Reviewed:

Reviewed:

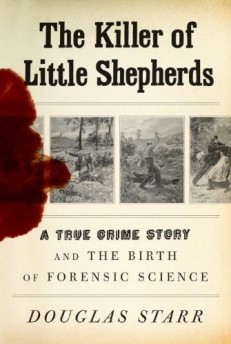

The Killer of Little Shepherds: A True Crime Story and the Birth of Forensic Science by Douglas Starr

Knopf, 320 pp., $26.95

Looking for a story, journalist Douglas Starr stumbled upon two great ones that dovetailed at the end of the 19th century: the murderous exploits of French serial killer Joseph Vacher and the pioneering criminology work of Dr. Alexandre Lacassagne. In a rare but forgivable moment of simplification, Starr juxtaposes his main characters:

In all of France there could not have been two men more different than Joseph Vacher and Alexandre Lacassagne. Vacher was wild, rootless, primitive, ruled by his impulses and sexual appetite. Lacassagne personified the bourgeois qualities of order, education, and dignity; he was regular in his habits, a voluminous reader, dedicated to service, restrained, and self-deferential. They were the opposite ends of the spectrum of human nature, as exemplified by a popular book at the time, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

In the first half of the book, before the two men cross paths, Starr alternates chapters between Vacher’s gruesome life as a vagabond and Lacassagne’s rise to fame. He doesn’t skimp on the gory details of Vacher’s crimes. Sent to an asylum for observation after a failed attempt to kill a woman he desired and then himself, Vacher, a former soldier, was released back into society less than a year after his botched murder-suicide. From 1894 to 1897, he killed at least 11 people. He roamed the French countryside, covering more than 600 miles by the time he was done, killing mostly young women and men, overpowering and repeatedly stabbing them.

Because of the geographical breadth of his crimes, and the lack of communication between law enforcement from town to town, it was some time before Vacher’s acts were linked together. Rural France is a character in the book as surely as the killer and the scientist, its quiet pathways turned menacing, its provincial villagers turned into close-minded mobs that would ruin the lives of wrongly accused suspects, its nighttime pastures the eerie backdrop of hasty, lantern-lit autopsies.

Starr deftly runs his narratives on their parallel tracks, and does an admirable job of bringing them together without sensationally exaggerating the neatness of their connection. It wasn’t Lacassagne who caught Vacher (that was a man who stopped him in the midst of an attack) or prosecuted him (that was magistrate Emile Fourquet). Nor did he create forensic science alone. Alphonse Bertillon, among others, played a key role, developing a system of identification that relied on measuring body parts and cataloging marks like scars and tattoos.

The Killer of Little Shepherds is deeply rooted in historical sources and subtle context, but Starr also has a journalist’s flair for the colorful detail. We learn that cadavers in Lyon were kept in a “floating morgue,” an unrefrigerated and leaky nightmare chained to a pier on the Rhone River. The old man who guarded it, and somehow lived on it full-time despite the stench, “seemed to have wandered out of the Old Testament, with his white beard and hair hanging down to his chest, a pipe clamped between his teeth, and his faithful little dog.” Near the end of the book, we meet an executioner named Deibler, who wasn’t considered “artistic” enough by a public that evidently wanted to be both bloodthirsty and decorous: “During his first appearance as chief executioner, Deibler created a maladroit impression. The convicted man struggled violently—so much so that Deibler had no choice but to grab him by the hair, bash his head repeatedly against the ground, and then position the stunned prisoner in the apparatus. After that, Deibler never could shake the image of seeming gauche.”

The mobs who watched the executions were unruly and perhaps a bit twisted, but Starr notes that less clamorous citizens were not immune to the lure of death. The river morgue in Lyon was the opposite of a state-of-the-art facility in Paris, where corpses were tipped “at a convenient viewing angle,” behind glass “similar to the display windows of the new department stores.” “People flocked in,” Starr writes, “whether or not they had missing relatives. Thousands strolled through every day to see the latest arrivals. Workmen came by on their lunch breaks, and retirees drifted in to occupy their time.”

Today’s display window is the TV, on which a group of very bad, very bloody programs have familiarized the American public with the latest in crime-fighting technology—the answers residing in the tiniest fibers, the spatter patterns of blood, the angles of wounds. Starr waits until the last few pages to directly address CSI, and he does a convincing job of arguing that the show’s outlandishly tidy plots have both exaggerated our scientific progress and perverted the work of real-life prosecutors and defense attorneys.

The 20th century saw an increase in the number of high-profile serial killers. Whether this was simply a matter of better reporting or an actual horrifying trend remains open to debate, but one thing is true—we remain as baffled by the deepest motivations of these killers as Lacassagne and his colleagues were a hundred years ago. Catching them (still a difficult thing to do in many cases) and understanding them are different tasks. Starr quotes the intellectual and anarchist Emile Gautier, who said, “What’s clear is that the most sophisticated science is still powerless to penetrate the mysteries of the human mind, which cannot be determined mathematically or by its chemical constitution, or by its molecular state.”

Even those who believe a clear, thick line can be drawn between good and evil must wonder at the reasons why people end up on one side of that line or the other. It’s this question that lurks throughout Starr’s riveting book.

John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.

Mentioned in this review: