Last year, I pointed to an essay about the work of Gilbert Rogin, who wrote comic fiction that was praised by John Updike and John Cheever, among others. Now, his two novels are being republished

Last year, I pointed to an essay about the work of Gilbert Rogin, who wrote comic fiction that was praised by John Updike and John Cheever, among others. Now, his two novels are being republished, and the New York Observer has an entertaining profile of him: “[I]n the spring of 1980, Mr. Rogin, 50 years old and seemingly at the top of his game, submitted a new short story to Roger Angell, the baseball essayist who was then chief fiction editor at The New Yorker. Mr. Angell passed, telling Mr. Rogin, ‘You’re repeating yourself.’ [. . .] That Mr. Rogin took Mr. Angell’s criticism personally should come as no surprise. Told that the Russians were boycotting the 1984 Olympics, Mr. Rogin carped, ‘Why are they doing this to me?’ ” . . . Ian Crouch takes a look at Ladbrokes’ odds for this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature. William Trevor sits at 45-1. Trevor is 82 years old. I hope he has many years left to win the award, but one never knows. I don’t care about awards, generally, but if Trevor never wins it I’ll be kind of ticked off. . . . After a time of rough sailing, Harper’s is showing signs of renewed life. The magazine has hired Zadie Smith to write its monthly New Books column. (She replaces the very good Ben Moser, who will continue writing for Harper’s.) . . . Gay Talese sits down for a substantive interview with James Mustich. . . . On October 5 in Park Slope, as part of the lecture series Adult Education, Jim Hanas will celebrate the release of his short story collection, and various presenters will speak about “The Future of the Book.” . . . The Library of America shares Virginia Woolf’s opinion of Henry James’ conversational skills, and notes 10 recent novels that use James as a fictional character. . . . Mark Athitakis points to a Dale Peck review, originally meant to be published in The Atlantic, praising Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day. . . . Sharmila Sen imagines translations as the wives of original texts: “If fidelity represents a certain kind of stasis, then the beauty of a translation lies in the very promise of infidelities it can inspire.” . . . Last but not least, a belated happy birthday to The Casual Optimist, the smart books/design blog that turned two last week.

Archives, September, 2010

Thursday, September 30th, 2010

In the Ether

Monday, September 27th, 2010

The Cherry & the Pit(s)

A continuing series that highlights books recently acquired by publishing houses for future release. Each post features a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

This feature’s been away for a bit, so two pits for you today:

The Cherry:

Holly George-Warren’s A Man Called Destruction: The Life & Music of Alex Chilton from the Box Tops to Big Star to Backdoor Man, a biography of the iconoclastic and influential musician drawn from interviews conducted with Chilton before his March 2010 death as well as with his friends, family, and music colleagues.

The Pits:

Elsa Watson’s Dog Days, in which a small, town cafe owner is struck by lightning and switches bodies with the lost dog following her, then must struggle with her new canine instincts to overcome her fear of dogs and learn how to live and love with the carefree perspective of a dog.

Nina Benneton’s Compulsively Mr. Darcy, about a germ-phobic philanthropist William Darcy who meets granola, infectious-disease Doctor Bennet during one crazy trip to Vietnam to adopt a trendy orphan.

Friday, September 24th, 2010

Keeping the Books

After David Markson died earlier this year, many books from his personal collection started showing up in random places on the shelves of The Strand, New York’s great repository of used (and new) books. There was a bit of uproar at the time (if there can be a bit of uproar) from those who wondered how it could possibly happen that an acclaimed American writer’s books ended up in the hands of various Strand diggers rather than a protected home, perhaps in the academy. No one seemed interested in investigating whether this was simply Markson’s desire. But Craig Fehrman has:

In David Markson’s case, the easiest explanation for why his books ended up at The Strand is that he wanted them to. Markson, who lived near the bookstore, would stop by three or four times a week. The Strand, in turn, hosted his book signings and maintained a table of his books, and Markson’s daughter, Johanna, says he frequently told her in his final years to take his books to The Strand. “He said they’d take good care of us,” she says.

That comes from a broader piece Fehrman wrote about authors’ libraries for the Boston Globe, in which he considers the fate of personal collections when famous authors die:

Most people might imagine that authors’ libraries matter—that scholars and readers should care what books authors read, what they thought about them, what they scribbled in the margins. But far more libraries get dispersed than saved. In fact, David Markson can now take his place in a long and distinguished line of writers whose personal libraries were quickly, casually broken down. Herman Melville’s books? One bookstore bought an assortment for $120, then scrapped the theological titles for paper. Stephen Crane’s? His widow died a brothel madam, and her estate (and his books) were auctioned off on the steps of a Florida courthouse. Ernest Hemingway’s? To this day, all 9,000 titles remain trapped in his Cuban villa.

I’m not sure I agree that libraries are inherently interesting or revealing. I’m not a famous writer, but I’m a big reader, and my shelves are home to several books I didn’t love, many books I haven’t read, and a few books temporarily on loan from friends. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say that I’m not sure they are so interesting that an author like Markson shouldn’t be allowed to give them to his favorite shop down the block. Fehrman writes about the efforts—noble or crazy, depending on your perspective—of some scholars to retroactively compose a list of all the books an author owned: “The effort and ingenuity behind these lists can be astounding, as scholars will sift through diaries, receipts, even old library call slips. A good example is Alan Gribben’s Mark Twain’s Library: A Reconstruction, which runs to two volumes and took nine years to complete.”

On his own blog, Fehrman expanded on his article with an interesting post about Melville, and about the strategies employed by university archivists looking for a big catch.

Wednesday, September 22nd, 2010

Paris Review Interview Bonanza

The four collections of Paris Review interviews published by Picador in recent years are beautiful books worth owning. (I wrote about the series and the fourth volume here. Oh, and actually wrote about earlier volumes at another venue, here and here and here.) Now, as part of new editor Lorin Stein’s regime, all of the Review’s interviews are available online.

The four collections of Paris Review interviews published by Picador in recent years are beautiful books worth owning. (I wrote about the series and the fourth volume here. Oh, and actually wrote about earlier volumes at another venue, here and here and here.) Now, as part of new editor Lorin Stein’s regime, all of the Review’s interviews are available online.

Browsing through the subjects by last name, I get the distinct sense that I’ll be losing many, many hours to this archive, though the negative connotations of “losing” are not at all apt here. Just three that I will be diving into soon: Michiko Kakutani (and the magazine’s editors) interviewing Woody Allen. John Sullivan talking to Guy Davenport. And George Plimpton and the great John Gregory Dunne (pictured above), who waste no time getting started, beginning like this:

Plimpton: Your work is populated with the most extraordinary grotesqueries—nutty nuns, midgets, whores of the most breathtaking abilities and appetites. Do you know all these characters?

Dunne: Certainly I knew the nuns. You couldn’t go to a parochial school in the 1940s and not know them. They were like concentration-camp guards. They all seemed to have rulers and they hit you across the knuckles with them. The joke at St. Joseph’s Cathedral School in Hartford, Connecticut, where I grew up, was that the nuns would hit you until you bled and then hit you for bleeding. Having said that, I should also say they were great teachers. As a matter of fact, the best of my formal education came from the nuns at St. Joseph’s and from the monks at Portsmouth Priory, a Benedictine boarding school in Rhode Island where I spent my junior and senior years of high school. The nuns taught me basic reading, writing, and arithmetic; the monks taught me how to think, how to question, even to question Catholicism in order to better understand it. The nuns and the monks were far more valuable to me than my four years at Princeton. I’m not a practicing Catholic, but one thing you never lose from a Catholic education is a sense of sin and the conviction that the taint on the human condition is the natural order.

Tuesday, September 21st, 2010

The Beat

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

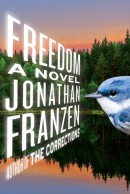

Charles Baxter reviews Jonathan Franzen’s latest. Finally, someone keeps this book from slipping under the radar. (”Freedom operates as a kind of morality play in which all the major players are drawn toward actions they should not perform and objects they either cannot or should not possess. . . . [Its] ambition is to be the sort of novel that sums up an age and that gets everything into it, a heroic and desperate project.”) . . . James Marcus reviews Robert Fox’s We Were There, which compiles firsthand accounts of how people experienced the 20th century. Marcus thinks the emphasis on World War II crowds out other events, but finds the book “valuable” in the end: “It vividly illustrates a general principle of such first-person testimonies: they are most interesting when they surprise us, when some element of human perversity creeps into the picture and messes with our expectations.” . . . “Told in a voice that echoes the magic cadences of Toni Morrison or the folk wisdom of Zora Neale Hurston’s collected oral histories,” Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns is, according to Lynell George, a “lush, expansive and harrowing history of the decades-long exodus of blacks, which became known as the Great Migration . . . when black people in the South disappeared, often under the cover of night, frequently leaving their sharecropper’s tools in the fields, their future plans and whereabouts a mystery to those they left behind.” . . . Susan Casey has written about great white sharks, and her new book returns to the ocean to look at surfers and extremely large waves. Matt Robinson says the book is “a sort of surfing safari, part educational (Ms. Casey interviews oceanographers, physicists, marine insurers) and part explorational—a search for something to gawp at.” . . . With Cultures of War, Pulitzer-winning historian John Dower has written a “thought-provoking, scholarly and deeply polemical book” about the lessons to be learned from Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, 9/11, and the Iraq war.

Charles Baxter reviews Jonathan Franzen’s latest. Finally, someone keeps this book from slipping under the radar. (”Freedom operates as a kind of morality play in which all the major players are drawn toward actions they should not perform and objects they either cannot or should not possess. . . . [Its] ambition is to be the sort of novel that sums up an age and that gets everything into it, a heroic and desperate project.”) . . . James Marcus reviews Robert Fox’s We Were There, which compiles firsthand accounts of how people experienced the 20th century. Marcus thinks the emphasis on World War II crowds out other events, but finds the book “valuable” in the end: “It vividly illustrates a general principle of such first-person testimonies: they are most interesting when they surprise us, when some element of human perversity creeps into the picture and messes with our expectations.” . . . “Told in a voice that echoes the magic cadences of Toni Morrison or the folk wisdom of Zora Neale Hurston’s collected oral histories,” Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns is, according to Lynell George, a “lush, expansive and harrowing history of the decades-long exodus of blacks, which became known as the Great Migration . . . when black people in the South disappeared, often under the cover of night, frequently leaving their sharecropper’s tools in the fields, their future plans and whereabouts a mystery to those they left behind.” . . . Susan Casey has written about great white sharks, and her new book returns to the ocean to look at surfers and extremely large waves. Matt Robinson says the book is “a sort of surfing safari, part educational (Ms. Casey interviews oceanographers, physicists, marine insurers) and part explorational—a search for something to gawp at.” . . . With Cultures of War, Pulitzer-winning historian John Dower has written a “thought-provoking, scholarly and deeply polemical book” about the lessons to be learned from Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, 9/11, and the Iraq war.

Thursday, September 16th, 2010

When One Translation Is Not Enough

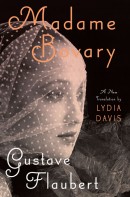

The Paris Review’s blog has a new look, to coincide with the first issue published under the guidance of Lorin Stein, and it also has a guest post by Lydia Davis, who will be writing on the site over the next two weeks about “the tasks and sins of the translator.” Davis’ new translation of Madame Bovary

The Paris Review’s blog has a new look, to coincide with the first issue published under the guidance of Lorin Stein, and it also has a guest post by Lydia Davis, who will be writing on the site over the next two weeks about “the tasks and sins of the translator.” Davis’ new translation of Madame Bovary is out later this month.

Wise people like to say, wisely: Every generation needs a new translation. It sounds good, but I believe it isn’t necessarily so: If a translation is as fine as it can be, it may match the original in timelessness, too—it may deserve to endure. In fact, it may endure even if it is not all it should be in style and faithfulness. The C. K. Scott Moncrieff translation of most of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (which he called, to Proust’s distress, Remembrance of Things Past) was written in an Edwardian English more dated than Proust’s own prose, and it departed consistently from the French original. Yet it had such conviction, on its own terms, and was so well written, if you liked a certain florid style, that it prevailed without competition for eighty years. (There was also, of course, the problem of finding a single individual to do a new translation of a 3,000-page book—an individual who wouldn’t die before finishing it, as Scott Moncrieff had. This problem Penguin solved at last by appointing a group to do it.)

Thursday, September 16th, 2010

Walnut What?

I keep reading things about Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom that make me extremely wary of it. Today’s wary-making fact: It features an indie rock band called Walnut Surprise. This is one of those small details that might actually mean a lot. Franzen has consciously positioned himself as the foremost chronicler of How We Live Now (and reaped significant rewards for the positioning), but I remain unconvinced that he knows How We Live Now. There are, of course, thousands of bands with terrible names out there. Whether any of those names are as uniquely terrible as Walnut Surprise is a debate for another time. From what I understand—and yes, I should just read the book, which I plan to do—the name and the band are not meant for purely satirical purposes. In other words, the band is taken seriously (up to a point), etc. The name Walnut Surprise, in my humble opinion, for a band that is hailed by almost anyone, is a minor indication that the person who came up with that name is Out of Touch.

I keep reading things about Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom that make me extremely wary of it. Today’s wary-making fact: It features an indie rock band called Walnut Surprise. This is one of those small details that might actually mean a lot. Franzen has consciously positioned himself as the foremost chronicler of How We Live Now (and reaped significant rewards for the positioning), but I remain unconvinced that he knows How We Live Now. There are, of course, thousands of bands with terrible names out there. Whether any of those names are as uniquely terrible as Walnut Surprise is a debate for another time. From what I understand—and yes, I should just read the book, which I plan to do—the name and the band are not meant for purely satirical purposes. In other words, the band is taken seriously (up to a point), etc. The name Walnut Surprise, in my humble opinion, for a band that is hailed by almost anyone, is a minor indication that the person who came up with that name is Out of Touch.

Tuesday, September 14th, 2010

Equal Before the Lens

This post was written by Jacob Silverman.

This post was written by Jacob Silverman.

How do you like your irony? The answer may determine how you feel about Created Equal, Mark Laita’s book of 105 photographic diptychs. If you don’t mind irony that comes in the form of a wink, a knowing tilt of the head, a sly gesture tending toward the obvious, then you’ll probably appreciate the juxtapositions that Laita makes with these 210 portraits culled from a decade of photographing Americans throughout the lower 48 states.

Most of the photos are black-and-white, a dark muslin backdrop and diffuse lighting allowing for a full view of the subjects, most of whom face the camera directly, usually bearing an expression just this side of angry or bemused. Below each photograph are the subject’s name, a descriptive label (usually his or her profession), and a date and location. There are some recurring types: sex workers, pimps, cops, convicts, priests and nuns, gamblers, models and bodybuilders, the mentally disabled (including several identified as inbred). Taken on their own, the photos are aesthetically interesting and well composed, but Laita’s project is more provocative for how he labels and arranges his subjects.

The title of the book begs us to draw equivalences between those depicted. The captions help us along, recasting subjects as something entirely different from what they appear. The man in a space suit is obviously an astronaut (confirmed by the underlying descriptor), yet we have no idea who the casually dressed, middle-aged woman on the adjacent page is until we read that she’s an alien abductee (self-proclaimed, I assume). It’s a clever juxtaposition on Laita’s part, but it also points to a limitation of his scheme: appreciating these diptychs often hinges on the reductive labels applied to them.

Laita’s approach is one of enforced harmony. The juggler and the air traffic controller, presumably paired because both keep track of complicated patterns in the air. A ballerina and a boxer, telling us something about physical grace. The stock traders and the demolition derby crew, varieties of destruction. In a few inspired cases, the labels are almost irrelevant. The stripper who occupies both sides of a diptych—naked in one, clothed and holding a grocery bag in the other—is striking because she’s almost unrecognizable from one photograph to the next but both images reflect fundamental aspects of her identity. In another set, a boy holding a jar of fireflies is paired with a moonshiner, each grasping a glass jar that holds something precious to its owner.

Laita’s approach is one of enforced harmony. The juggler and the air traffic controller, presumably paired because both keep track of complicated patterns in the air. A ballerina and a boxer, telling us something about physical grace. The stock traders and the demolition derby crew, varieties of destruction. In a few inspired cases, the labels are almost irrelevant. The stripper who occupies both sides of a diptych—naked in one, clothed and holding a grocery bag in the other—is striking because she’s almost unrecognizable from one photograph to the next but both images reflect fundamental aspects of her identity. In another set, a boy holding a jar of fireflies is paired with a moonshiner, each grasping a glass jar that holds something precious to its owner.

Many of these diptychs, though, are screamingly obvious—a real estate agent and a homeless woman, a bank robber and sheriff’s deputies, a black Baptist minister and Ku Klux Klan members—while others are too insistent on their connections, like the bug-eyed man with his mail-order wife set against a movie producer with his much younger wife. There’s a sense of abridgment here, of too much interpretation being done for us. The man wearing a “warden” badge is called an “executioner,” but he could, of course, be identified as a prison warden—a label that’s probably more accurate and certainly less political. (He, by the way, is paired with a fortuneteller.)

While Created Equal’s introduction, written by Ingrid Sischy, tells us that Laita spent less than 10 minutes with some of his subjects, the notes section at the end of the book provides some illuminating details. One of the pimps was shot and killed a week after his photograph was taken; one male cross-dresser was new to the lifestyle and felt “excited about interacting with someone as a woman;” the “only thing that bothers” the executioner “is that [his work] doesn’t bother” him; the Latino dishwasher, wearing a hairnet and appearing close to tears, works in a “small 24-hour deli in Manhattan, where none of the employees speak the same language and everyone seems to hate each other, including the customers.” There are such endnotes for perhaps a third of the photographs, and they’re fascinating. They indicate that Laita, when he takes the time to listen to his subjects, is able to craft deceptively emotive scenes that gesture at something larger than themselves–like an Amy Hempel story visualized. I appreciate the humanistic spirit of a book that attempts to call us all equal (especially when many of these people are culled from society’s margins), and that doesn’t glamorize its subjects, but it also seems restricted by the form Laita has chosen. I look forward to a future work that builds on his demonstrated ability to capture compelling subjects, while presenting them through a less constricted lens.

While Created Equal’s introduction, written by Ingrid Sischy, tells us that Laita spent less than 10 minutes with some of his subjects, the notes section at the end of the book provides some illuminating details. One of the pimps was shot and killed a week after his photograph was taken; one male cross-dresser was new to the lifestyle and felt “excited about interacting with someone as a woman;” the “only thing that bothers” the executioner “is that [his work] doesn’t bother” him; the Latino dishwasher, wearing a hairnet and appearing close to tears, works in a “small 24-hour deli in Manhattan, where none of the employees speak the same language and everyone seems to hate each other, including the customers.” There are such endnotes for perhaps a third of the photographs, and they’re fascinating. They indicate that Laita, when he takes the time to listen to his subjects, is able to craft deceptively emotive scenes that gesture at something larger than themselves–like an Amy Hempel story visualized. I appreciate the humanistic spirit of a book that attempts to call us all equal (especially when many of these people are culled from society’s margins), and that doesn’t glamorize its subjects, but it also seems restricted by the form Laita has chosen. I look forward to a future work that builds on his demonstrated ability to capture compelling subjects, while presenting them through a less constricted lens.

Jacob Silverman is a contributing online editor for the Virginia Quarterly Review. His work has appeared in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, The National, The Daily Beast, and many other publications.

Friday, September 10th, 2010

100 Issues Young

A belated congratulations to Michael Schaub and Jessa Crispin at Bookslut, who published the site’s 100th issue earlier this week. A remarkable achievement.

Quieter than I expected around here this week, for personal reasons (nothing bad). Full speed next week: new reviews in Circulating, the return of regular blogging, and a general shaking off of summer and full embrace of a busy fall.

