Reviewed:

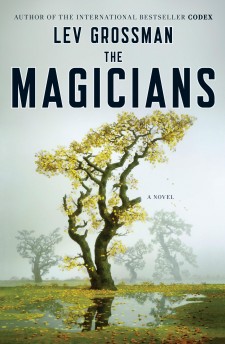

The Magicians by Lev Grossman

Viking, 416 pp., $26.95

The study of magic is not a science, it is not an art, and it is not a religion. Magic is a craft. When we do magic, we do not wish and we do not pray. We rely upon our will and our knowledge and our skill to make a specific change to the world.

So begins the college career of Quentin Coldwater. The school, as you might imagine, is not Harvard, but Brakebills College for Magical Pedagogy. It’s found in upstate New York, concealed behind an array of high-powered spells that render it invisible to all but wizards. The ne plus ultra of magical colleges, Brakebills features a student body that includes “half the Intel Science Talent Search winners and Scripps Spelling Bee champions in the country.” Its entrance exam starts off with a few “fancy differential geometry [questions] and linear algebra proofs.” After that, it starts to get hard.

The intense curriculum includes Middle English, Latin and Old High Dutch as starting points, and soon students are made to learn Estonian, Aramaic and Old Church Slavonic. The physical demands are equally severe; to learn to cast even a simple spell, Quentin must spend hours practicing a series of “hideously complex finger and voice exercises,” which force him to do things like “mov[e] the middle and pinky fingers on both hands independently.”

The intense curriculum includes Middle English, Latin and Old High Dutch as starting points, and soon students are made to learn Estonian, Aramaic and Old Church Slavonic. The physical demands are equally severe; to learn to cast even a simple spell, Quentin must spend hours practicing a series of “hideously complex finger and voice exercises,” which force him to do things like “mov[e] the middle and pinky fingers on both hands independently.”

In other words, this isn’t Hogwarts. (It’s hard to imagine that exact phrase wasn’t used during the pitch meeting for this book.) If the Harry Potter books are about what it’s like to wake up one day and find that you’re a wizard, The Magicians is about what it’s like to wake up every day for ten years and struggle to learn to be a wizard.

As a teacher explains, “This process will be long and painful and humiliating.” He doesn’t exaggerate. By the time he’s graduated, Quentin has been punched in the face, temporarily deprived of the ability to speak, tattooed with a spell that implants a living cacodemon into the small of his back, dropped naked in the middle of Antarctica (he uses magic to stay alive), and introduced to an interdimensional entity named “The Beast,” who freezes an entire classroom in time, strolls casually around the room, and then, almost as an afterthought, devours one of Quentin’s friends alive.

Despite the trials he endures, Quentin is generally happy at Brakebills. The learning consumes him, driving away occasional bouts of unhappiness. As he nears graduation, though, he begins to fall prey to a “creeping infectious sense of futility” that has been with him for his entire life. Unable to draw fulfillment from either schoolwork or a budding relationship with another student, he finds himself “looking around frantically for . . . a way out . . . waiting for some grand adventure.” He moves to New York, surrendering to a life of drugs, alcohol and semi-promiscuous sex; but none of it helps. He’s still miserable.

All this ends when a classmate stumbles upon an enchanted button, the use of which will transport its users to any of a near-infinite number of parallel realities. It’s the adventure Quentin’s been waiting for, and in a few weeks he finds himself leading an expedition of fellow wizards to the magical land of Fillory. The setting for a series of children’s books published in the 1930s, Fillory is essentially Narnia. A lifelong fan of the books, Quentin has grown up fantasizing about being able to visit, or even to live there. It’s his Utopia, a place where, as he says, “things mattered in a way they didn’t in this world. Happiness was a real, actual, achievable possibility. It came when you called. Or no, it never left you in the first place.”

The actual Fillory, as attentive readers will anticipate, turns out to have about as much in common with Quentin’s romanticized ideal as Hogwarts does with Brakebills. Having a fireball shoot from your hands into the body of an oncoming foe may seem thrilling in a book, but the reality of watching another person burned alive is a traumatic and deeply painful experience.

Magic in this world is not just about wonder; it’s also about pain. To its credit, The Magicians is rich in both. Engaging, exciting — and yes, enchanting — The Magicians does what all magic should. It transplants us to another world, a place with laws we can intuit but not understand. It holds us in its thrall and then, just as we begin to see a deeper pattern, it fades away. We hope that what we’ve just experienced was something more than a trick. But even if it was just a trick, we don’t complain. It was a good one.

Tim Lake is a writer in Los Angeles.

Mentioned in this review: