Reviewed:

Reviewed:

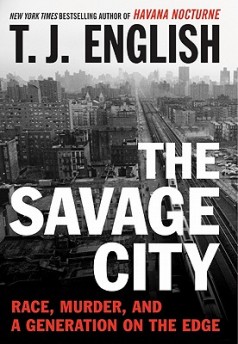

The Savage City by T. J. English

William Morrow, 496 pp., $27.99

When cooking stuffed peppers, the goal is to fill them with varied ingredients but make sure they retain their shape. Bearing this in mind, consider The Savage City — an overstuffed pepper with ingredients spilling out every which way and only a vague idea as to how they once integrated or what final result was envisioned. This vague idea is due mostly to the introduction by T.J. English, offered as a limp schematic for reading this frenetic collection of gruesome details buttressed by historical fact.

The Savage City purports to be a meaty look into “the ten-year period when New York City began its now-legendary descent into mayhem.” English makes enough references to the city and its clamor, grit, and kinetic energy, but the book unfolds in a stultifying pastiche of noir clichés and an oversimplified consideration of race relations. The book opens by declaring, “The streets of New York City are saturated with blood.” It’s best to take a minute after reading this sentence to prepare yourself for the remaining 400-plus pages, which unfold with sanguinary relish and feature prose that walks the fine line between vivid and purple. Lines like, “If headlines could scream, the following day’s papers would have contracted laryngitis,” are regrettably commonplace.

Surely, one of New York’s most violent periods could be discussed and analyzed without the lurid undercurrent that runs from page to page here. Analysis is largely missing from English’s narrative. His writing is less journalistic or investigative in tone than almost fictive. His prose is excessively reliant on symbolism, metaphor, and other descriptive tools of fiction. The seamless fusing of crime and novelistic tendencies best applied by Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood is just distracting here. English’s prose is, to put it a way he might appreciate, dead on arrival. The book’s copious notes might have been more useful integrated with the main text, adding a factual authority about which the reader is left to guess.

English presents three biographical narratives that bear a merely circumstantial relation to one another. The book starts with Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech, those who left Manhattan to attend the speech, and a grisly double murder that took place on that same day in August 1963. As the speech is delivered, George Whitmore, Jr., “ a near-blind, destitute, nineteen-year-old black youth” watches it on television while working at a job in Wildwood, New Jersey. Nearly nine months later, Whitmore would be sleeping under stairwells in Brooklyn and, through a series of convoluted happenings, forced to falsely confess to the double homicide and two sexual assaults. In a police station nearby, Detective Bill Phillips, a “brazenly crooked NYPD officer,” is working a regular job and earning hundreds of dollars in kickbacks from the drug and prostitution businesses. Phillips is a second-generation cop with an unrivaled racist streak. In a disturbingly cyclical revelation, the book ends with Phillips having to face the justice system in an unexpected way. Somewhere between these two extremes is Dhoruba bin Wahad, an early member of New York’s Black Panther Party and a man whose “militant activism” makes him the poster boy for the civil violence that becomes unfairly representative of African-Americans in the eyes of the police.

This propels the book, a catalog of civic violence sometimes relayed from the perspective of the police and often by the minority populations fighting against them. As the book halts forward — occasionally stopping short or reversing — the reader becomes desensitized as English continues to visit courtroom after courtroom, corruption after corruption, and crime after crime without much differentiation or analysis.

On the subject of cities, English makes reference to Mayor Bloomberg’s proclamation that New York is the “safest big city in America.” He takes umbrage that the “claim is made without irony, as if the previous fifty years of the city’s existence were nothing more than a bad dream.” It evidently comes as a shock to English that a city could encounter racial violence, a depressed economy, and political corruption, only to get past it. But that’s what cities do. They move on, they shift, they rebuild. New York isn’t the only city to have come out on the far side of catastrophe. Chicago lived through Mrs. O’Leary’s allegedly clumsy cow, San Francisco rose from the rubble of its earthquake, Pittsburgh is no longer the steel capital. English concludes the book with a reminder: “Today, the city projects an image of security. But the fault lines remain.” These must be similar to those that run underneath his shaky book.

Joshua Zajdman holds a B.A. in English, an M.A. in Literary and Cultural Studies, and a book at all times.

Mentioned in this review: