Reviewed:

Reviewed:

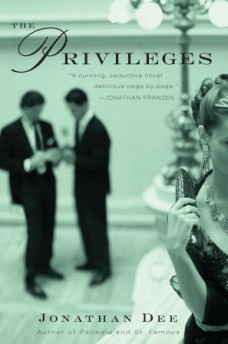

The Privileges by Jonathan Dee

Random House, 272 pp., $25.00

The New York Times recently reported on certain Pittsburgh weddings where guests help themselves to a smorgasbord of thousands of cookies, of many ethnic varieties, usually baked by the bride’s family. The Pittsburgh wedding that opens Jonathan Dee’s fifth novel, The Privileges, does not have cookies—neither of the happy couple’s families are truly from the city. But the novel is nonetheless fantastically keyed in to the tangible and intangible details, the social patterns and expectations, that the cookie article and others like it document and that collectively make up—as the New York Times Magazine, where Dee is a staff writer, titles its front section—The Way We Live Now. Emphasis on a particular we.

Adam Morey works in Manhattan finance: first in private equity, later at a hedge fund. Adam’s wife, Cynthia, buys their daughter, April, Tory Burch shoes, and becomes the kind of young mother who gossips with her daughter’s friends while maybe, pathetically, thinking she is one of them. The couple’s son, Jonas, is an angry adolescent who prefers old-school punk rock to the indie tunes beloved by the music snobs, the ones “flunking English because they spent so much time commenting on one another’s blogs.” Flunking English, that is, at Dalton, the famously tony prep school on the Upper East Side. The Moreys’ rise is the novel’s plot, and it is intimately connected to the financial bubble of the past decade.

At the novel’s start, all that distinguishes the Moreys is that they are marrying young (just graduated from college). “This is how she and Adam figured in the lives of their friends,” Cynthia thinks, “as the fearless ones, dismissive of warnings and permissions, the ones who go first.” But a brisk 200 pages and 25 years later, they are utterly exceptional by way of their astounding and self-made wealth, their philanthropy, and their poise. The Moreys are an exemplary version of the way we live now, perhaps as individuals but certainly as a society. In a word, they are overleveraged.

The book’s four sections depict different stages of their ascent—wedding; young parenthood; burgeoning success; and, finally, top of the world—and though we are not shown what happens in between these epochs, it never seems implausible that the Moreys, given what we know about them, have managed to so audaciously amass. For a novel with its ambitions, The Privileges is unusually free of self-consciously filigreed prose. Dee captures his characters’ thoughts without straining for exact diction or rhythm, while still making one feel, at times, completely immersed in this decadent world. It moves along jauntily, really just a collection of set-pieces, few taking up more than ten pages. Particularly choice among these are the Moreys’ day trip to the Connecticut country house of Adam’s boss; April’s time at the sort of insane New York City high school party that you really hope exists; and Jonas’ quiet competence and success as a University of Chicago undergrad.

The members of the Morey nuclear family are—by their own design as well as their creator’s—the only four characters worth more than a moment’s thought. Adam and Cynthia’s merciless focus on improving their material lives is their defining quality. Even at seven years old, April senses this: she “felt as if her family came from nowhere, and, more puzzlingly, that this suited her parents just fine.” And here’s Adam:

It wasn’t enough to trust in your future, you had to seize your future, pull it up out of the stream of time, and in doing so you separated yourself from the legions of pathetic, sullen yes-men who had faith in the world as a patrimony. That kind of meek belief in the ultimate justice of things was not in Adam’s makeup. He’d give their children everything too, risk anything for them. He knew what he was risking. But it was all a test of your fitness anyway.

