Reviewed:

Reviewed:

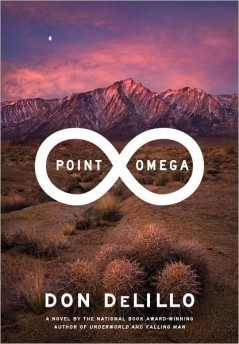

Point Omega by Don DeLillo

Scribner, 128 pp., $24.00

Ernest Hemingway once advised writers to “eschew the monumental. Shun the epic,” he said. “All the guys who can paint great big pictures can paint great small ones.”

Don DeLillo has painted his share of panoramas. White Noise went to the heart of our love for things and fear of death; Underworld, with its ominous cover art of a bird flying toward the World Trade Center, is a wide-angle vision of postwar America, capturing in its exacting gaze everything from baseball to nuclear dread.

But more recently, DeLillo has taken Hemingway’s advice too closely to heart. His books have been shrinking: the great big canvases of the ’80s and ’90s have become small, ornate miniatures that do not easily give up their secrets. The average length of his last four novels—The Body Artist, Cosmopolis, Falling Man, and now Point Omega—is 188 pages. Underworld, by contrast, was 832.

It isn’t only the page count that has diminished in DeLillo’s recent work. The rituals of death in our media-saturated society have long been a central concern in his fiction. In White Noise, for example, the Hitler Studies professor Jack Gladney says, “I’ve got death inside me. It’s just a question of whether or not I can outlive it.” But in DeLillo’s finest works, existential dread is coated with enough dark humor and narrative thrust—in the case of White Noise, the most photographed barn in America, the Airborne Toxic Event, and Jack’s search for Dylar, a pill that will quell his death anxiety—to keep the reader grounded.

Lately, however, DeLillo’s desire to construct full-scale novels around this philosophical concern has waned, and what remains is a singular, uneasy fixation with the progression of time. Philip Roth, who is three years older than DeLillo, has also devoted his most recent fiction to a full-on grappling with mortality. Of the great mid-century novelists now in their 70s, only Thomas Pynchon seems to be approaching old age with good cheer: his last protagonist was a chipper, perpetually stoned private eye.

DeLillo’s narrowed thematic interest has been joined by less imaginative plots. Whereas in Libra DeLillo brashly rewrote the narrative of the JFK assassination (George Will, in an infamous review, called it “literary vandalism”), Point Omega barely has a structure: filmmaker Jim Finley travels to the California desert in order to interview Richard Elster, a “defense intellectual” who was one of the architects of the Iraq War. For most of the book, they sit on Elster’s porch, drinking and pontificating. Elster’s daughter, Jessie, comes to visit. She abruptly disappears. There is little other action to speak of.

Based on his extensive, vatic ramblings, it would be unwise to trust Elster with a grocery list, much less a military campaign. Supposedly a neo-conservative theorist of the sort Cheney and Rumsfeld courted, he seems to have taken far more interest in literary theory than anything resembling foreign policy:

“We’re all played out. Matter wants to lose its self-consciousness. We’re the mind and heart that matter has become.”

“It’s different here, time is enormous, that’s what I feel here, palpably. Time that precedes us and survives us.”

“We expand, we fly outward, that’s the nature of life ever since the cell. The cell was a revolution. Think of it.”

Unrelated to any narrative developments, this sort of thing threatens to alienate readers who aren’t familiar with, say, Henri Bergson’s theories on the metaphysics of time. What’s more, it’s heavy-handed and smacks of a pretension that was absent from DeLillo’s best work. It’s not often that a book of 128 pages feels unwieldy, but this one does from start to finish.

The novel begins and ends with protracted analyses of “24 Hour Psycho,” a video installation by Douglas Gordon in which the film Psycho is slowed down to play for 24 hours. DeLillo dwells far too long on this piece, as if its meanings about the passage of time, violence, media, and mortality weren’t painfully obvious. These are big questions, all. But when those questions are presented as exposition, the result is a lecture, not a novel. Even the book’s title is ominous: I’ll leave it alone and just direct readers to the same Wikipedia page every reviewer will surely peruse.

Some years ago, having just finished college, I found DeLillo’s address in the database of the publishing company I was working for and sent him my senior thesis, in which I analyzed the role of mortality as an ethical agent in his work. He was gracious enough to send back a reply, though I don’t think he slogged through the whole affair.

I’ve lost his address since, but were I to write to him again, the message would be much briefer: tell us a good story again.

Alexander Nazaryan has written about books for the New York Times Book Review, the Village Voice, the New Criterion, Salon, and other publications. He is completing a novel about Russian organized crime.

Mentioned in this review:

Point Omega

White Noise

Underworld

Libra

Cosmopolis

The Body Artist

Falling Man