Levi Asher is a writer and website developer. His blog Literary Kicks has been online since 1994.

Levi Asher is a writer and website developer. His blog Literary Kicks has been online since 1994.

Psychology is often concerned with origins, but the origin of modern psychology itself is murky. The field was born not from a great idea but from the lack of one. Philosophers had always studied the mind while scientists studied the physical universe, but the scientific revolution that followed the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species in 1859 seemed to call for a newly rigorous, evidence-based approach to the mysteries of the human mind. The word psychology already existed by then (in its Greek, Latin, French, German, Russian, and English equivalents), but it took a few brave souls to step forward and try to define an actual discipline worthy of the name.

In the U.S., William James was the first brave soul. In 1875, as a 33-year-old teacher of anatomy and physiology at Harvard, filled with broad and exciting ideas but mostly unknown to the world, James sent a letter to Harvard president Charles W. Eliot proposing a new course in psychology. Eliot approved the idea and James began teaching it, the first psychology course anywhere in the world, in 1876. He also began writing a textbook, The Principles of Psychology, which also would have been the world’s first if James had finished it quickly—but he did the opposite, working on it until 1890, by which time many other textbooks had been produced.

Not long after Principles was published, James began to reach a larger audience with his speeches and writings on philosophy, religion, and the nature of truth. And the field of psychology found its own Darwin—an electrifying presence with a revolutionary theory to prove—in Sigmund Freud, whose Interpretation of Dreams was published in 1900.

Freud and James met once, in 1909, at a gathering of psychologists at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. Several other soon-to-be-notable psychologists, including Carl Jung, Alfred Adler, and Ernest Jones had arrived with Freud. (Some, notably Jung, would later break with him, but at the time they formed his loyal entourage). Freud was clearly the star attraction at the conference, and it was to hear him speak that James, by this time an elderly eminence, 14 years older than Freud and in failing health, made the short trip to Worcester from Boston.

According to all accounts, Freud and James were eager to meet each other. The two men ended their brief encounter by strolling alone together to a train station, and a dramatic scene unfolded: James, suffering from heart problems, suddenly felt an attack of angina pectoris coming on, and asked Freud to walk ahead alone so he could gather himself. This appears to have ended their chance for a deeper conversation, and later accounts of the meeting by both men hint at an undefined tension underlying the friendly meeting.

James and Freud shared a fascination with the phenomenon of human consciousness. They both believed entirely in the essential, irreducible willfulness of human nature. It was James’ greatest discovery that our needs, desires, and hopes are the cornerstones of our belief systems. It was Freud’s greatest discovery that our needs, desires, and hopes have a mind of their own—the unconscious mind—and, in this capacity, influence everything we do. On the biggest questions of life, meaning, and existence, Jamesian philosophy and Freudian psychology can be harmonious.

Yet the two could be described as ideological opposites as well. James had great intellectual passion for religion, and Freud was a passionate atheist who wrote a book about religion called The Future of an Illusion. James was also decidedly a pluralist, whereas Freudian psychology located sexuality as the singular emotional core (and core trauma) of human existence. A broad, anti-dogmatic thinker like James could never fall for a belief system based on a single cause, a single anything. Life, James believed, was too rich for that.

One can only wonder at the private bemusement with which James might have greeted the outrageously controversial Freud in 1909. In a private letter, he gently mocked Freud’s theories about dreams as the key to psychological revelation. But his own Principles of Psychology inexplicably contains only a simple half page about the phenomenon of dreaming (though it contains painfully long sections about, for instance, the perception of space and the phenomenon of optical illusions).

James knew that Freud’s energetic research had value, whatever its flaws or overreaching. It also seems likely that Freud’s more brazen statements would have pleased James for their audacity. Like Freud, James was no prude, and he didn’t mind shocking the academy every now and then.

Finally, as a father of pragmatism, James admired the fact that Freud’s reputation rested on actual clinical success. Psychoanalysis was the Freudian “pragma,” and it was known to actually cure patients in the field. By generously embracing and lending his credibility to the upstart Freud, James was acting as a pluralist, a pragmatist, and, above all, a man with love to spare for his embattled fellow thinkers.

As for explaining the awkwardness between the aging American genius and his younger European rival, a Freudian interpretation might come in handy.

From “The Sick Soul” by William James, part of The Varieties of Religious Experience:

From “The Sick Soul” by William James, part of The Varieties of Religious Experience: Next week, Harvard University Press will publish

Next week, Harvard University Press will publish  Levi Asher is a writer and website developer. His blog

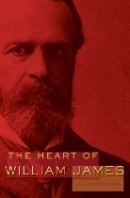

Levi Asher is a writer and website developer. His blog  As part of the William James festivities around here, I’m giving away a copy of what is probably my favorite book, The Varieties of Religious Experience. Based on a series of lectures that James delivered at the University of Edinburgh in 1901 and 1902, Varieties combines fascinating firsthand accounts of people’s experiences with James’ brilliant and timeless insights about the psychology, needs, frailty, and resilience of human beings. James was famously kind to (and drawn to) religion and the supernatural for someone as scientifically inclined as he was, but he still felt the need to acknowledge that some of the most devout might find his techniques off-putting:

As part of the William James festivities around here, I’m giving away a copy of what is probably my favorite book, The Varieties of Religious Experience. Based on a series of lectures that James delivered at the University of Edinburgh in 1901 and 1902, Varieties combines fascinating firsthand accounts of people’s experiences with James’ brilliant and timeless insights about the psychology, needs, frailty, and resilience of human beings. James was famously kind to (and drawn to) religion and the supernatural for someone as scientifically inclined as he was, but he still felt the need to acknowledge that some of the most devout might find his techniques off-putting: Three incidents serve to illustrate the contentious nature of Henry James’ relationship with his older brother William.

Three incidents serve to illustrate the contentious nature of Henry James’ relationship with his older brother William. On August 26, 1910, William James died at the age of 68. To mark the centenary of his death, this week on The Second Pass will be devoted to James.

On August 26, 1910, William James died at the age of 68. To mark the centenary of his death, this week on The Second Pass will be devoted to James. Preeminent literary critic, essayist, and academic Frank Kermode has died at 90. In

Preeminent literary critic, essayist, and academic Frank Kermode has died at 90. In  At The Millions, Craig Fehrman presents

At The Millions, Craig Fehrman presents  This Missouri Review

This Missouri Review  David L. Ulin

David L. Ulin  When the Caustic Cover Critic, who has a great eye for the bizarre and grotesque in book design (as well as the sublime), titles a post

When the Caustic Cover Critic, who has a great eye for the bizarre and grotesque in book design (as well as the sublime), titles a post  Tom Nissley

Tom Nissley  Rosecrans Baldwin’s debut novel,

Rosecrans Baldwin’s debut novel,  Caitlin Roper

Caitlin Roper  Francine Prose

Francine Prose  From

From  Jimmy Chen at HTML Giant has been tracking trends in the book cover industry: covers with

Jimmy Chen at HTML Giant has been tracking trends in the book cover industry: covers with  Juliet Waters has a great idea. Like many of us, she’s tired (to the point of collapse) of Jane Austen vs.

Juliet Waters has a great idea. Like many of us, she’s tired (to the point of collapse) of Jane Austen vs.  There are things I keep promising to do, two of which jump out at me: Review Reality Hunger (which will happen, and soon), and read Robert Walser. The latter might have to wait a little while longer, but that didn’t keep my from enjoying

There are things I keep promising to do, two of which jump out at me: Review Reality Hunger (which will happen, and soon), and read Robert Walser. The latter might have to wait a little while longer, but that didn’t keep my from enjoying  Welcome to the first book giveaway on The Second Pass. It’s a tradition on other sites, and I hope I can do more of it in the future. This initial offering is the Penguin Classics edition of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. A lovely book, it can be yours for nothing at all. Just send an e-mail to john[at]thesecondpass[dot]com, with Pynchon in the subject line. If you’d like to add a brief note, telling me how much you like the site, or a way you think it could be improved, or who you think will win the National League’s central division this year, I would love that. No mailing address necessary — I’ll contact the winner for that. Winner will be determined by random drawing. I’ll accept entries until 11:59 p.m. on Sunday, August 8th.

Welcome to the first book giveaway on The Second Pass. It’s a tradition on other sites, and I hope I can do more of it in the future. This initial offering is the Penguin Classics edition of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. A lovely book, it can be yours for nothing at all. Just send an e-mail to john[at]thesecondpass[dot]com, with Pynchon in the subject line. If you’d like to add a brief note, telling me how much you like the site, or a way you think it could be improved, or who you think will win the National League’s central division this year, I would love that. No mailing address necessary — I’ll contact the winner for that. Winner will be determined by random drawing. I’ll accept entries until 11:59 p.m. on Sunday, August 8th. Last Friday marked the 75th anniversary of Penguin Books. Now a worldwide publisher of diverse titles in diverse formats, the press started in Britain as the brainchild of Allen Lane. As Phil Baines writes in the beautiful

Last Friday marked the 75th anniversary of Penguin Books. Now a worldwide publisher of diverse titles in diverse formats, the press started in Britain as the brainchild of Allen Lane. As Phil Baines writes in the beautiful  Diane Johnson

Diane Johnson