Speaking of patrimony and fitness: Adam’s father dies of a heart attack at a relatively early age, planting in Adam the kind of death-fear you often read about in Great Men. Adam becomes compulsive about exercise and stewarding his freakishly healthy body (“he wasn’t growing more distinguished as he aged—it was more like he wasn’t aging at all”). In a hotel suite for a night of lovemaking without the kids around, he makes sure to check for a defibrillator. And when he’s told he can inherit an executive partnership at his private-equity fund, Adam hesitates, and then refuses: “It was unsettling even to think of money in terms other than those of growth, of how it might be used to make more money. Something about it smelled of death to him but he didn’t know why.”

Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now, published in 1875, has at its center a prospective railroad in the southwest United States whose value, thanks to sophisticated finance, is predicated not on the thing itself but on what a speculator in London is willing to give you for your share of it at any given moment. In Dee’s world of finance, too, there are “ethereal instruments,” which “were like some brand of astrophysics that generated money. . . . the ethereal was where the real money was, and everybody knew it.” These are those instruments you’ve been reading about since September 2008.

Adam does commit financial crimes—for a while, he runs an insider-trading scheme—but he makes his real riches the perfectly legal way, by inflating the bubble and making money out of money, largely in the “ether.” This should sound familiar. What crashed the Dow, crippled the credit markets, and caused the worst recession since the 1930s were not crimes, but rather the condoned mentality that allowed individuals and institutions to perpetually leverage what they had to obtain things they didn’t, while acting as though this plainly unsound practice—one that assumed eternal and nearly unfettered growth—was not only sustainable but responsible. More than Bernard Madoff, the symbol of the mid-oughts are the millions of people who kept hopping from house to bigger house because, as Dee notes of the Moreys’ adventures in real estate, “They’d made a fortune each time they’d sold.”

Money is not the only thing the Moreys leverage. Youth is the prime asset—the foremost of the privileges—and, as Adam pinches his blubber-free stomach and Cynthia considers plastic surgery, you see that they have leveraged this, too. They have leveraged their spirits, waylaying those whispers of mortality that are the birthright of the rest of us by concentrating on getting and spending more and more money. The Moreys even celebrate their silver anniversary after 23 years, borrowing those two extra years against the collateral of total faith in their union’s longevity.

Their children are the prime victims of the couple’s borrowing binge. April, the elder, is a nightmare: an empty socialite, a reckless drug addict who is lucky still to be alive. Jonas would seem at first to be the reverse: well-adjusted, bright, curious. But he has inherited his father’s sickly revulsion for inheritance—“No one could help what they were born into. You just had to start from zero and not let it determine who you were”—and one fears, if not for him, then for his kids.

At novel’s end, and excepting April’s mess, which doesn’t appear to faze them, the Moreys are parodies of fortune. Adam’s hedge fund is about to go public. Cynthia’s philanthropic tentacles have never stretched wider. The novel presumably closes in the present day, but Adam has not been subject to the decline, in either market capital or public esteem, that most Masters of the Universe have suffered over the past two years. In this light, The Privileges reads like a Greek tragedy without the tragedy.

But if you don’t think that the Fall is on the way, then you are as blinkered as the Moreys are. Cynthia gets her taste of it in the novel’s final section, as she watches the death of her father. The very setting (and this is one of Dee’s most biting touches) is a cruel rejoinder to Cynthia’s way of thinking: he has chosen to die in a hospice, a place specifically designed not to postpone death but to roll out the red carpet for it. For Cynthia, death, like all obstacles to future growth, is to be ferociously opposed:

She wished the bed, or the room, or the place itself, was unsatisfactory in some way she could see, so that she could inquire nicely or pitch a fit or even just donate some money and cause it to be improved. But everything here seemed perfectly suited to its purpose.

A Morey has finally encountered something she can’t overcome. And it occurs to the reader—as this notion perhaps taps on the door even of Cynthia’s money-guarded mind—that neither she nor Adam will fend off death, either. The Privileges doesn’t need to depict the Moreys’ comeuppance: when you seek as much as they do, your failure to get it is guaranteed. Like all bubbles, life is not sustainable over the long run.

Marc Tracy is a staff writer at Tablet Magazine.

Mentioned in this review: