Tuesday, December 14th, 2010

At the New Yorker’s Book Bench, Deborah Treisman interviews George Saunders, whose story “Escape from Spiderhead” appears in the magazine this week. Treisman starts with a question about the darkness of some of Saunders’ dystopian themes. His response, in part:

At the New Yorker’s Book Bench, Deborah Treisman interviews George Saunders, whose story “Escape from Spiderhead” appears in the magazine this week. Treisman starts with a question about the darkness of some of Saunders’ dystopian themes. His response, in part:

I’ve done a lot of (mostly defensive) thinking about this darkness thing, and have formulated a good amount of shtick along the way. So thanks for asking! One of the most truthful answers I’ve come up with is just to paraphrase Flannery O’Connor, who said that a writer can choose what he writes about, but can’t choose what he makes live. Somehow—maybe due to simple paucity of means—I tend to foster drama via bleakness. If I want the reader to feel sympathy for a character, I cleave the character in half, on his birthday. And then it starts raining. And he’s made of sugar.

Are people made of sugar? Is it raining? How often does a guy get cut in half on his birthday? Still, the story about the sugar-guy being cut in half on his birthday in the rain is not saying: this happens. It is saying, If this happened, what would that be like? Its subject becomes, say, undeserved misery—which does happen. We know that, we feel it. And maybe (the argument goes) it was necessary to make this exaggerated sugar-guy and cut him in half in order to remind ourselves, at sufficient volume, that undeserved misery exists—to sort of rarify and present that feeling so we might feel it anew.

Anyway, that’s the theory.

I pointed to another worthwhile interview with Saunders a while back.

Tuesday, December 14th, 2010

This guest post was written by Kevin Kinsella, a writer and translator living in Brooklyn. His translation of Sasha Chernyi’s Poems from Children’s Island, from Russian, is forthcoming from Lightful Press.

This guest post was written by Kevin Kinsella, a writer and translator living in Brooklyn. His translation of Sasha Chernyi’s Poems from Children’s Island, from Russian, is forthcoming from Lightful Press.

For Natasha Wimmer, the best thing a translator can do is “disappear” behind a text, a strategy that earned her a National Book Critics Circle Award in 2009 for her translation of Robert Bolaño’s novel 2666. But the San Francisco-based Center for the Art of Translation is doing everything it can to put the translator front and center.

For the past 17 years, the center has published Two Lines: World Writing in Translation, one of just a handful of publications devoted exclusively to the translation of international literature into English, a sort of translators’ night out where each translator very nearly gets to step out from behind the curtain of the text. Some Kind of Beautiful Signal , this year’s edition — edited by Wimmer and acclaimed poet Jeffrey Yang — continues this worthy tradition by delivering works by poets and fiction writers working in more than a dozen languages. The translated pieces are accompanied by excerpts of prose and entire poems in the original language on facing pages.

, this year’s edition — edited by Wimmer and acclaimed poet Jeffrey Yang — continues this worthy tradition by delivering works by poets and fiction writers working in more than a dozen languages. The translated pieces are accompanied by excerpts of prose and entire poems in the original language on facing pages.

According to Wimmer, each of the items included in the anthology, which takes its title from the translation of a line from Andrey Dmitriev’s story “Turn of the River,” relays a signal. “When we read in translation, those signals may come from far away, but they are strong and insistent,” Wimmer says. “Writers and translators — and readers — should remind themselves once again of the power of fiction in translation.”

And it would seem that no signal has further distance to travel to reach English readers than the anthology’s special selection of poetry from China’s Uyghur ethnic minority, edited by Yang, which gives readers the rare opportunity to experience the perspective of contemporary voices from a diverse culture that is thousands of years old — a culture increasingly under political pressures from the Chinese government.

Ironically, Wimmer’s own offering is a rendering into English of Bolaño’s “Translation is a Testing Ground,” an essay on the limits of translation. Probably written in the last year of his life, Bolaño’s piece is not especially kind to translation, but it does describe how great literature is able to survive even when poorly translated. In the essay, Bolaño describes how the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges saw a poorly translated production of Macbeth. Not only was the translation terrible, but so were the actors — even the seats were uncomfortable: “But when the lights went down, the spectators, Borges among them, are immersed once again in the fate of characters who traverse time, shivering once again at what we can call magic, for lack of a better word.”

Some Kind of Beautiful Signal’s broad array of international voices also includes an excerpt from Lydia Davis’s new translation of Madame Bovary, an excerpt from a never-before translated novel by Borges collaborator Adolfo Bioy Casares, and Susanna Fied’s latest translations from the Danish of poems by Inger Christensen.

Monday, December 13th, 2010

Below is the beginning of the poem “Dear Friend” by Dean Young. For more of his work, see here.

What will be served for our reception

in the devastation? Finger food, of course

and white wine, something printed on the napkins.

We were not children together

but we are now. Every bird knows

only two notes constantly rearranged.

Monday, December 13th, 2010

In a letter on behalf of poet Dean Young, Tony Hoagland details how Young has suffered from a degenerative heart condition for more than a decade, and how his condition has worsened “radically” in recent days. He’s in urgent need of a transplant. If he’s lucky enough to get one, there will be enormous costs involved, not nearly all of which will be paid by his health insurance. You can donate here. (Under the section labeled “Donation Information,” be sure to note that the donation is for Dean Young.)

In a letter on behalf of poet Dean Young, Tony Hoagland details how Young has suffered from a degenerative heart condition for more than a decade, and how his condition has worsened “radically” in recent days. He’s in urgent need of a transplant. If he’s lucky enough to get one, there will be enormous costs involved, not nearly all of which will be paid by his health insurance. You can donate here. (Under the section labeled “Donation Information,” be sure to note that the donation is for Dean Young.)

I have a close friend who was taught by Young at the University of Iowa’s graduate writing program a few years ago. He wrote to me over the weekend, in part: “Definitely encourage everyone you know to donate, he’s one of the good guys. One of the kindest, most encouraging writing teachers I ever had. And two of his books — First Course In Turbulence and Skid

and Skid — are two of the great volumes of poetry of the last 20 years.”

— are two of the great volumes of poetry of the last 20 years.”

Young’s nephew recently shared a letter that his uncle sent him in 1998. A piece:

I started writing poems in the third grade, and although I’m disappointed I’m not a lot better, it is something I do and therefore part of who I am, and cannot be reft from me. Perhaps I was too stupid or stoned or drunk or distracted or comfortable, or it was another world of skinny-dipping in the Bloomington quarries with a group of friends most of whom were trying to write well, with stupid jobs, and reading Frank O’Hara. I guess it was something I had faith in. It was later, by the time I was in graduate school, that the real ambitions (and poisons) of trying to get published and all that came into play. By then, well, it was too late. It was what I did. Remember, Seth, you can’t sustain inspiration, you can only court it, and here’s the thing: it happens WHILE you work. It’s not something to wait around for. You have to sweep the temple steps a lot in hopes that the god appears.

Please donate if you can.

Monday, December 13th, 2010

As I mentioned last week, The Millions was kind enough to ask me to participate in the site’s Year In Reading series. My entry went up over the weekend, and you can find it here. I start by saying, “It was mostly a year of some pleasant foothills in my reading life, and just one great peak.” I haven’t gotten around to writing about that peak at greater length for The Second Pass, but I hope to before too long.

Friday, December 10th, 2010

Sure, you can buy your friends and family safe books this holiday season; books you know they will “read” and “enjoy.” But why not spice up their library with, say, A Lust for Window Sills by Harry Mount?

Sure, you can buy your friends and family safe books this holiday season; books you know they will “read” and “enjoy.” But why not spice up their library with, say, A Lust for Window Sills by Harry Mount?

Last year around this time, I posted about the Weird Book Room at AbeBooks. Since then, the room has gotten larger — and weirder.

Some of the books are, understandably, already sold out. Those that flew off the shelf include Lumber Jack Songs with Yodel Arrangements, Atlas of the Fleas of Britain and Ireland, and The Romance of Proctology.

But there’s still plenty left for the special people on your list. Perhaps a lady friend would appreciate Playing the Tuba at Midnight: The Joys and Challenges of Singleness, a Christian-based perspective on loneliness into one’s 30s and beyond, or Menopop: A Menopause Pop-Up and Activity Book.

Or maybe you know a lot of do-it-yourself types. For them, there’s How to Make Your Own Shoes (OK, sounds practical), How to Start Your Own Country (I’m listening), and Make Your Own Sex Toys (egad).

History buffs? How about Soap Through the Ages or A Popular History of British Seaweeds by Rev. D. Landsborough, 400 pages that undoubtedly fly by.

There’s a lot more to choose from at the Weird Book Room. If you can spend less than an hour there, you’re stronger than I am.

