Reviewed:

Reviewed:

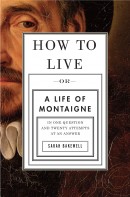

How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer by Sarah Bakewell

Other Press, 400 pp., $25.00

Michel de Montaigne is known among cat lovers for a popular quip: “When I am playing with my cat, how do I know that she is not playing with me?” This is just one of the musings in his Essays — a book that could qualify today as a blog, for Montaigne was the first person to unabashedly write about himself, flaws and all.

Accustomed to Facebook, Twitter and blogs, we take disclosure as a given. But in the 1500s, public self-revelation was reserved for great people who accomplished great things, or, like St. Augustine and Dante, those writing about how they found God.

Then there was Montaigne, who, in the Essays, characterized himself as “idle. Cool in the duties of friendship and kinship, and in public duties. Too self-centered.” Not exactly the hero type. Nor did he expound on the greatness of God. In fact, his fear that death is nothingness bordered on atheism.

Purposely evading the so-called big ideas, Montaigne homed in on the quotidian, at times mundane, details. In the Essays, he divulged that though he knew many fair ladies in his prime, he had never seen his wife’s breasts — not even during sex — out of respect for her honor; that he “could dine without a tablecloth, but very uncomfortably without a clean napkin”; and that he liked his meat rare. One of his most famous essays, “Of experience,” included a long-winded description of the pain of expelling kidney stones.

However, to dismiss Montaigne as a thinker on the grounds that his topics are commonplace is to ignore the precise genius of the Essays. In How to Live, Sarah Bakewell explains that focus on the workings of daily life is Montaigne’s philosophy, which can be encapsulated in the question: “How to live?”

It is crucial to note the distinction Bakewell makes between the question underlying the Essays and the moral dilemma — “How should one live?” — that has plagued so many from the ancient Greeks on. Montaigne does not care about “the good life” that Aristotle aligned with virtue. As Bakewell writes, “Moral dilemmas interested Montaigne, but he was less interested in what people ought to do than in what they actually did.”

Montaigne cared about how to most fully realize the life he had. The good life, by Montaigne’s pen, became the life well-lived. As he tells us, “You can tie up all moral philosophy with a common and private life just as well with a life of richer stuff.” His philosophy, at the risk of sounding New Age, encourages people to be themselves. By setting down his personal quirks and descriptions of conditions like vanity or fear of death, Montaigne captured what Bakewell calls “the experience of being human.”

On account of the essays’ universal themes and Montaigne’s affability, many considered him a kindred spirit. Blaise Pascal set the tone for many of Montaigne’s future admirers with his declaration: “It is not in Montaigne but in myself that I find everything I see there.” How to Live is about Montaigne and his life, but it is also about “Montaigne, the long party — that accumulation of shared and private conversations over four hundred and thirty years.”

The Essays garnered Montaigne a distinguished and disparate list of admirers, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Denis Diderot, André Gide, Stefan Zweig, Alexander Pope, Virginia Woolf, Laurence Sterne, and William Hazlitt — just to name a few. Each found in him the Montaigne they wanted to see. Zweig used Montaigne’s Stoicism to cope with his exile during WWII, Woolf pushed his stream-of-consciousness style further in her novels, and Hazlitt upheld him as a model essayist.

For the man whom everyone found him- or herself in, Bakewell writes a biography that reflects the Essays. How to Live is not a biography in the strict sense, and its unconventionality makes the book worthy of its subject. Instead of reciting Montaigne’s life in chronological order, Bakewell divides How to Live into “twenty attempts.” In calling her chapters “attempts,” Bakewell pays homage to Montaigne’s stylistic innovation of the essay, for the English translation of “essai” is “a trial, an attempt.”

Like Montaigne’s essays, which always ran away from their actual title, Bakewell’s chapters meander. In one, she digresses from her subject to a discussion of the modern-day “slow movement” in a manner that Montaigne would have undoubtedly enjoyed.

How to Live is a tribute to Montaigne, but Bakewell also lays bare a side of him that he tried to suppress — Montaigne the politician. By placing him in his political context, Bakewell exposes a Montaigne that is very much absent from the Essays. He presented himself as a disengaged citizen — he barely touched on his tenure as mayor of Bordeaux except to emphasize that he did it out of duty, not volition — in reality, he was embroiled in the French Wars of Religion. It is likely that the day after he wrote about the joy of being sequestered in his library, Montaigne rushed off to placate either the Catholics or the Huguenots. Yet this juxtaposition between the book and the man does not necessarily detract from Montaigne’s legacy. Instead, the insecurity makes him even more human.

Each of Bakewell’s 20 chapters ask the question of the title, and each is centered on an answer reflected in the life and work of Montaigne. Answers to how to live include “Don’t worry about death,” “Wake from the sleep of habit,” and “Do a good job, but not too good a job.”

Perhaps Montaigne himself would have answered “How to live?” with another one of his famous questions, “Que sais-je?” or “What do I know?” Although Montaigne’s skepticism is usually linked to the Greek skeptics, we can also recast it as the curiosity and wonder with which he approached life. Free of claims to knowledge, Montaigne wrote down everything he felt or noticed about himself.

After 21 years of writing, Montaigne recognized that his project of self-inquiry was part and parcel of who he had become. He admitted, “I have no more made my book than my book has made me.” It’s a notion worth remembering in our age, when the act of writing about oneself is hard to see as anything but solipsism. Montaigne and his essays provide a potentially more sympathetic take, and a potential guide for those on Facebook and Twitter. Our constant social networking is admittedly self-indulgent but, unbeknownst to many of the people doing it, it’s also linked to a rich philosophical tradition of self-inquiry.

Lucy Tang is a writer living in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker’s Book Bench, New York Magazine, and Brink.

Mentioned in this review: