Archives, April, 2009

Wednesday, April 29th, 2009

From Clive James’ introduction to Flying Visits , a collection of his travel writing:

, a collection of his travel writing:

Even within the confines of Europe, the idea that all airports were the same turned out to be exactly wrong. In fact any airport anywhere immediately reflects the political system, economic status and cultural characteristics of the country where it is situated. During the supposedly swinging Sixties, both of the major London airports gave you a dauntingly accurate picture of Britain’s true condition, with one delay leading to another, a permanent total breakdown of the information service supposedly responsible for telling you all about it, and food you would not have given to a dog. Zurich airport, on the other hand, was like a bank which had merged with a hospital in order to manufacture chocolates.

Tuesday, April 28th, 2009

(Ed. Note: From now on, In the Ether will link to anything but reviews of books in other publications. Reviews will have their own round-up post, as yet untitled.)

Speaking of Geoff Dyer, an interview with him. “I’m really not interested in entertaining the troops and can’t imagine anything worse than being a so-called comic novelist. I never read comic novels: I almost never find them funny because they’re always holding up this tacit sign saying ‘LAUGH NOW’ so one sits there, grim-faced.” . . . How an unrequited high school crush put Cristina Henriquez on the path to becoming a writer. . . . Jessa Crispin of Bookslut fame is packing up and moving away from Chicago. She writes: “I think that maybe I treat cities like relationships, and one day I just wake up and realize it’s over.” To find out her landing place, click here. . . . The Caustic Cover Critic assesses a new line of redesigned classics. I’m partial to the look for In Cold Blood.

Tuesday, April 28th, 2009

Here’s a good idea: collecting one-star reviews of classic works on Amazon. Entertaining, certainly, but soon after falling down the one-star rabbit hole, you may be persuaded that nothing is worth your time. To wit, here’s a succinct review of The Great Gatsby :

:

terrible, terrible, terrible! This incredibly boring book, although considered an american classic, is dismal. Don’t bother with it, and read Douglas Adams instead.

Ah, but here’s a review of Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy :

:

it sucked it was boring and stupid anyone who thinks ball point pens are funny is an idiot

So, fair warning: These critics clearly have such high standards that you may never read another book.

(Via The Millions)

Tuesday, April 28th, 2009

In her recent review of Geoff Dyer’s new novel (above), Sarah Douglas makes reference to Thomas Mann, whose Death in Venice

In her recent review of Geoff Dyer’s new novel (above), Sarah Douglas makes reference to Thomas Mann, whose Death in Venice is clearly echoed in Dyer’s work.

is clearly echoed in Dyer’s work.

Thomas’ brother Heinrich (at left, standing, with Thomas) is the focal point of Evelyn Juers’ House of Exile, which seems to have been published only in Australia so far. The book follows Heinrich and his second wife, Nelly Kroeger-Mann, as they flee 1930s Germany for France and eventually Los Angeles. Other historic characters in the cast include Virginia Woolf, Bertolt Brecht, and Joseph Roth. The TLS recently published an approving review:

It’s a very personal book: idiosyncratic, a little wandering, and finally scintillating and rather magical and a triumph. . . .

A third of the way into her book, with Hitler in power, and exile the order of the day, Juers evolves a different method. She has largely assembled her personnel by now; she confines herself to giving updates, going from one to another in strictly chronological order, each chapter is a calendar year, and this is where her book . . . really comes into its own, so that I would wish it many thousands of readers. . . . It is amazing how those years, and those people, and those dramas all live in her pages.

And of course, there’s Heinrich’s more famous brother:

There is, first and foremost, Thomas Mann, a creature of such superb habit and indurated routine as to have made himself – as though belonging to another species – almost impervious to distraction: a few magniloquent sentences in the morning, soup (teeth trouble) and a cigar at lunchtime (“smoked Personality cigars”); in the afternoon, correspondence and a walk with one of a relay of the dogs of those years (in another Windsor touch, one was driven to him, cross-country, by Sybille Bedford; in addition, “Thomas was always a keen recorder of the dogs he met”); in the evening, gramophone music or reading aloud or a trip to the theatre and then taking down whatever book it was time for (“Thomas read Rimbaud”) . . .

An Australian blogger also offers an enthusiastic recommendation:

Juers’ writing sings, her quiet asides about research never detracting from the drive forward, but enriching the conversational tone of this remarkable piece of literary life-work. It’s a work of great love as well as of scholarship, I think.

Tuesday, April 28th, 2009

And Here’s the Kicker is a book that features conversations with many successful humor writers about their craft. It’s coming out in July, but there are excerpts available now on the book’s official site. My favorite is this, from George Meyer, one of the geniuses behind The Simpsons:

You can see that sensibility in many episodes of The Simpsons. As opposed to most shows, The Simpsons is never afraid to mock religion and the religious.

I think what we’re really satirizing is moral certainty—the myopia of the pious. The religious ferociously defend their own beliefs, but if a Sioux wants to keep a Target store off his sacred land they’ll laugh in his face.

And this from Dave Barry, which can be applied to more than humor writing:

When you write humor, it’s not funny to you. It’s not even really that funny when you first think of the idea. There may be a glimmer of humor because it still seems vaguely original, but after a couple of days it’s not funny at all. You’re just trusting that it was, at some point, funny, and that your honing and tweaking is really improving it.

(Another interview with Meyer can be found here.)

Monday, April 27th, 2009

I’ll be traveling most of today, so the blog will get rolling again on Tuesday. For now, please enjoy Emily Votruba’s excellent piece on Simone Weil, which just went up on the Backlist.

Thursday, April 23rd, 2009

Thomas Pynchon’s new novel is due out in August, and the cover is, um, different for him.

Thursday, April 23rd, 2009

In his review of Thom Gunn’s Selected Poems (above), Richard Wirick praises the introduction written by August Kleinzahler. The Guardian recently ran a profile of the poet, which includes a take on his sometimes gruff exterior:

Others have wondered whether Kleinzahler, whose father worked in real estate and sent his son to the elite Horace Mann school in New York, assumes a bad-boy mask shaped for the authentically pock-marked features of Charles Bukowski or Gregory Corso. To [Adam] Kirsch, the “roughneck persona” appears to be “the product of a persistent American neurosis about poetry and art being unmasculine. To compensate for their presumed loss of masculine status, certain writers make alcohol and fighting part of their literary persona.”

I’m not very familiar with Kleinzahler’s work, but the profile is worth reading. (The shot of him with his cat is pretty great, too.) I liked his thoughts about why he hasn’t settled into any long-term academic job:

“I really feel that it’s an unsavoury business, sitting in a room and critiquing the poetry of youngsters who aren’t yet formed as adults, far less as writers, and who are highly professionalised and ambitious and want to be assured that they’re doing something of importance. It’s terrible to lie to young people. And that’s what it’s about.”

(Via Bookslut)

Wednesday, April 22nd, 2009

The Second Pass gets a mention in this lengthy, smart look at the future of books coverage. . . . A book is returned to a library, and a fine of more than $52,000 is waived. . . . “I am for progress to a degree but as yet have not become used to automobiles. I still prefer horses, say nothing about travelling in space ships.” A funny look at a crazy book. . . . A fascinating profile of novelist Hilary Mantel. . . . Mantel herself reviews a four-volume history of women. . . . Louis Begley reviews Franz Kafka: The Office Writings.

Wednesday, April 22nd, 2009

A continuing series that highlights books recently acquired for future publication. Each post features a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

The Cherry:

Peter Heather’s Empire and Barbarians: Migration, Development, and the Birth of Europe, a narrative of the first millennium AD that tells the story of the joining of Southern and Western Europe.

The Pit:

Gabi Steven’s The Time of Transition, in which the safeguards between the magical and human worlds weaken while new guardians are put in place; a magical bent on revenge plans to use the newest fairy godmother, a “Rare One,” possessor of mighty magic born of two humans, who does not yet know how to use her power, as his means of ruling both worlds.

Tuesday, April 21st, 2009

The opening sentence of The Girls of Slender Means by Muriel Spark:

by Muriel Spark:

Long ago in 1945 all the nice people in England were poor, allowing for exceptions.

Tuesday, April 21st, 2009

Jill Lepore is always worth reading. This week, she turns her attention to Edgar Allan Poe:

You love Poe or you don’t, but, either way, Poe doesn’t love you. A writer more condescending to more adoring readers would be hard to find. “The nose of a mob is its imagination,” he wrote. “By this, at any time, it can be quietly led.”

Tuesday, April 21st, 2009

Last week, the 50th anniversary of The Elements of Style

Last week, the 50th anniversary of The Elements of Style was noted far and wide. So was the book’s loudest critic, Geoffrey K. Pullum, who made his feelings known in the Chronicle of Higher Education. His opinion of the book is illustrated with many examples, but the gist is found early on: “Its advice ranges from limp platitudes to inconsistent nonsense.”

was noted far and wide. So was the book’s loudest critic, Geoffrey K. Pullum, who made his feelings known in the Chronicle of Higher Education. His opinion of the book is illustrated with many examples, but the gist is found early on: “Its advice ranges from limp platitudes to inconsistent nonsense.”

