Reviewed:

Reviewed:

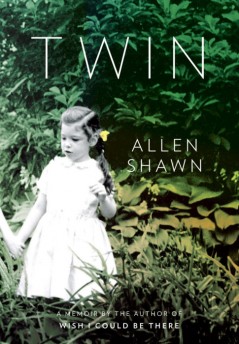

Twin: A Memoir by Allen Shawn

Viking, 240 pp., $25.95

“I did not often think of myself as a twin,” composer Allen Shawn writes in this memoir about his sister, Mary, whose lifelong emotional difficulties would eventually be diagnosed as autism. At eight years old, Mary was sent to a residential center and school in Massachusetts, and never returned home to New York City. “[I]t rarely dawned on me that my singular experience was really a contrapuntal one, and that only when I confronted the sense of loss and the duality at the heart of my life would I begin to achieve some semblance of wholeness — or at least what Freud might have called ‘normal loneliness.’”

Shawn never says so, but any mention of Freud in this context is weighted. The founder of psychoanalysis spent so much time exploring the underground tunnels of the subconscious that he missed what was right in front of him — namely, nine siblings, including two from his father’s previous marriage. As Jeanne Safer writes in her book The Normal One, about the psychological effects of having a mentally ill or physically disabled brother or sister: “‘Siblings’ does not appear in the 404-page index to the twenty-three-volume Standard Edition of Freud — there are a mere five citations for ‘brothers and sisters.’”

Shawn previously wrote about his fragile psychology, including a severe case of agoraphobia, in the memoir Wish I Could Be There, which led him to more deeply consider Mary’s role — both his twinship with her and the family’s handling of her existence — in his own development.

An evaluation of Mary and her parents when she was being interviewed at Briarcliff, the institution where she would spend her adult life, yielded this succinct gem, which should give pause to anyone who invests too much in the glamour of literary reputation: “Father is a rather short, very anxious man, who is editor of the New Yorker magazine.” That would be William Shawn, whose long and illustrious reign at the magazine began in 1952, when Allen and Mary were four. (Allen’s older brother is Wallace Shawn, playwright, actor, and famous serial crier of “Inconceivable!” in The Princess Bride.) It wasn’t just William who appeared on edge. The same report continued: “the two parents seem to be exceptionally anxious people.”

Allen would be even more exceptional in this regard. At 22, he flew to France, only to find, once there, that the “awesome vastness” of the Atlantic seemed like an insurmountable obstacle to returning home. “I felt like a six-year-old who has confidently climbed up a tree and suddenly realizes that he cannot climb down.”

In the face of his hypersensitivity, Shawn always felt his brief times with Mary as a balm. He could have gone into more illuminating detail about the feeling in Twin, but he writes that, “Even now I am more relaxed in her company than at any other time.” He was not encouraged as a youngster to be in her company for long. When he wanted to live near Mary’s residence for a summer as a teenager, he was told by his parents that it wasn’t a good idea; that his sister shouldn’t become overly attached to him.

“[O]ur family had managed to make a near religion of denial,” Shawn writes. “As my brother points out today, our mother’s belief almost seemed to be that it is not a heart attack that kills you, but rather acknowledging that you have had a heart attack.”

That description is gently mocking, but Shawn doesn’t explicitly connect the idea, at that moment in the book, to his own denial of his sister’s experience, and the possible deep psychological effect it has had on him. There is something funny about the mindset that thinks acknowledgment is more devastating than incident, but there is a kernel of truth in it — particularly when it comes to the many incidents more subtle than a heart attack. Shawn now understands his sister’s life as a meaningful lacuna in his own, but full understanding and acknowledgment of the direct ways in which his genetic connection to Mary (and his physical absence from her) might have shaped his own life might always elude him.

As an adult, Shawn and his brother acknowledged to their mother that they knew about their father’s long-running affair with New Yorker writer Lillian Ross. (Ross goes unnamed in the book. Shawn’s mother had accepted the affair as part of her marriage). Soon after her sons told her this, she had a bad attack of colitis, like “a delayed cry of pain.” Denial had given way to disclosure, and emotional reckoning to physical suffering.

Twin is a slim book about an immense subject. Early on, it quickly surveys the history of autism, including the role of Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler, who first used the term. But mostly it’s a gentle look back at a family that could have engendered more resentment than it seems to have. If Shawn still suffers from some denial, it’s the decorous kind that benefits a writer, keeping his tone from becoming hysterical or solipsistic. Shawn’s reminiscence could just as easily have been a long essay in his father’s magazine. At its best, his prose share’s the magazine’s brand of elegant plainspokenness, as in this passage, where he describes the moment he and Mary arrived:

We are six weeks premature. Our mother had lost two babies in previous pregnancies, one a few years before, and the other a few years after my brother’s birth. She is ecstatic. Our father is home with a cold. He and our five-year-old brother receive the news of the twin births over the phone — “Twins! A boy and a girl!” Twins were usually a surprise in those days, and they are astonished. We are tiny by ancestry, by being twins, and by being born so early. We weigh four pounds each. We are put in incubators and stay there for six weeks. After all these many days in the hospital we are home. Our father, who had once thought that the world was too difficult a place to bring more people into it, but who after eighteen years of marriage had finally changed his mind, is now lifting us over his head in joy and amazement. Our brother, dressed in a white short-sleeved shirt and corduroy dungarees, is posing for pictures holding the two of us, one in each arm.

In a dismissive review, Neil Genzlinger wrote, “Shawn describes how the family would arrive in a limousine for their occasional visits with Mary, an image that will infuriate those who have not had the luxury of paying someone else to make their problems go away.” But one cannot pay to make a problem like this go away, only to repress it, and having his sister leave home was more traumatic to a little boy than almost any other solution might have been.

“[T]he exact nature of each person’s ordering of life is unique, and the origins of it generally remain an unsolved puzzle,” Shawn says. He doesn’t solve the puzzle of his family’s “strange private agendas,” or the puzzle of himself, but he considers them with a graceful intelligence, and no variety of coping with life’s anxiety and tragedy — even by those who ride in limousines — should be considered inherently beneath our interest.

John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.

Mentioned in this review:

Twin: A Memoir

Wish I Could Be There: Notes from a Phobic Life

The Normal One: Life with a Difficult or Damaged Sibling