This time of year, as the days get shorter, the nights longer and more crisp, even city dwellers can feel the inherent tension of the season: after a hard summer of work, the harvest is in, and bountiful, but — quickly — it must be put up, canned, dried, stored, made ready for the dark months ahead, for winter ravens at the door, and the weak and the old and the ill-prepared will not likely see the spring.

No wonder the dead walk the earth in late October. No wonder fitful spirits wander. No wonder, as the harvest moon ices over to a steely, unwelcoming blue, that thoughts of mortality grip us, and the boundaries between this world and the next weaken for a while.

Halloween is here. But before you lay in some cider and lock the door, stop by your library with this list in hand: recommendations and favorites from a number of writers and critics who have one thing in common — they love a creepy tale. —Levi Stahl

Algernon Blackwood’s “The Man Whom the Trees Loved,” from Pan’s Garden: A Volume of Nature Stories (1912)

Selected by James Hynes

The plot of Algernon Blackwood’s story “The Man Whom the Trees Loved” can be summed up in a sentence: A retired forester and his wife, David and Sophia Bittacy, live at the edge of Britain’s New Forest, and the wife battles the collective will of the trees for the soul of her husband. Blackwood was one of the three greatest Edwardian writers of supernatural fiction (along with M. R. James and Arthur Machen), and his best stories traffic in his own syncretic mash-up of pantheism, English occultism, and paganism. He believed that the natural world has a consciousness that operates apart from and, at times, in direct opposition to that of humankind. In his best-known story, “The Willows,” which H. P. Lovecraft called the finest supernatural tale in English literature, nature is flat-out malevolent, as two canoeists discover when they barely escape a marshy region of the Danube. The effect of “The Man Whom the Trees Loved” is less terrifying, but more mysterious and heartbreaking. Not much happens in the story, and very little of it is dramatized — it violates “show, don’t tell” on almost every page — and the story works in large part through the cumulative power of Blackwood’s overripe late-Victorian prose. The story is told entirely from the point of view of Sophia, and in spite of the author’s rather sexist condescension toward her, she emerges as a tragic figure, a simple woman of deeply felt if conventional Christian faith, who battles the overwhelming hold the forest has on her husband with a kind of desperate courage. While the story lacks the galvanic jolt of fear you get in a conventional ghost story, it lingers much, much longer in the imagination, and after reading it, you will never hear the wind in the trees the same way again.

The plot of Algernon Blackwood’s story “The Man Whom the Trees Loved” can be summed up in a sentence: A retired forester and his wife, David and Sophia Bittacy, live at the edge of Britain’s New Forest, and the wife battles the collective will of the trees for the soul of her husband. Blackwood was one of the three greatest Edwardian writers of supernatural fiction (along with M. R. James and Arthur Machen), and his best stories traffic in his own syncretic mash-up of pantheism, English occultism, and paganism. He believed that the natural world has a consciousness that operates apart from and, at times, in direct opposition to that of humankind. In his best-known story, “The Willows,” which H. P. Lovecraft called the finest supernatural tale in English literature, nature is flat-out malevolent, as two canoeists discover when they barely escape a marshy region of the Danube. The effect of “The Man Whom the Trees Loved” is less terrifying, but more mysterious and heartbreaking. Not much happens in the story, and very little of it is dramatized — it violates “show, don’t tell” on almost every page — and the story works in large part through the cumulative power of Blackwood’s overripe late-Victorian prose. The story is told entirely from the point of view of Sophia, and in spite of the author’s rather sexist condescension toward her, she emerges as a tragic figure, a simple woman of deeply felt if conventional Christian faith, who battles the overwhelming hold the forest has on her husband with a kind of desperate courage. While the story lacks the galvanic jolt of fear you get in a conventional ghost story, it lingers much, much longer in the imagination, and after reading it, you will never hear the wind in the trees the same way again.

James Hynes’ own ghost story, “Backseat Driver,” has just been published in the anthology Ghost Writers, edited by Keith Taylor and Laura Kasischke, from Wayne State University Press.