Levi Stahl points out that E. B. White himself had doubts about his authority on the subject. Stahl also includes a few eloquent thoughts of his own, including this one, with which I agree completely, and not only because I was a terrible grammar student:

. . . we learn to write well not by learning the rules of grammar or sussing out the parts of speech, but by reading and hearing and absorbing good writing, noting its cadences, its balance, its methods of telegraphing tone and emphasis. Of course we can’t learn to write well from Elements; we couldn’t even if its presentation of grammar were unimpeachable. A book of grammar, like a dictionary, is something we consult when we have a question. It is the mountain of other, non-instructional books we spend a lifetime reading that actually teaches us how to write.

Stahl then moves on to quote several of White’s wonderful letters .

.

Monday, April 20th, 2009

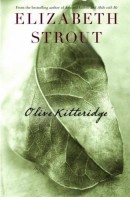

The 2009 Pulitzer Prize winners were just announced. I’ve listed the book categories below. (A full list of winners, including music, drama, and journalism can be found here.) I’ll have more thoughts on the winners (and finalists) later, but wanted to get this up.

The 2009 Pulitzer Prize winners were just announced. I’ve listed the book categories below. (A full list of winners, including music, drama, and journalism can be found here.) I’ll have more thoughts on the winners (and finalists) later, but wanted to get this up.

If you’re planning to buy any of this year’s winners, buying them through the links provided below will help support The Second Pass. Thanks.

Fiction

Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout

by Elizabeth Strout

History

The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family by Annette Gordon-Reed

by Annette Gordon-Reed

Biography or Autobiography

American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House by Jon Meacham

by Jon Meacham

Poetry

The Shadow of Sirius by W.S. Merwin

by W.S. Merwin

General Nonfiction

Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II by Douglas A. Blackmon

by Douglas A. Blackmon

Monday, April 20th, 2009

Reader Penny recommends Charles Chadwick’s It’s All Right Now on The Shelf today, and I second that — heartily. In fact, I plan on writing about the novel at greater length sometime in the future. (I played a very small, supporting role in its U.S. publication.)

Reader Penny recommends Charles Chadwick’s It’s All Right Now on The Shelf today, and I second that — heartily. In fact, I plan on writing about the novel at greater length sometime in the future. (I played a very small, supporting role in its U.S. publication.)

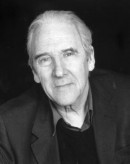

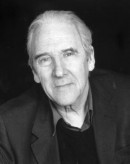

Chadwick (at left) was in his 70s when It’s All Right Now was published — he had been working on the book, on and off, for three decades. The New York Times recently looked at the trend of writers producing well into old age:

The geriatric writer, the one who persists into the twilight years, is something new. There were always exceptions, of course — long-lived authors who defied the actuarial tables. Thomas Hardy, for example, wrote (poetry, not novels) well into his 80s and once modestly confided that he remained sexually active as an octogenarian. (He was too old-fashioned to think there might be a connection.) But by and large writing used to be a profession whose practitioners, the great ones especially, died relatively young.

Friday, April 17th, 2009

A delightful essay by William Gass about his library at home (20,000 volumes and counting). He begins by detailing his time reading as a child, and in the Navy (”whatever readable books were aboard . . . a handful of Hemingway and a pinch of Faulkner”), and in graduate school at Cornell.

I used to have something bordering on an obsession for keeping books in good shape. I still do in special cases, but mostly I feel as Gass does here:

Collectors who do not care for books but only for their rarity prefer them in an unopened, pure and virginal condition, but such volumes have had no life, and now even that one chance has been taken from them, so that, imprisoned by stifling plastic, priced to flatter the vanity of the parvenu who has made its purchase, such a book sits out of the light in a glass-enclosed humidor like wine too old to open, too expensive to enjoy.

Whereas Mister Tatters, who has his economic failure marked on his flyleaf as a character in Dickens might by virtue of the quality, wear and soilage of his hat, cane and coat, has been enriched by a history: sold new in 1932 for $3.95, as used from the Gotham Book Mart in 1947 for 2 bucks, and marked down successively in pencil and then in crayon from 75 to 50, from 35 cents to a quarter during the decades since—owned by two who signed their names, one who added an address in Joliet—until it completed its journey to St. Louis, where it is picked from a barrow or a box at a garage sale or out of a bin in a Goodwill the way I found my copy of George Santayana’s The Sense of Beauty in 1982. It survived its adventures as admirably as Odysseus. I am rather free with my books and will let anyone who wants to kiss The Sense of Beauty’s cover in hopes of a bit of good luck in life.

