Archives, September, 2009

Wednesday, September 30th, 2009

I love Kay Ryan’s poems. They’re simultaneously playful and profound. The Washington Post interviewed the U.S. Poet Laureate during last weekend’s National Book Festival. She was asked if she ever gets recognized in public now:

I do! I was at a festival recently at Yosemite, and I was standing in line to use the bathroom. This was up in the Tuolumne Meadows, and the people said, You go first! And I said, Oh I couldn’t possibly. They said, You must! There was quite a line, and I said, This is great! And then at the reading, I said: Auden said that poetry makes nothing happen, but that’s not true — I got cuts in the bathroom line.

Wednesday, September 30th, 2009

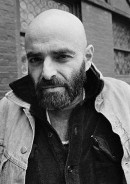

Jon Fasman — novelist, Second Pass contributor and good friend — recently sat down to tea with James Ellroy for The Economist. They discussed Blood’s a Rover, Ellroy’s latest, and other subjects.

Starting at the two-minute mark, Jon draws forth a very candid response about the book’s dedication. The rest is filled with Ellroy’s confidence (“this is a book that has it all”), and his thoughts about combining real and invented history (and whether he cares about acknowledging which is which), how much he outlines and how much he improvises, and “vicariously dig(ging) . . . voodoo alcohol.” Enjoy:

Tuesday, September 29th, 2009

Monday, September 28th, 2009

The second and concluding part in a look at notable books being published next month:

Invisible

Invisible by Paul Auster

by Paul Auster

Three narrators tell a story spanning 40 years in Auster’s latest, about which Kirkus said, “More than a return to form, this might be Auster’s best novel yet.” Oct. 27

The Book of Genesis Illustrated by R. Crumb

In a project guaranteed (designed?) to generate controversy, the gonzo cartoonist tackles the gonzo Old Testament. Oct. 19

Look at the Birdie by Kurt Vonnegut

by Kurt Vonnegut

Fourteen previously unpublished stories by the legendary writer. Oct. 20

The Museum of Innocence by Orhan Pamuk

by Orhan Pamuk

The Nobel Prize winner’s latest is set in 1970s Istanbul, and concerns a wealthy scion torn between his equally prominent bride-to-be and an average woman he passionately loves. Oct. 20

Reading Jesus: A Writer’s Encounter with the Gospels by Mary Gordon

by Mary Gordon

Feeling alienated from many other Christians, Gordon closely reads the Gospels to decide if she has “invented a Jesus to fulfill my own wishes.” Oct. 27

The Book of Basketball: The NBA According to The Sports Guy by Bill Simmons The massively popular ESPN writer and hoops junkie produces a thorough (and thoroughly opinionated, I’m sure) account of pro basketball’s past, present and future.

by Bill Simmons The massively popular ESPN writer and hoops junkie produces a thorough (and thoroughly opinionated, I’m sure) account of pro basketball’s past, present and future.

Cowboys Full: The Story of Poker by James McManus

by James McManus

The best-selling author of Positively Fifth Street offers a comprehensive history of poker, from its global antecedents to today’s wildly popularized game. Oct. 27

The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire that Saved America by Timothy Egan

by Timothy Egan

An account of a 1910 forest fire, the largest in American history, and the president and volunteers who tried to stop it. Oct. 19

The American Civil War: A Military History by John Keegan

by John Keegan

The esteemed military historian turns his sharp eye to America’s defining struggle. Oct. 20

Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 by Gordon S. Wood

by Gordon S. Wood

The latest addition to the essential Oxford History of the United States series. Oct. 26

The Queen Mother: The Official Biography by William Shawcross

by William Shawcross

The “definitive” biography (it better be, at 1,120 pages) of Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon. Oct. 27

Eating the Dinosaur by Chuck Klosterman

by Chuck Klosterman

A new collection of pop-culture overanalysis by the voice of a generation (for better or worse). Oct. 20

Last Night in Twisted River by John Irving

by John Irving

The mega-best-selling author’s sprawling twelfth novel starts in 1954 at a logging settlement in New Hampshire. Oct. 27

Ayn Rand and the World She Made by Anne C. Heller

by Anne C. Heller

A biography of the woman who launched a million libertarians. Oct. 27

Liver by Will Self

by Will Self

Self’s new fiction takes the form of four long stories set in and around London’s Plantation Club. Oct. 27

The Lexicographer’s Dilemma: The Evolution of “Proper” English, from Shakespeare to South Park by Jack Lynch

by Jack Lynch

Charting the evolution of our language and the fascinating obsessives who have played a part — Jonathan Swift, Samuel Johnson, Noah Webster, et al. Oct. 27

Revolution 1989 by Victor Sebestyen

by Victor Sebestyen

A new account of the collapse of the Soviet Union’s European empire. Oct. 27

Monday, September 28th, 2009

The Millions wrapped up its list of the 21st century’s best novels last week with The Corrections at numero uno. Eek. Not a choice I would make — or sanction, or even learn of without gasping — but all’s fair in democracy, I suppose. The list of participants in the poll was impressive (I snuck in somehow).

Also of interest is the comparison of the panel’s top 20 to the top 20 of Millions readers. The readers, I think, were collectively smarter than the panel about Gilead by Marilynne Robinson and Atonement by Ian McEwan, ranking them higher. They also recognized Richard Russo (Empire Falls) and Michael Chabon (The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay), which the panel didn’t. (I’m a big Russo fan, but think he published his best work in the 20th century; and I didn’t love Chabon’s novel, but given how many others seemed to, I’m pretty shocked it didn’t make the panel’s top 20.)

The full top five I submitted, for what it’s worth: Gilead, Atonement, It’s All Right Now by Charles Chadwick, The Master by Colm Tóibín, and The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint by Brady Udall.

Monday, September 28th, 2009

To complement our review of Tad Friend’s Cheerful Money (up today in Circulating), here’s an interview with the author over at the site of his employer, The New Yorker. Among other things, he discusses the odd notion that his children may not consider themselves WASPs:

I guess I’d like Walker and Addie to feel they always have a broad set of choices about how to live—where, and in what manner, and toward what ends—while at the same time I would feel sad if they entirely repudiated the way I grew up. Because that would feel, to a great extent, like a repudiation of me. I know this is a mixed message, but I comfort myself that sending mixed messages is what parenting is all about.

Friday, September 25th, 2009

The fall preview in these parts continues (a review of September can be found here, if you’re interested) with a look at several books slated for October release. Part two will be up on Monday. (Two late-September releases are included below.)

Chicago: A Biography

Chicago: A Biography by Dominic A. Pacyga

by Dominic A. Pacyga

This history, written by a Chicago native, charts the city from the explorations of Joliet and Marquette in 1673 to the current day, with a particular focus on ordinary people and their stories. Oct. 1

The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis

At 750 pages, this volume contains all of Davis’ highly acclaimed, often experimental short (sometimes very short) fiction. Sept. 29

Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife by Francine Prose

by Francine Prose

A wide-ranging examination of the classic document, in which Prose, according to Publishers Weekly, argues that the diary was “a consciously crafted work of literature rather than the spontaneous outpourings of a teenager, and offers evidence that Frank scrupulously revised her work shortly before her arrest and intended to publish it after the war.” Sept. 29

Manhood for Amateurs: The Pleasures and Regrets of a Husband, Father, and Son by Michael Chabon

by Michael Chabon

Linked autobiographical essays by the bestselling, prize-winning novelist. Oct. 6

The Simpsons: An Uncensored, Unauthorized History by John Ortved

by John Ortved

I can’t wait for this one. Oct. 13

The Children’s Book by A.S. Byatt

by A.S. Byatt

Byatt’s latest follows two artistic British families from 1895 through the end of World War I. Oct. 6

The Casebook of Victor Frankenstein by Peter Ackroyd

by Peter Ackroyd

A period piece about the friendship between Frankenstein and the poet Shelley. Oct. 6

Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

by Hilary Mantel

Mantle’s tenth novel, set in 16th-century England, concerns the relationship between Thomas Cromwell and Henry VIII. Already published in the UK, there it’s been called Mantel’s “most humane and bewitching” work yet. Oct. 13

Looking for Calvin and Hobbes: The Unconventional Story of Bill Watterson and His Revolutionary Comic Strip by Nevin Martell

by Nevin Martell

The first October release about a great comic strip. Oct. 1

Bloom County: Complete Library, Vol. 1 by Berkeley Breathed

by Berkeley Breathed

The second. Oct. 6

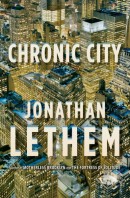

Chronic City by Jonathan Lethem

by Jonathan Lethem

Lethem’s latest is a tale of paranoia about a young Manhattanite and his girlfriend, who happens to be trapped in outer space. Oct. 13

Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original by Robin Kelley

by Robin Kelley

Self-explanatory, no? Oct. 6

Inventory: 16 Films Featuring Manic Pixie Dream Girls, 10 Great Songs Nearly Ruined by Saxophone, and 100 More Obsessively Specific Pop-Culture Lists by The A.V. Club

by The A.V. Club

The Onion’s sister publication collects its pop-culture lists and adds new ones to the mix, with contributors like John Hodgman, Amy Sedaris and Patton Oswalt. Foreword by Chuck Klosterman. Oct. 13

The Red Book by Carl Jung

by Carl Jung

See much more about this here. Oct. 7

Bright-sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America by Barbara Ehrenreich

by Barbara Ehrenreich

From the press materials: “Ehrenreich traces the strange career of our sunny outlook from its origins as a marginal nineteenth-century healing technique to its enshrinement as a dominant, almost mandatory, cultural attitude.” Oct. 13

Friday, September 25th, 2009

The other day, browsing at the local B&N, I came across an alarmingly thick novel written by Ralph Nader, and now the New Yorker takes a closer look at this development. The book — Nader eschews the term novel for it; prefers the hilariously oxymoronic “a practical utopia” — is called Only the Super-Rich Can Save Us!

The other day, browsing at the local B&N, I came across an alarmingly thick novel written by Ralph Nader, and now the New Yorker takes a closer look at this development. The book — Nader eschews the term novel for it; prefers the hilariously oxymoronic “a practical utopia” — is called Only the Super-Rich Can Save Us! (The exclamation point is a part of the official title and “super-rich” is even underlined on the front cover, leading me to believe the novel — sorry, the practical utopia — may have been ghostwritten by an 11-year-old girl.)

(The exclamation point is a part of the official title and “super-rich” is even underlined on the front cover, leading me to believe the novel — sorry, the practical utopia — may have been ghostwritten by an 11-year-old girl.)

This is, as far as I can tell, the final step in Nader morphing into the left’s Ayn Rand. For instance, the naming department: Not cowed by the difficulty of beating Rand’s Ragnar Danneskjöld, Nader’s stand-in for the real world’s already-goofily-named Grover Norquist is “a conservative evil genius named Brovar Dortwist.” (The magazine deserves a major prize for coaxing this from Norquist: “I have warm fuzzies for [Nader] on a number of levels.”) But surely Nader can’t match Rand’s imagination when it comes to outlandish blueprints for ideological wish fulfillment? Well, check out this sentence fragment: “Yoko Ono, who in the book invents a logo called Seventh-Generation Eye that causes millions of people suddenly to shed their political apathy . . .”

Oh, my. The book is ranked 166 on Amazon as I write this, so it appears people are actually reading it.

Friday, September 25th, 2009

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

This rave about a six-volume, illustrated edition of Vincent van Gogh’s letters makes me want to start saving money for it. (“Intimate, compelling and comprehensive, the letters make a serious formal biography both redundant and impossible.”) . . . Speaking of illustrated, a look at “a glorious new full-color visual history of the USSR” that draws from “one of the world’s most admired collections of Russian posters, photographs and graphics.” . . . Natasha Wimmer believes there “is room for a resurgence, even a resurrection” of the work of Mercè Rodoreda. Her books included The Time of the Doves. (Wimmer: “many thousands of books have been written about the experience of the Spanish Civil War, but none has equaled it.”) . . . Ross Simonini reviews The Book of Jokes, a novel by pop-music experimentalist Momus. (“In the way that Robert Coover and John Barth reinterpreted fairy tales and American urban myths in their fiction, Momus uses the folklore of humor. [T]he book is less a single narrative than what it says it is: a novel-in-jokes, an episodic account of the joke’s ability to grab attention and flip expectation.”) . . . Scott Simon says that half a century after it was published, Allen Drury’s novel Advise and Consent “remains the definitive Washington tale.” . . . Andrew O’Hagan takes a long, absorbing look at Samuel Johnson.

This rave about a six-volume, illustrated edition of Vincent van Gogh’s letters makes me want to start saving money for it. (“Intimate, compelling and comprehensive, the letters make a serious formal biography both redundant and impossible.”) . . . Speaking of illustrated, a look at “a glorious new full-color visual history of the USSR” that draws from “one of the world’s most admired collections of Russian posters, photographs and graphics.” . . . Natasha Wimmer believes there “is room for a resurgence, even a resurrection” of the work of Mercè Rodoreda. Her books included The Time of the Doves. (Wimmer: “many thousands of books have been written about the experience of the Spanish Civil War, but none has equaled it.”) . . . Ross Simonini reviews The Book of Jokes, a novel by pop-music experimentalist Momus. (“In the way that Robert Coover and John Barth reinterpreted fairy tales and American urban myths in their fiction, Momus uses the folklore of humor. [T]he book is less a single narrative than what it says it is: a novel-in-jokes, an episodic account of the joke’s ability to grab attention and flip expectation.”) . . . Scott Simon says that half a century after it was published, Allen Drury’s novel Advise and Consent “remains the definitive Washington tale.” . . . Andrew O’Hagan takes a long, absorbing look at Samuel Johnson.

Friday, September 25th, 2009

Every Thursday on the blog (hey, it’s still Thursday in parts of the country) brings a post about a paperback book.

A few weeks ago, the New York Times profiled Mexican author Mario Bellatín, who has written “a score of novellas” over the past 25 years, but is largely unknown in the U.S. Beauty Salon was first published in 1994, and the English translation — by Kurt Hollander — appeared earlier this year. It’s a 63-page book, on very small pages, literally pocket-sized.

A few weeks ago, the New York Times profiled Mexican author Mario Bellatín, who has written “a score of novellas” over the past 25 years, but is largely unknown in the U.S. Beauty Salon was first published in 1994, and the English translation — by Kurt Hollander — appeared earlier this year. It’s a 63-page book, on very small pages, literally pocket-sized.

The story’s unnamed narrator is a hairdresser whose salon has been converted into “the Terminal,” a place where those dying of a (also unnamed) contagious disease come to spend their last days. In its prime, the shop was decorated with several stunning aquariums, and the owner and two of his employees (all three transvestites) would sneak around the city on sexual adventures. Now, only one tank still holds fish, and it’s so murky that it’s impossible to tell how many are inside. The AIDS-like affliction has spread far and wide.

The book’s epigraph comes from Kawabata Yasunari: “Anything inhumane becomes human over time.” That’s a good indication of what’s to come, in part: a study in how exposure to ceaseless death inures one to it.

Initially, the narrator seems more than detached; he seems to take some kind of perverse pleasure in the suffering of others, as when he describes his preferred brand of patient: “I don’t really know how to describe this state, although it’s something like a total lethargy in which even the possibility of them inquiring about their own health no longer exists. This is the ideal state in which to work.” He selfishly wishes that the dying and their families, who already express their thanks and give the narrator more money than he needs to keep the operation running, would “express their gratitude in a more tangible way.” And then there’s his policy on female patients:

The Terminal underwent a crisis when several women came to ask me to let them die there. They came to the salon in very bad condition. Some were holding small children also ravaged by the disease. I stood firm from the very beginning. The beauty salon had once been dedicated to beautifying women and I wasn’t willing to sacrifice so many years of work. Which is why I never accepted anyone that wasn’t a man, regardless of how much they pleaded.

But when the narrator refers to the first sick person who ever arrived at his door, it is clear his initial attitude was considerably less cold. In that instance:

I remember how we all almost went crazy trying to revive him. We brought in doctors, nurses and herbalists, and we even went to visit some witch doctors. We took up a collection among friends to buy him some very expensive medicine.

Looking back at the young man’s death, he says, “The end was simple. There was no cure. All our efforts were merely vain attempts to ease our conscience.” The story’s lack of specificity makes it clearly intended as a fable of sorts, but in our year of “death panels” there’s easy relevance to be found in the way Bellatín grimly plays with the philosophy of mortality. The narrator briefly mentions the Sisters of Charity, who occasionally show up offering to help, and who he repeatedly turns away:

I imagine how this place would be run by such people, with medicine everywhere, uselessly trying to save lives that were already on death’s list, prolonging suffering under the guise of Christian charity. The worst of it is how hard they would try to demonstrate what a noble sacrifice life is when dedicated to others.

Bellatín is without a part of his right arm, which the critic Francisco Goldman (a friend of the author’s) refers to when he says:

People often say, with a lot of truth to it, that all good fiction writing comes from some wound, out of some distance that needs to be breached between a writer and normalcy. In Mario’s sense, the wound is literal and comes with all kinds of psychological nuance and pain, and seems related to sexuality and desire, the desire for a whole body. One of my favorite aspects of him is this sense that he is writing for all the freaks — either literally freaks or privately and metaphorically, that he really touches us.

It’s a bit of a stretch for Beauty Salon to exist as a stand-alone book. Though it might mirror classics like Camus’ The Plague in its conceit, it’s hardly damning Bellatín to say that his story is slighter in depth as well as length. But read alongside several other of his many novellas, I imagine the power of Beauty Salon’s cold tone and subtler themes would have a greater effect, so I hope the translations keep coming.

Thursday, September 24th, 2009

I’m a very big baseball fan, but I had no idea the Tampa Bay Rays had an outfielder who would feel moved to write this:

I’m a very big baseball fan, but I had no idea the Tampa Bay Rays had an outfielder who would feel moved to write this:

One of my first managers always preached separation from the game for the sake of our own health, and for the sake of our performance. The game can be maddening, and we ought to corner ourselves in this trade only so far. I’m in love with baseball, but eventually my prime will end, and she’ll slowly break my heart. Baseball has remained remarkably impervious to modernity, but is, like any modern industry, highly alienating. I turn to poetry because it is less susceptible to circumstance. I’m not especially touched when a poet deals with a ball game; I’m not especially interested in having one world endear itself to the other.

He also says of Robert Creeley: “He has been my most important poet, because I can take him anywhere, like oranges . . .”

And he wrote a piece for the New York Times about the music players choose to play when they come to bat, which includes these tremendously entertaining thoughts on his own selections:

There was only one song that I would choose for myself, and that was the “Price Is Right” theme. The horns are so brave! . . . In the way of “pump up” music, I used Talib Kweli and the Walkmen, but quickly learned it wasn’t advantageous to feel like I wanted to jump or scream about ex-girlfriends. . . . When I got to the major leagues, I went Motown. My friend asked why, and I said it was a diplomatic selection, that Motown, like Chinese food, is one of the few things people of all sorts can agree upon.

This is almost enough to make me a Rays fan. Almost.

(Via The Morning News)

Thursday, September 24th, 2009

From Nausea

From Nausea by Jean-Paul Sartre:

by Jean-Paul Sartre:

This man was one-ideaed. Nothing more was left in him but bones, dead flesh and Pure Right. A real case of possession, I thought. Once Right has taken hold of a man exorcism cannot drive it out; Jean Parrottin had consecrated his whole life to thinking about his Right: nothing else. Instead of the slight headache I feel coming on each time I visit a museum, he would have felt the painful right of having his temples cared for. It never did to make him think too much, or attract his attention to unpleasant realities, to his possible death, to the sufferings of others. Undoubtedly, on his death bed, at that moment when, ever since Socrates, it has been proper to pronounce certain elevated words, he told his wife, as one of my uncles told his, who had watched beside him for twelve nights, “I do not thank you, Thérèse; you have only done your duty.” When a man gets that far, you have to take your hat off to him.

Wednesday, September 23rd, 2009

The new fall issue of The Paris Review features an interview with James Ellroy. In the excerpt available online, he trashes Raymond Chandler and praises Dashiell Hammett:

The new fall issue of The Paris Review features an interview with James Ellroy. In the excerpt available online, he trashes Raymond Chandler and praises Dashiell Hammett:

Chandler wrote the kind of guy that he wanted to be, Hammett wrote the kind of guy that he was afraid he was. Chandler’s books are incoherent. Hammett’s are coherent. Chandler is all about the wisecracks, the similes, the constant satire, the construction of the knight. Hammett writes about the all-male world of mendacity and greed. Hammett was tremendously important to me.

But what wisecracks and similes! Ellroy also accounts for himself during the years 1965-1975 — a section that is, er, not G-rated — and bemoans the focus of the attention he gets:

I’ve told many journalists that I’ve done time in county jail, that I’ve broken and entered, that I was a voyeur. But I also told them that I spent much more time reading than I ever did stealing and peeping. They never mention that. It’s a lot sexier to write about my mother, her death, my wild youth, and my jail time than it is to say that Ellroy holed up in the library with a bottle of wine and read books.

Tuesday, September 22nd, 2009

Tuesday, September 22nd, 2009

I’ve taken the plunge. The Twitter plunge.

From now on, you can follow The Second Pass at this page. And please, do sign up to officially “follow.” It will make me feel good.

I know the site updates on a somewhat irregular schedule (though those who are paying attention know that certain blog features appear on certain days), so if it’s easier for you to be notified of new material via Twitter, I hope this helps. Mostly, the posts (refusing to call them “tweets” is my remaining form of protest, I suppose) will be links to the site, but there will be occasional random thoughts (I’ll try to keep them bookish), and occasional trivia (like the fact that I’m listening to Bruce Springsteen’s “Jungleland” as I type this; that kind of thing).

Tuesday, September 22nd, 2009

The six finalists for the Best of the National Book Awards Fiction award have been announced. Four of the six are short-story collections — all of them of the “complete” or “collected” variety, which seems a little like cheating. Those four are by John Cheever, William Faulkner, Flannery O’Connor and Eudora Welty. The other two finalists are Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon and Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison.

When I first wrote about this, I (hesitantly) predicted that Invisible Man would win it. Go to the site, vote, and make me a visionary! If you give them your e-mail address, you’re entered in a contest to attend this year’s NBA ceremony in November and spend two nights at a Manhattan hotel.

(Update: I just voted, and they show you the current results. Flannery O’Connor is in the lead with 31% and Ellison is second at 24%. Looks like it will come down to one of those two. Cheever’s bringing up the rear.)

Tuesday, September 22nd, 2009

A lively, beautifully illustrated interview with Paul Buckley, a creative designer at Penguin. (“I found and purchased an image for a difficult book cover project recently just because I decided to google ‘leucistic squirrel’ after I noticed a few in Prospect Park. I have no idea how we all existed before the internet.”) . . . On her lovely new blog, Like Fire, Lisa Peet marvels at Carl Jung’s unearthed “Red Book.” . . . Translator Natasha Wimmer discusses her work on forthcoming Roberto Bolaño novels. And The Millions offers a Bolaño syllabus. . . . Scott Pack alerts us to an upcoming anthology about atheism, pegged to Christmas. The book includes an essay by Duran Duran singer Simon Le Bon about losing his faith. . . . The salvation of books? The death of books? I have a headache. You decide. . . . The great New York Review of Books Classics line is celebrating its 10th anniversary with events now through November. . . . The MacArthur Foundation has announced its annual “genius grants.” This year’s writers are Edwidge Danticat, Deborah Eisenberg and poet Heather McHugh.

A lively, beautifully illustrated interview with Paul Buckley, a creative designer at Penguin. (“I found and purchased an image for a difficult book cover project recently just because I decided to google ‘leucistic squirrel’ after I noticed a few in Prospect Park. I have no idea how we all existed before the internet.”) . . . On her lovely new blog, Like Fire, Lisa Peet marvels at Carl Jung’s unearthed “Red Book.” . . . Translator Natasha Wimmer discusses her work on forthcoming Roberto Bolaño novels. And The Millions offers a Bolaño syllabus. . . . Scott Pack alerts us to an upcoming anthology about atheism, pegged to Christmas. The book includes an essay by Duran Duran singer Simon Le Bon about losing his faith. . . . The salvation of books? The death of books? I have a headache. You decide. . . . The great New York Review of Books Classics line is celebrating its 10th anniversary with events now through November. . . . The MacArthur Foundation has announced its annual “genius grants.” This year’s writers are Edwidge Danticat, Deborah Eisenberg and poet Heather McHugh.

Monday, September 21st, 2009

For five years now, UK blogger extraordinaire Norman Geras has been curating a Writer’s Choice series, in which writers expound on some of their favorite books. Now, he’s put together an index for the entire series. There are well over 200 entries, with contributors including Philip Pullman, Christopher Hitchens and Alain de Botton. Several friends of The Second Pass have added their talents to the mix, so I point you to those in particular: Jon Fasman on his first encounter with Sherlock Holmes; Jason Zinoman on the criticism of Pauline Kael; Jennifer Szalai on an illuminating work of philosophy; Carlene Bauer on Edith Wharton’s House of Mirth; the “Charles” exacta of Bryan Charles on Charles Portis; Edward McPherson on his annual habit of rereading Poe; Robert Westfield on Dostoevsky’s “brilliant comedy of spite,” Notes from Underground; and yours truly on David James Duncan’s The Brothers K.

Monday, September 21st, 2009

Over at The Millions, they’re counting down the top 20 novels since the turn of the millennium. The methodology and a general intro to the project can be found here. I was flattered to be on the list of respondents to their poll, and further honored when they asked me to write the entry for the #20 novel, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. I could argue that this is much too low a spot for it, but democracy has spoken. My take on one of my all-time favorite novels can be read here. (”The book’s modest, carefully planed language and its concern with primary human needs make it timeless, but it’s hard not to also marvel at and appreciate the way it functions as a timely corrective.”)

Over at The Millions, they’re counting down the top 20 novels since the turn of the millennium. The methodology and a general intro to the project can be found here. I was flattered to be on the list of respondents to their poll, and further honored when they asked me to write the entry for the #20 novel, Gilead by Marilynne Robinson. I could argue that this is much too low a spot for it, but democracy has spoken. My take on one of my all-time favorite novels can be read here. (”The book’s modest, carefully planed language and its concern with primary human needs make it timeless, but it’s hard not to also marvel at and appreciate the way it functions as a timely corrective.”)

The feature continues throughout the week, culminating in the appearance of #1 on Friday.

Monday, September 21st, 2009

The Cherry & the Pit feature has been on hiatus because I’m waiting for some particularly tasty cherries, which have been few and far between. But in the meantime, I saw this recent sale:

Sarah Gray’s Wuthering Bites, a retelling of Wuthering Heights in which Heathcliff is a vampire.

Note to the publishing industry: Please. Please. Stop.

Friday, September 18th, 2009

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Caleb Crain reviews Morris Dickstein’s Dancing in the Dark, “a bighearted, rambling new survey of American culture in the nineteen-thirties.” Comparing it to Dickstein’s cultural history of the 1960s, Gates of Eden, Dwight Garner calls Dancing in the Dark “a heavier, slower, more lumbering book, at times a hard-drive-emptying round of plot summaries and historical filler.” . . . Louisa Gilder calls a new biography of eccentric physicist Paul Dirac “a thought-provoking meditation on human achievement, limitations and the relations between the two.” . . . Seed magazine also recommends the Dirac bio (“a tour de force filled with insight and revelation. [A]n unprecedented and gripping view of Dirac not only as a scientist, but also as a human being.”), along with several other recent science books. . . . Dexter Filkins says that Jon Krakauer is a “masterly writer and reporter,” but that his book about the death of Pat Tillman feels padded, at least a hundred pages too long. . . . Steve Almond marvels at recent right-wing bestsellers, “in which the mundane terrors of cultural dislocation are recast as riveting epics of paranoia.”

Caleb Crain reviews Morris Dickstein’s Dancing in the Dark, “a bighearted, rambling new survey of American culture in the nineteen-thirties.” Comparing it to Dickstein’s cultural history of the 1960s, Gates of Eden, Dwight Garner calls Dancing in the Dark “a heavier, slower, more lumbering book, at times a hard-drive-emptying round of plot summaries and historical filler.” . . . Louisa Gilder calls a new biography of eccentric physicist Paul Dirac “a thought-provoking meditation on human achievement, limitations and the relations between the two.” . . . Seed magazine also recommends the Dirac bio (“a tour de force filled with insight and revelation. [A]n unprecedented and gripping view of Dirac not only as a scientist, but also as a human being.”), along with several other recent science books. . . . Dexter Filkins says that Jon Krakauer is a “masterly writer and reporter,” but that his book about the death of Pat Tillman feels padded, at least a hundred pages too long. . . . Steve Almond marvels at recent right-wing bestsellers, “in which the mundane terrors of cultural dislocation are recast as riveting epics of paranoia.”

Thursday, September 17th, 2009

Every Thursday on the blog brings a post about a paperback book.

In his mid-30s, Dennis Covington was feeling depressed. A college English teacher who felt that his job was “minor and absurd,” he yearned for an adventure “in which the risks were real.” He found one. After reporting on the trial of an Alabama preacher who was accused of trying to kill his wife with poisonous snakes, Covington immersed himself in the Appalachian world of holy snake handlers. The resulting book, Salvation on Sand Mountain

In his mid-30s, Dennis Covington was feeling depressed. A college English teacher who felt that his job was “minor and absurd,” he yearned for an adventure “in which the risks were real.” He found one. After reporting on the trial of an Alabama preacher who was accused of trying to kill his wife with poisonous snakes, Covington immersed himself in the Appalachian world of holy snake handlers. The resulting book, Salvation on Sand Mountain , was recently reissued to mark its 15th anniversary.

, was recently reissued to mark its 15th anniversary.

As subcultures go, this one is pretty nuts. The snake handlers believe that the Bible asks a chosen few to take up serpents as a show of faith. When a handler named Brother Clyde is bit on both hands, another church member, Cecil, tells Covington that Clyde hadn’t been fully anointed to handle the creature, and that “You’d have to be crazy to go and pick up a snake like that.”

“Do you know Punkin Brown?” Cecil asked.

I shook my head.

“Brother Punkin is from Newport, Tennessee,” he said. “Now there’s a man who really gets anointed by the Holy Ghost. He’ll get so carried away, he’ll use a rattlesnake to wipe the sweat off his brow.” Cecil paused and glanced around the square. “That brother Clyde, though. He must have been a little mentally ill.”

In a community that draws such lines, there is obviously a lot of unintentional humor to be mined, and Covington does the job, as in this reaction to a woman who describes a hospital visit to him:

“You know, a whole lot of them doctors are against serpent handling.”

I told her I bet they were.

But Covington invites some of this same sarcastic reaction from his readers. On page 196, about 80% of the way through the book, after learning that a handler was bitten by “a four-foot rattler whose fangs went so deep they had to pry the snake off of him,” Covington realizes that “I was in way over my head.”

No kidding, Dennis.

During his research, Covington discovers that his great-great-grandfather was a Methodist preacher in the very parts of Alabama where he’s spending much of his time. (“I have no reason to believe he took up serpents,but I do have reason to believe he was a precursor of those who eventually did.”) With a sense that he’s learning something vital and primordial about himself, Covington is drawn further and further into the handlers’ world (at one point taking up a snake himself), and though he convincingly charts his emotional responses, it’s occasionally difficult to reconcile his smart, skeptical, reportorial side with the leap it must have taken to start feeling truly at home among the handlers.

But the book is both breezy (written in what might be called Smart Magazine style) and engaged with substantive spiritual issues, if that’s not an oxymoron. And it builds to a riveting climactic scene, in which the limits of tolerance and understanding are dramatically reached. In a new afterword, written earlier this year, Covington looks back on the experience and says that he was “taken in by the handlers, but not bamboozled.”

Wednesday, September 16th, 2009

The Guardian’s John Crace, who writes the paper’s “Digested read” column, sits down with the new book by that Brown guy after it’s dropped off by a messenger who’s been followed:

I grabbed the book. “Sign here,” he commanded. Instead I drew a hand, the Hand of Mysteries. The courier stepped back, his face blanched with fear. “So y-y-you’re…” he stammered. “Yes,” I replied. The race against narcolepsy had begun.

Wednesday, September 16th, 2009

The opening sentence of The Emperor of Ice-Cream by Brian Moore:

by Brian Moore:

The Divine Infant of Prague was only eleven inches tall yet heavy enough to break someone’s toes if he fell off the dresser.

Tuesday, September 15th, 2009

Sarah Weinman shares a piece of an “impolite” 1961 interview with Shel Silverstein. The whole interview is worth a read. (Q: “You used to sell hot dogs when the Chicago Cubs were playing, and the White Sox. What did you learn about people from this experience?” A: “I learned they like mustard. . . .”) . . . I don’t know much (of any depth) about Jim Carroll, who died last week, but I was transfixed by this clip of him talking about his youthful basketball career and basketball generally. . . . A gift idea for the book-loving baseball fans in your life: author jerseys. I particularly like Bartleby and Poe (with the raven on front, not the heart). I might have to make it out to the launch party at Freebird Books in Brooklyn on Sunday to get my hands on one. Paper Cuts likes the shirts, too. . . . I learned about John Gall because the various book-design sites I visit would often write about his work. Now, Gall has his own blog, which I’ve added to the Links page. . . . Tonight in New York, the European Book Club discusses a novel that includes these lines: “I’m aware, I really am fully aware that it’s impossible, in my case especially it’s impossible, to live a long and happy life when you drink. But how can you live a long and happy life if you don’t drink?”

Sarah Weinman shares a piece of an “impolite” 1961 interview with Shel Silverstein. The whole interview is worth a read. (Q: “You used to sell hot dogs when the Chicago Cubs were playing, and the White Sox. What did you learn about people from this experience?” A: “I learned they like mustard. . . .”) . . . I don’t know much (of any depth) about Jim Carroll, who died last week, but I was transfixed by this clip of him talking about his youthful basketball career and basketball generally. . . . A gift idea for the book-loving baseball fans in your life: author jerseys. I particularly like Bartleby and Poe (with the raven on front, not the heart). I might have to make it out to the launch party at Freebird Books in Brooklyn on Sunday to get my hands on one. Paper Cuts likes the shirts, too. . . . I learned about John Gall because the various book-design sites I visit would often write about his work. Now, Gall has his own blog, which I’ve added to the Links page. . . . Tonight in New York, the European Book Club discusses a novel that includes these lines: “I’m aware, I really am fully aware that it’s impossible, in my case especially it’s impossible, to live a long and happy life when you drink. But how can you live a long and happy life if you don’t drink?”

Monday, September 14th, 2009

Later this month, MIT will publish Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals

Later this month, MIT will publish Asylum: Inside the Closed World of State Mental Hospitals , a book by photographer Christopher Payne that documents (stunningly, as far as I can tell) the decaying institutions that were once devoted to caring for the mentally ill.

, a book by photographer Christopher Payne that documents (stunningly, as far as I can tell) the decaying institutions that were once devoted to caring for the mentally ill.

Oliver Sacks’ introductory essay has been published in a different form in the New York Review of Books. It’s only available online to subscribers, but Jenny Davidson transcribed a few paragraphs to share.

The Book Bench offers a slide show of six photos.

Monday, September 14th, 2009

Daniel Menaker — author, longtime editor at The New Yorker, longtime top gun at Random House, and of course, occasional Second Pass contributor — offers an excellent guide to the frustrations of the book publishing industry. He does some rough math to illustrate the trouble in getting noticed:

Daniel Menaker — author, longtime editor at The New Yorker, longtime top gun at Random House, and of course, occasional Second Pass contributor — offers an excellent guide to the frustrations of the book publishing industry. He does some rough math to illustrate the trouble in getting noticed:

[S]ome 150,000 books are published in the United States every year. Let’s [. . .] be really draconian and say that only 10 percent of those books would be in any way appealing to generalist readers of some intelligence. Let’s take 50 percent of that 10 percent, for no reason at all, just to be even meaner, and we end up with 7,500 books. That means that on average one hundred and fifty more or less worthwhile books are published every week in this country. Let’s cut that number in half, just to make the floor of our metaphorical abattoir really bloody. That makes seventy-five decent books a week. (By the way, that number is about twice the rough and generous estimate I’ve made based on actual experience.) How are seventy-five at-least-half-decent books going to receive serious and discriminating reviews in the few important places remaining for serious reviews every week? To say nothing of getting attention from prominent publicity outlets, like NPR and Charlie Rose and Jon Stewart? They’re not. They’re simply not. These statistical circumstances make publishing into a kind of grand cultural roulette, in which your chances of winning any significant pot are very, very small.

Meanwhile, Norman Geras confronts an even bigger number — the number of books in the world — and finds an odd comfort:

Suppose you read four books a week every week for 70 years. Allowing for a day here and there where you’re unable to read, we can call that 200 books a year, and 14,000 books over the whole three score years and ten. It’s a lot of books. But relative to all the books there are, it’s a tiny, tiny fraction. According to the guy who manages the Google Books metadata team, at the latest count the books in the world now total 168,178,719. Your 14,000 books are just 0.008324477724 per cent of that. You can think of it as follows. Suppose all the books in the world made up a single calendar year, and you were reading through the pages of that year, cover to cover. Then, 14,000 books - and that’s going some - would only get you through the first 44 minutes of the year. There’d still be 364 days, 23 hours and 16 minutes that you hadn’t read. And if you get through fewer than 14,000 books in your lifetime, it will look even worse. Comforting in a way.

Monday, September 14th, 2009

I read somewhere recently that copies of Dan Brown’s new novel, The Lost Symbol, which drops tomorrow like it’s hot, were being kept in some kind of giant cage, the door of which was secured by two different locks, and no one knew the combo to both locks. I’m not kidding.

I read somewhere recently that copies of Dan Brown’s new novel, The Lost Symbol, which drops tomorrow like it’s hot, were being kept in some kind of giant cage, the door of which was secured by two different locks, and no one knew the combo to both locks. I’m not kidding.

Well, Janet Maslin found a way into the cage! Or — less fun — maybe the Times just ignored the publisher’s embargo. Either way, Maslin’s review is in today’s paper. If you care, she says the book is “impossible to put down.” I’ll likely solve this problem by not picking it up in the first place.

. . . the author uses so many italics that even brilliant experts wind up sounding like teenage girls. And Mr. Brown would face an interesting creative challenge if the phrases “What the hell…?,” “Who the hell … ?” and “Why the hell … ?” were made unavailable to him. The surprises here are so fast and furious that those phrases get quite the workout.

Friday, September 11th, 2009

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

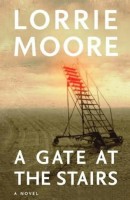

Lorrie Moore’s return from a decade-long absence with A Gate at the Stairs has rightfully set off a flurry of coverage. The Times gave it the paper’s patented double-barrel coverage, with a Michiko Kakutani review in the daily paper and Jonathan Lethem’s take in the Sunday Book Review. Kakutani liked it (“[Moore’s] most powerful novel yet”) and, um, so did Lethem (“It’s a novel that brandishes some ‘big’ material: racism, war, etc. — albeit in Moore’s resolutely insouciant key.”) Claire Dederer says the presence of so much plot is “quite a change for Moore” and the novel is a “brilliant feat.” Second Pass contributor John Davidson finds the first half of the novel a disappointment, “Yet miraculously — indeed, when it’s almost too late — Moore turns her story around.” . . . In The Nation, Kim Phillips-Fein rounds up a group of books about the conservative movement in America and offers a smart analysis of them. (“For conservatives, it seems that their most crushing defeats herald their greatest victories. Given these Houdini acts, it is surprising that until recently there has been no significant body of scholarship on the history of postwar conservatism.”) . . . In the New York Review of Books, Gary Wills considers one of those books on conservatism, The Death of Conservatism by Sam Tanenhaus. . . . Isabel Berwick believes that Nurtureshock is a book that “every parent should read”: “This book’s great value is to show that much of what we take to be the norms of parenting – ie, what’s good for children – is actually non-scientific and based on our own adult social anxieties.” . . . The TLS review J. M. Coetzee’s latest, part novel and part autobiography. (“Metafictional playfulness aside, the interviews collectively produce a poignant, cubistic portrait – by turns pointedly critical, affectionate and indifferent – of the fictional Coetzee.”)

Lorrie Moore’s return from a decade-long absence with A Gate at the Stairs has rightfully set off a flurry of coverage. The Times gave it the paper’s patented double-barrel coverage, with a Michiko Kakutani review in the daily paper and Jonathan Lethem’s take in the Sunday Book Review. Kakutani liked it (“[Moore’s] most powerful novel yet”) and, um, so did Lethem (“It’s a novel that brandishes some ‘big’ material: racism, war, etc. — albeit in Moore’s resolutely insouciant key.”) Claire Dederer says the presence of so much plot is “quite a change for Moore” and the novel is a “brilliant feat.” Second Pass contributor John Davidson finds the first half of the novel a disappointment, “Yet miraculously — indeed, when it’s almost too late — Moore turns her story around.” . . . In The Nation, Kim Phillips-Fein rounds up a group of books about the conservative movement in America and offers a smart analysis of them. (“For conservatives, it seems that their most crushing defeats herald their greatest victories. Given these Houdini acts, it is surprising that until recently there has been no significant body of scholarship on the history of postwar conservatism.”) . . . In the New York Review of Books, Gary Wills considers one of those books on conservatism, The Death of Conservatism by Sam Tanenhaus. . . . Isabel Berwick believes that Nurtureshock is a book that “every parent should read”: “This book’s great value is to show that much of what we take to be the norms of parenting – ie, what’s good for children – is actually non-scientific and based on our own adult social anxieties.” . . . The TLS review J. M. Coetzee’s latest, part novel and part autobiography. (“Metafictional playfulness aside, the interviews collectively produce a poignant, cubistic portrait – by turns pointedly critical, affectionate and indifferent – of the fictional Coetzee.”)

Thursday, September 10th, 2009

Every Thursday on the blog brings a post about a paperback book.

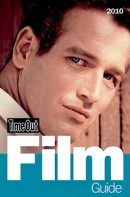

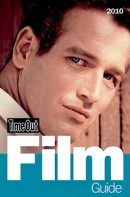

The annually updated Time Out Film Guide has always separated itself from the pack with sleek aesthetics, but the just-published 2010 edition

The annually updated Time Out Film Guide has always separated itself from the pack with sleek aesthetics, but the just-published 2010 edition reaches new heights by enhancing Paul Newman’s baby blues on the front cover and using the same striking color as a keynote throughout the interior.

reaches new heights by enhancing Paul Newman’s baby blues on the front cover and using the same striking color as a keynote throughout the interior.

There are dozens of movie guides to choose from every year, but the London-based Time Out’s is the most elegantly designed, user-friendly and comprehensive. It’s true that it doesn’t have a lot of what the DVD generation knows as “extras.” There are long lists of actors and directors in the back, a guide to 100 notable movie web sites up front, and not much else. But at more than 1,350 (small-type) pages already, it’s hard to complain about a lack of anything.

Most importantly, the book is full of sharp writing. When it says of Night of the Hunter that “(Charles) Laughton’s only stab at directing…turned out to be a genuine weirdie,” those last two words may sound vague, but if you’ve seen the movie you know they’re right on. As is this, at the end of the review for Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven: “Eventually…the narrative collapses, leaving its audience breathlessly suspended between a 90-minute proof that all the bustling activity in the world means nothing, and the perfection of Malick’s own perverse desire to catalogue it nonetheless. Compulsive.” Even when it errs and insults something as great as The Muppet Movie, it does it in a style all its own: “…the attitude towards Miss Piggy and Camilla the Chicken is, well, less than progressive.”

A small sampling of other potent opinions:

The Da Vinci Code: “The stars sprint through two and a half hours of chemistry-free exposition and condescending explanations of the past 2,000 years of ecclesiastical history.”

Bull Durham: “Sarandon is sexier reading Emily Dickinson’s poems fully clothed than most actresses would be writhing naked on a bed.”

Garden State: “That American ‘indie’ cinema isn’t what it once was is all too evident in this utterly innocuous concoction: two parts quirky-but-cute, one part pure mush.”

Like all such guides, the best way to experience this one is simply to rifle through it and allow sudden connections to keep you rifling. Doing just that this afternoon, I discovered there was such a thing as The Gong Show Movie, a “cringingly diabolical spin-off.”

Thursday, September 10th, 2009

Wallace Shawn has written several plays, and his acting credits number 125 on IMDb. But like the brilliant and versatile Alec Guinness, who will always remain the Jedi in the brown robe to some, to many Shawn will always be most famous for his (hysterical) turn as Vizzini in The Princess Bride.

Wallace Shawn has written several plays, and his acting credits number 125 on IMDb. But like the brilliant and versatile Alec Guinness, who will always remain the Jedi in the brown robe to some, to many Shawn will always be most famous for his (hysterical) turn as Vizzini in The Princess Bride.

Now, a collection of Shawn’s essays has been published, and the Huffington Post has posted an adapted version of the book’s introduction. It begins with some pleasurably playful metaphysics:

has been published, and the Huffington Post has posted an adapted version of the book’s introduction. It begins with some pleasurably playful metaphysics:

At any rate, I didn’t ask to be an individual, but I find I am one, and by definition I occupy a space that no other individual occupies — in other words, for what it’s worth, I have my own point of view. I’m not proud to be me, I’m not excited to be me, but I find that I am me, and like most other individuals, I send out little signals, I tell everyone else how everything looks from where I am.

Later, Shawn has some fun with the image of Eleanor Roosevelt to describe the differences between his skepticism and his mother’s earnest charity:

Mother loved UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund, which helped poor children all over the world, and she loved the United Nations; and, to her, being an American meant being a person who loved the United Nations and was a friend to poor children all over the world, like Eleanor Roosevelt and Adlai Stevenson. . . . I never became as nice as my mother. But by the time I was 45 I understood a few things that she’d overlooked. I suppose I’m something like what my mother would have been if she’d gone down into her basement and stumbled on Eleanor Roosevelt murdering babies there.

(Via Book Bench)

Wednesday, September 9th, 2009

Two new trailers for movies adapted from books: Walter Kirn’s Up in the Air, made by Jason Reitman (Juno and Thank You for Smoking), and David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, helmed by John Krasinski of The Office fame. The Up in the Air trailer is very artfully done, though the organizing conceit is pretty goofy. Brief Interviews would seem awfully tough to adapt, but we’ll see. . . . Jacket Copy interviews the proprietor of a blog called Slaughterhouse 90210, which matches photos from bad TV with favorite quotes from literature. . . . Shelfari begins a feature showcasing author’s bookshelves with Neil Gaiman’s enviable library. . . . Granta is previewing its forthcoming “Chicago” issue, which includes a great cover by Chris Ware, by sharing some advance praise. . . . Here’s a list of used bookstores all around the world. This will come in handy when I win the lottery and spend the rest of my days checking them off one by one. (Note to self: Start playing the lottery.) . . . Scott Pack alerts us that a London bookshop is asking for a list of your five favorite books. In return, you’re entered in a competition that could win you 20 free books. . . . In case you missed it on one of the other thousand blogs that posted it, the Booker shortlist has been announced.