Wednesday, September 8th, 2010

The Paranoid Style

New on the Backlist this week, Tim Crimmins writes at length about America’s Founding Fathers, Britain’s radical Whigs, and the Tea Party. He begins the piece by citing Richard Hofstadter’s “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” an essay that first appeared in the November 1964 issue of Harper’s. The entire thing is available online. It begins:

New on the Backlist this week, Tim Crimmins writes at length about America’s Founding Fathers, Britain’s radical Whigs, and the Tea Party. He begins the piece by citing Richard Hofstadter’s “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” an essay that first appeared in the November 1964 issue of Harper’s. The entire thing is available online. It begins:

American politics has often been an arena for angry minds. In recent years we have seen angry minds at work mainly among extreme right-wingers, who have now demonstrated in the Goldwater movement how much political leverage can be got out of the animosities and passions of a small minority. But behind this I believe there is a style of mind that is far from new and that is not necessarily right-wing. I call it the paranoid style simply because no other word adequately evokes the sense of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy that I have in mind. In using the expression “paranoid style” I am not speaking in a clinical sense, but borrowing a clinical term for other purposes. I have neither the competence nor the desire to classify any figures of the past or present as certifiable lunatics. In fact, the idea of the paranoid style as a force in politics would have little contemporary relevance or historical value if it were applied only to men with profoundly disturbed minds. It is the use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant.

Of course this term is pejorative, and it is meant to be; the paranoid style has a greater affinity for bad causes than good. But nothing really prevents a sound program or demand from being advocated in the paranoid style. Style has more to do with the way in which ideas are believed than with the truth or falsity of their content. I am interested here in getting at our political psychology through our political rhetoric. The paranoid style is an old and recurrent phenomenon in our public life which has been frequently linked with movements of suspicious discontent.

Friday, September 3rd, 2010

A Fledgling Sci-Fi Collection

That last post inspired me to take a quick look around my own bookshelves. I’d say the apartment currently houses between 800 and 900 books (his and hers), and I have a few hundred more in storage. I’m always adding to that number, and not always in ways that make a ton of sense. For instance, I will very occasionally—maybe once every few years—buy a sci-fi book, despite the fact that the last sci-fi book I finished was probably something by Isaac Asimov when I was something like 13 years old. This is not to impugn sci-fi, but just to say I never had much of a natural taste for it. A few years back, I bought Ender’s Game

That last post inspired me to take a quick look around my own bookshelves. I’d say the apartment currently houses between 800 and 900 books (his and hers), and I have a few hundred more in storage. I’m always adding to that number, and not always in ways that make a ton of sense. For instance, I will very occasionally—maybe once every few years—buy a sci-fi book, despite the fact that the last sci-fi book I finished was probably something by Isaac Asimov when I was something like 13 years old. This is not to impugn sci-fi, but just to say I never had much of a natural taste for it. A few years back, I bought Ender’s Game, widely considered a classic of the genre. It remains perched on a bottom shelf.

Last night, I bought a copy of Marsbound by Joe Haldeman, having recently read a review that piqued my interest. Perhaps after I collect a few more titles—and there are plenty of guides for help—I’ll get around to reading them.

Friday, September 3rd, 2010

“I don’t want to read them. I just want them around.”

Scott David Herman notes that his book collection has passed a milestone:

As of last week, it grieves me to say, our book collection has finally broken a thousand. The tally as of this writing is one thousand and three. Some are hers, some are mine, some are ours. Regarding the mine-and-ours: Don’t ask me how many of them I’ve read or will read or will even ever crack open and flip through in search of something, I beg you. Don’t ask me how well I remember or understand the ones I have read. Just don’t go there. The answers will reflect poorly on all involved. The shame of the high books-bought-to-books-read ratio is of course comfortingly widespread among us of the book-nerd persuasion. Let’s just round down and say I haven’t read any of them. I don’t want to read them. I just want them around. I require them in my home. And I must have more.

