cites the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology—to argue that Michael Jordan became “the greatest corporate pitchman of all time” because his initial endorsements were so strategic. He chose companies whose brand images—Coke, “enduring . . . and authentic;” McDonald’s, “reliable, fast, wholesome, and family-minded”—would help brand him in turn.

And you get loads of humor. In Rebecca Mead’s 2002 profile of Shaquille O’Neal (“A Man-Child in Lotusland”), Shaq talks with Mead about, of all things, his death: “I started to think about what my mausoleum would look like, and I thought it should be all marble, with Superman logos everywhere,” he tells Mead. “There would be stadium seating, and only my family would have the key, and they would be able to go in there and sit down, like in a little apartment. My grave would be right there, and there would be a TV showing, like, an hour-long video of who I was.” When Shaq “speaks on a cell phone,” Mead observes, “he holds it in front of his mouth and talks into it as if it were a walkie-talkie, and then swivels it up to his ear to listen, as if the phone were a tiny planet making a quarter orbit around the sun of his enormous head.” And those are just the entries about pro basketball.

The New Yorker provides a funhouse view of sports. Fringe pursuits such as parkour, bullfighting, and extreme skiing take up far more space in the magazine than they do in the rest of Sports Nation. Superstars in major professional sports only occasionally pass, swing, and dribble across The New Yorker’s pages, and at odd times. Readers waited until June 2010, the year after he’d broken the all-time record for Grand Slam championships, to get a sustained look at Roger Federer (“Anxiety on the Grass” by Calvin Tompkins), which focused less on Federer’s spectacular career than on a recent slump. Gates’ profile of Jordan arrived in 1998, after the world’s most famous athlete had already retired once. More often, the superstars never show up at all, bypassed for more obscure choices. In the run-up to the 2004 Olympics, backstroker Natalie Coughlin was profiled; Michael Phelps was not. The magazine has profiled the American tennis doubles team of Bob and Mike Bryan, but not Pete Sampras; Ivan Lendl’s golfing daughters, but not Annika Sorenstam; and, in LeBron James’ second NBA season, the University of Connecticut’s Diana Taurasi, but not LeBron James. You can also flip through a hundred issues without finding any mention of who won the Super Bowl. Calling yourself a sports fan if your only source of sports coverage were The New Yorker would be a bit like calling yourself a human being if you were raised by wolves. The magazine operates in its approach to covering sports like the athletic department of an Ivy League college, with a genteel aloofness.

Yet a question persists: Why would I read writing about sports anywhere else? And it only grows louder if you read The Only Game in Town, as I did, alongside recent anthologies gathered largely or entirely from sports publications and newspaper sports pages, including Fifty Years of Great Writing

Yet a question persists: Why would I read writing about sports anywhere else? And it only grows louder if you read The Only Game in Town, as I did, alongside recent anthologies gathered largely or entirely from sports publications and newspaper sports pages, including Fifty Years of Great Writing, a collection of pieces from the first five decades of Sports Illustrated, and a few of the annual volumes of the Best American Sports Writing series. It turns out that my mild aversion to jockmedia—the jockcomedians on SportsCenter and that network’s beat jockreporters and legions of jockbloggers—extends to jockwriters, who exist in abundance.

Jockwriters spray action neologisms—Thump-thump! (the sound of a jab thrown by a hockey player); zzzzt (the sound of a soccer ball struck by Mia Hamm)—punctuate baroquely (!!!!!!!, ………); spew pop-cultural references (the Geico Caveman, Tila Tequila); and liberally curse and generally address you, dear reader, as a fraternity brother who has asked about the game. These are among the first sentences of Patrick Hruby’s ESPN.com story about hockey fight fans, “Men Who Love Goons”: “Seriously, that’s Jon ‘Nasty’ Mirasty down there, circling the ice like a suicide gunboat. And what about Trevor Gillies? Dude has a longer fight card than Evander Holyfield. Why don’t they just go?” I’ll grant that Hruby is channeling a fan’s voice in that passage, but his own is not much different. The jockwriter’s voice is loud, as though he were projecting across a bank of lockers. The jockwriter is always flexing.

