Reviewed:

Reviewed:

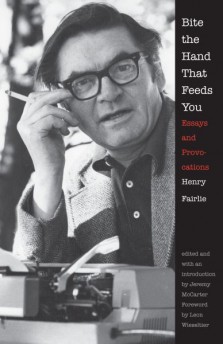

Bite the Hand That Feeds You: Essays and Provocations by Henry Fairlie

Yale University Press, 368 pp., $30.00

Journalists and other writers of nonfiction frequently make lofty claims for the essay’s status as literature. Some refrain from grand pronouncements but still compose essays with a compositional deliberation that aspires to something beyond reportage or argument alone. Henry Fairlie may belong in the latter, quieter group, but he sought to elevate the essay as surely as more vocal proponents of the form. If art is not the word he would have used to describe the sort of pieces gathered by editor Jeremy McCarter in Bite the Hand That Feeds You: Essays and Provocations, that’s because Fairlie believed he was dealing mainly with something of even greater importance: politics. But his evident concern for language, for storytelling and individual style, make him a member of the club that includes Arthur Krystal, Clive James and George Orwell.

“In the right hands,” essays can be “a species of literature,” Krystal wrote in The Half-Life of an American Essayist. James esteems essays so much that he says “a writer is posturing if he calls himself an essayist.” He explains that the pieces in his book As of This Writing (which are called “essential essays” in the collection’s subtitle) began as literary journalism, which he proclaims is “a branch of humanism” and “must be pursued for its own sake,” just as others have said about art. Like Krystal, James believes criticism can have “permanent literary value.” In “Why I Write,” Orwell expressed his hope “to make political writing an art.” Fairlie more modestly says “the essayist is really taking an idea (and his words) for a walk.”

The London-born Fairlie is credited with introducing the term “the Establishment” to describe “the whole matrix of official and social relations within which power is exercised.” In a 1968 piece for The New Yorker, “Evolution of a Term,” Fairlie attempted his own version of Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language.” Fairlie worried about “how imprecise are many of the terms we now use in discussing politics.”

Despite the gaping political differences between Orwell (who wrote “for democratic Socialism”) and Fairlie (“I am a Conservative”), they did share certain ways of thinking. Like Orwell, Fairlie believed writers should write because they have something to say. As Orwell explained in “Why I Write,” he did not sit at his desk and say to himself, “I am going to produce a work of art.” Instead, he wrote because he wanted to make or dispute a point. He took partisanship as his starting place and wrote to challenge the lies of his opponents. Fairlie similarly relished disagreement. In fact, he believed politics absolutely required it. “The truth is that politics does not exist apart from opposition, the opposition of interests and ideas.” Or, as he wrote with Orwellian bluntness: “Politics is too important to be left to the prissy.”

Fairlie’s attentiveness to language and appreciation for stories show that an artistic impulse motivated him as much as it motivated Orwell, whatever he said to the contrary. He explicitly stated his interest in “language and attitudes.” He bemoaned euphemism. He believed in the value of handwritten letters and in the revelatory power of “small anecdotes.” He wrote at length to explain the meanings and nuances of particular words (though this sometimes devolved into the regrettable student-paper maneuver of looking for support in dictionaries, as if their definitions bolstered his arguments). He thought “it is important to know that our presidents understand what literature and ideas are” and he respected British prime minister Winston Churchill for being a reader and a skillful speaker. He worried about the decline of presidential campaign oratory, which no longer offered “the unexpected word” to energize listeners.

Bite the Hand That Feeds You, the title Fairlie chose for a memoir he never completed, reflects his willingness to attack his profession in general and individual peers in particular. He excoriated journalists who lack commitment. He said he didn’t care what position anyone on the political beat took, but he thought it essential that a reporter make choices: “he is worthless unless he cares enough to allow his passion to inform his judgment, his beliefs to discipline his observations.” A “lack of impassioned conviction,” Fairlie contended, can render a writer “worthless to the point of professional fraudulence.” He demonstrated this adamancy when he surveyed the work of Randolph Bourne, a frequent contributor to The New Republic (and thus a predecessor to Fairlie) who died in 1918 at the age of 32. Bourne argued that the United States should have remained neutral in World War I; he especially disapproved of intellectuals collaborating with the military-industrial complex. Fairlie disagreed with Bourne’s conclusions, but admired his “unyielding intellectual commitment.” Bourne was “the most independent, defiant, thoughtful, courageous exemplar of his profession” and a writer who “met even his easy allies with his criticism.” Fairlie’s unyielding and colorful condemnations of fellow journalists – such as Walter Cronkite for “ineffable glibness”; George Will for “a conceit (in both senses) and an ill-mannered use of what looks suspiciously like a little learning”; H.L. Mencken for writing “like a brewer”; and Robert Novak and Rowland Evans for only reporting on “everything in the political world which is unglorious, unmajestic, unlovely” – suggests he might have been trying to also describe himself when assessing Bourne’s best qualities.

Fairlie regarded politics as a higher realm than art – or just about anything else. In a 1976 New Republic essay on the spavined state of political journalism, he said “the one realm in our existence which has released us to contend with the tyrannies of every other realm that matters to us – not least the economic realm of mere survival – is the world of politics. It is not in an art gallery, not in a church, not on a stock exchange, not even in bed, that man is whole. It is at the ballot box.”

For Fairlie, the primacy of politics set limits on what a critic may justifiably do: “He may criticize an individual politician; he has no right to diminish the political function” (as he said Novak and Evans do). He compared the political journalist to an art critic, who can criticize a particular artist but must not denigrate art itself.

Despite his commitment to linguistic precision and politically committed journalism, Fairlie’s personal views were difficult to pin down, despite his elucidation of key terms. He outlined characteristics separating the conservative from the Tory, “who may be allies, but … are not the same creatures.” He said that a Tory believes in strong central government and detests capitalism. He absolutely despised Ronald Reagan and his supporters, whom he absurdly likened to Nazis in a lazy jab flicked when his passion overwhelmed his discipline. “The conservative can all too easily drift into a morally bankrupt and intellectually shallow defense of those who have it made and those who are on the make,” he asserted. He sometimes labeled himself a Tory, but as one willing “to celebrate the American empire.” He often proudly applied the conservative label to his chest, but he adored Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Fairlie celebrated FDR’s “willingness to try anything,” which he believed made the president the quintessential U.S. citizen, since this readiness defines the American character. He moved to the U.S. in the mid-1960s, and in explaining his devotion to his new home, he could be reduced to clichéd and awkward phrasing (“It’s the first time I’ve felt free”; “here one may be being remade”). In contrast, a short piece like “Migration,” about his travels around his chosen country, said fresh volumes about why he loved it. (“Do you know where your bulletin board is made? No. But you can drive into a tiny town in northeast Indiana, and there they make bulletin boards. How satisfying to make something so useful.”)

His strengths were best displayed when he focused on closely observed experiences, as in “The Importance of Bathtubs.” He claimed never to have encountered showers until visiting America, and found that methods of cleanliness revealed key aspects of a people’s character: “If America took the time for the ritual [of taking baths], there would be far less need for all the artificial and expensive rituals of the ‘human potential’ and ‘self-actualization’ therapies that now abound,” he mused. “Only a nation that showers instead of taking baths would have to pay money in order to be taught how to meditate and relax.”

As a collection of pieces written from the mid-1950s to 1990 (when Fairlie died) and not intended to be bound together, Bite the Hand That Feeds You reveals some of the shortcuts and shortcomings of a working journalist. Fairlie had an off-putting tendency to quote himself. He reproduced passages from a New Republic piece in another magazine. He inserted lines from his book The Kennedy Promise in an essay and directly referred to the book in two others, once quoting a review that commended his “wisdom.” He admired his contrast between ordinary people and “the extraordinary people who are always wanting to do extraordinary things to us” well enough to put it in a 1958 Spectator column and an Encounter essay five years later. He recycled the observation that Americans receive great quantities of mail but few personal letters. He more than once voiced his Tory’s concern about the supremacy of “the economic realm” by commenting that a nation’s culture cannot be brought to us “by a grant from Mobil Oil.”

Leon Wieseltier, a former colleague at The New Republic, says Fairlie wrote “when journalism existed in some relation to literature” – as if that bond were ever severed. As writers like Orwell before him, and Krystal, James and countless others after him show, that period Wieseltier claims occurred “in recent antiquity” neither began nor ended with Fairlie’s portion of the twentieth century. Even if not every essay in Bite the Hand That Feeds You can be judged a masterpiece, Fairlie certainly did his part to continue the living tradition of political writing as art.

John G. Rodwan, Jr.’s work has appeared in The Oregonian, Open Letters and The Brooklyn Rail, among other publications. He lives in Portland, Oregon.

Mentioned in this review:

Bite the Hand That Feeds You

The Half-Life of an American Essayist

As of This Writing

The Kennedy Promise