*****

John Wyndham’s “Mars,” from The Outward Urge (1959)

Selected by James Morrison

Let’s set the scene: You’re one of three crew members on the first manned mission to Mars. As you land, after a long journey, something goes wrong; there’s an accident. One crew member is killed, and the other suffers a severe head injury. The only one alive and conscious, you’re now the most isolated human being in history, at least 30 million miles from home and help, on a lifeless desert planet. This is the situation facing Brazilian astronaut Geoffrey Trunho in John Wyndham’s “Mars.” So it’s a relief, at least at first, when the other survivor finally comes round.

Let’s set the scene: You’re one of three crew members on the first manned mission to Mars. As you land, after a long journey, something goes wrong; there’s an accident. One crew member is killed, and the other suffers a severe head injury. The only one alive and conscious, you’re now the most isolated human being in history, at least 30 million miles from home and help, on a lifeless desert planet. This is the situation facing Brazilian astronaut Geoffrey Trunho in John Wyndham’s “Mars.” So it’s a relief, at least at first, when the other survivor finally comes round.

Camilo was now awake — not only awake, but sitting up on his couch, regarding me with nervous intensity.

“I don’t like Martians,” he said.

I looked at him carefully. His expression was serious, and not at all friendly.

“I don’t suppose I would, either,” I admitted, keeping my tone matter-of-fact.

His expression became puzzled, then wary. He shook his head.

“Very cunning lot, you Martians,” he remarked.

The Outward Urge is an oddity in John Wyndham’s oeuvre, a novel in short stories set over a period of 200 years, and quite different from his usual present-day explorations of various apocalypses and their aftermaths — including the two unqualified masterpieces The Chrysalids and The Day of the Triffids.

He was presumably a little uncertain about the direction he’d taken in The Outward Urge, publishing it as written by John Wyndham and Lucas Parkes (both drawn from his own unwieldy birth name, John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris), so that he could attribute any problems to his imaginary co-author. And though the book does have its faults, in “Mars” it also has a tremendous creepy story of isolation and paranoia: the sort of story that reinforces the fact that for all the monsters and ghosts we can imagine, it’s other human beings and what they’re capable of that is truly frightening.

When I woke, there was daylight outside the ports, and Camilo standing beside one of them looking out . . .

“I don’t like Mars.”

“Nor do I,” I agreed. “But then, I never expected to.”

“Funny thing,” he said. “I got it into my head last night that you were a Martian. Sorry.”

“You had a nasty knock,” I told him. “Must have shaken you up quite a bit. How are you feeling now?”

“Oh, all right — bit of a muzzy headache. It’ll pass. Damn silly of me thinking you were a Martian. You’re not a bit like one, really . . .”

James Morrison is a writer and editor from Australia. He blogs at Caustic Cover Critic and publishes books under the imprint of Whisky Priest.

*****

Five for Frightening

Selected by Ed Park

Think you’re tough? Don’t scare easily — certainly not over something as old-media as a book? Try this triple shot, to be downed greedily in a single sitting: Edgar Allan Poe’s “William Wilson” (1839), H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Outsider” (1920), and Stephen King’s “Strawberry Spring” (1978). Not only does the spine-tingle quotient crescendo as you move across that span of nearly 150 years, but the writers — three undisputed masters — seem to be in conversation with each other. Without giving too much away, let’s just say that the W’s in “William Wilson” are significant in Lovecraft’s and King’s stories as well: double yous, hinting that your identity isn’t nearly as fixed as you think. As a coda, program your mp3 alarm clock to play Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror” at precisely the instant you finish King’s story — in my opinion, the best thing he’s ever written. If that’s not enough, read (you still have time, the night is young) Sara Gran’s Come Closer. Now you are definitely screaming your head off.

Think you’re tough? Don’t scare easily — certainly not over something as old-media as a book? Try this triple shot, to be downed greedily in a single sitting: Edgar Allan Poe’s “William Wilson” (1839), H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Outsider” (1920), and Stephen King’s “Strawberry Spring” (1978). Not only does the spine-tingle quotient crescendo as you move across that span of nearly 150 years, but the writers — three undisputed masters — seem to be in conversation with each other. Without giving too much away, let’s just say that the W’s in “William Wilson” are significant in Lovecraft’s and King’s stories as well: double yous, hinting that your identity isn’t nearly as fixed as you think. As a coda, program your mp3 alarm clock to play Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror” at precisely the instant you finish King’s story — in my opinion, the best thing he’s ever written. If that’s not enough, read (you still have time, the night is young) Sara Gran’s Come Closer. Now you are definitely screaming your head off.

No?

OK. Time for the secret weapon: Bridget Clerkin’s “Twenty Questions,” in McSweeney’s #34.

Ed Park is the author of the novel Personal Days. He is also, with Levi Stahl, co-librarian of the Invisible Library. You can follow him on Twitter: @tharealedpark.

*****

Joan Aiken’s “As Gay as Cheese,” from The Far Forests: Tales of Romance, Fantasy, and Suspense (1977)

Selected by Andrea Janes

Joan Aiken’s “As Gay As Cheese” concerns a Cornish barber named Mr. Pol who has the uncanny ability to foretell a person’s death merely by running his hands through their hair. He rents the room above his rickety shop to a surly artist who panders to the tourist trade with seascape watercolors. Mr. Pol is an untroubled, fatalistic soul, the very embodiment of equanimity, accepting his strange gift as just one of those things. He whistles cheerfully and speaks in homely cliches as he cuts hair, sweeps floors, and putters around the shop: “I’m as bright as a pearl this morning,” he’ll say, or, “I’m as gay as cheese today.”

Joan Aiken’s “As Gay As Cheese” concerns a Cornish barber named Mr. Pol who has the uncanny ability to foretell a person’s death merely by running his hands through their hair. He rents the room above his rickety shop to a surly artist who panders to the tourist trade with seascape watercolors. Mr. Pol is an untroubled, fatalistic soul, the very embodiment of equanimity, accepting his strange gift as just one of those things. He whistles cheerfully and speaks in homely cliches as he cuts hair, sweeps floors, and putters around the shop: “I’m as bright as a pearl this morning,” he’ll say, or, “I’m as gay as cheese today.”

One morning a young couple, summer visitors, comes into the shop. Brian is an emotionally abusive bastard who strides in demanding a shave while ordering Mr. Pol to give Fanny a haircut (“You look like a Scotch terrier,” he says to her); Fanny is a scared and gentle fawn of a woman. Throughout, Brian is very anxious to take a certain cliff walk to Pengelly. In fact, he seems extremely focused on this.

As Mr. Pol cuts Fanny’s hair, he feels a shudder run through him like an electric shock. With horror, he sees her floating in the water, bits of seaweed wreathing her face, her thin arm floating out into the water. “Death by drowning,” he foretells. “And so soon.”

The story ends with the surly artist running downstairs too late to sell a painting to Brian and Fanny. He notices Mr. Pol’s pallid face as the barber stares after the departing couple. “What’s the matter?” he asks. “Nothing,” Mr. Pol says. “I’m as gay as cheese.”

I love this story because it says so much while stating so little. With only a few comments and pointed insults, we are given full understanding of Brian’s character; Fanny’s frightened reactions sketch in the rest. And then there is Mr. Pol, who knows he is powerless to stop what happens; his powers do not grant him the right to intervene, and he must quietly let life — and death — run its course, as a river runs to the sea.

Andrea Janes is the author of Boroughs of the Dead, a collection of 10 short horror stories set in and around New York City. She blogs at Spinster Aunt, and you can follow her on Twitter: @spinsteraunt.

*****

Arthur Conan Doyle (1890), Franz Kafka (1919), Jorge Luis Borges (1949): Three Stories

Selected by John Crowley

Scary stories come in many flavors: the ghastly, the haunting, the loathsome. I can’t decide. Conan Doyle’s “The Sign of Four”? When I first read it (age 10) it was terrifying in the awful sense of paranoid possibility it awoke. I didn’t understand it was a mystery that would be solved; for all I knew it would simply go on generating horrid complications forever, and I didn’t see that the ending resolved anything. Much later, I read Kafka’s “A Country Doctor” — the most disturbing dream-story I know; reading it is almost identical to dreaming, imbued with all the unsettling sense of compelling but unresolvable meaning. But I think the prize would go to Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Zahir.” By chance a man picks up a coin, the latest instance of the Zahir: a demonic thing that, once seen, can never be forgotten and which in the end replaces everything else in the mind. It’s not the only one of Borges’ stories that opens into what can only be called a claustrophobic infinity at the end, but it’s the most terrifying.

Scary stories come in many flavors: the ghastly, the haunting, the loathsome. I can’t decide. Conan Doyle’s “The Sign of Four”? When I first read it (age 10) it was terrifying in the awful sense of paranoid possibility it awoke. I didn’t understand it was a mystery that would be solved; for all I knew it would simply go on generating horrid complications forever, and I didn’t see that the ending resolved anything. Much later, I read Kafka’s “A Country Doctor” — the most disturbing dream-story I know; reading it is almost identical to dreaming, imbued with all the unsettling sense of compelling but unresolvable meaning. But I think the prize would go to Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Zahir.” By chance a man picks up a coin, the latest instance of the Zahir: a demonic thing that, once seen, can never be forgotten and which in the end replaces everything else in the mind. It’s not the only one of Borges’ stories that opens into what can only be called a claustrophobic infinity at the end, but it’s the most terrifying.

I see that the three define a flavor: dreadful endlessness, damnation. “A false alarm on the night bell once answered — it cannot be made good, not ever.”

John Crowley is the author of many novels, including the Aegypt tetralogy, Little, Big, and Four Freedoms

. He blogs at John Crowley Little and Big.

*****

Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” from A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955)

Selected by John Eklund

I’ve burned through lots of literary enthusiasms in my life, but one constant has been Flannery O’Connor. I’ve read and re-read her Complete Stories for decades now, and they never get stale.

I’ve burned through lots of literary enthusiasms in my life, but one constant has been Flannery O’Connor. I’ve read and re-read her Complete Stories for decades now, and they never get stale.

She’s no horror writer, and she bristled at the “southern gothic” label. “Anything that comes out of the south is going to be called grotesque by the northern reader,” she wrote, “unless it is grotesque, in which case it’s going to be called realistic.”

But her incredible stories, each one a master class in the art, are often served up with a dash of menace — or so it seems to this Yankee reader. “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” is a story that makes me shudder every time I read it.

A crafty, strong-willed, slightly comical old woman — an O’Connor staple — tries to badger her family into re-routing a planned road trip so she can “visit some of her connections in East Tennessee.”

“Now look here, Bailey” she said, “see here, read this,” and she stood with one hand on her thin hip and the other rattling the newspaper at his bald head. “Here this fellow that calls himself The Misfit is aloose from the Federal Pen and headed toward Florida and you read here what it says he did to these people. Just you read it. I wouldn’t take my children in any direction with a criminal like that aloose in it.”

Her hotheaded son ignores her pleas, and the family — grandmother, wife, baby, and two bratty kids — set out toward Florida. I don’t think I’d be giving anything away to report that the grandmother was right to be worried. The shocking, bloodcurdling, weirdly mesmerizing denouement is something you won’t shake off anytime soon.

O’Connor once described a good short story as one with a plot twist that seems both utterly surprising and absolutely inevitable. A tall order when you think about it. “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” is a perfect example of O’Connor’s craft, and a chilling entry point to her oddly skewed world.

John Eklund is a sales representative for Harvard, Yale, and MIT university presses. He blogs at Paper Over Board.

*****

Walter de la Mare’s “Seaton’s Aunt” (1909)

Selected by Will Schofield

Walter de la Mare is a perennially underrated writer best known for his poems for children and the fabulously strange Memoirs of a Midget, which Harry Mathews called “a perfect, utterly original novel.”

Walter de la Mare is a perennially underrated writer best known for his poems for children and the fabulously strange Memoirs of a Midget, which Harry Mathews called “a perfect, utterly original novel.”

In “Seaton’s Aunt,” limp, sallow Arthur Seaton begs his only friend at school — Withers, the narrator — to stay with him overnight at the gloomy country estate where he lives with his fat old aunt, who gives him plenty of spending money and sweets when she’s not plotting to destroy him. The character of the repulsive, cynical aunt with her big head and “penthouse lids” conjures for me none other than Yubaba from Spirited Away.

Withers finds the lurking aunt creepy, but refuses to buy into Arthur’s conspiracies, and they survive a tense night in the echoing house. Years later, back on the estate in the Shadow of the Aunt, Arthur and his equally limp fiancee Alice entertain Withers for an evening. Arthur tries one last time to convince his friend about his aunt’s intentions: “I know that what we see and hear is only the smallest fraction of what is. I know she lives quite out of this. She talks to you; but it’s all make-believe. It’s all a ‘parlour game.’ She’s not really with you [. . .] She’s living on inside on what you’re rotten without. That’s what it is — a cannibal feast. She’s a spider.”

Withers meets the aunt once more, and I can say no more without spoiling the story. De la Mare doesn’t seem to care if you blame lonely paranoia or psychic vampirism for the events in his story, though he might argue that either is worthy of horror.

Will Schofield blogs as 50 Watts, and is one-third of Writers No One Reads.

*****

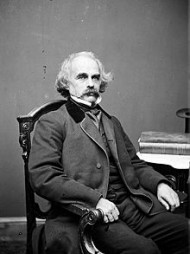

“My Kinsman, Major Molineux” by Nathaniel Hawthorne, from Twice-Told Tales (1837)

Selected by Joseph G. Peterson

If there were ever a ghost who wrote stories trying to convince himself that he had once been real, that ghost would surely have written in the prose of Nathaniel Hawthorne. His prose is famously uncanny, and haunting; or, to paraphrase Wallace Stevens, no one writes in ghostlier demarcations than Nathaniel Hawthorne.

If there were ever a ghost who wrote stories trying to convince himself that he had once been real, that ghost would surely have written in the prose of Nathaniel Hawthorne. His prose is famously uncanny, and haunting; or, to paraphrase Wallace Stevens, no one writes in ghostlier demarcations than Nathaniel Hawthorne.

His most famous short story collection, Twice-Told Tales suggests that an earlier telling haunts the teller of these tales. Hawthorne writes with such authority — as if he had been there in the early days of the original settlers of America — that you sometimes wonder if he isn’t himself some ghostly recurrence.

Both the rich eeriness of his language and the sense that he is a ghost lingering over the events of an earlier time are on wonderful display in his story “My Kinsman, Major Molineux.” This is a dark fable of what awaits the stranger who enters our cities. In this tale, Robin, a country yokel, travels five days through primeval woods to the town only to watch, by the antic glow of moonlight, Major Molineux, his kinsman and sole contact there, paraded through the village square at midnight by a rowdy mob. Major Molineux has been tarred and feathered, but when Robin laughs at the absurdity of his kinsman’s torture, he is told by one of the village gentleman that he has a bright future: “You may rise in the world.”

Whether you’re newly arrived or part of the gathering mob, this surreal tale about the dark side of American power continues to resonate.

Joseph G. Peterson is the author of the novel Beautiful Piece, the forthcoming novel Wanted: Elevator Man, and the forthcoming verse novel Inside the Whale.

*****

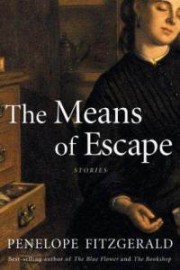

Penelope Fitzgerald’s “Desideratus,” from The Means of Escape (2000)

Selected by Levi Stahl

Penelope Fitzgerald’s fictional world is simultaneously wholly material — which allows her to recreate such lost places as Edwardian Oxford and pre-revolutionary Russia — and breathtakingly numinous. Her characters think and act as if they can understand and manipulate the world, but time and again they come up against the unlikely or the inexplicable, as if, amid her realism, Fitzgerald wants to remind us of all that lies beyond our ken. There are poltergeists and possibly even miracles; certainly, there is their counterweight, incipient, inescapable disaster. Fitzgerald’s sentences are concise to the point of asperity, her insights equally incisive, and their preferred end point is ambiguity.