Wednesday, December 8th, 2010

The Millions is in the middle of it annual series treat, A Year in Reading, in which various contributors recommend the best books they read this year, whether published in 2010 or not. The site’s been kind enough to ask me to participate the past two years. My entry is still to come, but there’s a lot up already: Lionel Shriver chooses to do God’s work and praises William Trevor, Dan Kois can’t resist choosing Freedom, Anthony Doerr admires a book that is both “a quest for the loneliest places in the world” and “a testament to the transformative power of maps,” Margaret Atwood recommends a book that’s been in print since it was published in 1860, and Emma Rathbone says one novel “fulfilled a need for British postwar spinster fiction I didn’t know I had.” . . . Jessica Francis Kane talks to Mark Doten about her debut novel, which will be reviewed here soon: “In the very beginning, it was a book set only in 1943. Then I saw Errol Morris’s Fog of War and realized I wanted to write about tragedy and how we remember tragedy.” . . . Christopher Graham profiles and interviews Lewis Lapham, who explains why he’s not approached more often by op-ed pages: “I’m not apt to know what I’m going to say, and they need people they can rely on. Your opinions have to be a commodity that can be trusted to measure up to the contents named on the box. You know what Rush Limbaugh’s going to say, you know what Paul Krugman’s going to say, and so on. God help them if they should change their minds.” . . . The Library of America’s blog recognizes Louisa May Alcott’s birthday, and approvingly quotes another source: “[Little Women is] something much better than ‘great’: it is beloved.” . . . Melville House asks if you can think of any authors “who have produced two great yet unalike works within a short period of time.” . . . As ever, Largehearted Boy is rounding up all of the year-end best-of lists you could want (and more).

The Millions is in the middle of it annual series treat, A Year in Reading, in which various contributors recommend the best books they read this year, whether published in 2010 or not. The site’s been kind enough to ask me to participate the past two years. My entry is still to come, but there’s a lot up already: Lionel Shriver chooses to do God’s work and praises William Trevor, Dan Kois can’t resist choosing Freedom, Anthony Doerr admires a book that is both “a quest for the loneliest places in the world” and “a testament to the transformative power of maps,” Margaret Atwood recommends a book that’s been in print since it was published in 1860, and Emma Rathbone says one novel “fulfilled a need for British postwar spinster fiction I didn’t know I had.” . . . Jessica Francis Kane talks to Mark Doten about her debut novel, which will be reviewed here soon: “In the very beginning, it was a book set only in 1943. Then I saw Errol Morris’s Fog of War and realized I wanted to write about tragedy and how we remember tragedy.” . . . Christopher Graham profiles and interviews Lewis Lapham, who explains why he’s not approached more often by op-ed pages: “I’m not apt to know what I’m going to say, and they need people they can rely on. Your opinions have to be a commodity that can be trusted to measure up to the contents named on the box. You know what Rush Limbaugh’s going to say, you know what Paul Krugman’s going to say, and so on. God help them if they should change their minds.” . . . The Library of America’s blog recognizes Louisa May Alcott’s birthday, and approvingly quotes another source: “[Little Women is] something much better than ‘great’: it is beloved.” . . . Melville House asks if you can think of any authors “who have produced two great yet unalike works within a short period of time.” . . . As ever, Largehearted Boy is rounding up all of the year-end best-of lists you could want (and more).

Wednesday, December 8th, 2010

My original plan was to write about Freedom in, say, four or five chunks, simply charting some of my responses to it as I went. That plan is out the window. Instead, I’m working on something longer about the book that I will post sometime before the holidays. In short, what happened is this: my reactions added up to a deep and honest bewilderment at the virtual unanimity of praise the book has received. On balance, I found it disappointing (and irritating) for almost exactly the same reasons I was underwhelmed by The Corrections. I’ve written before about the essay Franzen wrote for Harper’s that kick-started the best-selling phase of his career, and I’ve shared this excerpt from that essay, in which he’s talking about writing The Corrections:

My original plan was to write about Freedom in, say, four or five chunks, simply charting some of my responses to it as I went. That plan is out the window. Instead, I’m working on something longer about the book that I will post sometime before the holidays. In short, what happened is this: my reactions added up to a deep and honest bewilderment at the virtual unanimity of praise the book has received. On balance, I found it disappointing (and irritating) for almost exactly the same reasons I was underwhelmed by The Corrections. I’ve written before about the essay Franzen wrote for Harper’s that kick-started the best-selling phase of his career, and I’ve shared this excerpt from that essay, in which he’s talking about writing The Corrections:

The work of transparency and beauty and obliqueness that I wanted to write was getting bloated with issues. I’d already worked in contemporary pharmacology and TV and race and prison life and a dozen other vocabularies; how was I going to satirize Internet boosterism and the Dow Jones as well while leaving room for the complexities of character and locale?

