Reviewed:

Reviewed:

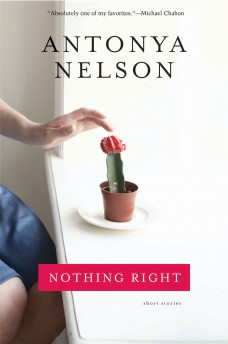

Nothing Right: Short Stories by Antonya Nelson

Bloomsbury, 304 pp., $25.00

Antonya Nelson has an eye for imperfection. In this exquisite story collection, her ninth work of fiction, she lavishes her attention on deeply flawed characters. For the most part their flaws are not the aching, poetic ones of much literary fiction, but the rather mundane, irritable ones of actual people.

In the story “Obo,” a moping, lying grad student finagles herself an invitation to Christmas with the family of her professor’s wife so that she might creepily linger around the woman with whom she has become obsessed. In “Falsetto,” the protagonist’s boyfriend mangles every attempt to console her during a family tragedy, and she bristles at even his best intentions, leaving the reader with little sympathy for either person. These men and women disdain their spouses, resent their children and ignore their dogs. One character observes of her psychiatrist husband’s reaction to their daughter, “Teenage Kay-Kay had overtaxed him – this despite the fact that he made his living hearing how people were routinely failed by their loved ones, and how relentlessly they failed themselves. In the office, he used the when-did-you-stop-beating-your-wife approach, asking not if but how often they fell short.” Nelson’s stories ask the same question.

The most prominent theme in the aptly titled Nothing Right is disappointment. Born in 1961, Nelson grew up on the heels of the baby boomers, and watching members of that generation believe they could be anything they wanted, only to slowly realize that ruling the world was tougher than it appeared, seems to have had a profound effect on her fiction. Many of these stories involve an event in life that should be seminal and effect profound change, but instead fizzles into a merely temporary disruption. When a teenage girl absconds with her toddler cousin overnight, all four of the parents fear disaster, only to feel strangely let down when the incident ends up too minor to shake them from their sleepy, imperfect lives.

Affairs are just as ineffectual in producing change for Nelson’s cast. In “Biodegradable,” Mimi, married with three children, embarks on a passionate tryst with a man living in his grandmother’s charmingly quirky country home. Mimi is ready for dramatics. As the affair rages, “she felt whatever it was between them intensify, like a song that abruptly dips into a more resonant, lower key, like a body of water that grows suddenly deeper, colder, stiller yet more treacherous.” But when her lover casually puts the house up for sale, the relationship dissolves almost instantly.

Nelson has a way of aligning the expectations of her reader with those of her characters — the lookout for the life-altering event, the climactic sentence — and consistently subverting them. Even those characters whose lives are on the cusp of falling apart or who face genuine tragedy are forced to get through, to find a way of quietly persisting. In “DWI,” Sadie, married mother of a young son, learns that her longtime flame and family friend, the reckless and possibly suicidal Sebastian, has died in an Easter Sunday car accident. “Like Sadie, Sebastian had had the overwhelming, bottomless-pit-variety appetite for more: higher speed, extra stimulation, supplemental love. There were people who could live a sober life, and then there were those who couldn’t, who needed the additional thrilling torque. It was a bad appetite, and without relief.” Because the depth of their relationship remains a secret, Sadie has to withstand the bombs exploding inside her and demonstrate an appropriately modest amount of grief.

Nelson has a sure grasp of life’s uncontrived rhythm. Perhaps the most accomplished section in Nothing Right is a two-page description of a large family’s movements through and around the home over a holiday. “There was always someone studying the interior of the refrigerator or washing his hands or waiting expectantly for something to happen. Groceries came in; trash went out.” The short-story writer is perpetually confronted with the difficulty of forcing ordinary life into satisfying narrative. Nelson, with her clear understanding of this problem and her graceful ability to use it to her advantage, remains at the top of the genre.

Katie Henderson is a freelance writer and editor. She has a BA from Columbia University and is currently completing an MA at New York University, both in English literature. Her reviews have appeared on examiner.com.

Books mentioned in this review: