Reviewed:

Reviewed:

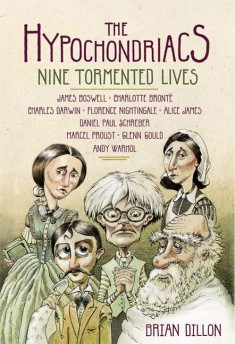

The Hypochondriacs: Nine Tormented Lives by Brian Dillon

Faber & Faber, 288 pp., $25.00

No one is healthy all of the time.

Health is a condition that tends toward malfunction and failure. Our bodies betray us daily, then aging takes over, and the weeks and years literally chip away at us. The body is a carapace, subject to external invaders and internal breakdown. Eating leads to gas or heartburn. Skin blemishes. Muscles fatigue. Eyes strain, backs become sore, hair falls out, gums recede, teeth rot. Minor illness strikes and noses stuff up, fevers rage, stomachs regurgitate, bodies ache. More seriously, hearts attack; gallbladders and kidneys form stones; cells mutate into cancers that spread uncontrollably; organs fail; lungs fill with fluid; blood clots and fails to circulate. Despite all this, the idea that perfect health is within our grasp remains a potent fantasy, fueled by an industry which plies us with goods and services designed to make our lives both longer and more robust, from Yogalates to Jamba Juice. But the fantasy of even adequate health is impossible if you are a hypochondriac.

The question of who is a hypochondriac is extremely vexed. Brian Dillon’s new study, The Hypochondriacs, tries to work through the shifting meaning and common threads in the lives of nine “hypochondriac” writers and artists from James Boswell to Andy Warhol. We learn bits about the constantly evolving definition of hypochondriasis, though it is sometimes awkwardly couched within these biographies, and we are told about select moments in the lives of each of Dillon’s subjects: Boswell, Charlotte Brontë, Charles Darwin, Florence Nightingale, Alice James, Daniel Paul Schreber, Marcel Proust, Glenn Gould, and Warhol. Yet the book, like its subjects, spends too much time in the conditional and the hypothetical: there are too many suppositions and what ifs? For instance, Brontë might have been a hypochondriac because her “apprehensive” heroine—excessive apprehension or worry being a trait associated with hypochondria—Jane Eyre, was called one by Rochester on the eve of their wedding. Of course, readers of the classic will remember the madwoman in the attic Rochester was hiding. Thus Jane had every reason to worry about her impending marriage. Is it hypochondria when you are right?

Dillon’s introduction opens with a description of the modern hypochondriac, who is always someone else. “Hypochondriacs are almost always other people: few of us care to admit to the levels of delusion and self-regard that we depreciate in the hypochondriac.” Yet they are everywhere. Dillon insists, “We all know at least one,” and he offers himself up as proof, haven fallen victim to the malady after his parents both died when he was young. The hypochondriac, “is that person who suspects that an organic disease is present in his or her body—occasionally, the suspicion concerns mental illness, or even hypochondria itself—when there is no medical evidence to support that opinion.” In fact, the hypochondriac often, “does not actually seek medical advice or treatment, or even reassurance that he or she is well, but rather an unassailable certainty. It may even appear that for the hypochondriac the solidity of a real disease is preferable to the fog of optimism and uncertainty that passes for most of us, most of the time, as good health.” In this line of thinking, hypochondriasis is a type of anxiety disorder, related to anorexia and body dysmorphia. The hypochondriac’s “fear is fundamentally a mistake, an error in his or her apprehension of the body and its relation to the world” such that the “pattern of such suspicions [is] almost a career.” Thus the hypochondriac prefers worrying about his health to knowing what the state of his health actually is, and avoids doctors who might offer reassurance because he prefers luxuriating in the certainty that something is wrong. He is convinced his body is diseased and organizes his life around this principle.

Several of Dillon’s recurring themes are contained in this definition: the fraught relation between the hypochondriac and the body, hypochondria as mental illness, and hypochondria and—or as—work. Dillon’s argument also revolves around hypochondria as control, a way of structuring time. James Boswell, Dillon’s first case, proves this point: “His problems were temporal and textual, his illness a matter of irregular habits of body and mind, and its cure close at hand in the form of his books and his own diaries. His hypochondria, as he learned to call it, was bound up, in short, with the time he spent, or did not spend, reading and writing.” Dillon cites plenty of evidence for Boswell as an anxious, manic planner who can never stick to his schedules, without which he falls into idleness and depravity. His great fear, Dillon writes, was that he would “‘dissolve.’” This was “more than a metaphor,” as Boswell had a real dread of “becoming formless, friable or liquid, a character without distinct lines, a soul without design, a body without borders.” This is telling, as “a character without distinct lines” is not a bad description of a biographer, which is how Boswell eventually made his name. Dillon’s history meshes nicely with his biography in the Boswell section: the experts of the day he cites describe a figure very much like Boswell, and their identification of hypochondria with “English” vices—especially with the excess and luxury endemic to upper-class life in the eighteenth century—jibes with the Scottish Boswell’s self-excoriation for sloth, for chasing (and catching) loose women, and for indulging his melancholia.

But while he succeeds with Boswell, elsewhere Dillon has a penchant for tangents and judgments that seem irrelevant, sometimes even outrageous. For instance, in the middle of the Florence Nightingale chapter we are treated to a description of how the nineteenth-century figure of the dandy shared with the contemporary Victorian woman hypochondriac “nothing less than an intense, even sickly, awareness of one’s own corporeal being.” Provocative, but huh? Nightingale was not a typical Victorian woman: she was a nurse obsessed with reforming conditions in war hospitals, and hardly comparable to a man obsessed with being seen in the latest fashions. Furthermore, most of Dillon’s points about Nightingale either rely on the work of previous biographers (particularly Lytton Strachey) or arrive as proclamations from nowhere. His statement that Nightingale was “a monster of self-belief, self-delusion and expertly deployed enfeeblement” could be applied to any number of his hypochondriacs, but feels misogynist in this particular case: he certainly proves the same of Glenn Gould, Charles Darwin, and Andy Warhol, none of whom are dubbed “monsters.” Dillon seems to stir in his history and his opinions willy-nilly, making his nine “biograph[ies] of bod[ies]” lopsided and of erratic quality.

Dillon first posits hypochondriasis as a mode of self-discipline and self-knowledge with Boswell and recycles it frequently in other case histories. Darwin also lived by elaborate schedules which he thought could regulate his health, or at least his anxiety about it. Crucially, Dillon just gestures to Darwin’s “real suffering;” he is so eager to make Darwin an emblematic Victorian that he dismisses his pain in favor of cultural explanations and rationalizations. He describes Darwin’s illnesses several times, and remains unmoved: “He was tortured by anxiety, and suffered vomiting, flatulence, fainting sensations and black spots before his eyes.” His attitude here and in other sections where his subjects have real ailments, properly diagnosed or just hypothesized—Alice James’ breast cancer, Florence Nightingale’s possible Brucellosis, Andy Warhol’s untreated hernia—is to shrug and let the real biographers fight it out. His lack of human sympathy startles, perhaps proving that hypochondriasis is, above all else, a disorder of selfishness, an inability to acknowledge the pain of others.

To puzzle this out, perhaps for Dillon to leave the state of hypochondriasis and enter the world of actual suffering would be to relinquish control of his subjects, and there is a complex relationship between hypochondriasis and control. Boswell and Darwin’s mania for schedules aside, hypochondria is also a self-sanctioned loss of control, admitting that the body has a will of its own, that we are governed by its demands and subject to its whims. It is immaterial to Dillon whether Darwin had or simply fantasized about unremitting flatulence, nausea, boils, constant fear, and a “shivering and shaking sensation,” yet it mattered a great deal to Darwin, and Dillon should explore the distinction. Isn’t this an element of hypochondria, distinguishing real from fantasy? Furthermore, Dillon never acknowledges that his subjects’ real wish is for health to remain a problem. The hypochondriac is intensely interested in pain, but not in the experience of it: he wants to think about it, for something to be wrong. The hypochondriac’s greatest desire is for bodily chaos. Without that, his worries become realities, and their potency as worries qua worries is lost.

In his essay “Worry and Its Discontents,” psychoanalyst Adam Phillips writes that we know ourselves through worry. “Worries, unlike dreams, thoughts, and feelings are something to which we give agency. We can, with the irony that characterizes the defenses, allow them to be beyond omnipotent control, whereas for dreams we claim authorship. We can be worried, but we can’t be dreamed.” Through worry, the hypochondriac gives his precarious health precedence over his life. Moreover, Phillips writes: “All of us may be surrealist in our dreams, but in our worries we are incorrigibly bourgeois.” Hypochondriasis is as bourgeois as worry gets: anyone who really had to get on with life could not indulge in the wheel-spinning of the hypochondriac; it requires leisure, time, space.

Like the definition of hypochondria, Dillon’s timeline is very hard to pin down. He suggests hypochondriasis “became fashionable” in the nineteenth century as a “catch-all for slippery cases,” like melancholia had been in the seventeenth century and hysteria would be in later years. Elsewhere Dillon writes, “In its most dramatic and richly imagined forms it seems even to have defined a later version of the Gothic imagination and a vision of the creative temperament stymied, isolated or in exile.” This, too, is stubbornly unclear, as “Gothic” could easily be changed in this sentence to “the Romantics,” who had a similar notion of creativity. Susan Sontag claims that “the Romantics invented invalidism as a pretext for leisure, and for bourgeois obligations in order to live only for one’s art,” the same claims Dillon makes for hypochondria in the Gothic period.

As for the Victorians, Dillon asserts they were all more or less hypochondriacs, such that the description “starts to look like a character type rather than a set of discrete symptoms.” He diagnoses some “cultural illness” which overlapped significantly with hypochondria. Not only Darwin suffered from the hypochondriac’s constellation of ailments, but so did his fellow hydrotherapy enthusiasts Lord Tennyson, Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, Thomas and Jane Carlyle, and George Eliot, the last of whom had contemporary symptoms of hypochondriasis, including headaches, dyspepsia, frequent colds, fatigue, swimming head, influenza, aching limbs, melancholia, and streaming red eyes. However the popularity of hydrotherapy and hypochondria-as-a-cultural-illness trope doesn’t hold water, since Dillon’s use of the term is so malleable. His final hypochondriac, Andy Warhol, is emblematic of his—and therefore our—age: “We now live at a time when Warhol’s fears are emphatically our own—weight, complexion, age, aesthetics, the virulence of the new diseases and the efficacy of the old ones—but they ought to remind us of the fears of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.” The way the book is constructed, around such a fuzzy concept, naturally they do. Is the point, then, that hypochondriacs are like the poor, always with us in some form? Or is hypochondriasis some kind of superbug, adaptable to any environment?

Perhaps some other writing about illness will shed some much-needed light on Dillon’s shadowy figures and hazy conclusions. Susan Sontag’s 1978 study, Illness as Metaphor, makes the problems with writing about illness explicit. If Dillon has taken on a difficult topic, Sontag’s is even tougher. She is attempting to describe the “punitive or sentimental fantasies” we have about the ill on a general level. She traffics in anti-hypochondria, refuses to indulge in the endless thinking, wishing, dreaming about illness that Dillon’s nine subjects cannot help but do. She is especially trenchant on how the ill are judged by society, that illness is seen as a failure, a moral blemish, a punishment, something the superior person can “master.” In this sense the sick person—and the hypochondriac as well—is a kind of outlaw, or scofflaw—“disease imagery is used to express concern for social order, and health is something everyone is presumed to know about” and therefore able to achieve. By forsaking health intentionally the hypochondriac is doing something unnatural, subverting the social imperative to live a productive and healthy life. In one of Sontag’s own metaphors, we all have “dual citizenship” in the “kingdom of the well” and the “kingdom of the sick.” Choosing to live in the latter, as Dillon’s hypochondriacs do, is proof of the virulence of their disease.

Virginia Woolf spent most of her life in the kingdom of the sick. Her essay about time there, On Being Ill, which Dillon cites in his chapter on Nightingale, comparing the women who both retreated to their rooms in order to work, was first published in 1926 and remains one of the most moving and empathetic descriptions of that place. It begins by asking a critical question:

Considering how common illness is, how tremendous the spiritual change that it brings, how astonishing, when the lights of health go down, the undiscovered countries that are then disclosed, what wastes and deserts of the soul a slight attack of influenza brings to view, what precipices and lawns sprinkled with bright flowers a little rise of temperature reveals, what ancient and obdurate oaks are uprooted in use by the act of sickness, how we go down into the pit of death and feel the waters of annihilation close above our heads and wake thinking to find ourselves in the presence of the angels and the harpers when we have a tooth out and come to the surface in the dentist’s arm-chair and confuse his ‘Rinse the mouth-rinse the mouth’ with the greeting of the Deity stooping from the floor of heaven to welcome us—when we think of this, as we are so frequently forced to think of it, it becomes strange indeed that illness has not taken its place with love and battle and jealousy among the prime themes of literature.

Why don’t we have a literature of illness? Woolf gives a couple of good reasons. One is that literature’s truck is with the mind, not the body; it attempts to ignore the needs and the interventions of the physical plane. Even more crucially, the language to describe illness is severely impoverished: “Let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.” Unless it is compared to, say, love, physical pain is simply too difficult to convey. Pain can throb, ache, stab, sear, crunch, shoot, press in or push out—but these mere words do not do it justice much of the time, alone or in combination. As Elaine Scarry wrote in her 1985 study, The Body in Pain, “Physical pain—to invoke what is at this moment its single most familiar attribute—is language-destroying.”

Dillon’s lack of empathy rears a particularly ugly head in his chapters on women. Alice James is a good example. She writes upon learning she has cancer, “Ever since I have been ill, I have longed and long for some palpable disease, no matter how conventionally dreadful a label it might have, but I was always driven back to stagger alone under the monstrous mass of subjective sensations, which that sympathetic being ‘the medical man’ had no higher inspiration than to assure me I was personally responsible for, washing his hands of me with a graceful complacency under my very nose.” Dillon responds that James just liked the drama and the attention illness gave her. She is the classic invalid-as-career-woman. “[James’s] very self-possession seems a kind of pathology; it insulated her against the physically and emotionally unsettling expression of her real terror, and her real loneliness;” she was “just ill enough not to have to face the creative and emotional void at the heart of her short life.” Besides marriage, however, which all of Dillon’s female subjects forsook—or willfully avoided—what option is Alice James avoiding through her illness, or, as Dillon would argue, her hypochondriasis? Even the women who are working at something, like Brontë and Nightingale, are pathologized for their sickness in Dillon’s telling. He conflates their desire to be alone with hypochondria, when it was also the only way for them to have any control over their destinies. Virginia Woolf knew this very well, from books and from experience.

About the literature of illness, Woolf was right and wrong: No literature of illness has come along to compare to the literature of love, or even of work. The condition of the body is too complex for fiction. Death is always welcome as a plot point; it makes a tidy metaphor about loss, and forces pathos if not real grief and melancholy. But illness drags a story down: no great novels will be written about cancer, or Alzheimer’s, or, heaven forbid, diseases less grandiose but recurring, like arthritis or asthma. There is a sentimental literature about dying—Love Story, Tuesdays With Morrie, anything by Nicholas Sparks—but not a serious one.

Yet there is a secret literature of illness contained beneath the umbrella of one of the most popular genres around, the memoir. From Prozac Nation (depression) to Hurry Down Sunshine (bipolar illness) to The Year of the Gun (drug addiction), to name a precious few, mental illness is the solid frontrunner in the race for most popular complaint amongst the memoirists. Sure, there are books about concrete maladies: surviving cancer (Elizabeth Edwards), living with (or dying from) AIDS (Paul Monette), overcoming the hardships of abuse and poverty (Bastard out of Carolina, The Liar’s Club, Running with Scissors). Even in these books, mental illness plays a starring role, and it should, as we have enlarged the category to include behaviors that had long been either not talked about or not acknowledged as damaging. Yet has this equating of insanity and creativity made everything and everybody crazy, hypochondriacs in some self-conscious sense?

Dillon writes that the figure of the hypochondriac is often a fool, mocked, that the hypochondriac has “in common with the clown (for the hypochondriac is also a figure of fun) the tendency to repeat the same behavior, to make the same mistakes, in the face of all indications that one ought to desist.” The funniest of Dillon’s case studies is the final one, of Warhol, though its humor is derived more from irony (a defense, as Phillips reminds us) than raucousness. Warhol believed in the notion that perfect health is possible, in the notion of the “good body,” though his was a bad body, plagued by skin problems, thinning hair, lack of muscle tone, and, later, ugly scars from being shot. Still, Warhol was obsessed with beauty, with the possibility of perfecting physical appearance. He had the attitude that has made plastic surgery, the weight-loss industry, vitamins and gyms mainstays of contemporary life. Yet Dillon’s examination of Warhol is superficial: he gets the obsession with beauty right, obvious from the pretty boys who populated Warhol’s films and Factory and the female icons he painted over and over (Jackie, Marilyn, et al.). He tracks the fear of illness to a bout of St. Vitus Dance in Warhol’s childhood. It developed into a terror of death so profound he would say the departed had “gone to Bloomingdale’s.” But Dillon misses how clever Warhol’s hypochondria was, how deep his need to disavail himself of having a body, how he longed to break—or escape—physical being entirely.

Wayne Koestenbaum wrote, in his biography Andy Warhol, that “like the rest of us, [Warhol] advanced chronologically from birth to death; meanwhile, through pictures, he schemed to kill, tease, and rearrange time.” What loftier goal could the hypochondriac have than to “rearrange time,” thereby escaping aging and its ravages on the body? Koestenbaum also points out that Andy “liked to entrust others with the task of embodying Andy,” as in the time he sent someone else to sign his books at a bookstore, or in his well-known practice of having assistants make and sign his artwork. Where Dillon posits the money shot of Warhol’s hypochondriasis as the moment his wig was pulled off in public—a crisis of exposure—disembodiment was Warhol’s real goal. Dillon rightly repeats Warhol’s quip that it would be the “best American invention” to disappear, but he does not push that concept far enough. Koestenbaum connects this disappearing wish with Warhol’s surrounding himself with beauties, “as if they exist solely to frame and escort him. Warhol sought a contiguity, the state of standing next to: being next to a beauty, he could body swap.” It’s the hypochondriac’s koan: If he was beautiful, he would have no body to worry about; and without worry, Warhol’s body would disappear.

Yet worry, as Phillips writes (and Warhol certainly understood), also has an ironic side: “Worrying implies a future, a way of looking forward to things.” In order to worry properly, the hypochondriac must have his list of ailments on a repeating loop. Performed in this way, worry is “an ironic form of hope.” Warhol’s obsession with beauty makes him the exception. The hypochondriac usually fantasizes the worst, for the ultimate worry is death, and as long as the hypochondriac has that to worry about, there is an endless future of hypochondriasis to look forward to: something to live for. Death is not only the end of hope, it is the end of worry—the last thing a hypochondriac wants, and the only cure for what ails him.

Lisa Levy is a writer in Brooklyn, New York. Her book on modernism and biography, We Are All Modern, is forthcoming from FSG.

Mentioned in this review:

The Hypochondriacs

Illness as Metaphor

On Being Ill

The Body in Pain

Andy Warhol