Introduction

When I launched this site a year ago today, one of my main goals was to approach reading the way that readers do, not necessarily the way that publishers and even many other reviews do. Publishers naturally want to tell you about what’s new or what’s evergreen. But most readers know the pleasure of somehow discovering and falling in love with a book that has fallen from view. And no status is farther from view than the dreaded “out of print.” I’ve learned from my years reading that countless terrific books have met this fate, and the Backlist section of this site is meant, in part, to shine light on just a few of them. I thought it would be appropriate to mark the first anniversary of The Second Pass by asking voracious readers to recommend their favorite out-of-print book. Their answers follow. I hope you enjoy them as much as I did. —JW

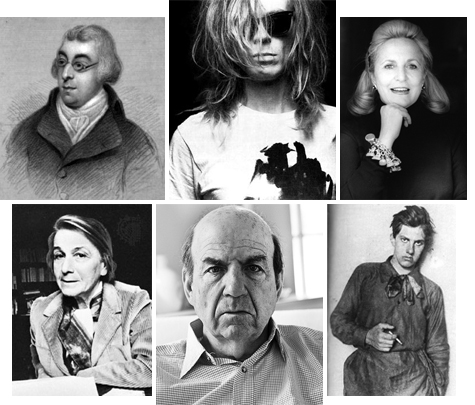

The Disenchanted by Budd Schulberg (1950)

Budd Schulberg, who died last year at the age of 95, is best known for two works, the Oscar-winning screenplay for On The Waterfront and the satiric Hollywood novel What Makes Sammy Run? The latter is frequently mentioned when literary folks discuss candidates for The Great Hollywood Novel, But it’s possible that What Makes Sammy Run? isn’t even Schulberg’s main contender for the title. There are those—Anthony Burgess, for one—who would argue that The Disenchanted is not only a superior book, but that it represents the author’s best stab at literary immortality. “I have read it once every two years, perhaps even oftener,” Burgess wrote of The Disenchanted, naming it one of his hundred greatest novels of the 20th century. “This makes a total of about sixteen re-readings, and there are few other novels of which I can say this.”

Budd Schulberg, who died last year at the age of 95, is best known for two works, the Oscar-winning screenplay for On The Waterfront and the satiric Hollywood novel What Makes Sammy Run? The latter is frequently mentioned when literary folks discuss candidates for The Great Hollywood Novel, But it’s possible that What Makes Sammy Run? isn’t even Schulberg’s main contender for the title. There are those—Anthony Burgess, for one—who would argue that The Disenchanted is not only a superior book, but that it represents the author’s best stab at literary immortality. “I have read it once every two years, perhaps even oftener,” Burgess wrote of The Disenchanted, naming it one of his hundred greatest novels of the 20th century. “This makes a total of about sixteen re-readings, and there are few other novels of which I can say this.”

Schulberg came from Hollywood stock—he was the son of Paramount Studios chief B. P. Schulberg—and The Disenchanted is loosely based on a disastrous early screenwriting assignment thrust upon him: he was instructed to accompany a once famous but now washed-up writer on a research trip to Dartmouth College. The writer’s name was F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the booze-soaked trip to Dartmouth all but brought his career in Hollywood to a close.

The Disenchanted portrays a bygone world—the Hollywood Studio System of the ’30s—as seen from the inside by a naive, wide-eyed young screenwriter. At the novel’s center is the author Manley Halliday, a long way from glory and bent on self-destruction. Schulberg’s prose is simple and unadorned throughout, but his imagining of a once renowned artist falling helpless prey to his own weakness manages to elicit genuine pathos without recourse to easy sentimentality—traits that remained consistent throughout his varied career.

—John Davidson

*****

Krautrocksampler by Julian Cope (1995)

In all its partial glory, I nominate Krautrocksampler by Julian Cope, or to give it its full incantatory title, Krautrocksampler: One Head’s Guide to the Great Kosmische Musik—1968 Onwards.

In all its partial glory, I nominate Krautrocksampler by Julian Cope, or to give it its full incantatory title, Krautrocksampler: One Head’s Guide to the Great Kosmische Musik—1968 Onwards.

Cope wrote Krautrocksampler to reclaim and define groups like Can, Neu!, Faust, Amon Düül II etc.—i.e., the ones he liked as a kid—and to suggest that they articulated a progressive vision of what it was to be young and German in the late 1960s and early 1970s—a vision which owed little or nothing to the dominant American and British rock forms of the era. Cope’s teenage enthusiasm for this mysterious, shamanic music is reflected in how he writes about it: LOUD and FAST. It’s an incredible performance: more interview than overview.

You can no longer buy Krautrocksampler in the shops because Cope doesn’t want you to. He self-published the book via his Head Heritage imprint in 1995. Then about five years later he unpublished it. As the author notes in the Krautrock Q&A on his web site, “It’s a period piece written at a time when no fucker was interested and now all these neo-Krautheads are at me saying it’s out of date. Fuck them!”

If you want to read Krautrocksampler in the here and now, there are three avenues open to you. You can buy a secondhand copy from Amazon or eBay at a cost of at least £100. You can learn German or French and pick up a copy in translation (both still in print). Or you can visit a blog like Mixtapes’n’Blurbs or Swan Fungus or Substix and download a PDF for nothing. Or just click here. Or here. And the book will be yours.

Some of these links have been active for several years, suggesting Cope is permitting this particular piece of work to circulate as elektronisches samizdat. Which is why Krautrocksampler is my favorite out-of-print book—the manner of its life and afterlife is as forward-thinking as the book itself and the music for which it proselytizes. As the man says: “Krautrock is about enlightenment, not complete-ism for some bourgeois record-collector to get purist about.”

NOTE: The Head Heritage website contains essays and reviews by Cope on numerous records, artists, and imaginary compilations—Glamrocksampler, Hardrocksampler, Postpunksampler, et al. To pick just one, his love letter to Miles Davis’ electric period will make your heart beat both LOUDER and FASTER.

—Andy Miller

*****

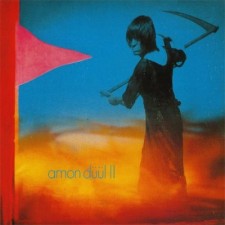

Memoirs of the First Forty-Five Years of the Life of James Lackington (1791)

One of the liveliest memoirs ever written has been in and out of print since its original publication in 1791, often the victim of print-on-demand publishers who produce versions with missing pages and inscrutable fonts. The Memoirs of the First Forty-Five Years of the Life of James Lackington deserves better. A shoemaker’s son who taught himself to read and eventually owned the largest bookstore in England (a multistoried tourist attraction big enough to accommodate a horse-drawn coach), Lackington revolutionized the way books were sold.

Too flamboyant to care about the opinion of rival booksellers, and too swept up in the ideologies of his day (enlightenment, humanitarianism, self-improvement), Lackington invented the remainder in order to rescue unsold books from the scrap heap and make them affordable for the laboring class. He may have been, before anything, a canny businessman who offended the elite with his nouveau-riche flair (Small profits do great things was stenciled on the door of his carriage), but his ideals about universal access to literature were firm, and they superseded any blowhard tendencies he was rumored to possess.

Lackington’s first memoir is an amber-caught distillation of every late-eighteenth-century trope copped from the pages of better writers. One reads it for its earthy humor, and for a peek into an ordinary man’s brain at a time of radical cultural transformation—there was little Lackington the book-lover hadn’t read, and it shows in countless allusions: the words or ideas of Pope, Young, Wesley, Thomson, and every other popular 18th-century thinker make an appearance. Few other documents will give today’s reader such a pleasing crash course on the age. It’s also a must-read—out of gratitude, if nothing else—for anyone who’s ever padded their library with remaindered titles. “You cannot conceive what agreeable sensations I enjoy,” Lackington wrote (looking back on two decades in the trade), “in diffusing through the world, such an immense number of books, by which many have been enlightened and taught to think.” His pride is palpable and his heart in the right place.

—Ranylt Richildis

(Image: Etching of James Lackington’s bookstore, “Temple of the Muses,” by William Wallis after a work by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, 1828.)

*****

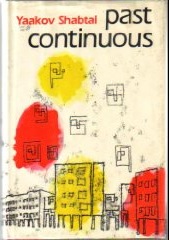

Past Continuous by Yaakov Shabtai (1977)

The Hebrew title of Yaakov Shabtai’s first and only completed novel—a second was pieced together from various drafts after he died at age 47—is Zikhron Devarim, literally Remembrance of Things. Both the literal translation and the anglicized title, Past Continuous, are apt, implying, in the spirit of Faulkner, that the past is never truly past, and, in the spirit of Proust, that the simplest remembrances can be fertile novelistic ground. Few novels are as fecund as Shabtai’s book, a foundational text of contemporary Hebrew literature composed of a single paragraph stretching across nearly 300 pages, with some sentences several pages long.

The Hebrew title of Yaakov Shabtai’s first and only completed novel—a second was pieced together from various drafts after he died at age 47—is Zikhron Devarim, literally Remembrance of Things. Both the literal translation and the anglicized title, Past Continuous, are apt, implying, in the spirit of Faulkner, that the past is never truly past, and, in the spirit of Proust, that the simplest remembrances can be fertile novelistic ground. Few novels are as fecund as Shabtai’s book, a foundational text of contemporary Hebrew literature composed of a single paragraph stretching across nearly 300 pages, with some sentences several pages long.

Past Continuous tells the story of three men, Caesar, Goldman, and Israel, all in their early thirties and terribly lost. Caesar is an inveterate philanderer and a poor father to his two children; Israel, an emotionally vacant pianist, spends most of his time marooned on the couch in Caesar’s photography studio; Goldman, after a brief marriage, has retreated to his parents’ home, where he tries to translate Somnium, Johannes Kepler’s fantastical work about a trip to the moon. We also learn in the first sentence that Goldman will kill himself exactly nine months after his domineering and unwaveringly idealistic father dies.

The story follows these men in their day-to-day wanderings in Tel Aviv, calling on friends and lovers, visiting estranged family members, walking the history-rich but still young streets. Shabtai’s third-person narrative fluently traverses the bottomless connections between past and present. The novel finds multitudes in, for example, the story of an apartment building and the plot of land on which it stands, somehow making disparate times, people, and places coexist in one shimmering sentence.

The book’s stylistic conceit can be daunting and may require the reader to step back and reread some passages. But it is also a style that, as I’ve seen pointed out elsewhere, represents the ultimate union of form and content. The novel is one long, vibrant, almost living paragraph, dashing back and forth through space and time, because that is the only way to faithfully represent the connections that the story produces. These connections are impossible to summarize but, taken together, form a novel that is numinous in its gifts, abounding in linguistic beauty, and uncommonly sad.

—Jacob Silverman

*****

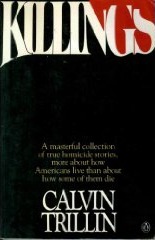

Killings by Calvin Trillin (1984)

It’s easy to take Calvin Trillin for granted. He’s funny, for one thing. And he’s been writing for so long—he’s had a piece in The New Yorker or The Nation more or less every month or two since 1963, and there isn’t much he hasn’t written: memoir, reportage, novels, doggerel. I don’t see how anyone in love or loved can live without his Alice books, especially About Alice

It’s easy to take Calvin Trillin for granted. He’s funny, for one thing. And he’s been writing for so long—he’s had a piece in The New Yorker or The Nation more or less every month or two since 1963, and there isn’t much he hasn’t written: memoir, reportage, novels, doggerel. I don’t see how anyone in love or loved can live without his Alice books, especially About Alice. But his best book—and best proof of the seriousness of his art, his good-heartedness, and the shoe leather he wears out while chasing a story—is out of print and strangely neglected.

Killings was published in 1984 but the sixteen pieces it contains, true stories of homicides all originally published in The New Yorker, were written between 1969 and 1982. Together they form a classic account of American life in the 1970s, as essential a record of that tense time as Joan Didion’s The White Album, Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter, or Big Star’s records. In reviewing the book for the Chicago Sun-Times, the writer Edward Abbey said that “in each of these stories is the basis of a Dostevskian novel.” He wasn’t exaggerating.

In the introduction Trillin declared that “a killing often seemed to represent the best opportunity to write about people one at a time,” and more than anything else the book epitomizes this high and difficult art. The people at the core of its stories—feuding Mexican-American families in Southern California; a visiting filmmaker shot by a property owner in Kentucky; a Hmong family who attempted suicide in Iowa; one of the first female mine workers in Pennsylvania—feel vivid and alive in a way only the best documentary films usually manage.

Like all murder mysteries, the book is suspenseful. But it’s true to the raw, messy drama of the living as well as the dead. “These stories,” wrote Trillin, “are meant to be more about how Americans live than about how some of them die.” He captures that living in part through all the incidental music of American life. He can seem positively drunk on the wonderfully odd names of people, places, businesses. But there’s also a wonderful silence about the book, and a clarity in its storytelling—even when the facts don’t all add up—that lets the simple richness of ordinary American lives endure on the page.

—Matt Weiland

*****

The Curiosities of Literature by Isaac D’Israeli (1791-1823)

Isaac D’Israeli was a man of the library, not much more than “an ethereal presence” in the life of his family, according to Adam Kirsch’s recent biography of his son, novelist and later British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. The D’Israeli family’s loss, however, is our gain: In 1791, D’Israeli published, and, spurred by its success, over the next 30 years continually expanded, The Curiosities of Literature, one of the most unusual and entertaining books in all of English literature, a jam-packed grab bag of, well, exactly what its title describes—if, that is, you expand the definition of literature to include whatever D’Israeli happened across in his library. He collected strange and amusing anecdotes willy-nilly, with neither plan nor purpose beyond a desire to share the distilled fruits of his life of reading. And so we get pieces on bibliomania, errata, the destruction of books, Cicero’s puns, Cervantes, Milton, hell, alchemy, the history of gloves, author portraits, manuscripts, feudal customs, 17th-century usurers, the introduction of coffee, English drinking customs, and much, much more.

Isaac D’Israeli was a man of the library, not much more than “an ethereal presence” in the life of his family, according to Adam Kirsch’s recent biography of his son, novelist and later British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. The D’Israeli family’s loss, however, is our gain: In 1791, D’Israeli published, and, spurred by its success, over the next 30 years continually expanded, The Curiosities of Literature, one of the most unusual and entertaining books in all of English literature, a jam-packed grab bag of, well, exactly what its title describes—if, that is, you expand the definition of literature to include whatever D’Israeli happened across in his library. He collected strange and amusing anecdotes willy-nilly, with neither plan nor purpose beyond a desire to share the distilled fruits of his life of reading. And so we get pieces on bibliomania, errata, the destruction of books, Cicero’s puns, Cervantes, Milton, hell, alchemy, the history of gloves, author portraits, manuscripts, feudal customs, 17th-century usurers, the introduction of coffee, English drinking customs, and much, much more.

The resulting book is, admittedly, not for everyone: its anecdotes pile upon one another with no hint of organization, and at times its references, to everything from Greek and Roman classics to forgotten critical contemporaries of D’Israeli, are so obscure as to render the essays impenetrable, even for a reader familiar with the period. Yet for all that, it is remarkably charming, and surprisingly approachable. The pieces are short, most but a few pages in length, and they shine with a wry wit and a love of rumor, badinage, and odd detail that makes their author seem contemporary, far more like an amiable dinner companion than a fusty scholar.

Curiosities is currently available from a handful of print-on-demand publishers. At more than 1,300 pages, spread over multiple volumes, it might be too large a project for a mainstream publisher to undertake. D’Israeli’s cascades of quotations and facts sometimes bring to mind Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, the most comparable book I can think of that’s currently in print. D’Israeli’s book has neither the reputation, historical importance, nor the later literary champions of Burton’s—but the contrast between Burton’s carefully nursed weariness and D’Israeli’s perpetual enchantment with the world makes Curiosities seem in an odd way perfectly suited for our information-saturated, over-published era: for any reader who has ever felt a twinge of despair on walking into a bookstore and being confronted by stacks and stacks of novels that are destined for oblivion, D’Israeli, with his voracious reading, capacious memory, and unabashed love of the high and low alike, is the perfect antidote. He is the reader we’ve all been looking for; he’s the reader we might wish ourselves to be, and the Curiosities is a book to pull down from the shelf and dip into over and over again throughout a lifetime.

—Levi Stahl

*****

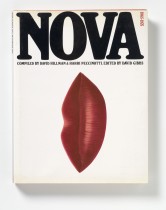

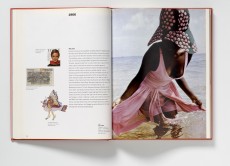

Nova: 1965-1975 (1993)

One of my favorite books last year was Bibliographic: 100 Classic Graphic Design Books

One of my favorite books last year was Bibliographic: 100 Classic Graphic Design Books by Jason Godfrey. I own a few of the more recent books included in Bibliographic, such as Paul Rand: A Designer’s Art, Designed by Peter Saville, Robert Brownjohn: Sex and Typography, Tibor Kalman: Perverse Optimist, The Graphic Language of Neville Brody, and The End of Print: The Graphic Design of David Carson, but the rest of Bibliographic is a beautifully detailed shopping list for a future library.

I’ve had to reconcile myself to the fact that I won’t ever own all these books. With at least a couple first published in the early 20th century, several of them are long out of print, and Godfrey himself only had access to them via the St. Bride Library. I thought, however, that I might be in with a chance with Nova 1965-1975.

Only published for 11 years, Nova was a provocative and pioneering British magazine known for its cutting-edge photography and imagery. Photographers Helmut Newton, Terence Donovan, and Diane Arbus were regular contributors, as were illustrators and artists Peter Blake and Alan Aldridge. According to Godfrey, “Nova was published during a period in the late 1960s when Britain was a center of the world’s attention in fashion, music and the arts. As such Nova was a reflection of the atmosphere and creativity of its time.”

Only published for 11 years, Nova was a provocative and pioneering British magazine known for its cutting-edge photography and imagery. Photographers Helmut Newton, Terence Donovan, and Diane Arbus were regular contributors, as were illustrators and artists Peter Blake and Alan Aldridge. According to Godfrey, “Nova was published during a period in the late 1960s when Britain was a center of the world’s attention in fashion, music and the arts. As such Nova was a reflection of the atmosphere and creativity of its time.”

Published in 1993 by Pavilion Books and compiled by David Hillman and Harri Peccinotti, two of the magazine’s original art directors, Nova 1965-1975 is, Godfrey says, “the visual story of the magazine’s evolution told largely through its covers and spreads.” I assumed, a bit naively, that the book’s relatively recent publication meant I’d be able to find a reasonably cheap copy. I was quickly disabused by AbeBooks, where even worn copies start at about $440! Needless to say, I’m saving my pennies, and the book is still on that shopping list.

—Dan Wagstaff

(Images of Nova 1965-1975 from Bibliographic: 100 Classic Graphic Design Books by Jason Godfrey with photographs by Nick Turner.)

*****

Inside the Art World: Conversations with Barbaralee Diamonstein (1994)

Reader, I hesitate to inform you about this book. Part of me hopes it stays out of print—sorry, Barbaralee Diamonstein—because no one who gets his or her paws on it can fail to become a better art journalist. And in truth, I don’t want better art journalists out there. The industry is already glutted. Who needs the competition?

Reader, I hesitate to inform you about this book. Part of me hopes it stays out of print—sorry, Barbaralee Diamonstein—because no one who gets his or her paws on it can fail to become a better art journalist. And in truth, I don’t want better art journalists out there. The industry is already glutted. Who needs the competition?

This book was, at the epiphanic moment when I discovered it, lodged among dust bunnies on the upper shelf of the library of an art gallery where I worked. The gallery’s staff, myself included, had been put to work clearing out the space in preparation for a move to a larger space. As a college art history student with a budding interest in the art world’s byzantine byways, I pored over Diamonstein’s work, a collection of interviews with luminaries: rainmaker dealers like Arne Glimcher and Larry Gagosian and the late Leo Castelli, the lion in winter; artists like Chuck Close and Jasper Johns; museum honchos like the redoubtably, intimidatingly French Philippe de Montebello. Best of all, there was a string of photos running along the top of each page, like film stills, taken over the course of the interviews. Gagosian looked relaxed, at ease behind a sprawling desk, tie comfortably askew. At one point he’s on the phone; dealmaking, presumably, interviewer be damned. Behind him is what appears to be a Jackson Pollock painting. Relaxed! And the interview had been done in the early ’90s, during a recession.

I could tell you more about this book, about the late Robert Rauschenberg, cigs and—it must be—whiskey on the rocks to hand; about a youngish Tom Krens, on the cusp of the Guggenheim’s manic global expansion; a grinning, cherubic Jeff Koons; a somber-looking Richard Serra. (“My input was to build the bridge, not to build the fish.” That’s out of context. Still.) But you know what? Never mind. I’m better off for your not knowing about it.

—Sarah Douglas

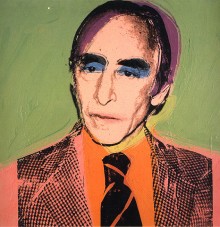

(Image: Leo Castelli 1975 by Andy Warhol)

*****

Love is the Heart of Everything: Correspondence Between Vladimir Mayakovsky and Lili Brik edited by Bengt Jangfeldt (1987)

My dear and beloved kitten I kiss you terribly, terribly. All yours with all four paws, Shchen. I kiss Oska on his whiskers—this from the poet Stalin called the “Hero of the Revolution,” even ominously suggesting that “indifference to his work is a crime.” But what of indifference to his outsized love? When Vladimir Mayakovsky (the aforementioned Shchen, or “puppy”) first met Lili Brik (”kitten”) in the summer of 1915 he fell impetuously in love, and eventually into a ménage à trois with her and her husband Osip (the bewhiskered Oska). Love Is the Heart of Everything traces the highly charged relationship between these seminal figures of the Russian avant-garde through their frequent if none-too-revolutionary letters from their meeting just before the October Revolution until Mayakovsky’s suicide in 1930.

My dear and beloved kitten I kiss you terribly, terribly. All yours with all four paws, Shchen. I kiss Oska on his whiskers—this from the poet Stalin called the “Hero of the Revolution,” even ominously suggesting that “indifference to his work is a crime.” But what of indifference to his outsized love? When Vladimir Mayakovsky (the aforementioned Shchen, or “puppy”) first met Lili Brik (”kitten”) in the summer of 1915 he fell impetuously in love, and eventually into a ménage à trois with her and her husband Osip (the bewhiskered Oska). Love Is the Heart of Everything traces the highly charged relationship between these seminal figures of the Russian avant-garde through their frequent if none-too-revolutionary letters from their meeting just before the October Revolution until Mayakovsky’s suicide in 1930.

Not the least bit literary, the value of the correspondence lies in its illumination of Mayakovsky’s intense personality, of his deep involvement with the Briks, and most important, of his boundless (read “codependent”) love for Lili. And it is only through these emotionally charged letters (and the accompanying doodles of kittens and sad puppies) that one can begin to completely appreciate the undisputed, if under-confident, Poet of the Revolution—or how the poet who wrote the lovelorn “A Cloud in Trousers” could be the same to later write the patriotic and adulatory “A Conversation with Comrade Lenin.” Worry miss you love you kiss you. Your Shchen.

—Kevin Kinsella

(Image: Photo of Mayakovsky, 1924, by Alexander Rodchenko)

*****

Tropisms by Nathalie Sarraute (1939)

Nathalie Sarraute wrote like no person before her, and her Tropisms are artful and elegant like nothing else. When I found this little book of vignettes, so precious and so well wrought, on the shelf of my bookstore, I had no idea it was out of print. I bought it, devoured it, and gifted it to a friend. Days later, I couldn’t get it out of my head and I went in search of another copy. And here we are, bemoaning another out-of-print gem.

Nathalie Sarraute wrote like no person before her, and her Tropisms are artful and elegant like nothing else. When I found this little book of vignettes, so precious and so well wrought, on the shelf of my bookstore, I had no idea it was out of print. I bought it, devoured it, and gifted it to a friend. Days later, I couldn’t get it out of my head and I went in search of another copy. And here we are, bemoaning another out-of-print gem.

The genius of this book is in its striving, in the absence of plot and in the presence of newness. There is something more meaningful, more painful and truthful in this kind of writing than in mere fiction. In part, it’s Sarraute’s uncanny, wistful and bitter voice. What she created here is dryly French, and entirely compelling. The discrete sketches that make up the book are both of people and of life itself. Brilliant and brave, they force the reader to fill in all of those things the author chooses not to say, sometimes with painful results. Of how many of us here is this an awfully true portrait?

There were a great many like her, hungry, pitiless parasites, leeches, firmly settled on the articles that appeared, slugs stuck everywhere, spreading their mucus on corners of Rimbaud, sucking on Mallarmé, lending one another Ulysses or The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, which they slimed with their low understanding.

Sarraute knows when and at whom to point a finger, and these intimate chapters are a window onto the themes and characters that she most wanted to explore in her later work. With the slime of my own low understanding, I present to you my OP darling.

—Jeff Waxman

*****

Blood Money by Francis Rufus Bellamy (1947)

The academic library isn’t built for browsing. Its book spines bear a title and call number, but no author, publisher, graphic, photo, or even telling font choice. I began wandering it only to avoid writing papers, but I soon discovered that it’s ripe for serendipity, its out-of-print meats salted away over decades by monomaniacal bibliolaters. I found the impetus for my doctoral dissertation amid the particularly neglected music-history stacks of NYU’s abominable Bobst Library (a storage facility devoted to wasting space that incarnates not the life of the university but its death).

The academic library isn’t built for browsing. Its book spines bear a title and call number, but no author, publisher, graphic, photo, or even telling font choice. I began wandering it only to avoid writing papers, but I soon discovered that it’s ripe for serendipity, its out-of-print meats salted away over decades by monomaniacal bibliolaters. I found the impetus for my doctoral dissertation amid the particularly neglected music-history stacks of NYU’s abominable Bobst Library (a storage facility devoted to wasting space that incarnates not the life of the university but its death).

It was also in Bobst, in a section on mid-century economic history that seemed equally unpromising, that I found the 1947 volume Blood Money by a former New Yorker editor named Francis Rufus Bellamy. “This is not a pretty book. On the contrary, it is filled with as unpleasant a lot of people as you are ever likely to meet.” The book describes America’s efforts to bankrupt the Axis. Bellamy dips his pen in so much red, white, and blue that it shades purple, but no matter. In June 1941, America, officially at peace, seized the assets of over 3,700 men against whom it had no evidence, solely because they had foreign ancestry or business. More than a few were guilty. The well-connected won secret permission to continue trading with the enemy, as later books have shown. But Bellamy’s account, built from official files, focuses on the colorful profiteers who tried to wriggle away—among them a taxi driver, a pig smuggler, Hedy Lamarr’s husband, and Chile’s ambassador to Mexico—and the feds who hunted them down. “As a matter of fact, the Treasury itself is the only hero the book has,” he writes. The Treasury, a hero!

—Jon Lackman

*****

Essays in Disguise by Wilfrid Sheed (1990)

I’ve written about this book before, but that’s one of the nice things about running the place: You don’t have to look far for permission to repeat yourself.

I’ve written about this book before, but that’s one of the nice things about running the place: You don’t have to look far for permission to repeat yourself.

Sheed, now 79, has published more than a dozen books—novels, memoirs, paeans to baseball, collections of his literary criticism—and nearly all of them are out of print. In gathering book reviews, longer essays on broader subjects (including the Catholic Church and the Mafia), and shorter pieces on prejudice, sin, money, golf, and more, Essays in Disguise is arguably the most balanced, representative collection of his work. It’s deeply smart, hysterically funny, and impossible to resist quoting, which you’ll see if you go back and read that original review. In fact, I’ll excerpt it once more; Sheed’s words are the best way to sell his work. This is the opening of one review:

The vanity of poets is one of the three or seven (I forget the latest figure) basic jokes of mankind, so there’s no pretending it isn’t funny. Yet laughing at it can be almost as cruel as making fun of somebody’s gout. Poet’s Vanity is an extremely painful condition, and there is absolutely nothing the victim can do about it. If one has made something beautiful enough, one needs to be praised for it, as God is praised every Sunday for His universe. And all the foot-shuffling and hair-rumpling modesty of a Robert Frost only makes it worse.

Poets who get their full measure of glory tend to sprout beautiful heads of white hair and to live a long time. Poets who, on the whole, don’t are the subject of Eileen Simpson’s amiable book Poets in Their Youth.

In the sense that my favorite under-appreciated writers were a large part of the inspiration for The Second Pass, Sheed is one of the site’s progenitors. I can’t recommend him highly—or, evidently, often—enough.

—John Williams

*****

About the contributors: John Davidson is a freelance writer and critic living in Austin, Texas. . . . Andy Miller is the author of three books. He lives in England. . . . Ranylt Richildis is an eighteenth-century literature scholar and film critic. . . . Jacob Silverman is a contributing online editor at the Virginia Quarterly Review who has written for the Los Angeles Times, New York Times, VQR, and other publications. . . . Matt Weiland is senior editor at Ecco and co-editor, with Sean Wilsey, of State by State: A Panoramic Portrait of America. . . . Among many other things, Levi Stahl blogs at I’ve Been Reading Lately. . . . Dan Wagstaff works in sales and marketing for Raincoast Books, and blogs at The Casual Optimist. (Full disclosure: Bibliographic is distributed in Canada by Raincoast Books). . . . Sarah Douglas is a staff writer for Art & Auction. . . . Kevin Kinsella is a writer and translator living in Brooklyn whose translation of Osip Mandelshtam’s Tristia

, from Russian, was published by Green Integer Books. . . . Jeff Waxman is a bookseller with the Seminary Cooperative Bookstores in Chicago, and the editor of their web magazine, The Front Table. His reviews have appeared in the Review of Contemporary Fiction, Three Percent, and elsewhere. Currently, he blogs for The Constant Conversation. . . . Jon Lackman has written for Slate and Harper’s and is the editor of ArtHistoryNewsletter.com. . . . John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.

*****

Mentioned in this feature:

(In cases where these books appear to be currently offered from print-on-demand services, which can be prone to the production lapses that a couple of contributors above cautioned about, I’ve put an asterisk next to the title as fair warning.)

The Disenchanted

Krautrocksampler

Memoirs of the First Forty-Five Years of the Life of James Lackington*

Past Continuous

Killings

Curiosities of Literature*

Nova 1965-1975

Inside the Art World

Love Is the Heart of Everything

Tropisms

Blood Money

Essays in Disguise