Reviewed:

Reviewed:

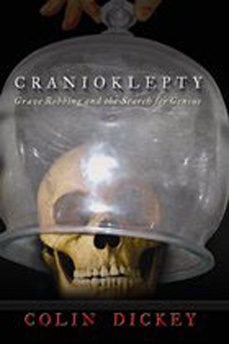

Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius by Colin Dickey

Unbridled Books, 272 pp., $25.95

The early nineteenth century was an especially tumultuous time in global history – the Napoleonic Wars were raging through Europe, the Enlightenment was giving way to modernity, and science was beginning to shed its allegiance to metaphysics and take the form we recognize today. To paraphrase historian Eric Hobsbawm, the long nineteenth century was just starting to get underway, and it came with all the attendant problems and anxieties of a new historical moment. In the midst of all this, Franz Joseph Gall, a young Viennese medical student, was at work developing the “New Science” that was to grip Europe’s imagination and become a critical instrument for registering shifting attitudes towards science, religion and politics. It was called phrenology.

In Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius, Colin Dickey maps the intellectual history of this science and the people who claimed the coveted bones, often using dubious means. In the years after the rise of phrenology, skull robbery became an international sport, and no less than Francisco Goya, Joseph Haydn and Sir Thomas Browne fell victim to the crimes of graveyard thieves. During this period, the sacrilege of upsetting a grave was offset by the belief that the act was an expression of reverence, and so the skulls of many of Europe’s greatest thinkers were clandestinely shuffled around the continent, leaving behind mysteries and loose ends that often lasted for generations.

Phrenology originated in the latter decades of the eighteenth century under Gall, a neuroanatomist whose scientific legacy was redeemed by the discovery of localization – the notion that different parts of the brain control various aspects of our minds and bodies. At phrenology’s core was the belief that personality – whether that of a genius or a madman – could be explained by the skull’s physical characteristics. “To the phrenologist,” Dickey writes, “the skull had its own landscape, where valleys and ridges told a secret story, a hidden territory to be unearthed. Like a geologist reading a strata of rock, a phrenologist could unravel a decades-old history in the contours of a cleaned skull.” Convinced of the correlation between mental capacity and physical appearance, Gall was very much a product of his time, his work making literal the Enlightenment desire to bridge sight and knowledge.

Cranioklepty opens upon a curious scene: It’s 1820, and Viennese soldiers have entered the home of Joseph Carl Rosenbaum, a clerk to Prince Esterhazy and an old friend of composer Joseph Haydn. They find Rosenbaum’s wife in bed, and reluctant to disturb her, leave. On the orders of Esterhazy, the soldiers were looking for something they had recently discovered missing – Haydn’s skull. As it turns out, the skull was hidden in bed with Rosenbaum’s wife and it would be another thirty-two years before it was returned to the public domain. When it did reappear, it was in the hands of Carl von Rokitansky, a rising star among a new generation of anatomists beginning to tinker with Gall’s teachings.

As collecting became popularized, the unearthed skulls of intellectual celebrities proliferated – at one point, there were two attributed to Swedish polymath Emanuel Swedenborg – and scientists were obliged to come up with new ways to test authenticity. This contributed to the rise of craniometrics – the science of extrapolating “truths” from cranial measurements and averages. In the 1890s, as craniometry provided a flimsy intellectual framework for racism, the brain replaced the skull as the defining feature of humanity, and the brains of famous artists and writers were enlisted to prove the superiority of the white European male. With an average brain weighing 1,400 grams, Lord Byron’s tipped the scale at more than 1,800, while Russian writer Ivan Turgenev’s was a formidable 2,012. These statistics were trotted out as proof of the link between genius and brain weight. The growing camaraderie between ideology and scientific method was largely why, over a sixty-year span from the early 1800s onward, “phrenology moved from a theory to a science to an art and finally to a sideshow.” Ultimately, as Dickey says, it would come to be remembered as “one of the most egregious pseudosciences of the nineteenth century.”

Phrenology took hold in the U.S. in the years preceding the Civil War, as Americans searched for a balm to relieve the country’s deepening divides. “Transcendentalists, abolitionists, hydrotherapy advocates, antilacing societies . . . teetotalers, and vegetarians – all lined up to promote their causes,” Dickey writes. “[P]hrenology took them all in and made them part of its grand scheme.” As phrenologists joined the ranks of snake-oil salesmen, consumers who paid to have their skulls read would receive charts rating their personality traits, with a typical examination gauging levels of Adhesiveness, Concentrativeness, Sublimity and Marvelousness, among other vital qualities. These practices were notoriously suspect, and a famous anecdote has Mark Twain visiting the Fowler brothers’ Phrenological Cabinet in Manhattan on two separate occasions. The first time, he went undercover in street clothes, and was told that an oversized “caution bump” had prevented him from accomplishing anything in life. The second time, he wore his signature white suit, introduced himself as Mark Twain, and was promptly told that he possessed the “loftiest bump of humor [Fowler] had ever encountered in his life-long experience!” The final blow came with the 1911 publication of Ambrose Bierce’s satirical Devil’s Dictionary, in which phrenology was immortalized as “the science of picking the pocket through the scalp.”

While Dickey occasionally gets bogged down in all the historical specifics of bizarre coincidences and serendipity – at some points juggling enough characters to rival a Russian novel – it’s easy to see how this was hard to resist. Under the loose theme of grave robbery, the book constructs a deft intellectual history of the period across disciplines and geography. Grave robbery is one of the great themes of human history, Dickey says, and one that retains its relevance in contemporary times. In February of this year, descendants of the Apache chief Geronimo sued Yale’s secret Skull and Bones Society for the warrior’s skull, alleging it was stolen years before by Prescott Bush – President George W. Bush’s grandfather. More recently, grave robbery has given way to online “ghosting,” or stealing the identities of people who are not widely known to be dead. Science may no longer be based on stolen skulls, but as Cranioklepty suggests, people may never concede to let sleeping graves lie.

Jessica Loudis is a Brooklyn-based writer and media junkie. She currently works as a news aggregator for Slate, and is an associate editor at Conjunctions.

Mentioned in this review:

Cranioklepty: Grave Robbing and the Search for Genius

The Devil’s Dictionary