Two new trailers for movies adapted from books: Walter Kirn’s Up in the Air, made by Jason Reitman (Juno and Thank You for Smoking), and David Foster Wallace’s Brief Interviews with Hideous Men, helmed by John Krasinski of The Office fame. The Up in the Air trailer is very artfully done, though the organizing conceit is pretty goofy. Brief Interviews would seem awfully tough to adapt, but we’ll see. . . . Jacket Copy interviews the proprietor of a blog called Slaughterhouse 90210, which matches photos from bad TV with favorite quotes from literature. . . . Shelfari begins a feature showcasing author’s bookshelves with Neil Gaiman’s enviable library. . . . Granta is previewing its forthcoming “Chicago” issue, which includes a great cover by Chris Ware, by sharing some advance praise. . . . Here’s a list of used bookstores all around the world. This will come in handy when I win the lottery and spend the rest of my days checking them off one by one. (Note to self: Start playing the lottery.) . . . Scott Pack alerts us that a London bookshop is asking for a list of your five favorite books. In return, you’re entered in a competition that could win you 20 free books. . . . In case you missed it on one of the other thousand blogs that posted it, the Booker shortlist has been announced.

Tuesday, September 8th, 2009

The Guardian interviews and profiles the great William Trevor:

The Guardian interviews and profiles the great William Trevor:

“If you take away the sadness from life itself,” he muses, “then you are taking away a big and a good thing, because to be sad is rather like to be guilty. They both have a very bad press, but in point of fact, guilt is not as terrible a position as it is made out to be. People should feel guilty sometimes. I’ve written a lot about guilt. I think that it can be something that really renews people.”

The rest includes thoughts on religion, his work schedule, his unhappy parents, and his own long, happy marriage.

(Via Norm Geras)

Tuesday, September 8th, 2009

When I started this site, I described myself as a “relative Luddite.” And that’s true, as far as someone can be a Luddite and run a web site. So when I read predictions of books on paper disappearing, I bristle (in addition to thinking such predictions are wrong). Of course, I’m not alone. “Pedro of hawthorn” has my back:

‘I welcome the day when I can ditch that heavy book and download a dozen titles on to my lightweight e-reader’. Good for you, just don’t peddle your jargonistic, dystopian brain-cell sapping vision of a concentrationless techno fueled post human post book world on the rest of us simple reflective paper loving folk.

Tuesday, September 8th, 2009

Jack Pendarvis debuts a new column at the Oxford American with a doozy, about reading Woody Allen and Roy Blount, Jr., and about insiders and outsiders in art, and about being southern, and about how Steve Allen was a “slick, affected, old square.” It starts:

There’s a false notion that Woody Allen has never achieved widespread popularity among bumpkins like myself. Allen has encouraged the perception: “Some of my films have never played south of the Mason-Dixon line,” he told Roger Ebert just a few years back.

That may be true, but I saw all of them from Annie Hall through Husbands and Wives on the big screen in Mobile, Alabama (a forty-minute trip from my home in Bayou La Batre), and Manhattan Murder Mystery through Scoop in Atlanta.

I’ll admit the pace slacked off once I moved to Mississippi.

“I don’t like him,” said Miss Deanne, one of the women who drove us to school in the carpool when I was in the eighth grade, “but I know he’s a genius.”

She was reacting to my hard-won paperback of Without Feathers, one of Allen’s humor collections. The first time I took it up to the counter, the clerk said it was “too grown-up” for me and refused to sell it. So, of course, I skulked around until another clerk showed up, and bought it from her.

Read the whole thing.

Monday, September 7th, 2009

A beautiful Labor Day here in New York, so I’m off to enjoy it. Regular posting will pick up again tomorrow, with a new review in Circulating and some action on the blog as well.

Friday, September 4th, 2009

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Bookforum has an early review of Jonathan Lethem’s latest, which goes on sale in mid-October. I’ll see for myself, but the reviewer, Hari Kunzru, is not a fan:

Bookforum has an early review of Jonathan Lethem’s latest, which goes on sale in mid-October. I’ll see for myself, but the reviewer, Hari Kunzru, is not a fan:

At times, Chronic City is almost a caricature of the type of writing James Wood skewered as “hysterical realism.” The irritating names, the hyperactive plotting, the relative lack of interest in psychology, and the general atmosphere of conspiracy and connectivity are all hallmarks of a genre that (pace Wood) vastly expanded the possibilities of the postwar novel but has now ossified into a repertoire of gestures, most of which Chronic City seems compelled to repeat.

Elsewhere, E. L. Doctorow’s latest, which imagines the life of famous New York shut-ins the Collyer brothers, also has critics considerably less than ecstatic. In the Times, Michiko Kakutani says that Doctorow has “produc[ed] a slight, unsatisfying, Poe-like story that turns out to be a study in morbid psychology.” . . . In the just-published September issue of Open Letters, Sam Sacks writes about Doctorow’s novel (“the book suffers from a want of invention. [It] feels simultaneously slight and verbose.”) along with two other New York novels, by Colum McCann and Colm Tóibín. . . . Edward Luttwak manages the rare deeply smart-and-breezy combination a review of two books, one a history of Central Eurasia and another about Attila the Hun. (“The extraordinary reputation of Attila and his Huns requires an explanation, because they had so much competition.”) He also unequivocally criticizes the inability of academics to confront important aspects of military history. . . . Christian House praises a “bibliomemoir” by British academic Rick Gekoski, who guides us on “a tour of 25 books that are particularly special to him, we learn the part each played in his romantic, professional and intellectual development.”

Thursday, September 3rd, 2009

Every Thursday on the blog brings a post about a paperback book.

The North Carolina-based Merge Records is an independent label that is thriving while larger conglomerates try (and mostly fail) to play catch-up with the 21st century. Merge began 20 years ago as a way for Mac McCaughan and Laura Ballance to release records by their band, the seminal Superchunk, and the bands of their friends in the Chapel Hill scene. In Our Noise: The Story of Merge Records

The North Carolina-based Merge Records is an independent label that is thriving while larger conglomerates try (and mostly fail) to play catch-up with the 21st century. Merge began 20 years ago as a way for Mac McCaughan and Laura Ballance to release records by their band, the seminal Superchunk, and the bands of their friends in the Chapel Hill scene. In Our Noise: The Story of Merge Records , they’ve teamed up with journalist John Cook to produce an addictive oral history of the enterprise. Reading the oversized paperback, generously stuffed with reminiscences and personal photos from artists, will be an intense nostalgia trip for anyone who came of musical age in the early 1990s.

, they’ve teamed up with journalist John Cook to produce an addictive oral history of the enterprise. Reading the oversized paperback, generously stuffed with reminiscences and personal photos from artists, will be an intense nostalgia trip for anyone who came of musical age in the early 1990s.

With bands like Arcade Fire and Spoon currently in its stable, Merge is probably doing better business than ever in 2009, but the majority of the book covers its first decade, when it moved from a bedroom hobby to one of the most respected, influential labels in the country. In the introduction to the first chapter, we’re told that the Chapel Hillers learned lessons from Corrosion of Conformity, a 1980s band based in neighboring Raleigh that “didn’t believe in waiting around for someone with money to tell them that it was okay for them to make records” and knew that “making noise wasn’t rocket science.”

Chapters covering Superchunk and the broader history of Merge alternate with chapters that serve as mini-histories of bands like The Magnetic Fields, Lambchop, Spoon and Neutral Milk Hotel. The latter is maybe most compelling, because after touring to support the Anne Frank-inspired cultic masterpiece, In the Aeroplane Over the Sea, the band’s leader, Jeff Mangum, essentially disappeared from the music world, even declining an invitation to open for R.E.M. He became — and remains — “the J. D. Salinger of indie rock.”

Mangum declined to be interviewed for the book (like any good Salinger would, though he did send along a brief note of praise for Merge), but the chapter on his band offers a shaggy portrait of their “Bad News Bear quality” that helps to dispel any mythic aura. As fellow Merger Matt Suggs said: “Most bands who tour have a method of loading the van where everything just kind of fits. And with them, it always looked like a three-year-old had packed the f***ing thing. They’d open the door and here would come a cymbal rolling out, and they’d go chasing it.”

The real charm of the collection is in its more candid moments, which read like a yearbook made by a committee of just the smart, cool kids. One photo caption reads, “Mac’s parents’ van after catching fire in New Mexico in 1989.” One interviewee admits, “This is going to sound really stupid, and I know I sound stupid saying it. But I was the king of the scene at the time.” McCaughan and Ballance openly discuss their 1994 romantic breakup, which didn’t (permanently, anyway) splinter the band. (A mutual friend: “Laura broke up with Mac because he was a jerk.” Mac: “I take umbrage at that description of me.”)

Recounted elsewhere are the difficulties of driving across a road covered in rabbits, the help of parents in naming bands, Sammy Hagar’s surprisingly durable wisdom about the creative process and Ballance’s account of how Merge came to be Merge:

The label was totally Mac’s idea. To call it “Merge” was my idea. We were driving through Colorado, and I started reading road signs while I was thinking about a name for it. I actually thought it was a pretty dumb name for a long time. But it’s certainly better than “Pronghorn Antelope,” which is another thing I saw while I was driving on that trip.

Wednesday, September 2nd, 2009

The Millions recently interviewed Phillip Lopate about his latest book, Notes on Sontag

The Millions recently interviewed Phillip Lopate about his latest book, Notes on Sontag , the first in Princeton’s Writers on Writers series. Lopate on Sontag’s grab for the brass ring:

, the first in Princeton’s Writers on Writers series. Lopate on Sontag’s grab for the brass ring:

Sontag felt the big game was fiction. And that’s where you win the Noble Prize. You don’t win it for writing essays. That’s understandable and that would’ve been great had she been a great fiction writer. Some people can do both, but she lacked a deep sympathy for other people — which is okay if you’re a critic because you don’t have to be that empathetic if you’re a critic, you just have to know what you think about something. And she lacked, for the most part, a sense of humor. It’s hard to be a great novelist without those two things. . . . I’m not saying anything that devastating because she was so good an essayist, it’s not a crime not to be a terrific fiction writer also. It’s just that because I love the essay, I regret that she came to put her eggs in another basket.

And on how that lack of humor inspired his mischievous side:

One of the amusing sides for me in the book is that Sontag was a brilliant writer who was not particularly known for having a sense of humor. A lot of my material is comic, more or less, and so I thought that even though Sontag isn’t funny I could find a way to write in an amusing way about her and about myself. Because, in a way, there’s nothing funnier than someone who takes herself very seriously and has a solemn reverence for greatness. So I was able to play with that.

I think that one of the main things that gets me going as a writer is the opportunity to do mischief. And in this particular respect I was analyzing one of the sacred cows of contemporary literature, an icon really. I knew that I was on thin ice a lot and that itself piqued my interest because I could get in a lot of trouble.

Wednesday, September 2nd, 2009

From The Master by Colm Tóibín:

by Colm Tóibín:

Minny died in March, a year since he had last seen her. He was still in England. He felt it as the end of his youth, knowing that death, at the last, was dreadful to her. She would have given anything to live. In the years that followed, he longed to know what she would have thought of his books and stories, and of the decisions he made about his life. This sense of missing her deep and demanding response made itself felt to Gray and Holmes as well, and also to William. All of them wondered in their nervous ambition and great, agitated egotism what Minny would have thought about them or said about them. Henry wondered, too, what life would have had for her and how her exquisite faculty of challenge could have dealt with a world which would inevitably attempt to confine her. His consolation was that at least he had known her as the world had not, and the pain of living without her was no more than a penalty he paid for the privilege of having been young with her. What once was life, he thought, is always life and he knew that her image would preside in his intellect as a sort of measure and standard of brightness and repose.

A bounty of lists from the Oxford American: The ten

A bounty of lists from the Oxford American: The ten

The other day, browsing at the local B&N, I came across an alarmingly thick novel written by Ralph Nader, and now

The other day, browsing at the local B&N, I came across an alarmingly thick novel written by Ralph Nader, and now

A few weeks ago, the New York Times

A few weeks ago, the New York Times  I’m a very big baseball fan, but I had no idea the Tampa Bay Rays had an outfielder who would

I’m a very big baseball fan, but I had no idea the Tampa Bay Rays had an outfielder who would  From

From  The new fall issue of The Paris Review features an interview with James Ellroy. In

The new fall issue of The Paris Review features an interview with James Ellroy. In  A lively, beautifully illustrated

A lively, beautifully illustrated  Over at The Millions, they’re counting down the top 20 novels since the turn of the millennium. The methodology and a general intro to the project

Over at The Millions, they’re counting down the top 20 novels since the turn of the millennium. The methodology and a general intro to the project  Caleb Crain

Caleb Crain  In his mid-30s, Dennis Covington was feeling depressed. A college English teacher who felt that his job was “minor and absurd,” he yearned for an adventure “in which the risks were real.” He found one. After reporting on the trial of an Alabama preacher who was accused of trying to kill his wife with poisonous snakes, Covington immersed himself in the Appalachian world of holy snake handlers. The resulting book,

In his mid-30s, Dennis Covington was feeling depressed. A college English teacher who felt that his job was “minor and absurd,” he yearned for an adventure “in which the risks were real.” He found one. After reporting on the trial of an Alabama preacher who was accused of trying to kill his wife with poisonous snakes, Covington immersed himself in the Appalachian world of holy snake handlers. The resulting book,  Sarah Weinman shares

Sarah Weinman shares  Later this month, MIT will publish

Later this month, MIT will publish  Daniel Menaker — author, longtime editor at The New Yorker, longtime top gun at Random House, and of course, occasional

Daniel Menaker — author, longtime editor at The New Yorker, longtime top gun at Random House, and of course, occasional  I read somewhere recently that copies of Dan Brown’s new novel, The Lost Symbol, which drops tomorrow like it’s hot, were being kept in some kind of giant cage, the door of which was secured by two different locks, and no one knew the combo to both locks. I’m not kidding.

I read somewhere recently that copies of Dan Brown’s new novel, The Lost Symbol, which drops tomorrow like it’s hot, were being kept in some kind of giant cage, the door of which was secured by two different locks, and no one knew the combo to both locks. I’m not kidding. Lorrie Moore’s return from a decade-long absence with A Gate at the Stairs has rightfully set off a flurry of coverage. The Times gave it the paper’s patented double-barrel coverage, with

Lorrie Moore’s return from a decade-long absence with A Gate at the Stairs has rightfully set off a flurry of coverage. The Times gave it the paper’s patented double-barrel coverage, with  The annually updated Time Out Film Guide has always separated itself from the pack with sleek aesthetics, but

The annually updated Time Out Film Guide has always separated itself from the pack with sleek aesthetics, but  Wallace Shawn has written several plays, and his acting credits

Wallace Shawn has written several plays, and his acting credits  Two new trailers for movies adapted from books: Walter Kirn’s

Two new trailers for movies adapted from books: Walter Kirn’s  The Guardian

The Guardian  Bookforum has

Bookforum has  The North Carolina-based Merge Records is an independent label that is thriving while larger conglomerates try (and mostly fail) to play catch-up with the 21st century. Merge began 20 years ago as a way for Mac McCaughan and Laura Ballance to release records by their band, the seminal Superchunk, and the bands of their friends in the Chapel Hill scene. In

The North Carolina-based Merge Records is an independent label that is thriving while larger conglomerates try (and mostly fail) to play catch-up with the 21st century. Merge began 20 years ago as a way for Mac McCaughan and Laura Ballance to release records by their band, the seminal Superchunk, and the bands of their friends in the Chapel Hill scene. In  The Millions

The Millions