(Via Levi Stahl)

Thursday, September 2nd, 2010

Something Must Be Wrong

At the magazine of Wabash College, Jason Boog writes about losing his job and finding some measure of solace in the work of 1930s novelists. It begins:

I lost my job in December 2008, unemployed at the beginning of the longest, coldest winter I can remember in New York City.

Up until then, everything had been going swimmingly: I was a staff writer at an investigative reporting publication, taught an undergraduate journalism class, and proposed to my girlfriend in a fairytale forest along the Hudson River. Suddenly, I had to tell my friends, relatives, and students how I had failed.

Out of everything I read during those gloomy months, I found the most comfort in Maxwell Bodenheim—an author who lost everything during the Great Depression. In 1934, he wrote: “There’s something wrong with this world all right, but I can’t put my finger on it. . . . Something must be wrong when a fellow can’t get a decent wage, can’t tell when he’s going to be fired, can’t look forward to any promise of happiness. Something is rotten somewhere.”

Thursday, September 2nd, 2010

And the Winners Are

Congratulations to readers Merlin Brittenham and Dan (who blogs at Imagined Icebergs), who, respectively, won a copy of The Varieties of Religious Experience and The Heart of William James.

There will be more giveaways soon, probably related to the idea of older favorites. Stay tuned.

Wednesday, September 1st, 2010

In the Ether

Mark Pilkington recommends 10 books about UFOs that are “either informative, entertaining, puzzling or all three at once.” . . . Lorin Stein discusses the art of the Paris Review’s famous interviews, and offers a peek at a few future subjects. . . . Penguin launches a new monthly radio series, “The Literary Life,” with guests Rosanne Cash, Maile Meloy, Doug Dorst, and Sloane Crosley. . . . Independent book sellers recommend 40 books from independent publishers that they will be recommending to customers over the next few months. . . . Andrew Pettegree is interviewed about the advent of printed books. (“There’s quite a little similarity in the first generation of print with the dot-com boom and bust of the ’90s.”) . . . Sad news to long-live-print folks like myself: The next edition of the Oxford English Dictionary will be available only in e-form. . . . Jonathan Lethem talks about leaving his beloved Brooklyn for California. . . . I’m going to start reading the work of Thomas Bernhard soon; perhaps as soon as this afternoon. Scott Bryan Wilson offers a checklist of his work. . . . Rick Gekoski on “how to be a good literary loser.” . . . Ian Hocking, novelist, writes movingly about the decision to stop writing fiction. (“Someone wrote – [Stephen] King again, I think – that a writer is a person who will write no matter what. In other words, if you lock them up in a cell without pen or pencil, they’ll write on the wall in their own blood. I didn’t believe that when I read it and I don’t believe it now. Even Stephen King comes to a point when the blood dries up.”)

Mark Pilkington recommends 10 books about UFOs that are “either informative, entertaining, puzzling or all three at once.” . . . Lorin Stein discusses the art of the Paris Review’s famous interviews, and offers a peek at a few future subjects. . . . Penguin launches a new monthly radio series, “The Literary Life,” with guests Rosanne Cash, Maile Meloy, Doug Dorst, and Sloane Crosley. . . . Independent book sellers recommend 40 books from independent publishers that they will be recommending to customers over the next few months. . . . Andrew Pettegree is interviewed about the advent of printed books. (“There’s quite a little similarity in the first generation of print with the dot-com boom and bust of the ’90s.”) . . . Sad news to long-live-print folks like myself: The next edition of the Oxford English Dictionary will be available only in e-form. . . . Jonathan Lethem talks about leaving his beloved Brooklyn for California. . . . I’m going to start reading the work of Thomas Bernhard soon; perhaps as soon as this afternoon. Scott Bryan Wilson offers a checklist of his work. . . . Rick Gekoski on “how to be a good literary loser.” . . . Ian Hocking, novelist, writes movingly about the decision to stop writing fiction. (“Someone wrote – [Stephen] King again, I think – that a writer is a person who will write no matter what. In other words, if you lock them up in a cell without pen or pencil, they’ll write on the wall in their own blood. I didn’t believe that when I read it and I don’t believe it now. Even Stephen King comes to a point when the blood dries up.”)