Reviewed:

Reviewed:

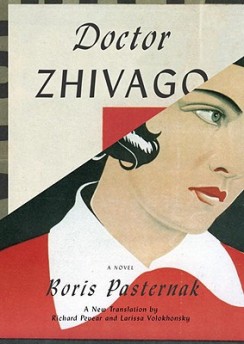

Doctor Zhivago by Boris Pasternak

Translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky

Pantheon, 544 pp., $30.00

The story behind the 1956 publication of Doctor Zhivago, and later film adaptation, is worthy of a book in its own right. Since the 1920s, Russian poet Boris Pasternak had been working on a novel. Bits of it had been excerpted, but Nikita Khrushchev’s government had suppressed publication of a full manuscript. In a feat of literary daring, an Italian journalist smuggled the manuscript out of Russia and published it in Italy. A year later, it was published in the United States. Unfortunately, the stilted and nearly purple prose of the translation by Max Hayward and Manya Harari made for an unpleasant reading experience. For more than 50 years, it was the only translation available to American readers, and partly for this reason, the reputation of director David Lean’s 1965 film version has long superseded that of Pasternak’s novel.

Lean’s sprawling adaptation galloped across the silver screen, and the story of Yuri Zhivago and Lara etched a place in the annals of epic cinematic romance, a trans-Siberian Gone With The Wind. Thanks to the film’s success, the name Zhivago evoked wintry landscapes, tear-stained declarations of love, and, of course, huge battles. The film had the right idea. Robert Bolt’s screenplay pared down the number of secondary characters and leaden political diatribe that so heavily weighs down the second half of Pasternak’s novel, without once sacrificing the epic quality of the story. As a result, the film offers a richer and far more satisfying experience than the novel. It still does.

There is now a Zhivago for the 21st century reader, translated by the husband-and-wife duo of Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, whose editions of Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and others has made them perhaps the only current-day superstars in the translation field. Unequipped to comment on fidelity to the Russian, I can say the prose of this Zhivago is, at minimum, far more lucid and artful than the result of the Hayward/Harari collaboration.

The novel opens on a young, recently orphaned Yuri Zhivago. His one familial connection is an uncle — a laconic priest who has parted ways with the church because of his radical political leanings, and who imparts these political and philosophical beliefs to Yuri. The uncle pawns Yuri off on the Gromekos, a moderately wealthy family with a young daughter, who will eventually become Yuri’s wife. This is one of two women who will permanently alter his life. The other, Lara Antipov, he first sees when she accidentally shoots the wrong man at a Christmas party. Years later, they are thrown together as medical personnel on the front lines. In times of tragedy and privation, their love blooms, and Yuri finds himself torn between wife and lover. This jockeying occurs in one capacity or another for the fraught remainder of Zhivago’s life.

Pasternak’s work is a different kind of Russian novel, and illustrates a different kind of Russian experience. In Pevear’s introduction, a cogent consideration of the book’s merit, he explains what separates Zhivago from preceding Russian novels:

Doctor Zhivago had necessarily to be an experimental novel. But it is not experimental in a modernist or formalist way . . . Pasternak’s vision is defined by real presence, by an intensity of physical sensation rendered in the abundance of natural description or translated into the voices of his many characters.

The importance of the relationship between “real presence” and “natural description” cannot be overstated. The novel opens on a young Yuri Zhivago witnessing the funeral of his mother. Yuri slowly realizes he is orphaned as “a handful of earth, a rain of clods” separates his mother’s body from his own. Almost immediately after, a blizzard fills the air and ravages the land. Yuri’s attention is held captive by the power and ominous majesty of nature. This continues until the end of the novel, which closes with a set of Zhivago’s posthumously published poems, which have titles like “Wind,” “A Winter Night,” and one of the last, “The Earth.” Zhivago’s almost Whitmanesque attention to and affection for the natural world is what characterizes the humanistic viewpoint, which he develops continually throughout the novel, in spite of hardship, war and political oppression. He cries, yearns and emotes far more than the Russian protagonists of the 19th century.

Zhivago’s emotionalism sets him apart from the less compassionate, almost cartoonish villains in the novel; but it also renders him unable to function responsibly. He grapples with feelings of obligation to those around him, whether as doctor, husband or father. He is moralist first, pragmatist second, and resorts to action last. Although a man of science and empiricism, he primarily relies on feelings or mental response in times of strife. By the end of the novel, he has left behind three women and a passel of children.

Unlike earlier, more formally rendered Russian novels, Zhivago is a novel in scenes. This is simultaneously its most interesting and frustrating quality. It is divided into two books, each chapter divided into several sections. The characters are unveiled gradually and inconsistently. There is a kind of postmodern, haphazard quality to the trajectory that yields a bumpy journey. The first half of the book is dedicated to a gradual uncovering of character and theme, while the second half is weighed down by a long, didactic, and indirect history of Russia’s revolutions and civil wars. Fortunately, in the Pevear and Volokhonsky translation, the reader has a better chance of following the multi-arc, multi-voice tapestry of suffering occasioned by Russia’s bloody history. If the story is not considerably more enjoyable than in the first translation, it’s certainly clearer. If you hope for more, watch the movie.

Joshua Zajdman holds a B.A. in English, an M.A. in Literary and Cultural Studies, and a book at all times.