Reviewed:

Reviewed:

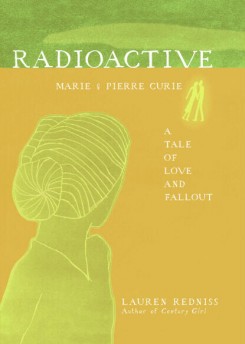

Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie: A Tale of Love and Fallout by Lauren Redniss

It Books, 208 pp., $29.99

The death of Pierre Curie, knocked down in the fog on a busy Paris street and passed over by a horse-drawn cart, was not the lead story in French newspapers the next day. The death of the Nobel Prize-winning scientist who had worked with his wife, Marie Curie, to isolate and filter out a visible portion of the newly discovered element radium, shared the headlines with a story that had just made its way overseas: the devastation of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake.

“Catastrophism, a geological theory championed by zoologist Cuvier, holds that time lurches forward in sudden disasters. In Paris there is a street named after Cuvier. It rolls downhill toward the Seine alongside a garden. On the rue Cuvier, May 15th 1858, Pierre Curie was born.”

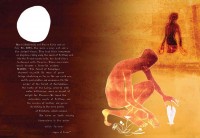

So begins Radioactive by author and artist Lauren Redniss, with the first of the many perfect curlicues of feeling and fact that cycle through the work. Redniss’ books defy category: graphic works of nonfiction that blend illustration, object, fact, and fantasy. Her first book, Century Girl, was a scrapbook of sorts for the last living Ziegfield Girl, Doris Eaton Travis, who died just last year at the age of 106. The surface of the page was pieced together in Century Girl, with ticket stubs, playbills, and photographs mingling with drawings of chorus girls and proper cha-cha technique. In Radioactive, the surface bleeds, colors crash into the handwritten text, Pierre and Marie Curie floating through it all like lovers in a Chagall painting. The story and the cyanotype printing technique used by Redniss are subtle mirrors of each other. Black on white gives way to an x-ray of white on black, then white on blue, then on orange and yellow and greens, each according to the protagonist’s mood, which swings from triumph to grief.

The words of Marie’s mourning journal are faint gray on black: “Yesterday I gave the first class replacing my Pierre. What grief and what despair! You would have been happy to see me as a professor at the Sorbonne, and I myself would have so willingly done it for you — But to do it in your place, my Pierre, could one dream of a thing more cruel . . . I don’t feel at all lively any more nor young, I no longer know what joy is or even pleasure. Tomorrow I will be 39 . . . I probably have only a little time to realize at least a part of the work I have begun.” I had to hold the book up to my nose to read it correctly, a little embarrassed to peer so closely at the agony of a brilliant woman.

The story begins quietly with black-and-white line drawings and straightforward biographies of Pierre and Marie, each confined to their own page until they meet and their world explodes into color. Their work and discoveries are the heart of the story, and after Pierre dies, Marie’s life continues the thread of the plot — her nursing of the wounded in World War I, her happiness and despair in future romances. But just as Pierre was not Marie’s only love, the two scientists are not the book’s only characters. Each new discovery by Marie sends Redniss off on a new tangent: chemotherapy saving the life of a young boy in 2001, the brightly colored birds borne out of Chernobyl, the radiation effecting a survivor of the atomic bomb. When we leave Marie’s side it takes a grinding of gears to return there again.

The story begins quietly with black-and-white line drawings and straightforward biographies of Pierre and Marie, each confined to their own page until they meet and their world explodes into color. Their work and discoveries are the heart of the story, and after Pierre dies, Marie’s life continues the thread of the plot — her nursing of the wounded in World War I, her happiness and despair in future romances. But just as Pierre was not Marie’s only love, the two scientists are not the book’s only characters. Each new discovery by Marie sends Redniss off on a new tangent: chemotherapy saving the life of a young boy in 2001, the brightly colored birds borne out of Chernobyl, the radiation effecting a survivor of the atomic bomb. When we leave Marie’s side it takes a grinding of gears to return there again.

Maybe Redniss has invented a new form with her work — the graphic nonfiction epic — but more likely she’s just readjusted our reading energies. I had a similar experience with a book so huge that it defied ever being finished: the centuries-jumping epic by Chris Ware, Jimmy Corrigan: Smartest Kid on Earth. Time is fractured in the comic book window, it slows and circles and speeds and stops. When I read books like these, I feel like I’m opening up a thousand little boxes at once, reading up and down and across and back, until I catch myself daydreaming about the whole experience. At one point, I stared at a single page of Radioactive until my coffee turned cold.

Redniss spends her time linking the life and loves of Marie Curie with the vast scope of her work, after she has Marie seemingly close the door on any speculation in the book’s epigraph: “There is no connection between my scientific work and the facts of my private life.” Instead of negating what follows, the epigraph somehow frees us to enjoy the experience, in which Marie’s personal life and scientific discoveries never connect but race in infinite parallels, unrestrained by discovery or death.

Michelle Legro is an assistant editor at Lapham’s Quarterly and the web editor of laphamsquarterly.org.

Mentioned in this review:

Radioactive

Century Girl

Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth