Reviewed:

Reviewed:

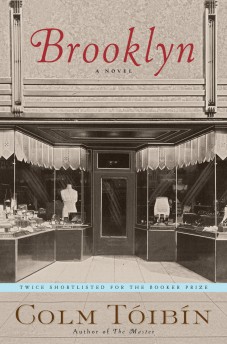

Brooklyn by Colm Tóibín

Scribner, 272 pp., $25.00

It’s a small miracle — and a happy one — that Colm Tóibín named a novel Brooklyn before one of the countless young writers who have colonized the borough over the past decade. (Actually, it was a photo finish. Joanna Smith Rakoff had been calling her novel Brooklyn, but changed it to A Fortunate Age after Tóibín planted his flag.) So instead of the story we may have gotten — and have gotten, with different titles — about pharmaceutical-induced contentment, precocious magical realism or a group photo of millennial ennui, Tóibín reclaims the borough from the hipsters and gives it back to the aspiring immigrants.

Early in his previous novel, The Master, a profoundly impressive imagining of the life of Henry James, we see James standing beneath the window of a man he wishes to visit but can’t bring himself to visit. As he stares upward:

He wondered now if these hours were not the truest he had ever lived. The most accurate comparison he could find was with a smooth, hopeful, hushed sea journey, an interlude suspended between two countries, standing there as though floating, knowing that one step would be a step into the impossible, the vast unknown.

Brooklyn opts for a literal sea journey into the unknown, though it’s anything but smooth and hushed. It’s taken by Eilis Lacey, a plain, smart young woman from Enniscorthy, Ireland, who has trouble finding work there in the early 1950s. Soon after the opening scenes have established her loving, lightly teasing relationship with her mother and sister (the three share a modest house), she’s told that a local priest can arrange a job and lodging for her in New York. Eilis, in her early 20s, “had always presumed that she would live in the town all her life, as her mother had done, knowing everyone, having the same friends and neighbours, the same routines in the same streets.” But with little external sign of struggle, she boards a ship to America. Her third-class ticket buys her an epically tossed voyage, with few details spared the reader, who may share her nausea.

Once in New York, Eilis has work but not much else. She dutifully maintains her daily routine with no real spark until an Italian named Tony falls in love with her. She’s hesitant to return his strong feelings, which “made her feel that she would have to accept that this was the only life she was going to have, a life spent away from home.”

Tóibín’s work tends to send critics running to find synonyms for “understated,” for good reason. The raves for The Master regularly included adjectives like “unshowy,” “nuanced,” “subtle,” and “quiet.” If The Master was quiet, Brooklyn is damn near mute. In it, Tóibín boils down his normally austere style even further to a striking aridity, with very few conspicuous writerly moves of any kind on display. There’s very little sense, in fact, of a teller’s perspective at all.

A paragraph representative of the tone:

Her mother woke her saying it was almost teatime. She had slept, she guessed, for almost six hours and wanted nothing more than to go back to sleep. Her mother told her that there was hot water in case she wanted a bath. She opened her suitcases and began to hang clothes in the wardrobe and store other things in the chest of drawers. She found a summer dress that did not seem to be too wrinkled and a cardigan and clean underwear and a pair of flat shoes.

When Tóibín does make his presence more strongly felt, it shows up as a lovely flash, as when he describes Eilis struggling to adapt to her new surroundings: “…the torment was strange, it was all in her mind, it was like the arrival of night if you knew that you would never see anything in daylight again.” But he employs these effects far less frequently than, say, William Trevor, another brilliant minimalist, or even the Colm Tóibín of The Master.

The fact that James’ inner life was drawn in the previous novel with such a greater amount of detail than Eilis’ seems less a result of the legendary novelist’s intelligence or the numerous sources Tóibín had at hand to help conjure him than an intentional scheme. There is something purposely archetypal, almost fable-like about Brooklyn, which gives it charm while simultaneously limiting the more complicated pleasures that you can almost feel Tóibín withholding. It comes as little surprise that he originally thought Brooklyn would be a novella between longer projects. “I wanted to do something much simpler,” he has said, “and see if I could get a greater effect from it, which was simply almost like you get a piece of paper and pencil and you drew a single line.”

It’s true that Tóibín’s straight lines are more accomplished than most authors’ curlicues, particularly in the book’s opening and closing acts, when Eilis is in Ireland. If Tóibín struggles to bring Brooklyn to the technicolor life it deserves, he effortlessly invokes his home country. This is less a matter of detail than atmosphere. There’s not much weight behind the portrait of Brooklyn, which makes excursions to local landmarks like Ebbets Field feel more cartoonish than was likely intended. Tóibín simply seems less self-conscious on his own soil. Eilis would no doubt relate. Enniscorthy was dull, but it was hers. In Brooklyn, she feels the weight of “the long night alone in a room that had nothing to do with her.” It’s homesickness, and the impossibility of properly conveying its contours to others and even yourself, that’s best captured in Brooklyn. After Eilis returns to Enniscorthy (whether she’ll stay for good becomes a dramatic question), we see the difficulty of feeling truly at home anywhere once you’ve been at home elsewhere.

John Williams is the editor of The Second Pass.

Books mentioned in this review: