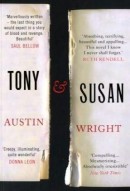

From the UK’s Telegraph, the kind of story The Second Pass likes to see: An editor named Ravi Mirchandani is reissuing a novel called Tony and Susan by Austin Wright. (Via Bookslut)

From the UK’s Telegraph, the kind of story The Second Pass likes to see: An editor named Ravi Mirchandani is reissuing a novel called Tony and Susan by Austin Wright. (Via Bookslut)

For the past 17 years, Mirchandani has bought (increasingly hard to come by) copies of the book as gifts for friends: “They’d all love it too,” he tells me, “and they’d say: Who is this man?”

The man was Austin Wright, an American novelist and English professor who died in 2003 at the age of 80. Despite having been praised by the likes of Saul Bellow, he remained little known in his lifetime. Yet the handsomely packaged – and rapturously reviewed – reissue of Tony and Susan, his fourth novel, is set to offer Wright’s ghost something approaching fame.

The Telegraph also has an excerpt from the novel. More from the profile of Wright:

Between 1969 and 1977, Wright wrote three experimental novels – Camden’s Eyes, First Persons and The Morley Mythology – all of which played with ideas about fiction and narrative voice. The protagonists wake up to discover they are characters in novels, or hear voices in their head so fully fledged they have real names. There are books within books and minds within minds. . . . At the time, such self-conscious writing was more or less part of the mainstream in the U.S. – John Barth was all the rage; Donald Barthelme’s stories were published in the New Yorker; it was not uncommon for fiction to wear its underwear over its clothes, so to speak. . . .

For 23 years, Wright taught English at the University of Cincinnati. He published several works of straight literary criticism and then, in 1990, a fantastically zany interpretation of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, seen through the eyes of professors and students of Wright’s own invention.

If his interests in fiction and criticism began to come together in that strangely personal tome, Tony and Susan took the fusion to another level. It was published the year Wright retired from his professorial post, and a good couple of decades after the zenith of his earlier brand of narrative exercise. Freed from fashion, perhaps, yet wedded to his own sense of play, he produced a highly commercial, fast-paced thriller that also manages to be a meditation on everything writing meant to him. As its dual effect unfolds, you can’t quite believe the triumph.