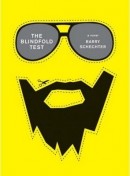

Every Thursday (or in this case, Friday) on the blog brings a post about a paperback book. This might be a book originally published in hardcover or — as with this week’s subject — being published for the first time in paperback.

Jeffrey Parker, the protagonist of Barry Schechter’s debut novel, The Blindfold Test

Jeffrey Parker, the protagonist of Barry Schechter’s debut novel, The Blindfold Test, says, “It’s one of the conventions of sanity that you allow plenty of room for coincidence in your misfortunes.” But Parker has learned that his particular life of misfortune — a stymied academic career, a girlfriend who refuses to commit because he’s “unobservant,” and a host of other happenings (his hair is briefly, inexplicably set on fire while riding the El) — may not be coincidence at all.

In his office at Skokie Valley Community College one day, Parker notices an old acquaintance named Steve Dobbs waiting for him in the hall. Dobbs is the editor of a National Enquirer-like newspaper called The Exhibitionist, and he’s come to educate Parker: Nestled among headlines like “Hitler’s Brain Found in Bus Station,” ten percent of the paper’s stories are actually true. And Parker’s life is going to be the subject of an upcoming article — one of the ten percent. The book is set in the early ’80s, and Parker’s brief association with anti-war activities years ago — tepid attendance at rallies, a couple of editorials for the school paper — got the attention of the government, which then decided to make the rest of his life an unspectacular failure. (The novel takes COINTELPRO as its foundation in reality, an FBI program that, from 1956-1971, investigated dissidence in the U.S. It imagines, from there, that the FBI farmed out some of its activities to everyday crazies who would be given the task of harassing marks.)

In this satire of paranoia, Schechter also adds to the mix: an alleged group of veterans who wear clumsy disguises and protest the government’s indifference to their facial disfigurement; a shadowy organization called Tolerance Management that studies “how much crap people will take” (they’re responsible for things like how long you wait in line at the bank); and a group of academics that are either offering Parker a legitimate job or trying to kill him.

Schechter’s characters frequently say dry, faux-noir things like, “You might say he works for the government — depending on how you define ‘works’ and ‘government’ and ‘the.’” He does an impressive job of maintaining an appropriately light touch while investigating the serious philosophical problem of how we know the truth about any of the forces that influence our lives. Parker wrestles with whether to believe in the conspiracy: “. . . since things had gone awry routinely for most of his adult life, he’d barely had a standard by which to judge himself unlucky — having no more sense of the norm than would, say, a crash-test dummy.”

The problem is the plot. Parker explains to a friend that, “The conspiracy gets pretty hazy around the edges. . .” I’ll say. While sending up the Pynchonian world view, Schechter also has to rely on it to drive the novel forward, and it’s not really up to the task. A long stretch of the novel’s second half leads up to an unbelievable (even by satire’s standards) and ultimately disappointing rally of the veterans group and its fellow disgruntled citizens. As with many more straight-faced fictions about paranoia, the details become increasingly unlikely and unsatisfying. But within the baggy novel that doesn’t quite cohere is a shorter, playful and thought-provoking book about how — and whether — we accept our fate.