Reviewed:

Reviewed:

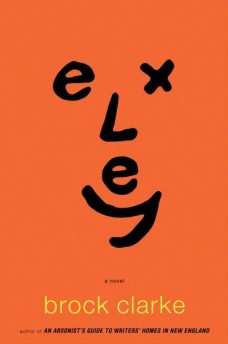

Exley by Brock Clarke

Algonquin, 320 pp., $24.95

At first blush, Exley, Brock Clarke’s follow-up to his much-acclaimed An Arsonist’s Guide to Writers’ Homes in New England, seems afflicted by some very grave difficulties. The novel’s two narrators, both unreliable in the extreme, are prone to half-whimsical, half-intense narration, and their highly mannered voices exhibit an almost-unbearable preciousness. One is a nine-year-old boy, a prodigiously fast reader who has been advanced to the eighth grade, and the other is a “mental health professional,” to use his own preferred parlance.

The boy is Miller Le Ray, and, initially anyway, he is believable only as plot device. Miller, who is still in possession of his milk teeth, has the ability to read a book cover to cover in no time at all, but this ability is mostly meaningful as a counterpoint to his inability to read his own situation. His father, to whom he is endlessly devoted, has taken off, leaving with the sadly resigned, perhaps sardonic, “Maybe I should go to Iraq, too.” Miller takes his father’s words at face value, convinced that his dad is at war despite his mother’s repeated insistence that this is not the case, and it is this commitment to the idea that brings Miller to a psychiatrist, who is primarily interested in the boy’s mother.

The novel’s action begins when Miller, waking to the sounds of his mother crying in the bathroom, becomes certain that his dad has returned from Iraq and is now at the VA Hospital. Following through on his hunch, Miller finds his father, apparently badly hurt, at the hospital (although the man’s identity is not definitively substantiated until the end of the novel). Delighted to have his dad back and terrified at his critical condition, Miller decides that the only way to save his family is to locate Frederick Exley, the author of his dad’s favorite book, A Fan’s Notes. In Miller’s magical thinking, bringing Exley to his father’s bedside will restore his dad to health and bring him home. In the meantime, Miller’s mother has prevailed on his doctor to serve as a detective of sorts, to follow Miller and sort out the truth of his activities from his imaginative recreations of events. But Sherlock Holmes the doctor is not, and his attempts to spy on his young patient turn increasingly comical, even as the stakes of Miller’s quest grow ever higher.

What Miller believes, what he actually knows, and what is ultimately true converge and diverge, a shifting ground of tangled familial relationships, old resentments and suspicions, and impossible fantasies of happiness. He knows too much and too little, caught up in the demands of a world that refuses to take its time, to allow him to slowly shed his innocence. Forced to grow up, Miller takes refuge in fantasy, struggling to maintain a sense of order and control.

But this, Exley suggests, is not simply a child’s predicament. In a time of war, the breakdown of the nuclear family, the many boundless disappointments that define American life in the 21st century, we all harbor illusions and fight to protect them. There is, finally, a grace and dignity in the attempt to believe otherwise, to hold out hope, to hold on to faith. Like A Fan’s Notes, Exley’s “fictionalized memoir,” which Exley lovingly parodies and borrows from, Clarke’s novel suggests that it is in our fantasies that we are most truly alive, and how we fight for what we want to believe defines our best selves.

Exley sometimes strains under the burden of the voices it assigns to its narrators. Miller, who is prone to imitating his father’s speech patterns, inspired by Exley’s book, is fond of pronouncements like this one: “Because this is one of the things I learned on my own: you need to say things simply, especially when they are complicated.” When he makes such declarations—which is rather often—the line between youthful precociousness and unbelievable maturity becomes unfortunately thin. Meanwhile, Miller’s doctor—dubbed “Horatio Pahnee” by his young patient—appears to be using his professional “Notes” on treatment as a diary filled with inappropriate confessions, his observations frequently assuming the following pattern: “memorized and, indeed, committed to memory” or “most unusual, and, indeed, most unique.” Although each narrator remarks on the other’s stylistic tendencies, this gesture of awareness does not redeem their verbal tics, which are grating, and grow ever more so.

Still, Exley is a book worth sticking with, in part because its twists and turns are genuinely surprising, but also because its insight (and, indeed, its insistence), in the words of Dr. Pahnee, that “we don’t know what’s going to kill us—whether it’ll be a kiss, a bottle, a book, a bomb—which is why we keep trusting people who say they can save us, whether it’s a writer, a father, a mother, a lawyer, a son, a soldier, a lover, or a mental health professional,” reveals the generous, tender heart quietly beating beneath the novel’s surface.

Yevgeniya Traps is a doctoral candidate in English at the Graduate Center-CUNY.