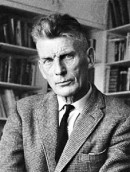

There have been many unqualified raves about the recently published volume of Samuel Beckett’s letters

There have been many unqualified raves about the recently published volume of Samuel Beckett’s letters (the first of four) — some of these raves bordering on mash notes — and they’ve left me curious. The book sounds compelling and worthwhile, but could a 782-page collection of letters by someone so famously difficult be pure pleasure? Leave it to Anthony Lane to provide the most satisfying consideration. He wonders how to recommend such a “dense agglomeration of ire and indecision,” eventually concluding that “what renders this collection, for all its tics and indulgences, far more of a spur than a letdown is the slowly welling sense of a writer mustering his powers.”

Somewhere in between is this:

What we have here is not historically uncommon: the early progress of an intensely clever, emotionally febrile figure, whose worries are further chafed by his dismay at seeing how directionless that progress feels. When Beckett turns to Schopenhauer (again, a traditional path), in 1930, it is for the philosopher’s “intellectual justification of unhappiness—the greatest that has ever been attempted.” There is more than a tinge of Goethe’s Young Werther, who would have been lost without his sorrows; except that his were triggered by frustrated love, whereas the Beckett who stalks through these letters seems almost indecently loveless. True, there are fleeting mentions of his cousin Peggy Sinclair, to whom he had been close in the late nineteen-twenties. In “Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett,” James Knowlson claims that she had “initiated, then led, their sexual explorations,” and that Beckett’s urge to explore further, with other women, is confirmed by “the less discreet parts” of his correspondence, but, if so, these have been filed away by the finer discretion of the editors. “I had a nice friendly postcard from Peggy from the North Sea” is about as stormy as we get. She died, of tuberculosis, less than three years later, earning a frighteningly austere tribute from Beckett to McGreevy: “It appears that she and her fiancé had lately been indulging in regular paroxysms of plans of what they would do when they were married. She has been cremated.” The fiancé is said to be “inconsolable,” although whether Beckett himself required consoling, or whether he was striving to present himself as someone with no such needs, is impossible to gauge.