Reviewed:

Reviewed:

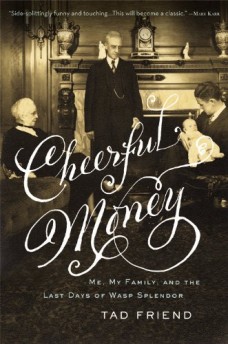

Cheerful Money: Me, My Family, and the Last Days of WASP Splendor by Tad Friend

Little, Brown, 368 pp., $24.99

It would be possible to make three good, small books of Cheerful Money. Not that I’m suggesting anyone chop it up with a kitchen knife, as Janet Malcolm did to The Making of Americans by Gertrude Stein. I’d just like to imagine the book, for a moment, in three bindings rather than one, with the history of Tad Friend’s family, Friend’s reading of WASP culture, and his memoir of his own life — the three stories mixed together in Cheerful Money — each standing on its own.

The best of these mini-books would concern the symbols of WASPdom. It would include Friend’s description of the “WASP fridge,” its “out-of-season grapes, seltzer, and vodka . . . both 1 and 2 percent milk, moldy cheese, expired yogurt, and separated sour cream” and, sitting atop, “Pepperidge Farm Milanos, Fig Newtons, or Saltines — some chewy or salty or otherwise challenging snack.”

WASPs love “getting dirty . . . in a game of touch football,” Friend explains, mud being their “only sanctioned form of filth.” They name their dogs after liquor — Bourbon, Asti, Cloey (for Clos du Boi), and Casey (for “case of beer”) are the names of some of the dogs owned by Sally, a classmate of Friend’s at boarding school. They “cream off family names as given names” (Mortimer, Courtlandt, and Whitney being examples of such “creamed” first names). And they hang onto everything they’ve ever owned: “etched-crystal wineglasses” and “pedestaled fruit plates” and “egg spoons of translucent horn” are some things they may expect to inherit.

These choice observations, and many more like them, if collected in a small volume, would remind some readers of the best-selling Official Preppy Handbook, though without that book’s direct satire or — as Preppies can be made but WASPs are born — potential sales. (Though it was a satire, many people read the Handbook as a style manual, including Friend himself, as he confesses here.)

WASPs are “circumscribed less by skin tone and religion” than by a “cast of mind.” They’re born into families that harbor firmly fixed views, carried over the generations, about minor matters. Friend recalls a running dispute between his great uncle, Wilson Pierson, who descends from a line that pronounces tomato “tomayto,” and his mother, Elizabeth, whose own mother was in the “staunchly Anglophile ‘tomahto’ camp.” When she would ask Wilson for a “tomahto,” Wilson would snap, “Would you like some potahtoes with that?” The WASP mind, Friend explains, is “excessively tuned to such questions as how you say tomato.”

Another marker, of course, is a generations-long history of wealth. Friend’s own richest relative, his great great grandfather, Big Jim Friend, left his heirs $15,000,000, the equivalent of $345,000,000 today, though most of that money was lost — much of it squandered over many years maintaining a three-house compound with eighteen servants on Pittsburgh’s Squirrel Hill, and some of it drained by the Depression. Friend doesn’t fix on an amount of money that separates a WASP from an ordinary Anglo, but any reader will quickly grasp how very few families legitimately deserve the appellation. Friend’s maternal great grandfather, Charles Pierson, was a Yale valedictorian and Manhattan corporate lawyer, and it was the Pierson family summer house, an eight-bedroom mansion on Georgica Pond in Long Island, where the “tomahto” spats unfolded. WASPs are people whose quibbles about language have an ocean view.

Friend’s portraits of men such as Jim Friend and Charles Pierson, which account for more pages than either of the other two strands of the book, tell in their aggregate a story of decline. Theodore Wood Friend, Big Jim’s son, was an incompetent bank president who had “skinny legs and a care-worn appearance that made him look old when he wasn’t, and ancient when he was.” His son (the author’s grandfather), Ted Friend, talked up dive bomb stocks — Nerlip Mines, Red Rock Cola, and laughably, Hygienic Telephone — before his brokerage firm fired him. Before he was fifty, he’d “retired to playing backgammon” at the Pittsburgh club.

Tad’s father, Dorie Friend, brought to his marriage, in 1960, a relative pittance: less than $50,000. That was still a lot of money, but it went fast. Friend remembers wondering why he could “see the road through the rusted floor” of the family station wagon.

WASP fortunes began to turn in 1965, three years after Friend was born. That was the year Yale’s new admissions director, R. Inslee “Inky” Clark, dramatically reduced the allotment of spots for alumni offspring to 12 percent from 20; the year it first became clear that “the WASP elite running the war” in Vietnam “hadn’t a clue.” It was also the year Lyndon Johnson mandated affirmative action for government employees and, perhaps of most significant symbolism, “the country’s most famous and exclusive clubs stopped updating their look and feel.” Today, as in 1965:

If you go to these clubs for dinner on a Saturday night, you get Scotch-plaid-upholstered furniture in the vintage cherry or English tavern finish; accordion-folded napkins in water glasses and sourdough rolls on the bread plates. . . . And, for company, an elderly gent in the corner in a striped three-piece suit.

The gradual erosion of the fortunes of the Friend family, then, was the manifestation of a broader trend. The Friends are not the only WASP family whose stories of fortunes triumphantly amassed — which, in the case of Big Jim, involved evicting striking Pressed Steel Car Company workers from their homes and a clash between those workers and his “Coal and Iron Police” that killed 12 people — are all but eclipsed by stories of gradually (then suddenly) losing them.

There are dozens of these family portraits, more than any reader will want to manage. Because the mini-biographies don’t follow a chronological order, and accounts of the different branches of Friend’s family are interweaved, the names and generations begin to blur. And few of the profiles are long enough to probe deeper mysteries of character.

But Friend’s expert descriptions make up for the jumble, particularly those of relatives who have spent their lives chafing against expectations. His cousin Norah became pregnant at age 19 while a second-year student at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. She put the baby up for adoption and later had two abortions. In Santa Fe, she used her father’s money to build “the Flintstone House,” an “ordinary bungalow” that she “wrapped in ten thousand pounds of polyurethane foam.” At age 52, she resettled on Pierson family territory, living year-round in an artist’s studio across from the family’s Long Island summer house, the upkeep of which she oversaw. Friend recalls her rolling “her own blunts on the porch, pot smoke wreathing her gray topknot.” Norah’s sister changed her name — first calling herself “Reverend Trish,” then Molly Morgan Miller — and never returned to the fold.

As for the impression Tad Friend provides of Theodore Porter Friend — or, himself — it includes an affecting remembrance of his freshman advisor at Harvard, an orotund epicure who shepherded him into the Lampoon; too much about his ten-year on-again, off-again affair with an Italian heiress; and nothing at all about his intellectual formation — not a single recollection of an ecstatic experience with a book, and not one anecdote related to his long tenure at The New Yorker, where he is a staff writer.

Friend might make the case that his undergraduate education and his job aren’t part of this particular story, but I caught myself using his own cultural theories as a lens for understanding the book’s omissions, its flaws. “Visible striving or seriousness of purpose is unWASP because it suggests that you aren’t yet at — haven’t always been at — the top,” he writes. WASPs are, he reports, masters of “the trick of effortlessness . . . the loosely knotted tie and the feet on the sill.” So, Harvard and The New Yorker: yes, they happened, but what’s the big deal?

WASPs are “circumspect,” according to Friend, but he isn’t so circumspect as to keep from exposing himself and his family in this memoir, or of writing about his mother, an emotionally distant woman who imposed upon her children afternoon naps until they were “twelve, thirteen, amazingly old” to keep her house “free of traffic.” She is the dominant — but also most elusive — figure in this story, and her death in 2003 inspired Friend to write the book.

Friend remembers “building the internal WASP rheostat, the dimmer switch on desires” as a child; and of “long[ing]” as an adult for his psychoanalyst to “reach inside” and “rip” it out, which he compares to the moment in the Chronicles of Narnia in which Aslan “gouges off” Eustace’s “scaly exoskeleton.” One of the pleasures of this book is watching Friend struggle to do this — and come pretty close to succeeding.

Michael Rymer writes about education for the Village Voice and about books for Coldfront Magazine. He lives in the Bronx.

Books mentioned in this review:

Cheerful Money

The Official Preppy Handbook

The Chronicles of Narnia

The Making of Americans