Reviewed:

Reviewed:

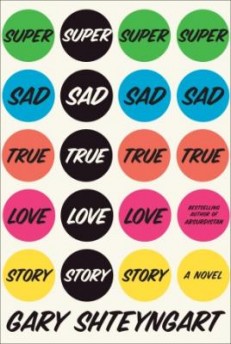

Super Sad True Love Story by Gary Shteyngart

Random House, 352 pp., $26.00

In Super Sad True Love Story, his third novel, Gary Shteyngart largely sticks to what has become his patented formula: take one hapless underdog type; place him in somewhat dystopian but recognizable circumstances; involve him in a bizarre, improbable scheme that seems at first to demand too much of him but finally inspires him to become a better person; include a lot of sharply observed, wryly phrased detail; let the whole thing run its unstoppable picaresque course.

Shteyngart first unveiled this model in The Russian Debutante’s Handbook. There, our schlemiel was Vladimir Girshkin, a luckless embarrassment to his striving immigrant parents, comically embroiled in the Ponzi-scheming of The Groundhog, a ruthless mafioso running amok in Prava, aka Prague, aka “the Paris of the ’90s.” All Vladimir really wants is approval, which is to say love, which is to say that underneath the keen and genuinely funny satire, Handbook was a touching, even sweet story, balancing its tartness with charm. Shteyngart’s follow-up—Absurdistan—perfected the blueprint, stressing the insider/outsider credentials of its obese protagonist, Misha Vainberg, son of a recently murdered oligarch. The sins of the father are visited on his unfortunate son, who is denied the American visa he so desperately needs to make his way back to the South Bronx and his girlfriend. Like Vladimir, Misha desperately wishes to prove himself, and he manages to do so, not in spite of but because of his ineptness. The novel succeeds as politico-historical lampoon, bildungsroman, and guileless love story all at once.

Because the whole thing works so well, it’s hard to blame him for returning to the basic set-up. Super Sad True Love Story is written by a sure hand, a novelist fully confident in his considerable abilities, writing as if he has nothing to prove. The novel feels effortless, but it is also a carefully mapped work, equipped with a framing device, a built-in mythology, a language and a politics (both public and private) all its own. Super Sad is rollicking fun, and the narrative rarely swerves or strains under the weight of its ambition. The balance of design and execution here is no small accomplishment.

Set in the near future, Super Sad relates the intertwining stories of Lenny Abramov and Eunice Park, two drifting American souls who meet in Rome. Lenny—“a nervous, average man sixty-nine inches in height, 160 pounds in heft, with a lightly dangerous body mass index of 23.9”—is in Rome as the Life Lovers Outreach Coordinator, on a mission to locate High Net Worth Individuals (or HNWIs) for Post-Human Services, a recently acquired division of Staatling-Wapaching Corporation. He encounters Eunice—a newly minted graduate of Elderbird College, with a major in Images and a minor in Assertiveness— at a party, immediately falling head-over-39-year-old-heels for her brand of petulant, youthful charm. Improbably but inevitably, Eunice, whose de rigueur shallow consumerism masks an earnest desire to help others, responds to Lenny’s awkward attempts to woo her, and the two are soon shacked up in the “740 square feet that form [Lenny’s] share of Manhattan Island.” Their tentative, frequently disastrous stabs at intimacy in a world that has long since dismissed intimacy as ridiculously outmoded are chronicled in chapters alternating their points of view.

Though Lenny and Eunice split narration duties, strictly speaking, their perspectives are not equally privileged: Lenny’s side of things is related in his diary entries; Eunice gets her say in snapshots ostensibly taken from her “GlobalTeens” account, a MySpace/Facebook hybrid, where she is known as “Euni-Tard.” Her pronouncements are thus presented alongside communiqués from her friend Jenny Kang (GlobalTeens handle: “Grillbitch”), her sister Sally, and her mother, whose Korean-inflected pidgin English, for which she is perpetually apologizing, is a startlingly tone-deaf touch. (Shteyngart has never been interested in political correctness, and his willingness to dispense with the niceties lent his previous novels a sincerely anarchic nonchalance, but his rendering of Mrs. Park’s speech comes off as unnecessarily mean-spirited; meanwhile, Lenny’s Russian-immigrant parents, who occasionally speak their own version of accented English, are mostly spared communications-related indignity, permitted Russian asides that are translated parenthetically.) The upshot is that we finally know and understand and sympathize with Lenny, while Eunice remains far more opaque.

The love story unfolds against a background that assures its super-sadness: in an Absurd-America, the currency has collapsed (the dollar is now yuan-pegged and otherwise worthless), the army is losing a war in Venezuela, Low Net Worth Individuals (LNWIs) are setting up tents in city parks, while HNWIs are mainly preoccupied with their Credit and Fuckability ratings, emitted by the “äppäräti” carried by one and all, constantly “buzzing with contacts, data, pictures, projections, maps, incomes, sound, fury.” And no one reads books, those “printed, bound media artifacts,” which are said to smell, though of course “no one” does not include Lenny, whose fear of mortality—“Today I’ve made a major decision: I am never going to die,” begins his first diary entry—collides with the demise of America’s global superpower.

At the end, I may have wished that some of the questions the novel raises could have been answered more sincerely, not just as punch lines. Shteyngart’s brand of satire works best when the full stakes—emotional, intellectual, familial—are accounted for, when issues of selfhood and statehood are more earnestly bound up with the jokes. But the novel, committed as it is to spirited good times, demonstrates the continued power of Shteyngart’s formula.

Yevgeniya Traps is a doctoral candidate in English at the Graduate Center-CUNY.

Mentioned in this review:

Super Sad True Love Story

The Russian Debutante’s Handbook

Absurdistan