Rachel Cooke writes smartly, at length, about Philip Larkin’s posthumous reputation. (“Beyond noting that his private utterances were in marked contrast to his public behaviour, which was ever polite, Larkin’s racism is uncomfortable and indefensible, even when you put it in the context of his times. The charges of misogyny, though, are about to start looking a whole lot more flimsy.”) . . . The Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest asks participants to write the worst opening sentence to an imaginary novel. The 2010 winner has been announced. . . . David Grossman’s new novel

Rachel Cooke writes smartly, at length, about Philip Larkin’s posthumous reputation. (“Beyond noting that his private utterances were in marked contrast to his public behaviour, which was ever polite, Larkin’s racism is uncomfortable and indefensible, even when you put it in the context of his times. The charges of misogyny, though, are about to start looking a whole lot more flimsy.”) . . . The Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest asks participants to write the worst opening sentence to an imaginary novel. The 2010 winner has been announced. . . . David Grossman’s new novel is one of the fall releases I’m most looking forward to reading. Scott Esposito points out that it comes with a hilariously overwrought blurb from Nicole Krauss. . . . Michael Popek finds a Yankees-Red Sox ticket stub from 1955 in an old paperback. . . . How in the world did Harper Lee become a bestseller without being on Twitter? . . . Lee recently agreed to meet a reporter, but they only fed ducks together. The condition was: No talk of To Kill a Mockingbird. . . . Today is what June should feel like, thank heavens, but the week’s earlier mugginess got Lisa Peet thinking of books about New York’s waterways.

Archives, June, 2010

Wednesday, June 30th, 2010

In the Ether

Tuesday, June 29th, 2010

Icebreaker

The opening sentence of The Boarding-House by William Trevor:

“I am dying,” said William Wagner Bird on the night of August 13th, turning his face towards the wall for privacy, sighing at the little bunches of forget-me-not on the wallpaper.

Tuesday, June 29th, 2010

Humility Lessons

In last weekend’s New York Times Magazine, Wyatt Mason profiled David Mitchell, whose latest novel is reviewed in the Circulating section today. The first paragraph of the profile is below. Mason goes on to say that Mitchell could understandably be “accused of unbridled self-effacement,” but by the end of the piece, the scope and confidence of his ambition is clear.

In last weekend’s New York Times Magazine, Wyatt Mason profiled David Mitchell, whose latest novel is reviewed in the Circulating section today. The first paragraph of the profile is below. Mason goes on to say that Mitchell could understandably be “accused of unbridled self-effacement,” but by the end of the piece, the scope and confidence of his ambition is clear.

(Photo of Mitchell by Koos Breukel for the New York Times)

As the Eyjafjallajokull Volcano was spewing plumes of ash into European airspace in April, shuttering airports and stranding millions, the British novelist David Mitchell, a tall, gracious, high-spirited man of 41, was marching me across a long, flat tidal beach near his home in Ireland’s West Cork. Along the way, he told me a story about the perils of humility. “I had a short and rather valuable lesson,” Mitchell said after a morning on the beach, “one of these warnings that the universe gives you on a platter sometimes. I’d done an event in New Zealand at a very large auditorium, hundreds of people, and I was kind of pleased with it; it had gone well. A woman came up to me afterwards, a medievalist at the university there, and she said, ‘Have you heard of the humility topos?’ I said no. She explained that, in the medieval era, humility was seen as a great virtue. The humility topos was used for these abbots — you can think of a good one in Eco’s ‘Name of the Rose’ — who were actually monsters of arrogance, but were always banging on about how humble they were — ‘Just like our lord Jesus Christ. We serve him in humility’ — when they were the least humble people you can find in history. Some even became pope. And the woman looked at me and said, ‘Watch out for the humility topos.’ And then sort of disappeared in a puff of smoke.”

Monday, June 28th, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Ron Charles reviews The Quickening Maze by Adam Foulds, which was shortlisted for last year’s Booker Prize. It’s set at a British mental asylum around 1840, and follows several characters, including the poet John Clare. Charles: “These are difficult characters because they’re so easy to play for laughs or sentimentality, but Foulds conveys the profound loneliness of mental illness, the anxiety of being at least partially aware of one’s own peculiarity.” . . . Wyatt Mason addresses a new book based on interviews with David Foster Wallace (quoted in the post below this one), and moves on to a larger argument about Wallace, editing, modernism, and realism. . . . Second Pass contributor Alexander Nazaryan reviews a “uniformly excellent book” about the British Empire’s doomed efforts to conquer the Arctic. . . . Terry McDermott’s new book puts readers in the lab of a radical neuroscientist researching memory. Sara Lippincott admires the result. . . . David Levering Lewis calls Bruce Watson’s Freedom Summer, “a well-researched, vivid retelling of the 1964 civil rights crusade to put Mississippi’s 200,000 disfranchised blacks on the voting rolls.” . . . Sheila McNulty says: “When John Hofmeister wrote [Why We Hate the Oil Companies], the former president of Royal Dutch Shell’s US business could have had no idea it would be published amid an oil spill gushing into the Gulf of Mexico. The title he chose could not have been more apt.”

Ron Charles reviews The Quickening Maze by Adam Foulds, which was shortlisted for last year’s Booker Prize. It’s set at a British mental asylum around 1840, and follows several characters, including the poet John Clare. Charles: “These are difficult characters because they’re so easy to play for laughs or sentimentality, but Foulds conveys the profound loneliness of mental illness, the anxiety of being at least partially aware of one’s own peculiarity.” . . . Wyatt Mason addresses a new book based on interviews with David Foster Wallace (quoted in the post below this one), and moves on to a larger argument about Wallace, editing, modernism, and realism. . . . Second Pass contributor Alexander Nazaryan reviews a “uniformly excellent book” about the British Empire’s doomed efforts to conquer the Arctic. . . . Terry McDermott’s new book puts readers in the lab of a radical neuroscientist researching memory. Sara Lippincott admires the result. . . . David Levering Lewis calls Bruce Watson’s Freedom Summer, “a well-researched, vivid retelling of the 1964 civil rights crusade to put Mississippi’s 200,000 disfranchised blacks on the voting rolls.” . . . Sheila McNulty says: “When John Hofmeister wrote [Why We Hate the Oil Companies], the former president of Royal Dutch Shell’s US business could have had no idea it would be published amid an oil spill gushing into the Gulf of Mexico. The title he chose could not have been more apt.”

Monday, June 28th, 2010

“We absolutely have to give our power away.”

Ryan Chapman shares an excerpt from a new book about David Foster Wallace, in which Wallace discusses the future of the Internet. (This was in 1996.) And I think his sentiments are germane, whether you agree with them or not, to my post from last week about the slush pile and the future of publishing:

Because this idea that the Internet’s gonna become incredibly democratic? I mean, if you’ve spent any time on the Web, you know that it’s not gonna be, because that’s completely overwhelming. There are four trillion bits coming at you, 99 percent of them are shit, and it’s too much work to do triage to decide. . . .

If you go back to Hobbes, and why we ended up begging, why people in a state of nature end up begging for a ruler who has the power of life and death over them? We absolutely have to give our power away. The Internet is going to be exactly the same way. Unless there are walls and sites and gatekeepers that say, “All right, you want fairly good fiction on the Web? Let us pick it for you.” Because it’s gonna take you four days to find something any good, through all the shit that’s gonna come, right?

We’re going to beg for it. We are literally gonna pay for it. But once we do that, then all these democratic hoo-hah dreams of the Internet will of course have gone down the pipes. And we’re back again to three or four Hollywood studios, or four or five publishing houses, being the . . . right? And all of us who grouse, all the anarchists who grouse about power being localized in these media elites, are gonna realize that the actual system dictates that. The same way—I’m absolutely convinced—that the despot in Hobbes is a logical extension of what the State of Nature is.

Monday, June 28th, 2010

The Cherry & the Pit

A continuing series that highlights books recently acquired by publishing houses for future release. Each post features a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

The Cherry:

Bill Goldstein’s The World Broke in Two, a literary history of the year 1922 in the intertwined lives of Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence, E.M. Forster and T.S. Eliot.

The Pit:

Clea Simon’s Dogs Don’t Lie, first in a new “pet noir” series featuring a bad-girl animal psychic and her sidekick, a crotchety tabby.

Monday, June 28th, 2010

Sergei at the Track

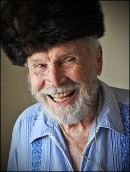

Over the weekend, the Washington Post ran a profile of 87-year-old Sergei Tolstoy, great-grandson of you-know-who. He’s trying to sell a memoir about time he claims he spent as a spy for the U.S.

Over the weekend, the Washington Post ran a profile of 87-year-old Sergei Tolstoy, great-grandson of you-know-who. He’s trying to sell a memoir about time he claims he spent as a spy for the U.S.

As a racing fan, this was my favorite part of the piece:

Not so long ago, he reveled in the luxuries his last name and aristocratic status afforded him. He dined with dignitaries in Washington’s finest restaurants. His taste was so exquisite and his style so extravagant that a cigar company named a Cohiba for him.

Now he says his only income is a $213 monthly check from Social Security. His monthly rent at St. Mary’s Court, where he has resided for 19 years, is $64. After utilities, what’s left he spends at the nearby convenience store on magazines and licorice.

“I’m living like a bohemian,” he jokes with a rascally grin. “I beg, borrow and steal.”

According to people who have known him for more than 30 years, Tolstoy’s money is gone, vanished, lost at the betting windows of the Laurel, Bowie, Timonium and Pimlico racetracks he used to roam six days a week.

“I made my bread and butter at the track,” he says. “Many rich ladies wanted to marry me and become Countess Tolstoy. It is too late now, but I could have been a millionaire.”

(Photo by Bill O’Leary for the Washington Post)

Friday, June 25th, 2010

The Slushy Future

I’m a few days late on this, but Salon’s Laura Miller wrote a terrific piece about the possible future of book publishing. It’s the future being touted by many as the Happy Happy Land of No Gatekeepers, where writers and readers (but mostly writers; we’ll get to that) bypass the big, mean traditional publishers who keep so many great books from seeing the light of day. Miller’s column boils down to a question: “Is the public prepared to meet the slush pile?” Her answer could have been a simple “no,” but that would be much less smart, entertaining, and right than the longer answer she gives. (For any lucky souls who may not know, “slush pile” is slang for the teetering stacks of unsolicited material received by magazines and book publishers.)

I feel particularly motivated (and qualified) to write about this because I was one of a few people who handled the slush at Harper’s Magazine during a four-month internship about a decade ago, and then I read plenty of unsolicited material during my ensuing time in the editorial department at HarperCollins.

Miller writes:

You’ve either experienced slush or you haven’t, and the difference is not trivial. People who have never had the job of reading through the heaps of unsolicited manuscripts sent to anyone even remotely connected with publishing typically have no inkling of two awful facts: 1) just how much slush is out there, and 2) how really, really, really, really terrible the vast majority of it is.

Yes, indeed. The slush pile’s main strength is as an unintentional source of hilarity. At Harper’s, a good friend and I were particularly thrilled by regular dispatches from a reader in New Jersey, long essays that included crude, hand-drawn illustrations and many sentences like these: “The sun is made of hydrogen. THAT IS A FACT!!”

Miller writes:

Everybody acknowledges that there have to be a few gems out in the slush pile — one manuscript in 10,000, say — buried under all the dreck. The problem lies in finding it. A diamond encased in a mountain of solid granite may be truly valuable, but at a certain point the cost of extracting it exceeds the value of the jewel.

The truth is, diamonds have their chance. There is self-publishing, after all, and if someone’s work is good or popular enough, that route often leads to a bigger distribution deal with . . . a traditional publisher. The other, hard truth is that some diamonds go unnoticed. Such is life. Does this mean that we have to read manuscripts (or self-published books) by everyone on the planet for fear of missing a possible gem? It’s hard to imagine anyone so obsessed with not letting a single diamond go unnoticed that they devote their life to staring at granite.

What Miller implies is something I wholeheartedly believe, which is that one could just as easily make the argument that there aren’t enough gatekeepers. There are days when I think there are more literary agents in New York than hot dog vendors. These agents are constantly competing to find new talent, scouring obscure journals, and the fact is that they find too much. Forget slush piles. Reading material represented by agents (which was a light-years advance in quality over reading slush), I would still be disappointed/unmoved/unimpressed by, what, 85% of it? Some of that percentage is simply accounted for by personal taste, of course, but not nearly all of it.

A reader named Jeff Maehre left this comment on Miller’s essay:

To say that one manuscript out of ten thousand in your “slush pile” is a gem is to be grossly out of touch with realities of what’s going on in publishing now.

Authors who win Pushcart Prizes are unable to sell their collections of short stories. Authors of fifteen published books find themselves unable to sell their manuscripts and if they do publish them, do so as the winners of university-sponsored contests. These books may not meet your definition of “gem,” but they don’t deserve to be called “dreck” any more than the average offering from Putnam or FSG.

You write as someone taking a wild guess at what the publishing world is like.

Unfortunately, it is actually the case that authors of intricately-crafted, compelling works find themselves in slush piles on a widespread basis. And I’m sure any editor of any publishing house or any literary nationally-distributed literary journal will tell you the same.

It sounds like Jeff has never read a slush pile. But even if he has, it’s fair to say “dreck” is a strong word. It’s equally fair to point out, though, that having a story selected for a Pushcart Prize does not mean your entire collection of short stories is worthy of publication. I’m pretty sure that most editors in publishing would disagree with Jeff.

And while we’re at it, let’s not forget that the publishing world hardly consists of only massive conglomerate publishers, even though they’re the easiest targets. I’m not defending large publishers here, per se (though if you can find me the self-published books that can compete with the lists at Knopf, FSG, etc., I’ll buy you a very nice dinner). Large publishers operate more and more by committee, and as one of my favorite proverbs has it, a camel is a horse made by committee. There are lots and lots of camels out there. Dreck is given imprimatur all the time. Good things are ignored by big publishers all the time.

But if I have it right, the argument is that too few books are published, not too many, and it takes a blinkered view of things to think of publishing as just the conglomerates, even with their increasingly consolidated powers. There are many small publishers devoted to smaller, less obviously commercial work. These publishers, no matter how independent, still represent an experience distinct from self-publishing.

Another commenter, “AchillesisCrying,” writes:

This whole idea of the publishing industry being just a bunch of well-meaning literature lovers puttering around their tiny little cluttered NY offices is nonsense. Publishing is controlled by large multi-national conglomerates. The industry is driven by marketing. When the self-publishing revolution topples it, will there be bad books? Sure. (There are plenty of bad books now, so I don’t see why we have to nod obediently when the publishing industry tells us that we don’t know what we’re talking about). Something else better will rise in its place.

Besides, pretty much every other art form has embraced DIY. Take music for example, you can write an album, play every instrument and sing, record and distribute and it yourself and nobody gives a shit about that, as long as it’s good. Same for film and visual arts. Only in books is DIY a stigma. And I understand why: it is a direct threat to their business. And that is all.

Well, sure, I can tell you the industry is not teeming with “well-meaning literature lovers,” but this screed answers itself. “There are plenty of bad books now,” saith Achilles. Yes, and these books are published by a wide (even dizzying) array of outlets, including, already, the authors themselves. So how we get from this to “something better” by lowering the barriers to publication isn’t immediately clear to me. DIY is a stigma, broadly speaking, because DIY can mean anything, and most of anything is bad. It’s that simple. Publishers are not frightened by the latent powers of the slush pile, believe me.

If anything, most bitterness about the publishing industry is driven by frustrated writers, not frustrated readers, who are already absolutely buried in options. As Miller says:

People who claim that there are readers slavering to get their hands on previously rejected books always seem to have a previously rejected book to peddle; maybe they’re correct in their assessment, but they’re far from impartial. Readers themselves rarely complain that there isn’t enough of a selection on Amazon or in their local superstore; they’re more likely to ask for help in narrowing down their choices.

Friday, June 25th, 2010

The Longest Reads

Abe Books rounds up 15 of the longest novels of all time, and provides pithy, Twitter-length summaries for them. For instance, Remembrance Rock

Abe Books rounds up 15 of the longest novels of all time, and provides pithy, Twitter-length summaries for them. For instance, Remembrance Rock by Carl Sandburg: “Three centuries of the American dream. From the Pilgrims to World War II. Hail to America. High fives.” And War and Peace

: “Napoleon & Co invade Russia but that’s the least of the problems for five posh Russian families. Love and cannonballs. Much war, little peace.”

I remember one of these books, The Far Pavilions by M. M. Kaye, sitting on my parents’ book shelf when I was very young. Then one day, it started appearing on the coffee table. Dad was actually reading it! And I remember thinking: It would take years to read something like that. He managed to finish in a couple of weeks, and my notion of what was possible changed.

I read all of Infinite Jest, including every footnote at the appropriate time, but Atlas Shrugged is probably the longest novel I’ve ever read. And boy, did it feel like it.

Wednesday, June 23rd, 2010

“Her soul had locked itself onto his senses.”

Yipes. Carolyn Kellogg at the L. A. Times points to the paper’s review of Glenn Beck’s new novel, The Overton Window, which includes this excerpt from the book:

Yipes. Carolyn Kellogg at the L. A. Times points to the paper’s review of Glenn Beck’s new novel, The Overton Window, which includes this excerpt from the book:

Something about this woman defied a traditional chick-at-a-glance inventory. Without a doubt all the goodies were in all the right places, but no mere scale of one to 10 was going to do the job this time. It was an entirely new experience for him. Though he’d been in her presence for less than a minute, her soul had locked itself onto his senses, far more than her substance had.

That makes Ayn Rand read like Walt Whitman. The promotional copy calls the novel “a ripped-from-the-headlines thriller,” though I think it only refers to the headlines on the crazy newspapers that spin around in Glenn Beck’s head.

One reviewer of the book on Amazon wrote, “I laughed, I cried, I sold it at Half Price Books in Houston and got $3.50 for it.” But my favorite comment about the novel came from novelist Alexander Chee. Beck has been saying that he calls his work “faction” — fiction based on fact. Chee wrote: “Dear Glenn Beck: ‘factional’ is already a word that doesn’t mean ‘fact-based fiction,’ but ‘related to a self-seeking contentious minority.’”

Wednesday, June 23rd, 2010

Will Write for Food (and Stars)

Writers at The Morning News recently interviewed some of their own children (most of them 7 or younger) about their summer reading. The results are charming, as you might expect. They also show that these children have an acute understanding of the economic realities of being a writer, as evidenced by their answers to one particular question:

How much do you think the writer got paid?

Ten dollars.How much do you think the writer got paid to write the book?

Hundreds. About 1,000? No, 10 pounds.How much do you think the writer got paid?

Seven cents.How much do you think the writer got paid to write the book?

$50.How much do you think the author got paid?

Twenty dollars and 20 stars.

Tuesday, June 22nd, 2010

More Attention for the Under-40 Set

Britain’s Telegraph responds to The New Yorker’s recent list of 20 notable writers younger than 40 with a list of its own. I hadn’t heard of eight writers on the list, so it’s an education, at least. One of those writers, Joanna Kavenna, has evidently been described as “Dostoevsky meets Bridget Jones,” just in case you needed your head to explode.

I was dreading to see someone born in 1985 or 1986, which would have given an extra kick to my thoughts of mortality. But only Evie Wyld had the temerity to be born in the eighties, and 1980 at that.

The Millions also recently got in on the game, unleashing a “20 More Under 40″ list. I’ve heard of all 20 on that list, but have only read a handful. Glad to see Tom Bissell and Samantha Hunt on there.

Monday, June 21st, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

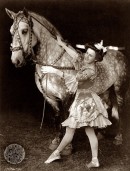

Jed Perl writes about the deep roots of the circus’ appeal, and says that a new collection of Frederick W. Glasier’s circus photos from the first quarter of the 20th century is “one of the most beautiful art books of recent years.” . . . John Self enjoys a “witty, digressive” book about British roads. (“On Roads: A Hidden History is catnip for anyone, like me, who regrets that the Black Box Recorder song ‘The English Motorway System’ was actually a metaphor for a stagnant relationship and not just about the roads.”) . . . Ben Greenman’s latest collection takes the form of fictional letters between characters. Steve Almond says the stories are “as assured and persuasive” as any he’s read in a long time: “Greenman has the ear of a mimic, the mind of a philosopher and the timing of a stand-up comic.” . . . George Packer reviews Peter Beinart’s new book, in which Beinart looks back at a century of American history and regrets his own strong support for the Iraq War. (“The Icarus Syndrome finds the ground littered with Peter Beinarts, lying amid the remnants of large ideas and unearned confidence.”) . . . Roy Blount, Jr., takes issue with a book that celebrates the global triumph of the English language.

Jed Perl writes about the deep roots of the circus’ appeal, and says that a new collection of Frederick W. Glasier’s circus photos from the first quarter of the 20th century is “one of the most beautiful art books of recent years.” . . . John Self enjoys a “witty, digressive” book about British roads. (“On Roads: A Hidden History is catnip for anyone, like me, who regrets that the Black Box Recorder song ‘The English Motorway System’ was actually a metaphor for a stagnant relationship and not just about the roads.”) . . . Ben Greenman’s latest collection takes the form of fictional letters between characters. Steve Almond says the stories are “as assured and persuasive” as any he’s read in a long time: “Greenman has the ear of a mimic, the mind of a philosopher and the timing of a stand-up comic.” . . . George Packer reviews Peter Beinart’s new book, in which Beinart looks back at a century of American history and regrets his own strong support for the Iraq War. (“The Icarus Syndrome finds the ground littered with Peter Beinarts, lying amid the remnants of large ideas and unearned confidence.”) . . . Roy Blount, Jr., takes issue with a book that celebrates the global triumph of the English language.

Monday, June 21st, 2010

More Feed

When I mentioned the Feed archives last week, I was premature in naming two friends of mine that wrote for the site. Once I started digging deeper into the archives, I realized that many people I know deserved acknowledgment as contributors: Jason Zinoman, Deborah Shapiro, Lauren Sandler, Lisa Levy, Matt Weiland, and Aaron Retica, to name a few. While they were writing on the online frontier, I’m pretty sure I was watching SportsCenter somewhere outside Dallas.

If you haven’t yet, take some time to browse the site’s offerings on books. They include Alex Star on Philip Roth, Tom Wolfe, Jonathan Franzen, and the anxieties of the American novelist; Adam Kirsch on the children’s writing of Oscar Wilde; and Lisa Levy on the journals of Sylvia Plath.

Monday, June 21st, 2010

“We’re all cowardly and ironic animals.”

The Tottenville Review, a recently launched site devoted mostly to the work of debut authors, spoke to novelist Jeffrey Rotter. I enjoyed it, and not just because I share this sentiment of his: “I don’t believe lettuce belongs on a sandwich.” Along with some talk about his book, Rotter and interviewer Jason Porter go out of their way to keep things entertaining:

The Tottenville Review, a recently launched site devoted mostly to the work of debut authors, spoke to novelist Jeffrey Rotter. I enjoyed it, and not just because I share this sentiment of his: “I don’t believe lettuce belongs on a sandwich.” Along with some talk about his book, Rotter and interviewer Jason Porter go out of their way to keep things entertaining:

INTERVIEWER: On the topic of barnyards, do you eat animals? Would you eat animals in front of animals?

JEFFREY ROTTER: I do. I have. Animals have eaten animals in front of me. An animal has never, to my knowledge, eaten a human in front of me. Though my cat chomped on my arm recently and sent me to the hospital for two days with cellulitis. I am not averse to eating him, should the need arise. I don’t eat much meat anymore, and when I do I try to make it the good stuff, the “humane” kind. And I’ve ruled out octopus. I won’t eat anything that can open a jar, or shape-shift, or yank out my uvula with its tentacles.

Friday, June 18th, 2010

“Either we are blind, or we are mad.”

Nobel Prize-winning novelist José Saramago has died at age 87. In response, The Paris Review posts its 1998 Art of Fiction interview with Saramago. I enjoyed this image, in particular:

Nobel Prize-winning novelist José Saramago has died at age 87. In response, The Paris Review posts its 1998 Art of Fiction interview with Saramago. I enjoyed this image, in particular:

Interviewer: What about your characters? Do your characters ever surprise you?

Saramago: I don’t believe in the notion that some characters have lives of their own and the author follows after them. The author has to be careful not to force the character to do something that would go against the logic of that character’s personality, but the character does not have independence. The character is trapped in the author’s hand, in my hand, but he is trapped in a way he does not know he is trapped. The characters are on strings, but the strings are loose; the characters enjoy the illusion of freedom, of independence, but they cannot go where I do not want them to go. When that happens, the author must pull on the string and say to them, I am in charge here.

In response to a question about perhaps his best-known work, Blindness, he said:

I am a pessimist, but not so much so that I would shoot myself in the head. The cruelty to which you refer is the everyday cruelty that occurs in all parts of the world, not just in the novel. And we at this very moment are enveloped in an epidemic of white blindness. Blindness is a metaphor for the blindness of human reason. This is a blindness that permits us, without any conflict, to send a craft to Mars to examine rock formations on that planet while at the same time allowing millions of human beings to starve on this planet. Either we are blind, or we are mad.

Thursday, June 17th, 2010

Jurassic Park, Internet Edition

In 1995—which, on the Adjusted Technology Timeline, is roughly the equivalent of 1724—Stefanie Syman and Steven Johnson had the foresight to start Feed, an online magazine that foreshadowed Slate, Salon, and other online-only journalism and literature. Feed closed up shop in 2001, and for a long while, the archives—which featured writing by Geoff Dyer, Sam Lipsyte, Keith Gessen, and good friends of mine like Jon Fasman and James Ryerson—were unavailable. Now they’re back up.

In 1995—which, on the Adjusted Technology Timeline, is roughly the equivalent of 1724—Stefanie Syman and Steven Johnson had the foresight to start Feed, an online magazine that foreshadowed Slate, Salon, and other online-only journalism and literature. Feed closed up shop in 2001, and for a long while, the archives—which featured writing by Geoff Dyer, Sam Lipsyte, Keith Gessen, and good friends of mine like Jon Fasman and James Ryerson—were unavailable. Now they’re back up.

In the coming days, I’ll share some clips from the site’s writing about books, but for now, some excerpts from Lipsyte. In a new note about his memories of the site, he writes:

These were freewheeling days. The rule seemed to be that if you cared about a piece, and could make an argument for its cultural or political or technological importance, or else its downright hilarity, it belonged on FEED. This was editorial heaven. There weren’t even enough of us for feuds or office politics. Writing and editing the FEED dailies was my favorite gig. I look over the ones I wrote with real trembling. Do they hold up? Of course not, idiot! But a lot of the stuff by other people does, and surprisingly well.

Lipsyte’s six-part 1996 feature about being recruited for an infomercial, “Memoirs of an Infowhore,” holds up very well. It includes this great sentence, among others: “He looked like Brian De Palma, but with a sadness around the eyes that said, ‘I am not Brian De Palma.’ ” The story starts when Lipsyte and a friend were approached by a two-person camera crew in Central Park:

We have cameras on us all the time. But this camera was different. It beckoned me, all my efflorescence. This was an audition, I knew, not just for these adwomen, but for the Heavens, for the principles of joy I saw in practice all around me on this sweet and gleaming day.

I was wonderful: clear-eyed and benignly sardonic, self-assured, self-mocking. They asked me questions about my exercise habits, my feelings about fitness, my relationship to my body. “The” body I wanted to interject, but clearly they meant “my” body.

Well, my body sucks. I have always felt estranged from it. When I was a child watching Star Trek re-runs before dinner I did not want to be Kirk or Spock or even Uhura (although she was my first TV crush). I wanted to be one of those free-range brains floating around in a cave on some godforsaken asteroid.

During my audition in the park, of course, I touched on none of this. This was not America’s Most Therapeutic videos, after all. I tried my best to be the vaguely-hipster offbeat regular guy. You know the one, you’ve seen the sitcoms. I intuited my niche and crawled right inside.

“If you could have any movie star’s body, who’s would it be?” They asked.

“Jamie Lee Curtis,” I answered without hesitation.

The woman with the camera guffawed and gave me the thumbs up.

I was kicking ass!

Thursday, June 17th, 2010

Melville on the Beach

Lapham’s Quarterly has updated its web site to reflect the new issue, “Sports & Games.” One of the choice bits available online is Herman Melville writing about surfers in Tahiti in 1849. A piece:

Lapham’s Quarterly has updated its web site to reflect the new issue, “Sports & Games.” One of the choice bits available online is Herman Melville writing about surfers in Tahiti in 1849. A piece:

For this sport a surfboard is indispensable, some five feet in length, the width of a man’s body, convex on both sides, highly polished, and rounded at the ends. It is held in high estimation, invariably oiled after use, and hung up conspicuously in the dwelling of the owner.

Ranged on the beach, the bathers by hundreds dash in and, diving under the swells, make straight for the outer sea, pausing not till the comparatively smooth expanse beyond has been gained. Here, throwing themselves upon their boards, tranquilly they wait for a billow that suits. Snatching them up, it hurries them landward, volume and speed both increasing till it races along a watery wall like the smooth, awful verge of Niagara.

Wednesday, June 16th, 2010

In the Ether

Mary Gaitskill walks around a bookstore, filmed by the folks at Stacked Up. She’s very candid and charming. And she gets big points from me for lifting up a copy of DeLillo’s White Noise and saying: “Actually, I didn’t like it so much. I feel free to say that because it’s like shooting spitballs at a tank.” She also praises what she’s currently reading, “one of the best things I’ve read in the last decade.” [OK, a reader took issue with my teasing Gaitskill's pick rather than naming it: The book she loves is Agaat

Mary Gaitskill walks around a bookstore, filmed by the folks at Stacked Up. She’s very candid and charming. And she gets big points from me for lifting up a copy of DeLillo’s White Noise and saying: “Actually, I didn’t like it so much. I feel free to say that because it’s like shooting spitballs at a tank.” She also praises what she’s currently reading, “one of the best things I’ve read in the last decade.” [OK, a reader took issue with my teasing Gaitskill's pick rather than naming it: The book she loves is Agaat by Marlene van Niekerk.] . . . It’s always fun to check in with Odd Books. The latest: Mans, Minerals and Masters by Charles W. Littlefield. (“Drawing on the (uncredited) work of the quack Schuessler, Littlefield’s researches gave him the idea that mineral salts in the body could respond to mental transmissions. They would do so by forming images of mystical import, visible through the microscope, which could not merely stop bleedings but were actually the root of life.”) . . . Carolyn Kellogg shares a “partial list” of today’s Bloomsday celebrations across the country. Not included is the celebration I’ll likely be attending tonight. . . . An ambitious summer project is underway: At the Summer of Genji, the Quarterly Conversation and Open Letters have teamed up to read 90 pages of The Tale of Genji every week until the end of August. . . . Omnivoracious kicks off a week dedicated to Alasdair Gray and his new novel with an interview by Jeff VanderMeer. . . . Alan Bisbort shares a long list of preferred baseball reading. . . . As part of World Cup fever — an affliction to which I seem perfectly immune — Sara at the New York Review cites a soccer-based passage from Envy by Yuri Olesha, a short novel that will be praised in passing by a reviewer here sometime in the coming days. . . . D. G. Myers expresses the heartbreak of leaving a stunning personal library behind.

Tuesday, June 15th, 2010

Man v. Newt

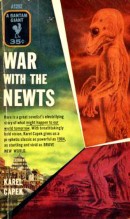

A year or more ago, I was browsing at the Barnes & Noble in Union Square (one of the best bookstores in New York for browsing), and I came across a novel called War with the Newts by Karel Čapek. And I bought it, because, in case you hadn’t noticed, it’s called War with the Newts. Like many books I buy, I haven’t gotten around to reading it yet, but John Self’s recent praise has moved it back toward the top of the pile. He wrote: “Every so often a book comes along that leaves you dizzy with wonder that you haven’t read it before. Why haven’t people been pressing [this] on me since I was old enough to read?”

A year or more ago, I was browsing at the Barnes & Noble in Union Square (one of the best bookstores in New York for browsing), and I came across a novel called War with the Newts by Karel Čapek. And I bought it, because, in case you hadn’t noticed, it’s called War with the Newts. Like many books I buy, I haven’t gotten around to reading it yet, but John Self’s recent praise has moved it back toward the top of the pile. He wrote: “Every so often a book comes along that leaves you dizzy with wonder that you haven’t read it before. Why haven’t people been pressing [this] on me since I was old enough to read?”

Originally published in 1936, the novel is what the Washington Post Book World called, “A send-up of multiple early-20th-century isms.” One sentence from the back of the book sums things up: “Man discovers a species of giant, intelligent newts and learns to exploit them so successfully that the newts gain enough skills and arms to challenge man’s place at the top of the animal kingdom.” Hijinks, I feel certain, ensue.

Čapek was a Czech author who was only 48 when he died on Christmas in 1938. According to Wikipedia, he or his brother came up with the word “robot.”

The great cover featured at the top of this post is from a 1955 paperback. With a title like this, it’s unsurprising that there are other fun covers, like this one and this one, which are all far preferable to the blandness on the edition I own.

Monday, June 14th, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Tom Bissell’s latest book, Extra Lives, details the author’s love affair with video games, and investigates whether or not the games can be considered art. Abigail Deutsch says, “Like a chat with a smart friend who may have fallen for a ditz, Extra Lives provides a lesson in articulate ambivalence.” And Jonathan Last says that Bissell is “so descriptively alert that his accounts of pixelated derring-do may well interest even those who are immune to the charm of video games.” . . . Off the top of my head, I can think of four or five recent books about noise and silence. Nicholas Carr reviews one of them, In Pursuit of Silence by George Prochnik: “Hearing loss, Prochnik reports, is becoming an epidemic, and yet, seeking refuge from noise in more noise, we continue to jack up the volume.” . . . Sylvia Brownrigg calls Ann Beattie’s new novella “a deceptively complex work, one that touches on the intricate strangenesses of friendship and marriage, and of life in that indulgent period [the 1980s].” . . . As a child, poet Paul Guest was in a bicycle accident that left him a quadriplegic. Christopher Beha reviews Guest’s new memoir, which includes an account of the accident “harrowing in its matter-of-factness.” . . . Peter Kramer reviews How Pleasure Works in the form of a conversation with the book’s author, Paul Bloom.

Tom Bissell’s latest book, Extra Lives, details the author’s love affair with video games, and investigates whether or not the games can be considered art. Abigail Deutsch says, “Like a chat with a smart friend who may have fallen for a ditz, Extra Lives provides a lesson in articulate ambivalence.” And Jonathan Last says that Bissell is “so descriptively alert that his accounts of pixelated derring-do may well interest even those who are immune to the charm of video games.” . . . Off the top of my head, I can think of four or five recent books about noise and silence. Nicholas Carr reviews one of them, In Pursuit of Silence by George Prochnik: “Hearing loss, Prochnik reports, is becoming an epidemic, and yet, seeking refuge from noise in more noise, we continue to jack up the volume.” . . . Sylvia Brownrigg calls Ann Beattie’s new novella “a deceptively complex work, one that touches on the intricate strangenesses of friendship and marriage, and of life in that indulgent period [the 1980s].” . . . As a child, poet Paul Guest was in a bicycle accident that left him a quadriplegic. Christopher Beha reviews Guest’s new memoir, which includes an account of the accident “harrowing in its matter-of-factness.” . . . Peter Kramer reviews How Pleasure Works in the form of a conversation with the book’s author, Paul Bloom.

Friday, June 11th, 2010

Icebreaker

The opening sentence of Fever Pitch by Nick Hornby:

I fell in love with football as I was later to fall in love with women: suddenly, inexplicably, uncritically, giving no thought to the pain or disruption it would bring with it.

Wednesday, June 9th, 2010

In the Ether

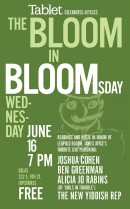

Bloomsday is a week from today, and that means fans of James Joyce’s Ulysses are planning their celebrations to mark the event. Tablet Magazine is hosting a night at Solas, a very nice bar in New York’s East Village, to celebrate Leopold Bloom’s Jewishness. Novelists Ben Greenman and Joshua Cohen will read, actors from the New Yiddish Repertory Theater will perform a scene from the novel that they have translated into Yiddish, and “Ulysses in Five Minutes” will sum things up for those who haven’t read the book. (Like, somewhat embarrassingly, me.) . . . And WBAI in New York will broadcast a night of readings from the book, featuring Alec Baldwin, Paul Muldoon, Bob Odenkirk, and many others. . . . Nicholas Carr answers a few questions about his new book, and about his writing life in general: “My dream is to disappear for ten years and then reappear, in sandals and a beard, with a strange and wondrous thousand-page manuscript written in longhand. Something tells me that’s not going to happen.” . . . John Eklund advises not to be fooled by the title of The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, which Yale has just republished: “Lurking beneath the bland, academic sounding title is one of the wisest, slyest, wittiest pieces of writing on books and readers I’ve ever encountered.” . . . Austin Ratner considers how and why historical fiction can work: “What matters is not whether a novel or story’s setting precedes the date of writing, but whether the writer’s research into setting has upset the balance of narrative elements so that structure, character, etcetera become subordinate to large hair balls of superfluous detail . . .” . . . Inspired by a book by Henry Houdini, the Caustic Cover Critic went looking for more and found “a number of funky old books intended to draw back the veil and expose the craft [of magic] to the general public.”

Bloomsday is a week from today, and that means fans of James Joyce’s Ulysses are planning their celebrations to mark the event. Tablet Magazine is hosting a night at Solas, a very nice bar in New York’s East Village, to celebrate Leopold Bloom’s Jewishness. Novelists Ben Greenman and Joshua Cohen will read, actors from the New Yiddish Repertory Theater will perform a scene from the novel that they have translated into Yiddish, and “Ulysses in Five Minutes” will sum things up for those who haven’t read the book. (Like, somewhat embarrassingly, me.) . . . And WBAI in New York will broadcast a night of readings from the book, featuring Alec Baldwin, Paul Muldoon, Bob Odenkirk, and many others. . . . Nicholas Carr answers a few questions about his new book, and about his writing life in general: “My dream is to disappear for ten years and then reappear, in sandals and a beard, with a strange and wondrous thousand-page manuscript written in longhand. Something tells me that’s not going to happen.” . . . John Eklund advises not to be fooled by the title of The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, which Yale has just republished: “Lurking beneath the bland, academic sounding title is one of the wisest, slyest, wittiest pieces of writing on books and readers I’ve ever encountered.” . . . Austin Ratner considers how and why historical fiction can work: “What matters is not whether a novel or story’s setting precedes the date of writing, but whether the writer’s research into setting has upset the balance of narrative elements so that structure, character, etcetera become subordinate to large hair balls of superfluous detail . . .” . . . Inspired by a book by Henry Houdini, the Caustic Cover Critic went looking for more and found “a number of funky old books intended to draw back the veil and expose the craft [of magic] to the general public.”

Wednesday, June 9th, 2010

A Hunger for the Promotion of This Book to End Sometime Before the 22nd Century

I’m still working on an increasingly sprawling review of David Shields’ Reality Hunger, though I’m starting to wonder if it wouldn’t be more interesting to just mention it from time to time on the blog for eternity. The world’s first asymptotic book review.

In any case, Shields is still flogging his latest for all it’s worth, recently interviewed by Michael Silverblatt on Bookworm. (Silverblatt is another story, for another day. It seems that people take him seriously, but I find him exceedingly off-putting and sycophantic. He’s interviewed in the new issue of The Believer.)

Shields appeared on the show with Ander Monson (full show embedded below), whose recent memoir, Vanishing Point: Not a Memoir, fits Shields’ narrow, quirky definition of what’s acceptable to read, and which Shields raved about in the New York Times. Monson comes off a little better in the interview, though at one point he says, “One of the metaphors that I was trying to think about is, ‘In what way is self like a wiki?’” And that’s when I almost pulled the emergency brake.

Monson also says that thinking about his own work is “itself the work,” which is a pretty good definition of work that has limited appeal to me, though I’m not going to write (or rather, plagiarize) a manifesto about my preferences.

I will say this: Shields now has me wondering if all of this is a stunt, and if maybe the final joke will be on me and other detractors. He talks about trying to “redefine nonfiction upward;” recommends “rescu[ing] nonfiction as art away from standard memoir;” talks about Danger Mouse’s Grey Album, which was released six long years ago, as if it’s news; and acknowledges T. S. Eliot’s battles with accusations of plagiarism without betraying any thought that maybe this makes his own book less radical than he thinks it is. OK, OK, the show:

(Via The Casual Optimist)

Tuesday, June 8th, 2010

David Markson, 1927-2010

A belated post about the recent death of celebrated experimental writer David Markson. Here’s the first paragraph of the obituary written by Bruce Weber in the New York Times:

A belated post about the recent death of celebrated experimental writer David Markson. Here’s the first paragraph of the obituary written by Bruce Weber in the New York Times:

David Markson, whose wry, elliptical novels probing the scattered mind of the artist and the unruly craft of making art were frequently called postmodern and experimental and almost always surprisingly engaging and underappreciated, died Friday in his Greenwich Village apartment. He was 82.

I finally got around to reading Wittgenstein’s Mistress, about a woman who’s either insane or the last surviving person on earth—or perhaps both—a couple of years ago, and the brutal repetition of its particular experiment wore me down after a while. But I’ll certainly read more of his work.

Sarah Weinman, a fan and acquaintance of Markson, rounds up other reaction to his passing, and remembers writing about two of his early novels, more-or-less-conventional crime stories starring a detective named Harry Fannin:

Markson clearly wrote the books for money, and a way to make use of some of the genre knowledge he’d gleaned working as an editor for Dell, then one of the pulp paperback mills that couldn’t quite hold a candle to Fawcett Gold Medal’s granddaddy status. But not unlike John Banville’s pseudonymous mystery novels, the Fannin books couldn’t help but betray the rudimentary building blocks of themes and topics Markson spent his entire later career working through: baseball, bad puns, William Gaddis’ The Recognitions

, and the writer’s struggle for relevance and the artist’s relationship to creative pursuits.

Below is a clip of Markson reading from The Last Novel at the 92nd Street Y in November 2007. In his introductory remarks, he talks about his work, perhaps intentionally slipping between the singular (about that particular book) and the plural:

As a few of you know, the few of you who have read it—I see my royalty statements; the few of you—my books have no dramatic scenes, no incidents, no events, no sections that stand alone, there aren’t even any chapters. It just starts at the beginning and goes on to the end. And 98 and a half percent—that’s not really a guess, I think I counted—98 and a half percent of the book is composed of a sequence of intellectual odds and ends about writers, about painters, about composers, about performers, even sports figures. . . . There are certain themes that run through, of course, mainly about the life of the writer, the artist, and death is a major theme.

Tuesday, June 8th, 2010

Combat Boredom

Mark Athitakis has some interesting things to say about the reading he got done on a recent trip to Nova Scotia:

I left with Tom Bissell’s Extra Lives, a collection of personal essays, reporting, and essays on video games, and Karl Marlantes’ Matterhorn, a hefty novel set during the Vietnam War. The two have a lot to say to each other, it turns out. Both to a large extent wrestle with the same question: How do you tell a story about combat without boring people?

