Reviewed:

Reviewed:

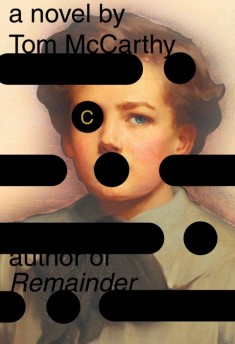

C by Tom McCarthy

Knopf, 320 pp., $25.95

The descriptions of Versoie House, the fictional estate of the Carrefax family and the primary setting of Tom McCarthy’s new novel, C, are quietly unlike those of any other late-Victorian idyll. Versoie seems, at first, to offer a familiar kind of pastoral splendor—birds glide above the property, its orchard boasts rich hues of white and red, the air is still, the conifers are full-grown—but the grounds are at once unusually silent (“silent as a tomb,” one visitor remarks) and humming. This sonic unease quickly clarifies itself: The patriarch of the estate, Simeon Carrefax, runs a school for deaf children while simultaneously conducting experiments with wireless technology. (An early competitor of Marconi’s, Simeon jealously attributes his rival’s ultimate achievement to his framework of institutional support.)

Versoie’s perennial hush only casts “the fricative rasp of copper wire against copper wire” into relief, and this electric ambience forms something like a viscous liquid through which the trees swim. This liquid floods C, defining and intruding upon lives that, in other novels, would be individuated and romantic but are here interrupted, made strange. People’s bodies in C belong to a larger network of signals, a melee of telegraphic dispatches that require as many conductive units as possible.

Serge’s turn-of-the-century childhood at Versoie floats between his family’s binary theories of communication. His father has a distaste for encryption, and demands that his deaf students fill the air with as much crisp, intelligible speech as they can. (Signing and muteness are prohibited.) Serge’s older sister, Sophie, however, is all code and secrecy: She is clandestine in her love life, she commands a Latinate taxonomy of insects that few others understand, and she is a virtuosic amateur code-cracker. Though Sophie’s love of code runs defiantly counter to her father’s promotion of transparency, their different modes arise from the same fact about bodies, a fact of which Serge is only half-aware: Bodies are conduits for all sorts of signals and products. Simeon views speech itself as a “product” to be wrested from the deaf children’s latent machinery, and the children appear disturbingly ventriloquized during their recitations of verse. Likewise, Sophie’s tacit confession of her pregnancy could double as an admission of her own conductivity: “She takes his hand and lays it on her stomach. Her skin, through the cotton of her thin white dress, is soft and pliant. Serge can feel a rumbling beneath it.”

The young Serge is a precocious “radio bug,” monitoring all of the bland, prewar transmissions he can receive through his homemade telegraphy console. The messages he transcribes are terse and uninteresting, but the very fact of their transmission inspires vivid imaginings of their provenance. McCarthy saddles Serge with a loaded lack of perspective—he’s a meticulous observer of signals, but can’t crack codes, or even tease out larger narratives from disparate facts. This lack of perspective keeps him from fully understanding what it means when his sister has taken a lover or when she takes her own life.

Sophie’s death sets off the string of fortuities that carry Serge through the rest of the novel. Traumatized, melancholic, and constipated, Serge is taken by a teacher to Klodêbrady, a fictional spa town near Dresden that is in many ways reminiscent of Thomas Mann’s nonfictional Davos. There, Serge is treated for black bile and gauzy vision, afflictions as anachronistic as the hydrotherapeutic treatment he receives for them. Serge then enrolls in the School of Military Aeronautics, leading directly to a stint as an airborne observer in an Allied squadron during World War I. These are among the novel’s most fascinating passages and, because of their unwillingness to register the emotional impact of THE squadron’s decimation, among its most disturbing. Serge is undeterred, even excited, by attritional violence en masse, although he’s most comfortable when viewing it from high-altitude vantages, with the alienating distance turning soldiers and complex terrain into insects and a delirious aggregation of geometric forms.

One day after Serge has returned from airborne combat with German trench soldiers, the recording officer requests a “narrative” from him. Serge responds, “We went up; we saw stuff; it was good.” Serge imparts the basic facts and feelings, but he is highly cognizant of the fact that his perception of these facts and feelings matters very little. In this way, Serge has both more and less character than conventional novelistic subjects—he is a conductor of history, flush with it, and his consciousness is so subordinated to this role that to take charge of the narrative would make no sense.

Reading C against the backdrop of Tom McCarthy’s popular debut novel, Remainder, one develops a keen sense of the limited self-awareness McCarthy enjoys planting within his characters. When nearing the finale of Remainder, I felt suffocated (in a delightful way) by the unreflective “I” of the narrator. Serge is similarly unreflective, and like the narrator of Remainder, he is subject to unexamined washes of good feeling. But where Remainder humored the narrator’s hubristic expressions of agency, C gives Serge little agency to express and even littler inclination to express it.

Serge survives the war, albeit passively. He spends some drugged-out time in the modernist epicenter of postwar Bloomsbury before being whisked away to Egypt for C’s coda. Traveling under the auspices of the Imperial Communications Committee, Serge investigates “acts of telecommunicative blasphemy” that have been occurring in the farthest reaches of the Empire. Despite Egypt’s early-20th-century hostility to modern communications technology, these are the chapters of the novel in which Marconi’s legacy is most prominent, and in which static seems to saturate the atmosphere most intensely. McCarthy’s proposal of “a static that contains all messages ever sent” begs to be compared with Remainder, which framed history as little more than accreted gunk. Here, history is an immaterial environment, and Serge its patch bay, prepared to facilitate the creation of full circuits. His regular and inopportune erections throughout the novel suggest his function as a lightning rod for seminal events.

Though it may seem implausible that a 19th-century-born youth could become so subsumed by the contemporary technology, this aspect of the book only flatters McCarthy’s intelligent involvement with our present moment. Rather than overdrawing a correlation between the technologies that bookend the last century, McCarthy situates Marconi’s wireless breakthroughs within a less discussed but still timeless set of urges: to collapse space, to become merely functionaries, to belong to an interrupted, polyglot, and adulterated community. Our current immersion in something very much like C’s unbounded field of static, then, is not something so novel, but rather just one installment in an ongoing immanent project.

Daniel Pearce is a writer living in New York.