(Via The Search Was the Thing)

Thursday, April 16th, 2009

The Pulitzer Prizes will be announced on Monday. In preparation, some are compiling the odds. Strikes me as a fairly weak list this year, with lots of lifetime-achievement types up for minor work, and I think they’re underrating Richard Price’s chances for Lush Life.

On a related note, and one in sync with the aim of this site, AbeBooks put together a list of the top 10 “forgotten” Pulitzer-winning novels.

(Via The Millions)

Thursday, April 16th, 2009

Terry Teachout addresses the issue of book dedications. (Someone just dedicated a work to him.)

One of my favorite dedications is in Kurt Vonnegut’s Welcome to the Monkey House:

For Knox Burger. Ten days older than I am. He has been a very good father to me.

Wednesday, April 15th, 2009

A consideration of William Maxwell’s The Château. . . . A friend of this site recommends a charming, recently republished children’s book. . . . An interview with an author who has done 16 book signings in D.C. airports over the last year and a half. (”I get fewer multiple sales. More people ignore me. More people don’t speak English.” He also discusses the upside.) . . . The Reading Experience isn’t overly thrilled with Andrew (A to Z), but still wonders why a bigger publisher wasn’t interested.

Wednesday, April 15th, 2009

Today on The Shelf, a reader recommends Disappearances by William Wiser. In 1982, Anatole Broyard had this to say about the novel in the New York Times:

[Wiser's] portrait of Paris and the Parisians is one of the best by an American since Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. There is a scene in a horse butcher’s that might serve as a textbook illustration of Henry James’s remark that “Landscape is character.”

Unfortunately for Wiser, Broyard wasn’t reviewing Disappearances at the time:

I’ve gone into this much detail about Mr. Wiser’s previous two books because I’m embarrassed by the poverty of Ballads, Blues and Swansongs, his latest one.

Wednesday, April 15th, 2009

From “A Home in the Neon,” an essay about living in Las Vegas by Dave Hickey, in his collection Air Guitar :

:

Most of all, I suspect that my unhappy colleagues are appalled by the fact that Vegas presents them with a flat-line social hierarchy . . . Membership in the University Club will not get you comped at Caesars, unless you play baccarat. Thus, in the absence of vertical options, one is pretty much thrown back onto one’s own cultural resources, and, for me, this has not been the worst place to be thrown. At least I have begun to wonder if the privilege of living in a community with a culture does not outweigh the absence of a “cultural community” and, to a certain extent, explain its absence. (Actually, it’s not so bad. My [Times Literary Supplement] and [London Review of Books] come in the mail every week, regular as clockwork, and just the other day, I took down my grandfather’s Cicero and read for nearly an hour without anyone breaking down my door and forcing me to listen to Wayne Newton.)

Tuesday, April 14th, 2009

Emily Bobrow reviews Peter Singer’s new book (above), which focuses on individuals’ ethical responsibilities in fighting global poverty. It’s an issue that most people would agree is important, but Singer’s specific approach is built to stir debate. In other areas, like his views about animal rights and abortion and the rights of disabled humans, he has generated quite a bit of controversy, even outrage. I went rummaging to find a few clips of Singer through the years:

Here, he’s interviewed about his new book by Tyler Cowen on Bloggingheads, a site which could be renamed TV For People Who Shouldn’t Be On TV. (Cowen looks like he’s being held captive in a military lab somewhere. Singer looks like, well, Peter Singer at too-close range.) Still, parts of the conversation are compelling. Here’s Singer talking to a BBC reporter not too many years ago, and here he is being interviewed a thousand years ago, when mustaches were in the middle of their shameful steroids era. (I would recommend only a quick look at the mustache in the last clip, because it is fierce. The talk about Hegel is less so.)

Tuesday, April 14th, 2009

If you’ve just found The Second Pass in the past few days, I hope you’re enjoying it, and please note: I would love to hear from you.

Let me know what you’re reading and enjoying (could be brand new, could have been published in 1826), and I may post your thoughts on The Shelf. These recommendations tend to run between 75 and 125 words.

And if you’d like to hear from me (occasionally) about happenings on the site, please sign up for the newsletter in the space provided to the right. (Helpfully located under the bar labeled “Newsletter.”) They’ll likely go out every other week or so, starting soon.

I can be reached at john@thesecondpass.com.

Tuesday, April 14th, 2009

Last weekend in one of my favorite bookstores, I came across Little People in the City: The Street Art of Slinkachu . Based in London, Slinkachu places very small hand-painted figures in urban environments. The results are a winning combination of whimsical and poignant.

. Based in London, Slinkachu places very small hand-painted figures in urban environments. The results are a winning combination of whimsical and poignant.

Several examples can be found at the artist’s blog.

Monday, April 13th, 2009

John Madera has an addictive blog devoted to people’s favorite novellas. The site starts with an introductory post by Madera, followed by posts from the 60 writers and editors Madera asked for recommendations. Renee Gladman comes up with a decent definition of a novella (a thorny, perhaps metaphysical and unsolvable issue), and Jim Hanas wonders about the effect technology will have on fiction’s form.

The composite list helpfully catalogs the novellas in alphabetical order. The most cited are obvious classics like Heart of Darkness (14 mentions), The Metamorphosis

(14 mentions), The Metamorphosis (12), Bartleby, the Scrivener

(12), Bartleby, the Scrivener (10), and The Dead

(10), and The Dead (9). But up there with them (10 mentions) is Ever

(9). But up there with them (10 mentions) is Ever by Blake Butler, which was new to me.

by Blake Butler, which was new to me.

Turns out Butler’s book is new to everyone, having come out in January. The comments made by those recommending it (“Whatever the hell Butler is talking about, he sure does talk about it pretty.” “The form is far from linear.” “This book contains something new.”) could be warnings just as easily as raves. And this excerpt is a bit David Markson-y for my taste. But hey, if it’s up your alley, you’re welcome.

Monday, April 13th, 2009

I’ll have more about this when it’s published in the U.S. this summer, but for now, the UK is reacting to Nick Laird’s new novel, Glover’s Mistake. . . . “When the Flock Changed,” an excerpt from Maud Newton’s novel-in-progress. . . . A review of Joe Queenan’s new memoir, Closing Time , which details his rough upbringing in Philadelphia. . . . Nelson George also had a tough childhood (in Brooklyn), and his new memoir, City Kid

, which details his rough upbringing in Philadelphia. . . . Nelson George also had a tough childhood (in Brooklyn), and his new memoir, City Kid , is “obsessed with work.” . . . A look back at the dawn of the Thatcher era and the literature that accompanied it.

, is “obsessed with work.” . . . A look back at the dawn of the Thatcher era and the literature that accompanied it.

Monday, April 13th, 2009

A continuing series that highlights books recently acquired for future publication. Each post features a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

The Cherry:

Christine Sismondo’s America Walks Into a Bar, a biography of America’s drinking establishments and how they influenced the country’s history, from the tavern in the Salem Witch Trials to speakeasies during Prohibition and beyond.

The Pit:

Hugo and Nebula award-winning author Greg Bear’s Halo trilogy, set in the time of the Forerunners, the creators and builders of the Halos, based on the hit video games.

Monday, April 13th, 2009

A piece on NPR about author photos — which doesn’t add much to the conversation and, fair warning, crashed my browser the first time I tried to play it — did get me thinking about the art. Marion Ettlinger is perhaps the only photographer truly famous for capturing authors, and her work inspires revulsion as often as respect. She has a distinct style, to be sure, and I like many of her portraits (like this one of Raymond Carver, for which she also has a soft spot).

But Ettlinger can be oddly dependent on props, like this shot of Jonathan Franzen, who looks like he’s just one element in a design exhibit at MoMA. Other times, she makes serious writers look like they’re sending out head shots to community theaters, as in this pic of John Irving.

Of course, these are subtle sins compared to the distinctly Ettlingerian categories that I like to call Too Much and Way Too Much.

Which isn’t to say that you need Ettlinger behind the lens to make strange self-presentation decisions. Just ask Tim Dorsey.

Friday, April 10th, 2009

The opening sentence of Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen by Larry McMurtry:

by Larry McMurtry:

In the summer of 1980, in the Archer City Dairy Queen, while nursing a lime Dr Pepper (a delicacy strictly local, unheard of even in the next Dairy Queen down the road — Olney’s, eighteen miles south — but easily obtainable by anyone willing to buy a lime and a Dr Pepper), I opened a book called Illuminations and read Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Storyteller,” nominally a study of or reflection on the stories of Nikolay Leskov, but really (I came to feel, after several rereadings), an examination, and a profound one, of the growing obsolescence of what might be called practical memory and the consequent diminution of the power of oral narrative in our twentieth-century lives.

and read Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Storyteller,” nominally a study of or reflection on the stories of Nikolay Leskov, but really (I came to feel, after several rereadings), an examination, and a profound one, of the growing obsolescence of what might be called practical memory and the consequent diminution of the power of oral narrative in our twentieth-century lives.

Thursday, April 9th, 2009

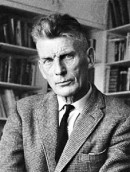

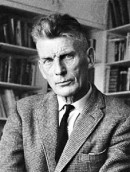

There have been many unqualified raves about the recently published volume of Samuel Beckett’s letters

There have been many unqualified raves about the recently published volume of Samuel Beckett’s letters (the first of four) — some of these raves bordering on mash notes — and they’ve left me curious. The book sounds compelling and worthwhile, but could a 782-page collection of letters by someone so famously difficult be pure pleasure? Leave it to Anthony Lane to provide the most satisfying consideration. He wonders how to recommend such a “dense agglomeration of ire and indecision,” eventually concluding that “what renders this collection, for all its tics and indulgences, far more of a spur than a letdown is the slowly welling sense of a writer mustering his powers.”

(the first of four) — some of these raves bordering on mash notes — and they’ve left me curious. The book sounds compelling and worthwhile, but could a 782-page collection of letters by someone so famously difficult be pure pleasure? Leave it to Anthony Lane to provide the most satisfying consideration. He wonders how to recommend such a “dense agglomeration of ire and indecision,” eventually concluding that “what renders this collection, for all its tics and indulgences, far more of a spur than a letdown is the slowly welling sense of a writer mustering his powers.”

Somewhere in between is this:

What we have here is not historically uncommon: the early progress of an intensely clever, emotionally febrile figure, whose worries are further chafed by his dismay at seeing how directionless that progress feels. When Beckett turns to Schopenhauer (again, a traditional path), in 1930, it is for the philosopher’s “intellectual justification of unhappiness—the greatest that has ever been attempted.” There is more than a tinge of Goethe’s Young Werther, who would have been lost without his sorrows; except that his were triggered by frustrated love, whereas the Beckett who stalks through these letters seems almost indecently loveless. True, there are fleeting mentions of his cousin Peggy Sinclair, to whom he had been close in the late nineteen-twenties. In “Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett,” James Knowlson claims that she had “initiated, then led, their sexual explorations,” and that Beckett’s urge to explore further, with other women, is confirmed by “the less discreet parts” of his correspondence, but, if so, these have been filed away by the finer discretion of the editors. “I had a nice friendly postcard from Peggy from the North Sea” is about as stormy as we get. She died, of tuberculosis, less than three years later, earning a frighteningly austere tribute from Beckett to McGreevy: “It appears that she and her fiancé had lately been indulging in regular paroxysms of plans of what they would do when they were married. She has been cremated.” The fiancé is said to be “inconsolable,” although whether Beckett himself required consoling, or whether he was striving to present himself as someone with no such needs, is impossible to gauge.

Wednesday, April 8th, 2009

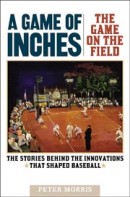

As baseball season gets started, it’s a good time for fans to luxuriate in Peter Morris’ encyclopedia A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball, published in two volumes, The Game on the Field

As baseball season gets started, it’s a good time for fans to luxuriate in Peter Morris’ encyclopedia A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball, published in two volumes, The Game on the Field and The Game Behind the Scenes

and The Game Behind the Scenes .

.

The tables of contents for the two books look more like a legal document, with areas of the game divided and subdivided, and take up a combined 27 pages.

On the Field starts with “The Things We Take For Granted” — nine innings, balls and strikes, overhand pitching, running counterclockwise — and moves on to parse baserunning, uniforms, umpires, fielding and equipment, among other categories. If you’re concerned about thoroughness, Morris has you covered. The sub-chapter on kinds of pitches runs 64 pages, from the fastball (“baseball’s first pitch”) to the Kimono Ball (a pitch thrown behind the back, an invention of Yankees left-hander Tommy Byrne that was immediately outlawed after he used it in a preseason game).

The second volume deals with off-field subjects like scouting, ballparks, statistics and marketing, and it houses the more tangential — often bizarre — material. In a chapter called “Variants,” we learn about baseball on ice. Morris writes, “With baseball and ice-skating both enjoying popularity in the early 1860s, it was inevitable that someone would try to combine them.” Yes, inevitable. In 1861, the Brooklyn Eagle ran this priceless account of one game played on the slippery surface:

It will be readily understood that the game when played upon ice with skates is altogether a different sort of affair from that which the Clubs are familiar with. The most scientific player upon the play ground finds himself out of his reckoning when he has got the runaway skates to depend on, and the best skater is the best player.

Less than five years later (it took that long?), the very same paper had seen enough:

We hope we shall have no more ball games on ice. . . . if any of the ball clubs want to make fools of themselves, let them go down to Coney Island and play a game on stilts.

Wednesday, April 8th, 2009

Wells Tower, whose debut collection of short stories was reviewed here by Daniel Menaker, is interviewed by The Book Bench (the books blog at The New Yorker). His response to a question about his revision process:

There’s this metaphor I settled on for revisions. I was in Alaska on a kayaking trip, and I was warned by this park ranger to be really careful in the arctic lakes when the moose are around. A male moose will jump into the lake with the idea that a female moose is on the other side, and then he’ll get to the other side and think that the female is on the other side, and often the moose will continue to go back and forth until he drowns from his own indecision. To me, it’s a sitting metaphor for revision. You can’t keep mindlessly pacing from one impulse to another or you’ll drive yourself insane.

Wednesday, April 8th, 2009

John Lanchester, always worth reading, considers Google Street View, and Google’s other ventures, all “poised on the margin between utopian and dystopian.” . . . I’ve had Vladimir Sorokin’s The Queue recommended to me on a couple of occasions, and it sits somewhere in my teetering to-read pile. Elaine Blair takes a look. . . . Alexander McCall Smith on the relationship between readers and fictional characters. . . . The bond between writers and poker. (On a related note of good news, James McManus has a history of poker coming out in the fall.)

recommended to me on a couple of occasions, and it sits somewhere in my teetering to-read pile. Elaine Blair takes a look. . . . Alexander McCall Smith on the relationship between readers and fictional characters. . . . The bond between writers and poker. (On a related note of good news, James McManus has a history of poker coming out in the fall.)

Tuesday, April 7th, 2009

Ken Kalfus, in a review of All Shall Be Well; And All Shall Be Well; And All Manner of Things Shall Be Well by Tod Wodicka:

Although Wodicka turns up a provocative thought here and there, this musing, typical of Burt’s grief-laden vaporousness, serves also to illustrate the artless, wordy and underarticulated writing that makes All Shall Be Well such a Black Death of a chore to read.

Tuesday, April 7th, 2009

A continuing series that highlights books recently acquired for future publication. Each post features a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

The Cherry:

Brett Martin’s Difficult Men, a look at the rise of cable television dramas since the late 1990’s, examining the cultural, technological and artistic forces that turned the 13-episode format into the ideal vehicle to tell the 21st Century American story, with The Sopranos‘ David Chase, The Wire’s David Simon, and Mad Men’s Matthew Weiner, among others, as main characters.

The Pit:

Relationship expert and CEO of seminar company PAX Programs Alison Armstrong’s Transforming a Frog Farmer, an engaging guide for women written in the style of fable that explores how understanding men’s inherent motivations and language is the secret to enchanting relationships.

Monday, April 6th, 2009

From So Long, See You Tomorrow

From So Long, See You Tomorrow by William Maxwell:

by William Maxwell:

Roaming the courthouse square on a Saturday night, the tenant farmers and their families were unmistakable. You could see that they were not at ease in town and that they clung together for support. The women’s clothes were not meant to be becoming but to wear well, to last them out. The back of the men’s necks was a mahogany color, and deeply wrinkled. Their hands were large and looked swollen or misshapen and sometimes they were short a finger or two. The discontented hang of their shoulders is possibly something I imagined because I would not have liked not owning the land I farmed. Very likely they didn’t either, but farming was in their blood and they wouldn’t have cared to be selling real estate or adding up columns of figures in a bank.

On the seventh day they rested; that is to say, they put on their good clothes and hitched up the horse again and drove to some country church, where, sitting in straight-backed cushionless pews, they stared passively at the preacher, who paced up and down in front of them, thinking up new ways to convince them that they were steeped in sin.

Monday, April 6th, 2009

In his review of Stephen King’s Danse Macabre (above), Jason Zinoman also considers the work of H. P. Lovecraft, which inspired King. This might not be the best exercise if, like me, you get down about your productivity, but consider the fact that Lovecraft only lived to 46 and then take a look at the list of his works. And scroll. And scroll. And scroll.

Granted, most of the list is made up of individual short stories and poems, but still: It’s gray and dreary here this morning, and I’m having some trouble summoning the energy to add warm milk to oatmeal.

Friday, April 3rd, 2009

I’m just learning of an April Fool’s joke pulled by the publisher Grove/Atlantic. It revolved around a fake novel called The Tornado Ashes Club, which the company had allegedly bought for an advance of mid-seven figures. News of the buy came complete with a promotional web site for the book. The plot summary was the first red flag:

I’m just learning of an April Fool’s joke pulled by the publisher Grove/Atlantic. It revolved around a fake novel called The Tornado Ashes Club, which the company had allegedly bought for an advance of mid-seven figures. News of the buy came complete with a promotional web site for the book. The plot summary was the first red flag:

A gunshot rings out on a Las Vegas night, and Silas Quilter’s life is shattered. Falsely accused, forced to flee from the law and from relentless bounty hunters, his only hope lies with an unlikely source of succor: his grandmother Evangeline. Together, they take to the American road in a Ford Maverick named Penelope. As they drive, Evangeline carries a special cargo: the ashes of a man she lost long ago. She tells Silas the story of their love, of his struggles that took him from the mud-drenched football fields of Pennsylvania to the hedgerows of war-torn Normandy, the marketplaces of Tunisia, and the vineyards of Peru. She tells Silas of his dying wish to have his ashes cast into a tornado.

A second, even redder flag could be found in an interview with the author:

What’s next for you?

Oh, I hate to talk about projects I’m working on. It de-powers them, you know? Strips away some of the magic.

You’ve got to give us something!

Okay, okay. I’ll tell you the title. The Wisdom of Acorns.

(Though maybe that flag isn’t red enough, given some of what’s published.)

In any case, what’s really being promoted by Grove/Atlantic is How I Became a Famous Novelist

In any case, what’s really being promoted by Grove/Atlantic is How I Became a Famous Novelist by Steve Hely, a forthcoming novel with a (slightly less earnest) tornado on its own cover. Hely’s tale tells the story of how a “‘pile of garbage’ called The Tornado Ashes Club became the most talked about, blogged about, read, admired, and reviled novel in America.”

by Steve Hely, a forthcoming novel with a (slightly less earnest) tornado on its own cover. Hely’s tale tells the story of how a “‘pile of garbage’ called The Tornado Ashes Club became the most talked about, blogged about, read, admired, and reviled novel in America.”

(Via Mark Athitakis and GalleyCat)

Thursday, April 2nd, 2009

This U.S.-shaped bookshelf (minus Hawaii and Alaska) is stunning, if not particularly, um, book-friendly (Texas looks like someone’s untended attic). It’s appropriate that I found it through Omnivoracious, the Amazon blog that recently went through the country, matching each state’s number of Electoral College votes with the same number of appropriate books.

Thursday, April 2nd, 2009

This essay by William Hazlitt, called “On Reading Old Books,” includes some thoughts that are appropriate for this site. Like this one:

This essay by William Hazlitt, called “On Reading Old Books,” includes some thoughts that are appropriate for this site. Like this one:

I do not think altogether the worse of a book for having survived the author a generation or two. I have more confidence in the dead than the living.

Oxford University Press recently published William Hazlitt: The First Modern Man by Duncan Wu. The Washington Post called it “a distinctly eye-opening biography.”

by Duncan Wu. The Washington Post called it “a distinctly eye-opening biography.”

(Via I’ve Been Reading Lately)

, a collection of his travel writing:

In her recent review of Geoff Dyer’s new novel (above), Sarah Douglas makes reference to Thomas Mann, whose

In her recent review of Geoff Dyer’s new novel (above), Sarah Douglas makes reference to Thomas Mann, whose  Last week, the 50th anniversary of

Last week, the 50th anniversary of  The 2009 Pulitzer Prize winners were just announced. I’ve listed the book categories below. (A full list of winners, including music, drama, and journalism

The 2009 Pulitzer Prize winners were just announced. I’ve listed the book categories below. (A full list of winners, including music, drama, and journalism  Reader Penny recommends Charles Chadwick’s It’s All Right Now on The Shelf today, and I second that — heartily. In fact, I plan on writing about the novel at greater length sometime in the future. (I played a very small, supporting role in its U.S. publication.)

Reader Penny recommends Charles Chadwick’s It’s All Right Now on The Shelf today, and I second that — heartily. In fact, I plan on writing about the novel at greater length sometime in the future. (I played a very small, supporting role in its U.S. publication.) There have been many unqualified raves about

There have been many unqualified raves about  As baseball season gets started, it’s a good time for fans to luxuriate in Peter Morris’ encyclopedia A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball, published in two volumes,

As baseball season gets started, it’s a good time for fans to luxuriate in Peter Morris’ encyclopedia A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball, published in two volumes,  From

From  I’m just learning of an April Fool’s joke pulled by the publisher Grove/Atlantic. It revolved around a fake novel called The Tornado Ashes Club, which the company had allegedly bought for an advance of mid-seven figures. News of the buy came complete with

I’m just learning of an April Fool’s joke pulled by the publisher Grove/Atlantic. It revolved around a fake novel called The Tornado Ashes Club, which the company had allegedly bought for an advance of mid-seven figures. News of the buy came complete with  In any case, what’s really being promoted by Grove/Atlantic is

In any case, what’s really being promoted by Grove/Atlantic is