Monday, June 7th, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Anthony Doerr says that Charlie Smith’s new novel, about lovers who “spiral through a demonic and cataclysmic romance that incinerates most everyone around them,” is “as blissed-out and excessive and aimless as its protagonist. It is both beautiful and disastrous. And its absolute apartness — in its gasping energy, in the ravishing excess of Charlie Smith’s prose — is something to be celebrated.” . . . Michael Agger says that Nicholas Carr’s latest, about the way the Internet is changing our brains, is “a Silent Spring for the literary mind.” And Daniel Menaker calls the same book “required reading for anyone who wants a cogent, comprehensive, and thoroughly researched statement of the techno-fears that, in however inchoate a way, many of us have harbored for going on a few decades now.” . . . Michael Kimmelman, a bit belatedly but intelligently, writes about two tennis books: Andre Agassi’s memoir and a history of the 1937 Davis Cup. . . . Paul Batchelor is impressed by Simon Armitage’s Seeing Stars, “a wildly inventive mix of satire, fantasy, comedy and horror,” saying that “there is more wit and adventure on display here than you’ll find in many poets’ careers.” . . . Laura Miller wonders why young readers are so interested in dystopian fiction.

Anthony Doerr says that Charlie Smith’s new novel, about lovers who “spiral through a demonic and cataclysmic romance that incinerates most everyone around them,” is “as blissed-out and excessive and aimless as its protagonist. It is both beautiful and disastrous. And its absolute apartness — in its gasping energy, in the ravishing excess of Charlie Smith’s prose — is something to be celebrated.” . . . Michael Agger says that Nicholas Carr’s latest, about the way the Internet is changing our brains, is “a Silent Spring for the literary mind.” And Daniel Menaker calls the same book “required reading for anyone who wants a cogent, comprehensive, and thoroughly researched statement of the techno-fears that, in however inchoate a way, many of us have harbored for going on a few decades now.” . . . Michael Kimmelman, a bit belatedly but intelligently, writes about two tennis books: Andre Agassi’s memoir and a history of the 1937 Davis Cup. . . . Paul Batchelor is impressed by Simon Armitage’s Seeing Stars, “a wildly inventive mix of satire, fantasy, comedy and horror,” saying that “there is more wit and adventure on display here than you’ll find in many poets’ careers.” . . . Laura Miller wonders why young readers are so interested in dystopian fiction.

Monday, June 7th, 2010

Hostility to Reading

In The Nation, John Palattella has a smart cover article on the state of book reviewing in print and on the web. Among other angles, he focuses on the sad state that was the 1990s:

In The Nation, John Palattella has a smart cover article on the state of book reviewing in print and on the web. Among other angles, he focuses on the sad state that was the 1990s:

In 1999 Steve Wasserman was three years into his tenure as the editor of The Los Angeles Times Book Review, and that July he published a review of Richard Howard’s new translation of Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma. The reason was simple: Howard is among the best translators of French literature. As Wasserman explained several years ago in a memoir of his days at the Los Angeles Times published in the Columbia Journalism Review, the review of the book, written by Edmund White, was stylish and laudatory. The Monday after the piece ran, the paper’s editor summoned Wasserman to his office and admonished him for running an article about “another dead, white, European male.” But the paper’s readers in Los Angeles thought otherwise. Soon after the review appeared, local sales of the book took off; national sales did too when other publications reviewed the book. The New Yorker ended up printing a “Talk of the Town” item that traced the book’s unexpected success to The Los Angeles Times Book Review. In his memoir, Wasserman relates a similar story about Carlin Romano, then the books critic at the Philadelphia Inquirer, who was scolded by an editor for running as the cover story of his section a review of a new translation of Tirant Lo Blanc, a Catalan epic beloved by Cervantes. “Have you gone crazy?” the editor asked. “Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of America’s newspapers in the 1990s,” Romano reflected, “is their hostility to reading in all forms.”

Saturday, June 5th, 2010

1-900-HITCH22

An interview with Christopher Hitchens in tomorrow’s New York Times Magazine, about his new memoir

An interview with Christopher Hitchens in tomorrow’s New York Times Magazine, about his new memoir, among other subjects, ends with this:

Did you write the book for money?

Of course, I do everything for money. Dr. Johnson is correct when he says that only a fool writes for anything but money. It would be useful to keep a diary, but I don’t like writing unpaid. I don’t like writing checks without getting paid.I trust you answer the e-mail of your friends at no charge.

I haven’t got to the point yet where phone calls and e-mails are billable, but I am working on it. That would be happiness defined for me. What I’m hoping is to get a 900 number, so I can tell all my friends, “Call me back on my 900 number: 1-900-HITCH22.” I can talk for a long time.But who would want to listen?

That would be the 900-number test.

Friday, June 4th, 2010

McCracken on Austin and What’s Next

I lived in Texas for 12 years (Dallas and San Antonio), and still have family and several close friends there, including in Austin. But if and when I daydream about living somewhere other than New York, Austin rarely exerts a strong appeal. This is because I’m a cold-weather person. It’s in the 80s in Brooklyn right now, and I feel like someone is going to have to remove me from the sidewalk with a pipette by day’s end. Though Texas is a perfectly nice place to live in many ways, there are about eight months a year there where I feel like a lizard baking on a rock.

Novelist (and memoir and story writer) Elizabeth McCracken recently relocated to Austin with her husband and two kids, and she talks about the city and her work with Jody Seaborn at the American-Statesman:

Novelist (and memoir and story writer) Elizabeth McCracken recently relocated to Austin with her husband and two kids, and she talks about the city and her work with Jody Seaborn at the American-Statesman:

The new novel McCracken is working on is tentatively titled Let Your Heart Become Iron. She understandably didn’t want to say too much about the novel other than to note that it’s about a female weightlifter, is “slightly less realistic” than The Giant’s House

and Niagara Falls All Over Again

, and is mostly set in the 1970s. She says it shares with her previous novels her need to hit on a subject that can obsess her, whether it be gigantism, vaudeville or weightlifting.

McCracken is also asked whether she finds novels or short stories easier to write (she’s currently completing a second collection of stories as well): “ ‘Novel writing,’ she says, without hesitation. ‘The novel is just a much more forgiving form.’ ”

Friday, June 4th, 2010

Beverly Cleary to Jonathan Safran Foer: Get Off My Lawn.

In response to the New Yorker’s recent announcement of its “20 Under 40″ list, of notable fiction writers younger than 40, the blog Ward Six has announced its list of “Ten Over 80.” An initially funny and ultimately welcome idea, the list includes John Barth, Paula Fox, and J. P. Donleavy, whose story “The Mad Molecule” starts like this:

In response to the New Yorker’s recent announcement of its “20 Under 40″ list, of notable fiction writers younger than 40, the blog Ward Six has announced its list of “Ten Over 80.” An initially funny and ultimately welcome idea, the list includes John Barth, Paula Fox, and J. P. Donleavy, whose story “The Mad Molecule” starts like this:

I woke on that terrible day and mixed the shredded apple in my raw porridge oats and poured on the cream. I know what’s good for me. I put on the shoes with the golfer’s soles, walked silently down the stairs and out into a great blue sky and along the river’s warm sweet smell.

Friday, June 4th, 2010

The Art of the Stunt

Creative Nonfiction offers step-by-step instructions to aspiring “stunt writers.” You know, the kind of thing A. J. Jacobs has done so much that for his latest book he sheds the pretense and just explicitly calls himself a guinea pig. Step 3 (of 11) is “Convince an Editor/Publisher to Let You Write About (and, Ideally, to Pay For) Your Stunt”:

Creative Nonfiction offers step-by-step instructions to aspiring “stunt writers.” You know, the kind of thing A. J. Jacobs has done so much that for his latest book he sheds the pretense and just explicitly calls himself a guinea pig. Step 3 (of 11) is “Convince an Editor/Publisher to Let You Write About (and, Ideally, to Pay For) Your Stunt”:

One day, Barbara Ehrenreich was having lunch with Lewis Lapham, then editor of Harper’s. As she tells the story, their talk drifted to poverty and to how women, especially, would fare under welfare reform and support themselves and, often, families on minimum wage. Ehrenreich suggested that someone should do “the old-fashioned kind of journalism—you know, go out there and try it for themselves.” And “Lapham got this crazy-looking half smile on his face and ended life as I knew it, for long stretches at least, with the single word ‘You.’” [George] Plimpton pitched his idea for a series of sports-related escapades to the editor of Sports Illustrated, who gave him the go-ahead to pitch baseballs to All-Stars and later even put up a cash prize for the “winning” batters, but warned, “Seems to me that your big problem isn’t going to be arranging these . . . er . . . matches, or writing about what you go through, but getting through everything in one piece . . . in a word: survival. I would advise getting in shape.” Which turned out to have been good advice—if only Plimpton had paid heed.

Wednesday, June 2nd, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources. It normally appears on Mondays.

At n+1, Alexander Provan writes a thorough critique of “lyrical essayist” John D’Agata’s new book, which frequently alters facts on a whim: “[D’Agata] seems to forget that the inability of language or representations to capture our experience of the world is a signal problem of art in the modern era, not just a characteristic of the essay—and that tackling this aporia does not in itself qualify something as art, nor make it interesting.” Plus this: “It is often difficult to shake the feeling that D’Agata is addressing those who have paid a large sum of money to have their creative personas validated.” Ouch. . . . In the new issue of Open Letter Monthly, Rohan Maitzen reads Jane’s Fame: How Jane Austen Conquered the World, and wonders if Austen remains a posthumous superstar because of “her representative standing as an icon for a nostalgically imagined past.” . . . Gary Lutz admires a short new book by Jane Unrue about the daughter of a washed-up actress: “With just over one hundred pages, some of them hosting no more than a wee phrase or the clarion burst of a sentence, and most of them giving out well shy of the bottom margins, the novel, though slender, is emotionally thorough, dense but not crammed, and unnoisily original in the bloodbeat and quiver of its prose.” . . . The Economist reviews a new social history of Iceland: “The story is not wholly pleasant. Even readers with strong stomachs will find them tested.” . . . Tim Rutten heaps praise upon Julie Orringer’s first novel, set against the Holocaust: “It’s hard to imagine a fictional setting more heavily strewn with literary and historical mines, but Orringer traverses this perilous rhetorical terrain with remarkable — and, more important, convincing, self-possession.” . . . Not sure when it’s being published in the U.S., but Jonathan Coe’s new novel is out in the UK, and Sean O’Brien has a funny image for it: “Jonathan Coe, acclaimed and admired, seems to have unwritten his novel in the act of writing it, plunging into a canyon like Wile. E. Coyote when he discovers that his tightrope only has one end secured.”

At n+1, Alexander Provan writes a thorough critique of “lyrical essayist” John D’Agata’s new book, which frequently alters facts on a whim: “[D’Agata] seems to forget that the inability of language or representations to capture our experience of the world is a signal problem of art in the modern era, not just a characteristic of the essay—and that tackling this aporia does not in itself qualify something as art, nor make it interesting.” Plus this: “It is often difficult to shake the feeling that D’Agata is addressing those who have paid a large sum of money to have their creative personas validated.” Ouch. . . . In the new issue of Open Letter Monthly, Rohan Maitzen reads Jane’s Fame: How Jane Austen Conquered the World, and wonders if Austen remains a posthumous superstar because of “her representative standing as an icon for a nostalgically imagined past.” . . . Gary Lutz admires a short new book by Jane Unrue about the daughter of a washed-up actress: “With just over one hundred pages, some of them hosting no more than a wee phrase or the clarion burst of a sentence, and most of them giving out well shy of the bottom margins, the novel, though slender, is emotionally thorough, dense but not crammed, and unnoisily original in the bloodbeat and quiver of its prose.” . . . The Economist reviews a new social history of Iceland: “The story is not wholly pleasant. Even readers with strong stomachs will find them tested.” . . . Tim Rutten heaps praise upon Julie Orringer’s first novel, set against the Holocaust: “It’s hard to imagine a fictional setting more heavily strewn with literary and historical mines, but Orringer traverses this perilous rhetorical terrain with remarkable — and, more important, convincing, self-possession.” . . . Not sure when it’s being published in the U.S., but Jonathan Coe’s new novel is out in the UK, and Sean O’Brien has a funny image for it: “Jonathan Coe, acclaimed and admired, seems to have unwritten his novel in the act of writing it, plunging into a canyon like Wile. E. Coyote when he discovers that his tightrope only has one end secured.”

Wednesday, June 2nd, 2010

Justin Cronin Has Not Read Twilight

Next week, I’ll be posting a review of Justin Cronin’s The Passage

Next week, I’ll be posting a review of Justin Cronin’s The Passage, a nearly 800-page novel, the first in a planned trilogy, about vampires created by a military experiment gone awry and a girl who may be charged with saving the world. It is, admittedly, not the kind of thing I normally read. It’s also not the kind of thing Cronin has normally written. Today, the New York Times writes about the book and Cronin’s influences:

“I have not read Twilight,” Mr. Cronin, 47, said of the Stephenie Meyer book that kick-started the recent public obsession with the paranormal, adding that he was reared on vampire comics, the 1960s television soap opera Dark Shadows and the 1931 film version of Dracula, with Bela Lugosi. “My relationship to vampire material definitely predates the recent renaissance.”

In this video clip, Cronin discusses the project, and seems giddy at the departure from his previous, quieter novels, laughing through parts of this description of The Passage: “Obviously, it has some aspects of a horror novel; it is a dystopia novel; it is a post-apocalyptic, speculative fiction; it’s a thriller; it has an FBI agent in it; it has an orphaned girl who can talk to animals; it has not one, but two runaway trains.”

Wednesday, June 2nd, 2010

A Quarterly Goes Daily

Recently appointed editor Lorin Stein has started a blog at The Paris Review. Among other things, the blog will dedicate June to Terry Southern, the novelist/satirist/screenwriter whose work was published in the founding issue of the Review. From Stein’s note introducing the blog:

Since its founding in 1953, The Paris Review has devoted itself to publishing “the good writers and good poets,” regardless of creed or school or name-recognition. In that time the Review has earned a reputation as the chief discoverer of what is newest and best in contemporary writing.

But a quarterly only comes out…well, you know. We have been looking for a way to keep in touch with our readers between issues, and to call attention to our favorite writers and artists in something close to real time. If the Review embodies a sensibility, this Daily will try, in a casual and haphazard and at times possibly frivolous way, to put that sensibility into words.

Taking inspiration from the Review’s founding editor, George Plimpton, our mode will be participatory journalism, our beat the arts. We will write about what we love, not as critics, but as participants—as amateurs in the Plimptonian sense of the word. That anyway is our aim. Furthermore we hope that you will enjoy the Daily and—most of all—that you’ll write in and tell us what you think.