In 60 years, if jockwriting is still read, it will be for the same reason we still read the mid-century sportswriter W.C. Heinz, whose work is included in the 1999 super-anthology The Best American Sports Writing of the Century edited by David Halberstam: as a window onto the consciousness of sports fans in a particular time. You don’t so much read Heinz’s 1951 profile of the Brooklyn boxer Al “Bummy” Davis as watch it float like smoke from the mouth of a portly man in suspenders holding court at a newspaperman’s bar. It begins: “It’s a funny thing about people. People will hate a guy all his life for what he is, but the minute he dies for it they make him out a hero and they go around saying that maybe he wasn’t such a bad guy after all because he sure was willing to go the distance for whatever he believed or whatever he was.”

The sportswriting of nostalgia, a contemporary strand of the craft found in abundance in Fifty Years of Great Writing—in remembrances of Johnny Unitas and Secretariat, and in profiles of John Wooden and Bill Russell—relies heavily on sentimentality. There is, in much of this work—especially in Frank Deford’s pieces on Russell and Unitas—a politely expressed but nonetheless irritating insider tone that coexists with an aw-shucks tone. Deford writes of Russell: “When I try to explain the passion of Russell himself and his devotion to his team and to victory, I’m inarticulate. It’s like trying to describe a color to a blind person. All I can say, in tongue-tied exasperation, is, You had to be there. And I’m sorry for you if you weren’t.” Deford begins his remembrance of Unitas like this: “Sometimes, even if it was only yesterday, or even if it just feels like it was only yesterday . . . Sometimes, no matter how detailed the historical accounts, no matter how many the eyewitnesses, no matter how complete the statistics, no matter how vivid the film . . . Sometimes, I’m sorry, but . . . Sometimes you just had to be there.” The reader cannot say he wasn’t warned.

It may not be possible to explain why sportswriting in The New Yorker is so much better than most of what’s out there without resorting to tautology: The New Yorker’s sportswriting is so good because it’s published in The New Yorker. But I can identify some general qualities that make it consistently great and, in more cases than not, deserving of an audience long after its subjects retire or perish.

It is, to begin, proudly intelligent. This trait is perhaps most visible in its figurative language: Specter writes of how “Suffering is to cyclists what poll data are to politicians; they rely on it to tell them how well they are doing their job”; Mead describes how, for O’Neal’s 30th birthday party, the tennis court behind his house “was decorated with long tubular balloons in red and yellow and blue, twisted together like something from a medical diagram of the lymphatic system.” It takes a refreshing, almost anthropological distance on its subjects. Mead’s profile of O’Neal can be taken as a sort of inspired ethnography of one outsized man, his “size-22 basketball shoes . . . all white and finished with a shiny gloss, reminiscent, in their sheen and size, of the hull of a luxury yacht” and his skin “tide-marked with drying sweat.” And it’s accessible to readers who have low sports literacy. The highlights—of superstars’ careers and teams’ successes—are diligently but efficiently introduced.

It’s also possible the writing is so good because it’s not done by sportswriters, who don’t exist there as a pure species. The magazine employs specialist writers in classical music (Alex Ross), visual art (Peter Schjeldahl), medicine (Atul Gawande), and other fields, but its staff doesn’t include a single full-time sportswriter. (Roger Angell, the magazine’s sui generis writer on baseball, to whom The Only Game in Town is dedicated, is a possible exception, but at 90, he now only writes about one story a year.) New Yorker writers cover sports as a respite between other subjects—culture, politics, religion, technology. Ben McGrath, who writes about sports more frequently than any other staffer, filed stories about a murder in New Jersey, the Tea Party movement in Kentucky, and Mayor Bloomberg (and Talk of the Town stories about license plates, a maritime historian, and Yale recruiting, among many other topics) between his 2008 profile of Lenny Dykstra and a piece about baseball’s spring training earlier this year. Is the variety of his writing experiences part of the reason he was able to capture with such verve in his July profile of David Ortiz the cat-and-mouse ritual that played out in the Red Sox’s locker room between the aging slugger and a female reporter, whose questions he avoided by flexing his biceps, “exposing the tattoo of his late mother’s face below his right shoulder,” and later, after motioning to a clubhouse TV that displayed a shot of lettuce in a news report about E. coli and shouting, “Is that weed?,” escaping? Is it forced literary cross-training that keeps New Yorker writers flexible and fresh? (And would the quality of Sports Illustrated and ESPN’s writing be much improved if their writers were allowed to rotate to other magazines for a couple of months each year? Even professional athletes get a break from sports.)

The magazine’s sports coverage also benefits from agile, unyielding, even athletic reporting, which has been a genetic feature of The New Yorker since the magazine’s birth. In his profile of Bill Bradley, when the future senator was a college basketball star, John McPhee not only watched his subject in the Princeton gym at tournament games, but also visited Crystal City, Missouri, Bradley’s hometown, and the gym where Bradley used to practice with “ten pounds of lead slivers in his sneakers” and, to develop the ability to dribble without looking at the ball, “wore eyeglass frames that had a piece of cardboard taped to them so that he could not see the floor.” He met Bradley’s father, a bank president who started working at his bank in 1921 as a penny shiner, and, because he suffers from a form of spinal arthritis that prevents his bending over, “uses a long wooden tweezers to pick up objects from the floor.” He learned that Bradley’s maternal grandfather was a coffee salesman who was once bit by a stallion, and noticed that in Crystal City, “weeds sometimes grow at 45-degree angles out of the clefts where the streets meet the curbstones.”

The magazine’s sports coverage also benefits from agile, unyielding, even athletic reporting, which has been a genetic feature of The New Yorker since the magazine’s birth. In his profile of Bill Bradley, when the future senator was a college basketball star, John McPhee not only watched his subject in the Princeton gym at tournament games, but also visited Crystal City, Missouri, Bradley’s hometown, and the gym where Bradley used to practice with “ten pounds of lead slivers in his sneakers” and, to develop the ability to dribble without looking at the ball, “wore eyeglass frames that had a piece of cardboard taped to them so that he could not see the floor.” He met Bradley’s father, a bank president who started working at his bank in 1921 as a penny shiner, and, because he suffers from a form of spinal arthritis that prevents his bending over, “uses a long wooden tweezers to pick up objects from the floor.” He learned that Bradley’s maternal grandfather was a coffee salesman who was once bit by a stallion, and noticed that in Crystal City, “weeds sometimes grow at 45-degree angles out of the clefts where the streets meet the curbstones.”

McPhee is a writer who must follow each ray of his curiosity to its end in facts, including whether Bradley, as sources tell him, actually possesses superior peripheral vision, which he satisfies by accompanying Bradley to the office of a Princeton ophthalmologist (who verifies it). Whenever a New Yorker writer is detoured from the court or the field by a chase after knowledge, however quixotic, the writer is pulling a page from McPhee. McGrath does it when he speaks with Robert K. Adair, a professor emeritus at Yale and the author of The Physics of Baseball, to inquire about the science behind the knuckleball. (“Baseball isn’t rocket science,” Adair told him. “It’s a lot harder.”) And Hessler does it when he searches Houston’s Chinatown for fans of Yao Ming and pays a visit to the star’s barber.

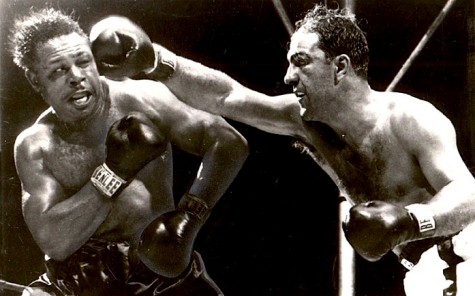

Some credit is due to A. J. Liebling any time a New Yorker writer injects humor into a dispatch from the world of sports. Liebling was an orotund, Ruthian figure whose other principal subject was food, which he wrote about in memoir form, describing both the food itself and his Olympic appreciation of it (a “dozen, or possibly eighteen, oysters, and a thick chunk of steak topped with beef marrow” was, to him, a “sensibly light meal”), and he brought something of a glutton’s brio to his pieces on boxing, smuggling literary and artistic references into the ring. As its title, “Ahab and Nemesis,” suggests, Liebling frames his 1955 account of a fight between Archie Moore and Rocky Marciano as a futile whale hunt, with Moore as the hunter who was “honing his harpoon for the White Whale.” When Marciano gets up after being knocked down, Moore “may have felt, for the moment, like Don Giovanni when the Commendatore’s statue grabbed at him—startled because he thought he had killed the guy already—or like Ahab when he saw the Whale take down Fedallah, harpoons and all.” Moments earlier, when the two fighters shook hands before the first round, Liebling “could see Mr. Moore’s eyebrows rising like storm clouds over the Sea of Azov.” Liebling, of course, follows the Ahab metaphor with humorous intentions—we’re meant to delight in his Mellvillian reading of a Rocky Marciano fight—but it’s both apt and persuasive: we begin to appreciate the bout as the epic it was.

Some credit is due to A. J. Liebling any time a New Yorker writer injects humor into a dispatch from the world of sports. Liebling was an orotund, Ruthian figure whose other principal subject was food, which he wrote about in memoir form, describing both the food itself and his Olympic appreciation of it (a “dozen, or possibly eighteen, oysters, and a thick chunk of steak topped with beef marrow” was, to him, a “sensibly light meal”), and he brought something of a glutton’s brio to his pieces on boxing, smuggling literary and artistic references into the ring. As its title, “Ahab and Nemesis,” suggests, Liebling frames his 1955 account of a fight between Archie Moore and Rocky Marciano as a futile whale hunt, with Moore as the hunter who was “honing his harpoon for the White Whale.” When Marciano gets up after being knocked down, Moore “may have felt, for the moment, like Don Giovanni when the Commendatore’s statue grabbed at him—startled because he thought he had killed the guy already—or like Ahab when he saw the Whale take down Fedallah, harpoons and all.” Moments earlier, when the two fighters shook hands before the first round, Liebling “could see Mr. Moore’s eyebrows rising like storm clouds over the Sea of Azov.” Liebling, of course, follows the Ahab metaphor with humorous intentions—we’re meant to delight in his Mellvillian reading of a Rocky Marciano fight—but it’s both apt and persuasive: we begin to appreciate the bout as the epic it was.

Bill Barich’s “Race Track,” a bildungsroman of betting garnished by an Altmanesque cast of horse people, also makes an epic of the everyday. Barich’s piece anticipates the sports stories of David Foster Wallace, with their deft blend of personal narrative and reportage (insofar as it’s possible to anticipate such singular things), and is the most memorable of several strong pieces of personal writing in the anthology. Nancy Franklin (“Back to the Basement”) writes about the long-held illusion that she was a “killer” ping pong player and the final realization that she was not; William Finnegan (“Playing Doc’s Games”) surfs the cold, rough waters of San Francisco; Haruki Murakami (“The Running Novelist”) considers the mysteries of running; John Cheever writes of overcoming his animus for baseball (“National Pastime”); and Adam Gopnik movingly remembers his mentor in football and postmodern art (“The Last of the Metrozoids”). With their cerebral and occasionally reluctant approach to sports, these writers are The New Yorker’s answer to the jockwriter: the nerd-jock.

None is more cerebral than Barich, who studies the Daily Racing Form and apprentices himself to handicapping gurus such as Andrew Beyer, whose book Picking Winners described a “perfected” system based on “digital computer research” (“Race Track” was published in 1980), and stumbles as he attunes himself to his intuition. Before one race, he vacillates between Little Shasta, whose name reminds him of a camping trip he’d taken with his brother on Shasta Lake, and Top Delegate, the horse to choose based on a “sensible reading of the Form.” Barich decides finally on Shasta, but then “face-to-face with a ruddy-skinned ticket seller in a black cardigan sweater,” changes his mind. Little Shasta goes wire to wire.

Barich’s interest in horse racing was sparked by visits to a Long Island OTB while he was caring for his ill mother, and he embarks on his weekslong idyll—or bender—at Golden Gate Fields soon after her death. Barich’s piece has the shaggy narrative and cast of characters that you might expect to find in Harper’s, which also released an anthology of sportswriting, Rules of the Game, this summer. I don’t know what act of the editorial gods brought these books into head-to-head competition, but only the fiercest partisans of Harper’s will want to claim that its anthology is better. That said, I am a fierce partisan of Harper’s. I grew up in Kansas, and as a teenager always appreciated that I could understand almost everything in the magazine, unlike The New Yorker, without ever having lived in New York, and I will claim that the Harper’s collection is just as good as The Only Game in Town.

In fact, the two books are ideal companions. The Harper’s anthology satisfies the literary reader’s appetite for stories about failure, which is common enough in sports but relatively unchronicled. For “Down and Out at Wrigley Field,” Rich Cohen embedded himself with the Chicago Cubs during a stretch in August 2001 that included a seven-game losing streak. Cohen describes a couple of moments from games, but fixes his eyes mostly on the periphery of the field: the battles Sammy Sosa wages with his teammates to play salsa in the locker room, which he wins by simply plugging in his radio and turning it up louder than the Pearl Jam; the body of Joe Girardi, then the Cubs catcher, which Cohen, having seen naked, describes as “old-fashioned, a body from the Great Depression: thick torso and heavy arms, social realism, a WPA poster;” and journeyman third baseman Jeff Huson’s teeth, “as small and perfect as white Chiclets.”

In fact, the two books are ideal companions. The Harper’s anthology satisfies the literary reader’s appetite for stories about failure, which is common enough in sports but relatively unchronicled. For “Down and Out at Wrigley Field,” Rich Cohen embedded himself with the Chicago Cubs during a stretch in August 2001 that included a seven-game losing streak. Cohen describes a couple of moments from games, but fixes his eyes mostly on the periphery of the field: the battles Sammy Sosa wages with his teammates to play salsa in the locker room, which he wins by simply plugging in his radio and turning it up louder than the Pearl Jam; the body of Joe Girardi, then the Cubs catcher, which Cohen, having seen naked, describes as “old-fashioned, a body from the Great Depression: thick torso and heavy arms, social realism, a WPA poster;” and journeyman third baseman Jeff Huson’s teeth, “as small and perfect as white Chiclets.”

George Plimpton, in a virtuosic dispatch from the 1980 Moscow games (which the U.S. boycotted) shares a list he keeps of Olympic athletes “sublime in their ineptitudes”: Byong Uk Il, a Korean boxer “who got so frustrated with himself that he began kicking at his opponent;” a Mongolian gymnast “dressed in robin’s egg blue” whose floor routine began with “the loud amplified click of a tape recorder being turned on;” and Quang Khai Le, a Vietnamese athlete who “started out last, stayed comfortably there, and finished last by twenty-six seconds” in his heat of the 1,500 meters. Guy Lawson’s “Hockey Nights,” about a cash-poor team in the Saskatchewan Junior Hockey League, whose players stand little chance of making it to the NHL and make fundraising appearances at local bingo games, points to the pressing need for more stories of rural minor league teams.

Rules of the Game is the more philosophical anthology. Bartlett Giamatti explains the appeal of soccer as lying “mostly in its denial of the use of the hands. For millions who work with their hands, there can be no greater relief than to escape the daily focus on those instruments of labor.” Rich Cohen (again), begins his 2001 “Boys of Winter,” an essay on aging athletes, with the line, “I used to dread the day when I would be older than the oldest athlete in the pros,” and describes a sports career as a “movement that, like certain pieces of music, simulates the lifespan, the growth and death, of the individual, and as such . . . is beautiful.” And in “Obsessed with Sport,” Joseph Epstein entertains a few popular explanations for why people watch sports before settling on his own: “The cast of characters in sport, the variety of situations, the complexity of behavior it puts on display, the overall human exhibit it offers—together these supply an enjoyment akin to that once provided by reading interminably long but inexhaustibly rich nineteenth-century novels.”

Gary Cartwright opens Rules of the Game with “Confessions of a Washed-Up Sportswriter,” a 1968 piece about working on the sports page at the Fort Worth Press. His colleagues included the well-known writer Bud Shrake, a “giant of a man” who once was “the accidental winner of a Chili Rice Eating Contest . . . while serving as a contest referee,” and the lesser known Puss Erwin, a retired postman who covered bowling and “hunched over his typewriter, drinking vodka from a paper cup.” Other colleagues would write Erwin’s stories for him when he was drunk, including one that offered a description of Kansas City Chiefs linebacker Sherrill Headrick as having “the face of an Oklahoma chicken thief.” (Headrick’s wife complained.) Cartwright makes it sound like an awfully fun place to work, but not every day.

Michael Rymer writes about education for the Village Voice and about books for Coldfront Magazine. He lives in the Bronx.