Reviewed:

Reviewed:

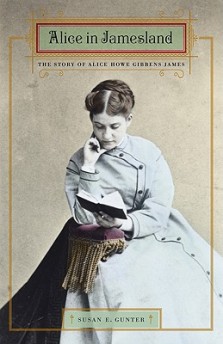

Alice in Jamesland by Susan E. Gunter

University of Nebraska Press, 464 pp., $50.00

Susan Gunter’s Alice in Jamesland, published last year, is the first biography of Alice Howe Gibbens James, wife of William James. The book’s title hints at the fact that its subject is of most interest in context, as a traveler in one of the most famous families in American history. Alice was an “idealistic and fundamentally serious young woman,” whose ancestors “led narrow lives of service, piety, and rectitude.” William was 34 when they met, and she was 27, but her life had given her “a maturity hard-won.” When she was 16, her father, a physician, had committed suicide, leaving Alice in charge of her siblings and a devastated mother.

James was legendarily ambivalent about the relationship, “subjecting her to a courtship so bizarre, tormented, and tormenting that it is a wonder the two ever married.” But this seemingly had more to do with James’ inability to make up his mind than with his affection for Alice, which ran deep: “Sometimes, he thanked her just for being born.”

When the two were married, Alice served as a bond between William and his novelist brother Henry, one of the most compelling plots in Gunter’s book. Alice had an “unmitigated appreciation” for Henry’s work, an enthusiasm that eluded William. She made sure the brothers remained in close contact, and she also served as an advocate for Henry’s fiction. One moving scene has her reading The Spoils of Poynton to William as he falls asleep at night.

If the book is a bit academic in nature—heavily footnoted and sometimes workmanlike in the way it synthesizes other sources—it does shed light on the selfless life of Alice (“if my existence is to justify itself,” she wrote to Henry, “it must be through other lives”) and her influence on the life and work of her husband. For one thing, she held a strict belief in God, and often advised William to do the same. (William once charmingly responded, “[W]ith you for his prophet, what god would not prevail in the long run.”) It’s impossible to exactly measure her influence, but her strong feelings about religion and her thoughts about the supernatural (she tried to contact William after he died) must have had an impact on James’ interest in same.

Viewing William James through the prism of his marriage deepens a sense of his occasional emotional awkwardness. Reading about him in other books, one often senses an ebullience that feels infectious even on the page—but examining him closely as husband and father provides an idea of how maddening he could be as well. For one thing, he was constantly leaving right after Alice gave birth, rationalizing that things would be easier for Alice with him out of her hair. Once, after Alice had delivered an 11-pound son, William told Henry, “It all went off most beautifully—One doesn’t see why it mightn’t happen every week.” He could also be ridiculously off-key when he thought he was simply being honest. At one point, with husband and wife separated, he felt that his affection for a maid might lead to an urge to kiss her when she left. He wrote to Alice: “In fact I should be less than human and unworthy to be your or any one else’s husband without such an impulse on that occasion. Wherefore send your consent, so that if it takes place [the kiss] it shall be with a good conscience.”

Alice James shared a name with William and Henry’s delicate sister. But while she was prone to occasional depression, her mostly hearty make-up was a welcome corrective to the sometimes crippling neuroses of the family into which she was folded. Gunter makes the point that William’s wife was not involved with the nascent feminist movements around her: “She refused to let herself think of what she might have achieved on her own.” This quality made for a character that doesn’t lend itself to much narrative momentum in a biography, but the close view of 19th-century domesticity and Alice’s role in an endlessly interesting clan makes Gunter’s book a welcome addition to the James family literature.

John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.