Monday, June 29th, 2009

One of the new books I’m most looking forward to this fall is Lorrie Moore’s A Gate at the Stairs . It’s her first book of new material in 11 years, and her first novel since 1994’s excellent Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?

. It’s her first book of new material in 11 years, and her first novel since 1994’s excellent Who Will Run the Frog Hospital? Moore has a short story in this week’s New Yorker, which may be an excerpt from the novel. I’m guessing yes. Here’s how it starts:

Moore has a short story in this week’s New Yorker, which may be an excerpt from the novel. I’m guessing yes. Here’s how it starts:

The cold came late that fall, and the songbirds were caught off guard. By the time the snow and wind began in earnest, too many had been suckered into staying, and instead of flying south, instead of already having flown south, they were huddled in people’s yards, their feathers puffed for some modicum of warmth. I was looking for a babysitting job. I was a student and needed money, so I would walk from interview to interview in these attractive but wintry neighborhoods, past the eerie multitudes of robins pecking at the frozen ground, dun gray and stricken—though what bird in the best of circumstances does not look a little stricken—until at last, late in my search, at the end of a week, startlingly, the birds had disappeared. I did not want to think about what had happened to them. Or, rather, that is an expression—of politeness, a false promise of delicacy—for in fact I wondered about them all the time: imagining them dead, in stunning heaps in some killing cornfield outside of town, or dropped from the sky in twos and threes for miles down along the Illinois state line.

Thursday, June 25th, 2009

A continuing series that highlights books recently acquired by publishing houses for future release. Each post features a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

The Cherry:

Steve Wick’s Eyewitness to the Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, the story of legendary American journalist William L. Shirer, who witnessed firsthand and reported on the rise of Hitler and the Nazis in Europe and their ultimate demise.

The Pit:

Actress Jennifer Love Hewitt’s The Day I Shot Cupid, exploring the new landscape of modern dating and offering a wide range of practical tips, from text-flirting and IM-ing to what men and women really want, and how to start over after a breakup.

Tuesday, June 23rd, 2009

My thanks to eagle-eyed reader (and Scrabble enthusiast) M.B., who pointed out that my IAICIZED in the post three below about Word Freak should be LAICIZED. (It’s been fixed in the original post, too.) In his book, Fatsis had the L at the front lowercase, which threw me off. I’m telling you, Scrabble people are serious. And so you know, “laicize” is a verb meaning “to remove the clerical character or nature of; secularize.” Don’t say this site never taught you anything.

Tuesday, June 23rd, 2009

Over at Granta, Maud Newton and Alexander Chee exchange thoughts about the novels that Jean Rhys and Ford Madox Ford wrote after their affair. It makes for a compelling companion to Newton’s review of the Jean Rhys bio above. A taste:

Ford probably saw Rhys as a (tainted) embodiment of the love interest of The Good Soldier. And honestly, I believe he was hot for Rhys very specifically even before they met. He’d read a lightly fictionalized version of her journals, been struck by her acute renderings of loneliness and poverty, fantasized about her exotic Dominican background, and decided (assuming she was pretty, of course) that he, finally, would be the man to save her.

Even the most depressive writers spin out happily-ever-after tales when they’re plotting their own life stories, and Ford was no exception. That’s what I think.

Tuesday, June 23rd, 2009

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Jill Lepore has a typically brilliant piece in this week’s New Yorker. It begins and ends as a review of recently published parenting memoirs by Michael Lewis and Ayelet Waldman, but it’s really about the fact that “the notion that parenthood is a distinct stage of life, shared by men and women, is historically in its infancy.” . . . David Lynch isn’t my ball of wax, but if he’s yours, Brian Slattery recommends Midnight Picnic by Nick Antosca (“part ghost story, part revenge story, except that the experience of reading it is less like either narrative and more like having a waking nightmare.”). . . . Two brief takes on a brief new bio of George Eliot: Ian Pindar asks why we haven’t started calling Eliot by her real name, Marian Evans; and Rhoda Koenig wonders whether Eliot’s “emphasis on moral instruction” will keep her work from being widely appreciated in the future. . . . David Oshinsky reads a new biography of I. F. Stone and wishes for a more nuanced view. . . . Two new novels owe a debt to Mary McCarthy’s The Group. How do they measure up to their inspiration?

Jill Lepore has a typically brilliant piece in this week’s New Yorker. It begins and ends as a review of recently published parenting memoirs by Michael Lewis and Ayelet Waldman, but it’s really about the fact that “the notion that parenthood is a distinct stage of life, shared by men and women, is historically in its infancy.” . . . David Lynch isn’t my ball of wax, but if he’s yours, Brian Slattery recommends Midnight Picnic by Nick Antosca (“part ghost story, part revenge story, except that the experience of reading it is less like either narrative and more like having a waking nightmare.”). . . . Two brief takes on a brief new bio of George Eliot: Ian Pindar asks why we haven’t started calling Eliot by her real name, Marian Evans; and Rhoda Koenig wonders whether Eliot’s “emphasis on moral instruction” will keep her work from being widely appreciated in the future. . . . David Oshinsky reads a new biography of I. F. Stone and wishes for a more nuanced view. . . . Two new novels owe a debt to Mary McCarthy’s The Group. How do they measure up to their inspiration?

Monday, June 22nd, 2009

I finally read Stefan Fatsis’ Word Freak

I finally read Stefan Fatsis’ Word Freak , a mixture of memoir and reportage about the competitive Scrabble world. Most of America read it several years ago. I almost did, too, but I’m glad I waited, because my last two years of obsessive online play prepared me to get a lot more out of it.

, a mixture of memoir and reportage about the competitive Scrabble world. Most of America read it several years ago. I almost did, too, but I’m glad I waited, because my last two years of obsessive online play prepared me to get a lot more out of it.

Fatsis correctly notes that the two most common expressions of casual players are “That’s a word?” and “That can’t be a word!” And then he writes, “To play competitive Scrabble, one has to get over the conceit of refusing to acknowledge certain words as real and accept that the game requires learning words that may not have any outside utility.”

A lot of those words are on display in Word Freak. To list just a handful: KAB, PANTOFLE, OUGUIYA, OQUASSA and LAICIZED. (There’s something childishly pleasing about the number of words in all caps throughout.) Many of these words are passed along without definition, since knowing what they mean isn’t really the point, but I did learn, for example, that “EXODOS” means “a concluding dramatic scene.”

If you haven’t read it, you should. You don’t need more than a minor interest in the game to enjoy it, since it revolves around larger-than-life characters. One of those characters is Matt Graham, a stand-up comedian who pops dozens of pills a day to (he thinks) maintain his energy and mental edge. I won a Scrabble board from Graham several years back at a comedy event downtown, where he offered the game to anyone in the audience who could stump him with an anagram. I believe he asked for 10 letters or more. I know from the book that my stumping him was dumb luck, because the letter clusters that he’s capable of anagramming are insane. The letters I gave him were:

AAACEILNORTU

Can you figure it out? Answer after the jump:

AERONAUTICAL

Friday, June 19th, 2009

Scott Pack writes about a screening of the TV and film work of experimental writer B.S. Johnson (pictured at left). The night was hosted by Jonathan Coe, a terrific writer himself, and the author of Like A Fiery Elephant

Scott Pack writes about a screening of the TV and film work of experimental writer B.S. Johnson (pictured at left). The night was hosted by Jonathan Coe, a terrific writer himself, and the author of Like A Fiery Elephant , a compelling and formally inventive biography of Johnson. The night featured a show called “Fat Man On a Beach.” Pack embeds an an eight-minute segment, and the rest appears to be available online. . . . Despite being a big Coen brothers fan, I’ve never been a big Lebowski fan. (Rim shot.) But the film’s reputation seems to be doing just fine without my enthusiasm, and soon a university press (Indiana, to be precise) will publish a book of analysis to please the cult. . . . Two writers recently shopped around biographies of David Foster Wallace, which are apparently very different in nature. One of them has sold. I’m not sure I’m ready for a project like that, and I wonder if I’m alone. . . . Response to yesterday’s post about Harold Bloom keeps coming in. One reader points to his own interaction with Bloom.

, a compelling and formally inventive biography of Johnson. The night featured a show called “Fat Man On a Beach.” Pack embeds an an eight-minute segment, and the rest appears to be available online. . . . Despite being a big Coen brothers fan, I’ve never been a big Lebowski fan. (Rim shot.) But the film’s reputation seems to be doing just fine without my enthusiasm, and soon a university press (Indiana, to be precise) will publish a book of analysis to please the cult. . . . Two writers recently shopped around biographies of David Foster Wallace, which are apparently very different in nature. One of them has sold. I’m not sure I’m ready for a project like that, and I wonder if I’m alone. . . . Response to yesterday’s post about Harold Bloom keeps coming in. One reader points to his own interaction with Bloom.

Thursday, June 18th, 2009

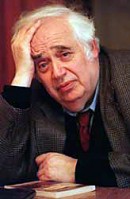

I never expected Harold Bloom to appear in The Onion outside of a headline like “Harold Bloom Exhumes Shakespeare, Eats Him” or “Harold Bloom’s Mother Barges Into Bathroom While He’s Reading Harry Potter” or “New Haven-Area Outback Steakhouse Offers Bloomin’ Onion With Real Bits of Harold Bloom.” That kind of thing. I did not expect the satirical paper to actually sit down with Bloom and discuss Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian

I never expected Harold Bloom to appear in The Onion outside of a headline like “Harold Bloom Exhumes Shakespeare, Eats Him” or “Harold Bloom’s Mother Barges Into Bathroom While He’s Reading Harry Potter” or “New Haven-Area Outback Steakhouse Offers Bloomin’ Onion With Real Bits of Harold Bloom.” That kind of thing. I did not expect the satirical paper to actually sit down with Bloom and discuss Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian .

.

But they did. Fear not — this being Bloom, there is a comedic element to the proceedings. Take this, for instance:

The Onion: You’ve been extremely critical of the politicization of teaching literature…

Bloom: Critical, young man, is hardly the word. I stand against it like Jeremiah prophesying in Jerusalem.

He claims it took him three tries to get through McCarthy’s bloody western, so perhaps the third time will be the charm for me, too. And he offers this spot-on summary of Don DeLillo’s Underworld : “a little long for what it does but nevertheless [it’s] the culmination of what Don can do.”

: “a little long for what it does but nevertheless [it’s] the culmination of what Don can do.”

(via Maud Newton)

Update: A reader writes in to let me know that Bloom was also interviewed not too long ago by Vice magazine, at greater length. An even weirder pairing…

Wednesday, June 17th, 2009

A continuing series that highlights books recently acquired by publishing houses for future release. Each post features a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

The Cherry:

Jill Lepore’s Backstories, excavating the forgotten history of contemporary problems and explaining the contested origins of American democracy, the chronic volatility of the economy, the wrenching separation of home and work, the antecedents of the war on terror, the checkered history of the idea of progress, and the centuries-long debate about the relationship between the past and the present.

The Pit:

Josie Brown’s The DILF, in which a stay-at-home mom befriends a former Master of the Universe turned stay-at-home dad, until the neighborhood’s mean mommies vying to make him the next notch on their bedposts turn on her.

Wednesday, June 17th, 2009

Here’s a marriage of good ideas:

Here’s a marriage of good ideas:

Last summer, Ed Park and Levi Stahl created The Invisible Library, an evolving list of books that have been mentioned in other works of art but don’t really exist.

Two of the better known “authors” represented are John Irving’s T.S. Garp and Kurt Vonnegut’s Kilgore Trout (with the wonderfully titled Pan-Galactic Three-Day Pass). Trout’s author “photo” by Vonnegut can be seen at left. The library also includes work from movies, like Family of Geniuses by Etheline Tenenbaum from Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums.

Now, a literary foundation and an “illustration collective” in the UK are bringing some of these titles to life for an art exhibit. Up through July 12 at the Tenderpixel Gallery in London, the Invisible Library becomes partially visible. Forty of the book’s covers have been designed for display, and artists of various stripes have written opening or closing pages for them. The rest will be an interactive experience, like so:

The collaboration continues throughout the exhibition as gallery attendees and workshop participants are invited to temporarily ’sign out’ these library books and carry on writing the developing narratives within. Thus by the close of the exhibition, the once blank pages of each book will be enlivened with imaginative poly-vocal stories.

Here are some photos from the scene. I hope someone in the U.S. — preferably New York, for convenience’s sake — brings the exhibit here.

Tuesday, June 16th, 2009

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

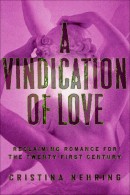

The Wall Street Journal takes a look at Cristina Nehring’s A Vindication of Love, in which Nehring focuses on certain relationships throughout history to mount a “rousing defense of imprudent ardor and romantic excess.” (“Any of these love stories submitted to a modern-day advice columnist would come back with a diagnosis of troubling pathologies: co-dependent adulterers, a sexually frustrated agoraphobe, a battered wife. Ms. Nehring wants us to see how impoverished this worldview is.”) . . . In the newest issue of n+1’s online book review, Jessica Weisberg makes a case for the work of the late Edgardo Vega Yunqué. Despite reservations about his strident political writing (“it’s like he’s covering himself in bumper-stickers”), Weisberg argues that his lack of concern about what other people thought was a strength: “The ideas that occasion his winks and asides are so personal that they do just the opposite of most self-conscious writing — they make his books more engaging.” . . . In the slim Sum

The Wall Street Journal takes a look at Cristina Nehring’s A Vindication of Love, in which Nehring focuses on certain relationships throughout history to mount a “rousing defense of imprudent ardor and romantic excess.” (“Any of these love stories submitted to a modern-day advice columnist would come back with a diagnosis of troubling pathologies: co-dependent adulterers, a sexually frustrated agoraphobe, a battered wife. Ms. Nehring wants us to see how impoverished this worldview is.”) . . . In the newest issue of n+1’s online book review, Jessica Weisberg makes a case for the work of the late Edgardo Vega Yunqué. Despite reservations about his strident political writing (“it’s like he’s covering himself in bumper-stickers”), Weisberg argues that his lack of concern about what other people thought was a strength: “The ideas that occasion his winks and asides are so personal that they do just the opposite of most self-conscious writing — they make his books more engaging.” . . . In the slim Sum , David Eagleman offers 40 brief vignettes, each describing a different possibility of the afterlife. Alexander McCall Smith calls it a “delightful, thought-provoking little collection belong[ing] to that category of strange, unclassifiable books that will haunt the reader long after the last page has been turned.” . . . Benjamin Schwarz reviews Golden Dreams, the eighth volume of Kevin Starr’s “monumental chronicle of California,” this volume covering the state’s “age of abundance” from 1950-1963. . . . Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley novels total nearly 1,500 pages. Michael Dirda tackles the whole lot.

, David Eagleman offers 40 brief vignettes, each describing a different possibility of the afterlife. Alexander McCall Smith calls it a “delightful, thought-provoking little collection belong[ing] to that category of strange, unclassifiable books that will haunt the reader long after the last page has been turned.” . . . Benjamin Schwarz reviews Golden Dreams, the eighth volume of Kevin Starr’s “monumental chronicle of California,” this volume covering the state’s “age of abundance” from 1950-1963. . . . Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley novels total nearly 1,500 pages. Michael Dirda tackles the whole lot.

Tuesday, June 16th, 2009

The Browser has been running a provocative series of interviews in which experts discuss the best books in their field.

The Browser has been running a provocative series of interviews in which experts discuss the best books in their field.

This week, Jessica Pressman, who teaches at Yale, analyzes and recommends some electronic literature. The truly electronic side of the conversation is about online texts. Pressman acknowledges that some of these works, like those at Young-hae Chang’s Heavy Industries, are more properly called “a textual performance,” since they incorporate music and graphics and — most crucially, to me — play continuously like a movie. (For a funny example, see “Cunnilingus in North Korea.” If you watch a few of the site’s other works, I think you’ll agree with me that this “revolution” in literature will mostly be a boon to the corrective-vision industry. Good lord.)

Pressman also discusses more conventional work (you know, on paper) that is formally influenced by technology, like the novels of Mark Danielewski. (About his House of Leaves : “It’s a horror story in some ways. My husband started reading it when I was out of town and he had to put it in a drawer and hide it because he got so frightened of it. He wouldn’t read it without my being there.”)

: “It’s a horror story in some ways. My husband started reading it when I was out of town and he had to put it in a drawer and hide it because he got so frightened of it. He wouldn’t read it without my being there.”)

My problem with this, if it’s a problem, is that approaching it as a radical development unique to the influence of technology on literature is misleading on two fronts. First, Pressman admits the influence can work the other way, that online works like Twelve Blue and The Jew’s Daughter owe a lot to the choose-your-own-adventure books that my generation grew up with. And she points out the “hypertextual” elements of works as old as Tristram Shandy and Pale Fire

and Pale Fire , meaning, to my mind, that Danielewski might have gotten around to his experiments with or without the dominance of Internet culture. Just as important to his work was the evolution of graphic design, printing techniques and their cost, etc.

, meaning, to my mind, that Danielewski might have gotten around to his experiments with or without the dominance of Internet culture. Just as important to his work was the evolution of graphic design, printing techniques and their cost, etc.

I guess I would call some of what’s online — certainly what’s at Young-hae Chang’s Heavy Industries — visual art rather than literature. Maybe that’s splitting hairs. But when Yale’s English department is the one investigating these things, maybe not. If Nabokov eventually gets thrown over for Flash animation, that will be a sad day.

Monday, June 15th, 2009

At the end of his essay about Cult Movies by Danny Peary (posted today on the Backlist; follow the stormtroopers), Andy Miller lists 61 movies to give Peary a start on a possible new volume. I’d heard of all the movie he lists but two, each with a doozy of a title — Can Hieronymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe And Find True Happiness? and Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains.

At the end of his essay about Cult Movies by Danny Peary (posted today on the Backlist; follow the stormtroopers), Andy Miller lists 61 movies to give Peary a start on a possible new volume. I’d heard of all the movie he lists but two, each with a doozy of a title — Can Hieronymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe And Find True Happiness? and Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains.

I did some research: Hieronymus Merkin (1969) was the bawdy brainchild (emphasis on child, it seems) of British singer and actor Anthony Newley. He plays a self-centered artist who reenacts his life — on a beach. With musical numbers. It features, among others, Milton Berle and Newley’s then-wife Joan Collins. Vincent Canby wrote that Newley “so over extends and overexposes himself that the movie comes to look like an act of professional suicide.” Another reviewer called the movie “a laughably bizarre bomb,” and wrote, “Newley leaves no psychedelic/art film cliché unturned, and circus sets, Sgt. Pepper costumes, obtrusive symbols, gratuitous nudity, and, of course, stock footage, all make their requisite appearances. He also treats his audience to multiple metafictional interruptions, which increase in frequency as the film progresses.” The original trailer can be seen here, and a clip here. I think I need to see this movie.

Fabulous Stains was an early ’80s production about an all-girl punk band, starring a teenage Diane Lane. Here’s the trailer, and this one’s going on my list, too.

Monday, June 15th, 2009

From Blockbuster by Tom Shone, a scene in which George Lucas screens Star Wars for several movie people in 1977:

by Tom Shone, a scene in which George Lucas screens Star Wars for several movie people in 1977:

[Alan] Ladd hated Harrison Ford’s performance — thought it was too camp — and resolved to ask Lucas to fix it in the editing, but for the moment he said nothing and simply left. Everyone else headed out to a Chinese restaurant; as soon as they sat down Lucas asked them, “All right, whaddya guys really think?” [Brian] De Palma plowed into it: “It’s gibberish,” he said. “The first act, where are we? Who are these fuzzy guys? Who are these guys dressed up like the Tin Man from Oz? What kind of movie are you making here? You’ve left the audience out. You’ve vaporized the audience.”

Thursday, June 11th, 2009

About six years ago, I got an e-mail from my friend Bill Wasik telling me (and others who got the note, all of us asked to forward it to as many people as we could, without betraying a connection to Bill) to show up at Claire’s Accessories, a small, somewhat shabby establishment at Broadway and Astor Place offering “an assortment of products geared toward teen girls.” The purpose of crowding into Claire’s was . . . nonexistent. I got there a few minutes early, at which time I saw several police milling around and a police wagon parked outside the store. Someone had squealed. As Bill has said, “[The police] made it look as if a terrorist had threatened to wage jihad against Claire’s Accessories.” (A funny idea, and I can see the talking heads now: “They hate us for our barrettes.”)

About six years ago, I got an e-mail from my friend Bill Wasik telling me (and others who got the note, all of us asked to forward it to as many people as we could, without betraying a connection to Bill) to show up at Claire’s Accessories, a small, somewhat shabby establishment at Broadway and Astor Place offering “an assortment of products geared toward teen girls.” The purpose of crowding into Claire’s was . . . nonexistent. I got there a few minutes early, at which time I saw several police milling around and a police wagon parked outside the store. Someone had squealed. As Bill has said, “[The police] made it look as if a terrorist had threatened to wage jihad against Claire’s Accessories.” (A funny idea, and I can see the talking heads now: “They hate us for our barrettes.”)

So the first “flash mob” was dispersed before it ever gathered, but Bill, nothing if not smart and resourceful, got around the problem. Flash mobs then thrived at various locations throughout that summer. And like the UK version of “The Office” or Barry Sanders, they retired while still on top. And now there’s this: Bill’s book, And Then There’s This: How Stories Live and Die in Viral Culture , which includes details about the flash mob project but also takes a much broader look at how Internet culture and viral sensations (see: Susan Boyle, the “Yes, We Can” video, et al.) are changing the way we think about and react to the world around us. Throughout the book, Bill also writes about other projects he’s undertaken to better understand what goes into culture-stirring circa 2009, including a web site that showed how the New York Times might look to a rabid conservative and an online campaign to protest a trendy indie-rock band.

, which includes details about the flash mob project but also takes a much broader look at how Internet culture and viral sensations (see: Susan Boyle, the “Yes, We Can” video, et al.) are changing the way we think about and react to the world around us. Throughout the book, Bill also writes about other projects he’s undertaken to better understand what goes into culture-stirring circa 2009, including a web site that showed how the New York Times might look to a rabid conservative and an online campaign to protest a trendy indie-rock band.

And Then There’s This is a smart, lively examination of the way that almost all of us are spending our time these days, for better or worse. If you’re in New York, Bill will be reading on June 23 at the Barnes & Noble in Tribeca. Additional tour dates can be found on his official site.

Wednesday, June 10th, 2009

It seems you can use Google and a barcode scanner to create a personal, searchable library of all your books. The details are here. I’m not sure how I feel about this (as if my uncertainty matters to the ceaselessly attacking future), but I do find it depressing that the guy in the brief instructional video is importing Google Apps books. Hey, let’s use computers to create databases of computer books and then search for computer information! 010001001!!

(Via Books, Inq.)

Tuesday, June 9th, 2009

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Allen Barra scratches his head over Chuck Palahniuk’s latest. (“Reading Pygmy is like trying to do a crossword puzzle while riding a horse underwater.”) . . . Mark Oppenheimer reviews George Scialabba’s What Are Intellectuals Good For?, “as succinct and companionable a tour through major American thinkers of the past century as you’re likely to get anywhere. . . . Scialabba makes me want to use my library card.” . . . In the new Believer, Steve Hely reviews 11 “imaginary” beach reads. . . . Nicole Lanctot says that Mark Rudd’s account of his time as a political radical “concludes that much of the Weathermen’s activities had the opposite effect of what was intended.”

Allen Barra scratches his head over Chuck Palahniuk’s latest. (“Reading Pygmy is like trying to do a crossword puzzle while riding a horse underwater.”) . . . Mark Oppenheimer reviews George Scialabba’s What Are Intellectuals Good For?, “as succinct and companionable a tour through major American thinkers of the past century as you’re likely to get anywhere. . . . Scialabba makes me want to use my library card.” . . . In the new Believer, Steve Hely reviews 11 “imaginary” beach reads. . . . Nicole Lanctot says that Mark Rudd’s account of his time as a political radical “concludes that much of the Weathermen’s activities had the opposite effect of what was intended.”

Monday, June 8th, 2009

Joseph Sullivan gives a well-deserved rave to the cover art for Philip Roth’s forthcoming The Humbling . . . . Not sure how a movie can dramatize bad writing, but it seems that the documentary Bad Writing will try. . . . Album covers reimagined as beat-up paperbacks. (Via.) . . . A couple of RIPs for the literary web, one more belated than another: Wyatt Mason is done blogging for Harper’s, and Readerville is closing shop after nine years. . . . Lastly, Scott Pack posts two great pictures of Audrey Hepburn. This is not book-related, but I don’t care, and I don’t imagine you do either.

. . . . Not sure how a movie can dramatize bad writing, but it seems that the documentary Bad Writing will try. . . . Album covers reimagined as beat-up paperbacks. (Via.) . . . A couple of RIPs for the literary web, one more belated than another: Wyatt Mason is done blogging for Harper’s, and Readerville is closing shop after nine years. . . . Lastly, Scott Pack posts two great pictures of Audrey Hepburn. This is not book-related, but I don’t care, and I don’t imagine you do either.

Monday, June 8th, 2009

Given that there’s a new movie based on her work being released just about every Friday and she’s been paired with zombies to hit the bestseller list, you’re probably not worried about the depth of affection out there for Jane Austen. But just in case, here’s Jane Austen Today, a blog that includes lists of favorite sequels to Austen novels, questions as to the whereabouts of actors who have appeared in Austen adaptations, and character “throwdowns,” in which readers are asked to vote on which actor or actress better played a particular character.

Speaking of Austen-inspired movies, I liked this, from a recent letter to the London Review of Books written by Kate Brayshay:

It is sad to think that there is a generation who, when they try to conjure Lizzy Bennet from the page, will have to fight back images of Keira Knightley pouting and pretending not to be beautiful in a mud-hemmed dress.

Thursday, June 4th, 2009

I’ve rarely seen a book get reviewed over such a long period of time as Brad Gooch’s recent biography of Flannery O’Connor. (I’d put Carlene Bauer’s review of it for this site up against anybody.) Now comes a look from The New Republic, including this, which made me smile:

Perhaps she shared the skepticism of Zola, whose novel Lourdes she was given on the trip, and who famously quipped that he saw a lot of abandoned crutches on the road from Lourdes but no artificial legs. Or perhaps she disliked the vulgarity of miracles on demand. In any case, it was not physical health that O’Connor was after, at Lourdes or anywhere else. “I prayed there for the novel I was working on, not for my bones, which I care about less,” she wrote.

And this, about O’Connor’s religion:

Like others before him, Gooch overestimates O’Connor’s theological sophistication. . . . The truth is that O’Connor liked the Catholic Church because she didn’t have to think about it. Just as she once claimed that she wanted to remain twelve forever, with none of the complications of puberty, she thought the Church was most trustworthy around the thirteenth century.

Thursday, June 4th, 2009

A continuing series that highlights books recently acquired by publishing houses for future release. Each post features a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

The Cherry:

Nigel Jones’ Tower: An Epic History of the Tower of London, Castle, Royal palace, prison, torture chamber and place of execution — no building has been more intimately involved in Britain’s story than this mighty, brooding stronghold in the very heart of London, a place which has stood at the epicentre of dramatic, bloody and frequently cruel events for almost a thousand years.

The Pit:

Sue Ownes Wright’s Sirius About Murder, in which a wealthy and powerful patron for Alpine Paws Park is found strangled with a dog groomer’s leash near a pet psychic booth at a Howloween benefit for Tahoe’s tailwaggers, and a woman and her dog find themselves dewlap deep in a murder investigation.

Wednesday, June 3rd, 2009

The opening sentence of A Prayer for Owen Meany by John Irving:

by John Irving:

I am doomed to remember a boy with a wrecked voice — not because of his voice, or because he was the smallest person I ever knew, or even because he was the instrument of my mother’s death, but because he is the reason I believe in God; I am a Christian because of Owen Meany.

Wednesday, June 3rd, 2009

“J.D. Salinger hasn’t published much fiction in the last half-century, but the guy can still crank out a lawsuit when he needs to.” This from the Wall Street Journal’s law blog, which analyzes the merits of the author’s suit against a forthcoming “sequel” to The Catcher in the Rye .

.

Wednesday, June 3rd, 2009

I spent a few hours last week at Book Expo America in New York, but I won’t bore you with the details. (Any details would be boring, I’m afraid; picture a medical supplies convention, but with books.) While there, though, I discovered that there are an awful lot of promising titles coming this fall, which should mean good things for this site. One thing I missed but would have liked to catch in person was a conversation with John Irving and Richard Russo, moderated by Chip McGrath. Irving (Last Night in Twisted River

I spent a few hours last week at Book Expo America in New York, but I won’t bore you with the details. (Any details would be boring, I’m afraid; picture a medical supplies convention, but with books.) While there, though, I discovered that there are an awful lot of promising titles coming this fall, which should mean good things for this site. One thing I missed but would have liked to catch in person was a conversation with John Irving and Richard Russo, moderated by Chip McGrath. Irving (Last Night in Twisted River ) and Russo (That Old Cape Magic

) and Russo (That Old Cape Magic ) both have new novels due out before long. Irving talked about his process, and I thought this was interesting:

) both have new novels due out before long. Irving talked about his process, and I thought this was interesting:

Melville also said something that struck me when I was a young writer. He said, ‘Woe to him who seeks to please rather than appall.’ To appall is good. My fellow New Englander Stephen King would agree. . . . I think before I begin a novel, something about the story has to terrify me. Something about it has to be in that category of accident or tragedy that I never want to happen to myself or to anyone I love. And until I’m frightened about something, until I can’t stop thinking about something I would rather not think about, I don’t feel I have a story that I want to spend the next four or five years writing. . . . There’s a degree of repetition in most novelists I think of as serious, because we don’t so much get to choose our subjects as our obsessions choose us. There you are in what feels like the early phase of a totally new book before you realize, ‘Oh, there’s another dead child. There’s another missing parent. Oh, it’s that story again.’ And it’s not conscious. It’s obsessive.

Tuesday, June 2nd, 2009

If you were trying to think of Marilynne Robinson’s influences, I’d bet it would take a while to get to Edgar Allan Poe. But here is Robinson (found via Maud Newton) discussing the impact Poe had on her as a young reader:

Poe at his best is not imaginable without the excesses for which he must be forgiven. I think I have always loved him because to love him requires loyalty. Those gothic dreams of his are the sort of thing a pre-adolescent girl might be enthralled by, and I did notice that brilliance and learning were among the glories of his perishing damsels. But I had to defend him and myself together from the idea that the tales were simply lurid or morbid. I knew better because I could not stop memorizing his poems. To say them and hear them taught me to feel the deeper coherences of language, as if words ordered by their sounds and suggestions were a charm that opened more meaning than words contain. And I learned from him that an ancient or an alien language had the intimate sound of a whisper at my ear.

Monday, June 1st, 2009

Having only sisters (three of them) myself, I’m still interested in Brothers: 26 Stories of Love and Rivalry

Having only sisters (three of them) myself, I’m still interested in Brothers: 26 Stories of Love and Rivalry , partly because I figure the sibling experience has plenty of resonance across genders, and partly because the lineup in the book is formidable. It includes Richard Ford, Ethan Canin, Mikal Gilmore, Tobias Wolff and Second Pass contributor (among many other, more illustrious things) Daniel Menaker.

, partly because I figure the sibling experience has plenty of resonance across genders, and partly because the lineup in the book is formidable. It includes Richard Ford, Ethan Canin, Mikal Gilmore, Tobias Wolff and Second Pass contributor (among many other, more illustrious things) Daniel Menaker.

The collection also includes a piece by David Kaczynski, who, like Gilmore , has a notorious brother. He writes: “I’ll start with the premise that a brother shows you who you are — and also who you are not. He’s an image of the self, at one remove . . . You are a ‘we’ with your brother before you are a ‘we’ with any other.”

, has a notorious brother. He writes: “I’ll start with the premise that a brother shows you who you are — and also who you are not. He’s an image of the self, at one remove . . . You are a ‘we’ with your brother before you are a ‘we’ with any other.”

Monday, June 1st, 2009

The New Yorker just published its Summer Fiction issue, some of which is available online. It includes stories by Jonathan Franzen, Aleksandar Hemon, Yiyun Li and others.

The issue also features an essay by Louis Menand about a very old question (can creative writing be taught?), taken up with Menand’s usual style and intelligence. It begins:

Creative-writing programs are designed on the theory that students who have never published a poem can teach other students who have never published a poem how to write a publishable poem.

. It’s her first book of new material in 11 years, and her first novel since 1994’s excellent Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?

Moore has a short story in this week’s New Yorker, which may be an excerpt from the novel. I’m guessing yes. Here’s how it starts:

Jill Lepore has

Jill Lepore has  I finally read Stefan Fatsis’

I finally read Stefan Fatsis’  Scott Pack writes about

Scott Pack writes about  I never expected Harold Bloom to appear in The Onion outside of a headline like “Harold Bloom Exhumes Shakespeare, Eats Him” or “Harold Bloom’s Mother Barges Into Bathroom While He’s Reading Harry Potter” or “New Haven-Area Outback Steakhouse Offers Bloomin’ Onion With Real Bits of Harold Bloom.” That kind of thing. I did not expect the satirical paper to actually sit down with Bloom and discuss Cormac McCarthy’s

I never expected Harold Bloom to appear in The Onion outside of a headline like “Harold Bloom Exhumes Shakespeare, Eats Him” or “Harold Bloom’s Mother Barges Into Bathroom While He’s Reading Harry Potter” or “New Haven-Area Outback Steakhouse Offers Bloomin’ Onion With Real Bits of Harold Bloom.” That kind of thing. I did not expect the satirical paper to actually sit down with Bloom and discuss Cormac McCarthy’s  Here’s a marriage of good ideas:

Here’s a marriage of good ideas: The Wall Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal  The Browser has been running

The Browser has been running  At the end of his essay about Cult Movies by Danny Peary (posted today on the Backlist; follow the stormtroopers), Andy Miller lists 61 movies to give Peary a start on a possible new volume. I’d heard of all the movie he lists but two, each with a doozy of a title — Can Hieronymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe And Find True Happiness? and Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains.

At the end of his essay about Cult Movies by Danny Peary (posted today on the Backlist; follow the stormtroopers), Andy Miller lists 61 movies to give Peary a start on a possible new volume. I’d heard of all the movie he lists but two, each with a doozy of a title — Can Hieronymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humppe And Find True Happiness? and Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains. About six years ago, I got an e-mail from my friend Bill Wasik telling me (and others who got the note, all of us asked to forward it to as many people as we could, without betraying a connection to Bill) to show up at Claire’s Accessories, a small, somewhat shabby establishment at Broadway and Astor Place offering “an assortment of products geared toward teen girls.” The purpose of crowding into Claire’s was . . . nonexistent. I got there a few minutes early, at which time I saw several police milling around and a police wagon parked outside the store. Someone had squealed. As Bill

About six years ago, I got an e-mail from my friend Bill Wasik telling me (and others who got the note, all of us asked to forward it to as many people as we could, without betraying a connection to Bill) to show up at Claire’s Accessories, a small, somewhat shabby establishment at Broadway and Astor Place offering “an assortment of products geared toward teen girls.” The purpose of crowding into Claire’s was . . . nonexistent. I got there a few minutes early, at which time I saw several police milling around and a police wagon parked outside the store. Someone had squealed. As Bill  Allen Barra

Allen Barra  I spent a few hours last week at Book Expo America in New York, but I won’t bore you with the details. (Any details would be boring, I’m afraid; picture a medical supplies convention, but with books.) While there, though, I discovered that there are an awful lot of promising titles coming this fall, which should mean good things for this site. One thing I missed but would have liked to catch in person was a conversation with John Irving and Richard Russo, moderated by Chip McGrath. Irving (

I spent a few hours last week at Book Expo America in New York, but I won’t bore you with the details. (Any details would be boring, I’m afraid; picture a medical supplies convention, but with books.) While there, though, I discovered that there are an awful lot of promising titles coming this fall, which should mean good things for this site. One thing I missed but would have liked to catch in person was a conversation with John Irving and Richard Russo, moderated by Chip McGrath. Irving ( Having only sisters (three of them) myself, I’m still interested in

Having only sisters (three of them) myself, I’m still interested in