Reviewed:

Reviewed:

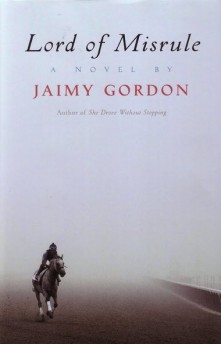

Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon

McPherson & Company, 296 pp., $25.00

For the ever-diminishing slice of us in the culture’s Venn diagram who love both horse racing and literature, it’s easy to greet Lord of Misrule as a gift, not to be looked in the mouth. Jaimy Gordon finds plenty of human frailty and ugliness at the track, but she also sees poetry and philosophy, supporting a tradition that needs all the help it can get. Her novel, published by tiny McPherson & Company, may sport some off-putting idiosyncrasies that make its unlikely win of the National Book Award even more unlikely, but anyone who cares for the milieu can’t miss it.

The book, loosely organized around four races and the connections of several wanna-but-never-will-be horses at fictional Indian Mound Downs in West Virginia, is told from the alternating perspectives of its characters. Most of the chapters are in third person, though a few, distractingly, are in second. The central figures are Medicine Ed, a 72-year-old African-American groom who’s been in the business since he was eight, and Maggie, a former small-town food writer now working with her boyfriend Tommy Hansel, an owner who abruptly arrives at Indian Mound with a handful of horses. Tommy figures Indian Mound for the only place where his animals are almost sure things, and he plans to steal a few races before anyone catches on.

One suspects long before the book turns for home that plot is not paramount. Lord of Misrule is impressionistic and episodic. Its tough-luck characters barely have the wherewithal to learn each other’s names (to Medicine Ed, Maggie is always “the frizzly hair girl”), much less act with enough resolve to make a story. When they do rouse themselves for a finale, things get frantic, even a bit silly, with intentional druggings and gunplay and the feel of an unconvincing Carl Hiaasen imitation tacked on to a series of character studies.

Aside from a brief prefatory excerpt from Ainslie’s Complete Guide to Thoroughbred Racing to explain the nature of claiming races (races in which the horses entered can be purchased before running for a set price), Gordon proceeds with the welcome assumption that her audience knows its way around the track, or can learn the basics elsewhere. About an apprentice jockey, she writes, “you know how they say about a bugboy, he save you seven pounds in the gate and add thirty pounds in the stretch.”

But it’s all native English speakers, not just racing novices, who will have occasional problems understanding Gordon. She’s certainly capable of precise insight. She writes about Maggie, as she tends to a horse named Pelter:

For all her stamina, as a human girl she knew she was lazy and unambitious, except for this one thing: She could find her way to the boundary where she ended and some other strain of living creature began. On the last little spit of being human, staring through rags of fog into the not human, where you weren’t supposed to be able to see let alone cross, she could make a kind of home.

That’s beautifully rendered, but trouble comes when Gordon tries to make her home on that little spit as well. She has a pseudo-mystical approach to people as well as horses, and can sometimes veer toward the New Age. She’s also not afraid of disorienting the reader or indulging herself, jumping into loosely directed dialogue midstream (and like Cormac McCarthy, she doesn’t believe in quotation marks); formally situating characters several pages after they’ve first appeared, if ever; peppering Medicine Ed’s sections with hokey African-American dialect; and generally following her muse down whatever rabbit hole it decides to dive. (She’s particularly kooky when she writes about the borderline-S&M relationship between Maggie and Tommy, and a few passages from the novel could be nominated for the next Bad Sex in Fiction Award.) The book from the last decade that Lord of Misrule most recalled for me was Christine Schutt’s Florida, another obscure finalist for the National Book Award (in 2004) that strenuously stuck to its own poetic rhythms. This path can have its cost. Orwell’s belief that “good prose is like a windowpane” shouldn’t be a tyrannical rule, but it’s also rarely edifying to study a muddy windshield.

Lord of Misrule isn’t a chore. It’s more accurate to say that it alternately charms and befuddles. It’s possible to move from deep admiration to deep suspicion of it in the space between paragraphs. It’s wise and flaky. It’s funny intentionally and unintentionally. It begins with a bit of overworked imagery and ends with a great plainspoken sentence.

It’s possible there are readers who will appreciate equally both of Gordon’s modes, but I’d make it 10-1, at best. So though it’s a pointless notion, I hope the NBA committee wasn’t rewarding the book’s flightier flourishes, but its clearer (still stylish) eyes, the ones that alight on a world rarely addressed in fiction, as in this scene when the horses take to the track before the book’s biggest race:

Who recalls that six years ago Sudanese ran in the Gold Bug Futurity for $200,000, led to the sixteenth pole and held on to show? Certainly not he. Next come Wolgamot, Island Life and Hung The Moon, all mainstays of the 2000-dollar allowance field, la crème de la crud of Indian Mound Downs, track favorites, each with his loyal following, all routers, all grizzled regulars of the ninth and tenth race, named on many an exacta ticket, each dragging his day of glory behind him, some Farmers and Merchants Cup or Pickle Packers Association Handicap or even some just-missed minor stakes. All are reasonably clean for this race, scarred and gleaming dark bays of various shades and descriptions — the commonest run of racehorse, dirt cheap, bone sore and all more beautiful than chests of viols of inlaid rosewood and pear. Hung The Moon, an amiable gelding of ten years old, stops to snatch at a dusty tuft of crabgrass along the parking lot fence. If this race is anything special he hasn’t noticed.

Passages like that are award-worthy, and reason enough to hope that Gordon isn’t done writing about the ponies and those who play them.

John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.

Mentioned in this review: