Reviewed:

Absolute Beginners by Colin MacInnes

1959, 208 pp., Currently out of print

Last summer I finally saw Jacques Demy’s 1967 musical Les Demoiselles de Rochefort. Catherine Deneuve and Françoise Dorléac play non-identical twin sisters—a ballet teacher and singing teacher, respectively—who dream of escaping to Paris and finding fulfillment and true love. Over the course of one weekend, to the accompaniment of Michel Legrand’s boutique jazz score, they sing and dance their way to the kind of ultra-happiness that only a good musical can deliver.

I am not ashamed to say I like musicals very much. I also like the nouvelle vague, so I came to Les Demoiselles fully expecting to be enchanted. And I was; in fact, my expectations were surpassed. The film is exquisite, ludicrous and beautiful at the same time. Staging an MGM-style extravaganza in a real place and time—the south-western port of Rochefort in the summer of 1966—Demy distills something like pure joy from a muddle of imperfections: drab streets, dislikeable characters, unbelievable coincidences, and two leading ladies who can neither really dance nor sing (and who give the impression that teaching either skill is obviously beneath them).

In Demy’s world, characters break into and out of song at the most improper moments. At one point, a local café owner (the heroines’ mother) and her customers discuss—or rather, start trilling in syncopation—the grisly specifics of a local psychotic murder:

Everyone is in an uproar

It seems he used an axe or saw

He cut her into bits

And laid her out like a puzzle kit

These lines are delivered not in horror but with a classic Gallic shrug—la mort, c’est la vie—with the result that while we might pause and consider the characters’ attitude to death and dismemberment, we never question their decision to sing about it.

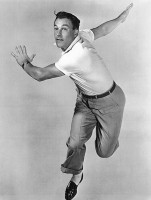

Les Demoiselles de Rochefort features one of the final big screen appearances of Gene Kelly who, although only in his early 50s, had already outlived the era in which a dancer and choreographer of his genius was permitted to make movies. (Kelly would live for another 30 years, during which time he appeared in only three more original features, the last of which was Xanadu with Olivia Newton-John.) In recent weeks and months, I had become fascinated by Kelly, whose aesthetic of athletic, masculine dance defined his Hollywood career. We—that’s my wife and I—had watched the documentary Anatomy of a Dancer and worked our way through half a dozen of Kelly’s films, including An American in Paris, Singin’ in the Rain, and The Pirate with Judy Garland. The Pirate is one of the weirdest and, yes, campiest MGM musicals of the lot—a real ragbag score and Garland vibrating with studio-prescribed meds and high anxiety—but Kelly is spectacular. There is a sequence near the beginning of the film where, while dancing and singing the tongue-twisting Cole Porter composition “Nina”—sample rhymes: “gardenia,” “neurasthenia,” and “schizophrenia”—in short order Kelly does this: vaults up the side of a building, swings from an overhanging metal beam, slides down a handily-placed pole to ground level, borrows a lit cigarette from a smoking senorita, curls the gasper into his mouth using just his tongue, passionately kisses the senorita full on the lips, disgorges the cigarette, blows a farewell puff of smoke in her face—and all this as the mere preamble to a four-way Paso Doble (Gene now juggling three senoritas at once) and a sinew-straining solo ballet routine involving a bandstand and some more poles. That really is entertainment.

The film Kelly made prior to Les Demoiselles was the big-budget studio comedy What a Way to Go!, starring Shirley MacLaine. [1] Kelly plays Pinky Benson, a tragically corny nightclub hoofer. By this point (1964), the only way Kelly could get to dance on screen was by sending himself up. Pinky’s nightclub shtick is so dire, yet delivered with such heartbreaking super-sincerity, that MacLaine is moved to observe, “It was the worst act I had ever seen. Just looking at Pinky made me want to cry.” Of course, the gag works because of Kelly’s commitment to sending himself up properly—he sings and dances, badly, as if his life depends on it, wherein lies the joke. As my wife said, “Gene Kelly would rather die than phone it in.”

So we knew Gene Kelly was going to make an appearance in Les Demoiselles de Rochefort and we knew he would be great. But about twenty minutes into the film—with Gene yet to appear—Françoise Dorléac says this: “I plan to go to Paris next week. You hinted, last Tuesday, you could recommend me to your friend, Andrew Miller, the composer.”

Strike up the band! By a Technicolor twist of fate, Gene Kelly’s character in the film and I had been blessed with the same name. On me, “Andy Miller” was unremarkable. But on Gene . . .

Thus, in the film, it is Andy Miller who wanders into Michel Piccoli’s shop wearing daring pastel pink and lavender. Andy Miller is a world-famous concert pianist. When Andy Miller gives one of his trademark grins, the whole room lights up. Who’s that mec tap-dancing with sailors, duetting with the neighborhood kids, leaping into a snazzy sports car and zooming off into the distance with a merry wave of the hand? It can only be Andy Miller. Who gets the girl? Andy Miller does.

And so on.

Needless to say, this coincidence was a source of great celebration in the Miller household (the generally dreary non-pastel one, sans sports car). It seemed like some kind of triumphant, extrasensory proof that this film really belonged to us. Which is why I have been telling you so much about Gene Kelly, and in such a self-regarding manner, too. Enthusiasm creates its own momentum, for books or films or whatever, and creates its own rewards, too—if you let it. As you get older, it becomes more difficult to tune into that sense of limitless opportunity. Real life drums it into you that people rarely burst into song on street corners unless they are drunk or mad. But every so often you might chance upon a song or a book which makes you feel you can run up the side of a tall building, or chop a neighbor into bits and lay her out like a puzzle kit.

Needless to say, this coincidence was a source of great celebration in the Miller household (the generally dreary non-pastel one, sans sports car). It seemed like some kind of triumphant, extrasensory proof that this film really belonged to us. Which is why I have been telling you so much about Gene Kelly, and in such a self-regarding manner, too. Enthusiasm creates its own momentum, for books or films or whatever, and creates its own rewards, too—if you let it. As you get older, it becomes more difficult to tune into that sense of limitless opportunity. Real life drums it into you that people rarely burst into song on street corners unless they are drunk or mad. But every so often you might chance upon a song or a book which makes you feel you can run up the side of a tall building, or chop a neighbor into bits and lay her out like a puzzle kit.

In other words, when that pure joy comes along, make like Gene and grab it.

****

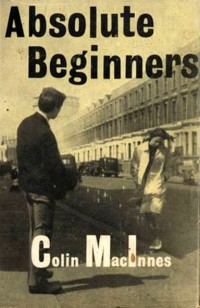

Have you ever read Absolute Beginners by Colin MacInnes?

Recently, Radio 4 in the UK ran a series of programs called The Movie That Changed My Life. In general, I don’t believe in this formula, which has in recent times become a cliché much loved by culture supplement editors. Culture only changes your life to the extent that you are committed to both a) culture and b) changing your life. It’s the overture, not the show. In themselves, books, films and records usually don’t change lives; anyone who claims they do is probably trying to sell you something. And hey ho, close scrutiny of The Movie That Changed My Life reveals not people whose actual lives have been actually changed by movies—a nun taking shelter from a sudden downpour, say, and accidentally stumbling into a screening of Ken Russell’s The Devils—but instead a few minor celebrities who happen to like a film enough to talk about it on the radio for money.

The book Absolute Beginners, by contrast, has changed my life twice, really changed it. Of course, I think it’s a wonderful novel—if someone were willing to pay me to talk about it on the radio, I would be only too happy to take the dirty money—but I am thinking of an effect more tangible than just enjoyment or appreciation or the comforting impression, normally lasting only a few days, that one is thinking fresh thoughts and seeing the world as it really is. No, Absolute Beginners has twice altered the course of my life—though perhaps not always for the better.

I got a Coke, and went and gazed, and it certainly was a sight! All those aircraft landing from outer space, and taking off to all the nations of the world! And I thought to myself, standing there looking out on all this fable—what an age it is I’ve grown up in, with everything possible to mankind at last, and every horror too, you could imagine! And what a period it’s been in England, what a time of fun and hope and foolishness and sad stupidity!

Colin MacInnes is an unlikely figure to have written the greatest teenage book of them all. He was born in 1914, the cousin of Stanley Baldwin and Rudyard Kipling, and grandson of the artist Edward Burne-Jones, and was brought up in Australia. Absolute Beginners is the second of three books loosely referred to as “The London Trilogy”: City of Spades (1957), Absolute Beginners (1959) and Mr. Love and Justice (1960). Their setting is London in the second half of the 1950s, the new postwar London of immigrant communities and coffee bars and teenagers with cash to spend and new places to spend it. This is where MacInnes lived and worked, the streets of Soho and Ladbroke Grove, many years before those areas become synonymous with gentrification and white-boy trustafarianism.

In City of Spades, the narrative is shared between Montgomery Pew, an Englishman, and Johnny Fortune, newly arrived from Nigeria; its setting is the new exotic London which was springing up inside the old one. Mr. Love and Justice is more hard-boiled, a London noir of youthful cops and ponces and prostitutes. Absolute Beginners, meanwhile, concerns itself with another phenomenon of the era—the “teen-age thing.” Over the course of four summer months/chapters, the unnamed hero of the novel, 19, a photographer, makes his picaresque progress through the West London of “Napoli,” a name coined by MacInnes to encompass Notting Hill and Ladbroke Grove. The story culminates in a race riot from which the narrator and his girl narrowly escape with their lives. In the book’s bittersweet final pages, the photographer greets a party of Africans, newly landed at Heathrow Airport:

In City of Spades, the narrative is shared between Montgomery Pew, an Englishman, and Johnny Fortune, newly arrived from Nigeria; its setting is the new exotic London which was springing up inside the old one. Mr. Love and Justice is more hard-boiled, a London noir of youthful cops and ponces and prostitutes. Absolute Beginners, meanwhile, concerns itself with another phenomenon of the era—the “teen-age thing.” Over the course of four summer months/chapters, the unnamed hero of the novel, 19, a photographer, makes his picaresque progress through the West London of “Napoli,” a name coined by MacInnes to encompass Notting Hill and Ladbroke Grove. The story culminates in a race riot from which the narrator and his girl narrowly escape with their lives. In the book’s bittersweet final pages, the photographer greets a party of Africans, newly landed at Heathrow Airport:

Some had on robes, and some had on tropical suits, and most of them were young like me, maybe kiddos coming here to study, and they came down grinning and chattering, and they all looked so dam (sic.) pleased to be in England, at the end of their long journey, that I was heartbroken at all the disappointments that were in store for them. And I ran up to them through the water, and shouted out above the engines, “Welcome to London! Greetings from England! Meet your first teen-ager! We’re all going up to Napoli to have a ball!”

Up to a point, MacInnes’ vision of this London was informed by experience. He had lived in the areas he wrote about and spent time amongst their inhabitants, but he was necessarily an outsider—white, practically Australian, and in his early 40s when he wrote the books. But this isn’t reportage, it is fiction, where fabulous events can bloom on the gloomiest of streets. As Francis Wyndham wrote in London Magazine in the late 1960s:

Because Colin MacInnes has chosen subjects normally dealt with in Reports by Commissions, or even less responsibly by ignorant journalists, these three novels when they first appeared were treated almost unanimously by reviewers as “documentaries.” On the contrary, they are lyrical approximations to reality: highly imaginative and on occasion frankly fantastic approaches to themes of which no other contemporary novelist has yet shown himself properly aware. The author was trying to close that dreary gap which often exists between life and art and is kept clear for journalism: just because immigrants, teenagers and prostitutes are favorite newspaper fodder, “imaginative” novelists had tended to steer clear of them altogether, at the most introducing them through stylized secondary characters who were either borrowed from comic stock or absurdly dignified by a sentimental treatment. No responsible novelist before Mr. MacInnes had taken the trouble to find out what reality was represented by these convenient dummies.

Absolute Beginners was a modest success when it first appeared, probably the most successful novel MacInnes published in his lifetime (he died in 1976). But its afterlife—from publication to the present day—is fascinating. It is a great rarity in British writing, a homegrown cult novel about what it means to be young, and it has a rhythm unlike any other British novel of the period. This is partly because MacInnes was attempting a feat of double literary ventriloquism—his young hero speaks (I doubt he is meant to have written the words on paper) in an Anglicized approximation of the Beats, specifically Kerouac, a corollary to the imported jazz which plays such an important part in the book (pop and rock’n’roll, by contrast, are strictly for the kids). This could just be embarrassing, couldn’t it? But it works because of the humor and energy and forward motion MacInnes puts into the book. He throws himself into the task, the palpitating drumbeat of a final teenage summer:

I saw I was breaking one of my golden rules, which is not to argue with Marxist kiddies, because they know. And not only do they know, they’re not responsible—which is the exact opposite of what they think they are. I mean, this is their thing, if I dig it correctly. You’re in history, yes, because you’re budding here and now, but you’re outside it, also, because you’re living in the Marxist future. And so, when you look around, and see a hundred horrors, and not only musical, you’re not responsible for them, because you’re beyond them already, in the kingdom of K. Marx. But for me, I must say, all the horrors I see around me, especially the English ones, I feel responsible for, the lot, just as much as for the few nice things I dig.

Is this how 19-year-old West London photographers thought about politics—let alone talked—at this time? Of course not. But in its blend of speed and savvy and bluff, MacInnes captured something essential to nascent teenage identity which, though the book’s popularity has come and gone in the intervening 50 years, we can still easily recognize today—the compulsion to be right. (In comparison, the earlier The Catcher in the Rye doesn’t do a bad job but there is something self-consciously literary about it which makes H. C. feel rather, well, phony.)

I first came to Absolute Beginners in 1984, when the book was probably at the height of its popularity. Paul Weller was its most famous advocate, and his group The Jam had released a single with the same title. [2] A film was in production. It was one of those novels which, if you were 16 as I was, you needed to have read. [3] I raced through it in a day, whilst on holiday with my parents in Scotland. Yeah! My body may have been on the car deck of a Caledonian MacBrayne ferry between Oban on the mainland and the historic Isle of Iona but my heart was in the jazz joints of Napoli. Dig!

I remember finishing the book while sitting up on deck on the return crossing, oblivious to the Scottish summer gale which battered the boat. I had never been grabbed by a book in quite the way Absolute Beginners grabbed me (not even Doctor Who and the Brain of Morbius). It engaged me intellectually, emotionally—completely. I felt it spoke to me and for me. I have a photo of Mum and Dad I took on Iona that afternoon, standing in front of its medieval abbey. It is the last photograph of my childhood, my parents as I saw them when I was still the junior member of our small family (my father died the following year). When we got home, I was not the same. I was at long last a teenager; no, not a teenager—a young adult. I could see a path out of childhood.

So Absolute Beginners gave me an exit strategy, a teenage identity I could relate and aspire to. In the process, it liberated and liberalized me—awakened in me the nervous excitement of being young, on the brink, in the same way that great pop music does. At a stroke, it made me more tolerant towards difference of many kinds. It made me feel all right. It changed my life.

I read the book several times in late adolescence. Its spell never diminished. I went out into the world and forgot about it, let it become a memory. Then, in the dying months of my 30s, I re-read the book for the first time in 20 years and it turned me upside down all over again. Variously, I felt: homesick, elated, angry, exhilarated, righteous, and all right. I felt vindicated. When I was 16, I’d known where it was at.

At this time I was working in West London. I had made a life in books. The company’s office was in Ladbroke Grove, exactly where the novel is set; we lived nearby with our young son. In the week I read the book again, the British National Party made significant gains in London at the local council elections. It was depressingly easy to transpose the 1950s race riots of the novel to the streets around me; their names, after all, had not changed. But the book didn’t just draw a line between the present and the past (my present and my past), it made me feel they were happening simultaneously—a superimposing of the 1950s (the events of the book), the 1980s (me when I first read it), and my life in the 21st century, its likely future, a telescoped view of the whole ambiguous relationship between me and London and books.

Every job I get, even the well-paid ones, denied me the two things I consider absolutely necessary for gracious living, namely—take out a pencil, please, and write them down—to work in your own time and not somebody else’s, number one, and number two, even if you can’t make big money every day, to have a graft that lets you make it sometime. It’s terrible, in other words, to live entirely without hope.

Shortly afterward I resigned from my job and we left London to live on the coast; to build Napoli-on-sea. Absolute Beginners had helped change my life again.

****

So, what happened to Absolute Beginners? I suspect the book is not widely read now, even in England. There was a period in the 1990s when it was out of print here; indeed, at the time of writing, it is only available as part of a “London Novels” omnibus. And in fact it was comparatively little read by the end of the 1980s, just five years after I discovered it. In the era of ecstasy and Acid House, its recent popularity suddenly felt like an uptight throwback. Thirty years after publication, and for the first time, it had become unfashionable. Why?

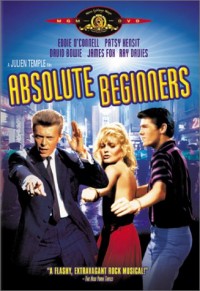

The answer is the film. They made a bad musical out of Absolute Beginners, and in doing so flushed its credibility clean away. If Les Demoiselles de Rochefort epitomizes the precarious delights of a musical done right—the unlikely elements in harmony—then Julien Temple’s movie of Absolute Beginners is its anti-matter, a black hole which sucked in not just the book and its reputation, but also much of the British film industry.

The catastrophic failure of Absolute Beginners was told at length in My Indecision Is Final: The Rise and Fall of Goldcrest Films by Eberts and Ilott. Even in 2010, the film (and by association the novel) is synonymous with everything flash and crass and non-revivable from the 1980s—giant mobile phones, “Love Missile F1-11,” Absolute Beginners. [4] So I will confine myself to writing about the two occasions on which I have seen it.

The catastrophic failure of Absolute Beginners was told at length in My Indecision Is Final: The Rise and Fall of Goldcrest Films by Eberts and Ilott. Even in 2010, the film (and by association the novel) is synonymous with everything flash and crass and non-revivable from the 1980s—giant mobile phones, “Love Missile F1-11,” Absolute Beginners. [4] So I will confine myself to writing about the two occasions on which I have seen it.

The first was in 1985, on the first day of the film’s general release (I have a close friend who attended the London première, a sensational event at the time but something he doesn’t talk about much these days). I sat in the Astoria, Purley, on a Friday afternoon, and watched in bewilderment as a succession of characters and incidents from the book went wrong before my very eyes. I didn’t dislike the film, exactly, not least because I so wanted to find the good in it. Several of my musical heroes were involved—Weller, Elvis Costello, Ray Davies, David Bowie (Bowie’s theme tune was already a big hit, and I still have a soft spot for it). And, you know, it was my favorite book. But standing by his car after the film was over, my best friend Matthew and I agreed that whatever its finer points—the much-publicized Soho tracking shot, a song or two, the “Quiet Life” set piece where the family home is opened up like a doll’s house—as an adaptation of the book, Absolute Beginners was completely useless. Never mind, we said, maybe more people will read the book and find that out for themselves.

Of course, they didn’t. What happened was the book, licensed to Penguin in a mass-market deal, with a new cover bearing the movie’s logo and photographs of the stars, remained as lingering evidence of the failure of the film. And whereas the movie had disappeared from cinemas within weeks, the tie-in edition of the book, which Penguin had printed in vast quantities, anticipating a bestseller that never came, hung around bookshops for years afterward, looking nothing but cheap and un-hip and utterly without promise. By the time this edition was pulped, there was no fresh version to replace it; the market was flooded with a great book nobody wanted.

I saw the film again recently. At nearly 25 years’ distance it seemed pitifully obvious what had gone awry with the whole project. It had been made by people who, while they embraced the cultural cachet of the source material, didn’t really get it—and therefore what appeared on screen mimicked what was on the page but had no life of its own. [5] And unfortunately this clueless, cynical fidelity to the text also encompassed the whole genre of film musical itself. No one in this musical makes anything look easy. Ultra-happiness is in short supply.

The greatest disservice the film does to MacInnes’ book is this: by stylizing everything—every street, every scene, every character—we simply don’t care about anything or anyone in the film. None of it is real. Whereas in the book, MacInnes built his stylized characters and stories on a foundation of documentary realism, and then animated them with wit and imagination. If you want to see how poor and grimy West London really was in the era MacInnes was writing about, take a look at late ’60s films like 10 Rillington Place or John Boorman’s Leo the Last or even Performance. That London was still grim. But then imagine Technicolor characters flitting across its surface, Demy-style. What a movie that would be. What a book.

Albert Camus once wrote, “A man’s work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.” I like to connect Absolute Beginners (the book) and Les Demoiselles de Rochefort in just this way—as both the image and the detour. The secret of the slow trek is to keep moving forward.

That Camus quote is emblazoned on the cover of Scott Walker’s 1969 LP Scott 4, which is where I first encountered it. Walker is an artist who has moved forward incrementally, his bursts of noise and activity punctuated by 10-year silences while he waits for something new to say. In an interview published a few years ago, Walker was asked why he had so dramatically changed the style of his music in the late 1970s: “I suddenly woke up . . . I’d acted in bad faith for so long I’d lost my heart for the world, sort of. I had to discover my life again, to just do it for me alone. So I made the decision: no more bad faith.”

Bad faith is what happened to Absolute Beginners and I suppose to me; but by finding the book again, I remembered the importance of keeping faith with “those two or three great simple images.” I discovered my life again. And so I moved on.

Jacques Demy died in 1990. His widow, the filmmaker Agnès Varda, 81, has devoted much of the last 20 years to curating his work and ensuring his legacy. In a recent profile in the Guardian, she talked about her own film The Beaches of Agnès. In one scene, she shows us an old friend, Andrée, whose memory has deteriorated to the point where she can recall nothing but poetry, which she likes to recite to herself. Varda’s response to this is simple and crystallizes the aesthetic she shared with her late husband: “It gives you hope that life is not just reality. I hope if it happens to me that I remember Baudelaire, Prévert, Aragon and Rilke, and just forget the rest.”

[AND SO ANDY MILLER GIVES A DAZZLING GRIN, CLIMBS INTO HIS SPORTS CAR AND, WITH A GENE KELLY-LIKE WAVE, DRIVES OFF INTO THE PERFECT SUNSET.]

FIN

Andy Miller is the author of three books. He lives in England.

[1] What a Way to Go! is chiefly remarkable for MacLaine’s motley crew of leading men—Kelly, Dick Van Dyke, Dean Martin, Robert Mitchum and, of all people, Paul Newman—and a nonstop parade of Edith Head’s loveliest and looniest gowns for MacLaine. Cost? $700,000 for the gowns alone. In 1964. The film was a stupendous box-office disaster.

[2] Paul Weller, like Morrissey, is someone with a single-minded loyalty to his teenage self. When he appeared on Desert Island Discs in 2007, aged 49, he chose Absolute Beginners as the book he would take with him to the desert island.

[3] A British teenager’s reading list in 1984 might typically consist of Orwell, Brighton Rock, Brave New World, and the plays of Joe Orton, as well as the unofficial American set texts like The Catcher in the Rye, On the Road, and Catch-22.

[4] In the words of the group Denim, from the album Back in Denim, “I’m Against the Eighties.” Was then, am now.

[5] This is exactly what afflicted the recent adaptations of Alan Moore’s Watchmen and, to a lesser extent, V for Vendetta, both of which seemed to have been made by highly talented and lavishly funded savants.

Mentioned in this review:

Absolute Beginners

The London Trilogy

The Young Girls Of Rochefort

Gene Kelly: Anatomy of a Dancer

An American in Paris

Singin’ in the Rain

The Pirate

What a Way to Go!

Absolute Beginners (the movie)

Doctor Who the Brain of Morbius

The Catcher in the Rye

My Indecision Is Final: The Rise and Fall of Goldcrest Films

Scott 4

The Beaches Of Agnes