Penelope Fitzgerald’s fictional world is simultaneously wholly material — which allows her to recreate such lost places as Edwardian Oxford and pre-revolutionary Russia — and breathtakingly numinous. Her characters think and act as if they can understand and manipulate the world, but time and again they come up against the unlikely or the inexplicable, as if, amid her realism, Fitzgerald wants to remind us of all that lies beyond our ken. There are poltergeists and possibly even miracles; certainly, there is their counterweight, incipient, inescapable disaster. Fitzgerald’s sentences are concise to the point of asperity, her insights equally incisive, and their preferred end point is ambiguity.

Which leads me to “Desideratus.” It tells of a poor boy, Jack Digby, who has one prized possession: a gilt medal, inscribed with his birthdate, an image of an angel, and a motto, Desideratus. He carries it with him everywhere. Fitzgerald — seer of disaster — dryly notes that “anything you carry about with you in your pocket you are bound to lose sooner or later,” and one late autumn day the medal goes missing.

Its journey from there and Jack’s pursuit of it resemble a dream verging on nightmare: it appears beneath a foot of ice in a deep puddle but disappears with the thaw, and Jack tracks its likely journey down a drainpipe into the yard of a stately home. At the door, he’s greeted by a “peering and trembling” schoolmaster and a quarrelsome cook; their demeanor suggests that all is not well within the house.

Jack is taken in to see the master, who offers him money for the medal, then, refused, leads him by candlelight to an open door:

“Am I to go in there with you, sir?”

“Are you afraid to go into a room?”

By that point, yes, Jack is afraid, and so are we. What he finds there — and Fitzgerald’s refusal to strip the discovery of the mixture of eeriness, terror, and pity that it holds for the boy — is wholly plausible, yet as wrenchingly unsettling as any horror out of Lovecraft.

Levi Stahl is the promotions director at the University of Chicago Press and, with Ed Park, co-librarian of the Invisible Library. He blogs at I’ve Been Reading Lately and @levistahl

*****

Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Bottle Imp” (1891)

Selected by Jenny Davidson

As a child, I loved reading scary stories: it was movies that scared me in a bad way. When you’re that young, you can’t even tell what is and isn’t supposed to be scary. I saw Star Wars the year it came out, for instance, when I was about six, and the trash compactor scene (in adulthood purely comic) gave me nightmares for years. And as a teenager, whenever my brothers and I watched The Shining, I would cover up my ears and they would tease me by trying to tear my hands off them — it is the soundtracks that make TV and movies scary, I had already realized, and restricting oneself to the visuals stopped the heart rate from racing.

As a child, I loved reading scary stories: it was movies that scared me in a bad way. When you’re that young, you can’t even tell what is and isn’t supposed to be scary. I saw Star Wars the year it came out, for instance, when I was about six, and the trash compactor scene (in adulthood purely comic) gave me nightmares for years. And as a teenager, whenever my brothers and I watched The Shining, I would cover up my ears and they would tease me by trying to tear my hands off them — it is the soundtracks that make TV and movies scary, I had already realized, and restricting oneself to the visuals stopped the heart rate from racing.

I always had lots of anthologies of tales of the uncanny lying around — people gave them to me as Christmas presents, perhaps. (And again, with the eyes of adulthood, there is money to be made off cheaply printed anthologies of out-of-copyright tales!) Joan Aiken wrote some wonderfully scary stories as well as the more magically homely ones recently reissued as The Serial Garden by Small Beer Press. Poe’s stories got to me, too: “The Black Cat”!

One story that I read again and again, to torment myself with the shiver of near escape, was Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Bottle Imp.” A man buys a bottle that can grant him all he desires — but the fortune he asks for comes to him by way only of the death of a beloved uncle, and he follows the rules explained by the person who sold it to him and sells it to another for a price less than he bought it for (if you die with it in your possession, you’re cursed forever). The bottle comes back to him, though, and if you’ve bought it for two cents, who’s going to be stupid enough to buy it for one cent? You can go to a different country whose currency is lower-denomination, of course — and then there’s the leprosy . . .

“The Bottle Imp” was perfectly calculated to arouse all my anxieties and desires as a child: it still seems to me a cautionary tale whose happy ending doesn’t stop it from leaving one with a chill.

Jenny Davidson teaches at Columbia and blogs at Light Reading.