Needless to say, I don’t think he solved this problem in The Corrections, and he exacerbated it in Freedom. More soon…

Monday, December 6th, 2010

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

If you were to ask for a list of my favorite writers, you might hear a name or two before you heard William Trevor. You might not. Charles McGrath reviews the new collection of Trevor’s short stories: “His voice, wise and omniscient, sometimes sounds like the ancient voice of storytelling itself. . . . he is less interested in the way things change than in the way they don’t. . . . Trevor’s prose has a precise, well-made solidness that is itself a kind of protest against change.” . . . Peter Duffy reviews “a sturdy and unsentimental tale of how Ireland reached its current predicament, written by an American journalist who specializes in the global economy.” . . . John Paul Stevens reviews David Garland’s new book about the death penalty in America: “Some of his eminently readable prose reminds me of Alexis de Tocqueville’s nineteenth-century narrative about his visit to America; it has the objective, thought-provoking quality of an astute observer rather than that of an interested participant in American politics.” . . . Richard Pious has high praise for Edmund Morris’ third and final installment of his Theodore Roosevelt biography: “Colonel Roosevelt, with its descriptive and narrative power, its thorough exploitation of sources, and its interplay of man and nation, may be the best biography ever written about the life of an American president.” . . . Caroline Weber admires Fame, Tom Payne’s “trenchant, unsettling, darkly hilarious” new book about celebrity both ancient and modern: “Moving seamlessly between yesterday’s great literature — Greek, Roman, early Christian, Enlightenment and Romantic — and today’s trashy tabloids, Payne advances a persuasive, if disturbing, definition of what fame is now, and what it has ever been.”

If you were to ask for a list of my favorite writers, you might hear a name or two before you heard William Trevor. You might not. Charles McGrath reviews the new collection of Trevor’s short stories: “His voice, wise and omniscient, sometimes sounds like the ancient voice of storytelling itself. . . . he is less interested in the way things change than in the way they don’t. . . . Trevor’s prose has a precise, well-made solidness that is itself a kind of protest against change.” . . . Peter Duffy reviews “a sturdy and unsentimental tale of how Ireland reached its current predicament, written by an American journalist who specializes in the global economy.” . . . John Paul Stevens reviews David Garland’s new book about the death penalty in America: “Some of his eminently readable prose reminds me of Alexis de Tocqueville’s nineteenth-century narrative about his visit to America; it has the objective, thought-provoking quality of an astute observer rather than that of an interested participant in American politics.” . . . Richard Pious has high praise for Edmund Morris’ third and final installment of his Theodore Roosevelt biography: “Colonel Roosevelt, with its descriptive and narrative power, its thorough exploitation of sources, and its interplay of man and nation, may be the best biography ever written about the life of an American president.” . . . Caroline Weber admires Fame, Tom Payne’s “trenchant, unsettling, darkly hilarious” new book about celebrity both ancient and modern: “Moving seamlessly between yesterday’s great literature — Greek, Roman, early Christian, Enlightenment and Romantic — and today’s trashy tabloids, Payne advances a persuasive, if disturbing, definition of what fame is now, and what it has ever been.”

Thursday, December 2nd, 2010

I’ve finally taken the plunge into Freedom, and since every magazine, newspaper, blog, wire service, and children’s lemonade stand has reviewed it already, I figured I would blog about it in pieces rather than offer a more formal review. I was partly inspired to tackle it now because the most recent issue of n+1 offers reactions to the novel by four of the magazine’s editors, and I’m interested to read those after finishing the book.

I’ve finally taken the plunge into Freedom, and since every magazine, newspaper, blog, wire service, and children’s lemonade stand has reviewed it already, I figured I would blog about it in pieces rather than offer a more formal review. I was partly inspired to tackle it now because the most recent issue of n+1 offers reactions to the novel by four of the magazine’s editors, and I’m interested to read those after finishing the book.

I’m through the first 187 pages, a section called “Good Neighbors.” (I’m actually through more than that, but for the purposes of this post, let’s pretend.) So far, so . . . not bad. No major hiccups of forced social relevance, which more than anything else ruined The Corrections. (You don’t need reminding, but just in case: the sudden prolonged rants about the pharmaceutical industry, everything about Lithuania and the Internet, etc.)

A very quick plot synopsis for those who need it: Walter and Patty Berglund live in St. Paul, Minnesota, with their two teenage children, Joey and Jessica. This first section details their lives together (including Patty’s almost obsessive relationship with her son, which is more insisted upon by Franzen than actually demonstrated), and flashes back to Walter and Patty’s time in college, when she was a standout basketball player and he was the nerdy friend of Richard Katz, an edgy and alluring musician who looks, we’re told, like Muammar el-Qaddafi.

Through nearly 200 pages, I haven’t underlined or otherwise noted a single sentence or passage that I would want to return to or share with someone. Perhaps this is an old-fashioned desire, but it’s one I feel strongly while reading. And it’s not to say Franzen is a bad writer — this first section, like everything else I’ve ever read by him, went down quite smoothly. It’s just that his prose is not particularly stylish or profound. I felt a similar lack in The Corrections, though it seems even more pronounced so far in Freedom.

There’s also an odd decision in this first section. The great majority of it is offered in the form of an autobiography that Patty is writing: “(Composed at Her Therapist’s Suggestion).” Others have noted that Patty writes in a way the actual character of Patty almost certainly wouldn’t, and that’s what I expected would annoy me about this section. And it did, a little. The reason it didn’t annoy me more is because it’s so easy to forget the conceit and just read her sections as more all-seeing narrator. For one thing, Patty never refers to herself in the first person: “The regrettable truth is that Patty had soon come to find sex sort of boring and pointless — the same old sameness — and to do it mostly for Walter’s sake.”

And in addition to writing in certain specific ways that are Franzen-like, her entire approach to viewing her life is much broader, more psychologically probing of herself and others, than almost any normal person would be in such an exercise. She’s writing like a novelist, which is a slightly different complaint than saying she’s writing like a very good writer. So my annoyance was not with her voice itself, but with the very decision to say it’s her voice — if the section is in third person, and it’s focusing on several characters through the perspective of the book’s ostensible protagonist to this point, why even roll out the gimmick in the first place? Perhaps this will be answered later, but for now it’s a mystery.

I don’t mean to sound so sour about this first section. It wasn’t earth-shattering (by a long shot), but it has me eager to continue, with hopes of finding out what the fuss is about.

Tuesday, November 30th, 2010

Akashic Books asked 20 different book blogs to each review one story from Joe Meno’s collection Demons in the Spring, which was published earlier this year in paperback. I chose to review “Art School Is Boring So.” The story was illustrated by Steph Davidson.

Meno wastes no time establishing the informal, disaffected attitude of this story’s protagonist: “Art school is boring so Audrey wears a space helmet around: It is kind of pretentious but so what.”

Meno wastes no time establishing the informal, disaffected attitude of this story’s protagonist: “Art school is boring so Audrey wears a space helmet around: It is kind of pretentious but so what.”

The helmet was an art project, but Audrey wears it now mostly so she doesn’t have to hear her “slutbag” roommate, Isobel, having sex in the next room over. Isobel is a dancer who has posted naked pictures of herself online, the extroverted opposite of Audrey, who sullenly walks around planning to make various zines, one of which involves the fictional solid waste of celebrities: “She has at least a thousand different ideas for zines she could do: One might be about Hall & Oates, one could be about sea horses, one about how she is starting to like soul music, and one all about fireworks. The problem is, well, she just hasn’t had time to start any of them.”

Audrey is a daydreamer, though her imaginings are blunt, not particularly . . . imaginative. She shows interest in the people around her, including an old Japanese couple that lives next door, but her emotional range is mostly limited to her own pedestrian internal concerns about art and boys. She seems capable of being funny or clever on occasion with others, but Meno mostly positions her as a sad cliche:

Like everyone else in art school, she hates U.S. imperialism. She hates mass production but she secretly likes Britney Spears. . . . She hates all the white leather belts she sees people wearing but wears one anyway. She hates that all modern art has to be explained. She hates the kind of drawings she makes because she cannot draw people’s faces. She hates that her parents are rich and she hates that she hates them for being rich.”

This is not to say the story is unsuccessful. Meno accurately depicts the type of young person turned off by who knows what — unloving parents, too much cultural noise, the communicative restrictions of social networks. As an exercise in sketching character, “Art School Is Boring So” works, but given the limits of that character’s complexity and charms, there is something necessarily limited about the story.

It seems almost certain that Meno is hoping to elicit some minimum of sympathy for Audrey. And there is something naive, lonely, and sad about her, much like the artwork that accompanies the story. She is more pathetic than repellent. But some characters in stories, even those who are pathetic or worse, can be easily imagined in a longer work, where a reader would gladly follow them for a while. Audrey, for this reader, is very much not one of those characters. She is a well drawn but somewhat irritating presence, effectively summed up in these few pages.

Monday, November 29th, 2010

I’ve always assumed I would dislike the work of Michel Houellebecq, not just because negative reviews of it include lines like, “What is surprising about the book is not its pessimism but the fantastically boring way it has been couched,” but because positive reviews include lines like, “His vision of a post-existentialist, rationalist world, in which any attempts at human happiness are not only doomed but risibly beside the point, is completely without mitigation.”

I’ve always assumed I would dislike the work of Michel Houellebecq, not just because negative reviews of it include lines like, “What is surprising about the book is not its pessimism but the fantastically boring way it has been couched,” but because positive reviews include lines like, “His vision of a post-existentialist, rationalist world, in which any attempts at human happiness are not only doomed but risibly beside the point, is completely without mitigation.”

Yet, I found the interview with Houellebecq in the most recent issue of The Paris Review entertaining, even charming in a way. If the nihilism of his novels comes off like the nihilism of his interview, I might be OK with it. Here he is on his critics. His point about readers’ relationships with characters is one I agree with completely:

Interviewer: You’ve said book reviewers don’t focus enough on the characters.

Houellebecq: One precious thing about ordinary readers is that sometimes they develop feelings for the characters. This is something critics never discuss. Which is a shame. The Anglo-Saxon critics do good plot summaries but they don’t talk about the characters either. Readers, however, do it uninhibitedly.

Interviewer: What about your critics? Can you just sum up briefly what you hold against the French press?

Houellebecq: First of all, they hate me more than I hate them. What I do reproach them for isn’t bad reviews. It is that they talk about things having nothing to do with my books — my mother or my tax exile — and that they caricature me so that I’ve become a symbol of so many unpleasant things — cynicism, nihilism, misogyny. People have stopped reading my books because they’ve already got their idea about me. To some degree of course, that’s true for everyone. After two or three novels, a writer can’t expect to be read. The critics have made up their minds.

Tuesday, November 23rd, 2010

The recent wave of true crime around here is almost over (for now). I’m finishing up Helter Skelter, at which point I think I’m going to read exclusively about bunny rabbits for a year or so. Really, really cute bunny rabbits — not those average-looking ones. And certainly not this one.

Toward the end of Helter Skelter, mention is made of “Decline of the English Murder,” a 1946 essay by George Orwell that considers the particulars of the ideal murder story for the leisurely reader. (”Your pipe is drawing sweetly, the sofa cushions are soft underneath you, the fire is well alight, the air is warm and stagnant. In these blissful circumstances, what is it that you want to read about?”) A piece:

[L]et me try to define what it is that the readers of Sunday papers mean when they say fretfully that “you never seem to get a good murder nowadays”.

In considering the nine murders I named above, one can start by excluding the Jack the Ripper case, which is in a class by itself. Of the other eight, six were poisoning cases, and eight of the ten criminals belonged to the middle class. In one way or another, sex was a powerful motive in all but two cases, and in at least four cases respectability—the desire to gain a secure position in life, or not to forfeit one’s social position by some scandal such as a divorce—was one of the main reasons for committing murder. In more than half the cases, the object was to get hold of a certain known sum of money such as a legacy or an insurance policy, but the amount involved was nearly always small. In most of the cases the crime only came to light slowly, as the result of careful investigations which started off with the suspicions of neighbors or relatives; and in nearly every case there was some dramatic coincidence, in which the finger of Providence could be clearly seen, or one of those episodes that no novelist would dare to make up, such as Crippen’s flight across the Atlantic with his mistress dressed as a boy, or Joseph Smith playing “Nearer, my God, to Thee” on the harmonium while one of his wives was drowning in the next room. The background of all these crimes, except Neill Cream’s, was essentially domestic; of twelve victims, seven were either wife or husband of the murderer.

With all this in mind one can construct what would be, from a News of the World reader’s point of view, the “perfect” murder. . . .

Tuesday, November 23rd, 2010

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Judith Shulevitz reads the collected New Yorker stories of Ann Beattie, who famously helped to define the magazine’s fiction aesthetic in the 1970s: “Beattie was simultaneously reporting on and satirizing her generation. She understood its elaborate alienation and self-pity; she heard, beneath the jaded, post-1960s self-mockery, the hope that nontraditional lifestyle choices were still viable, and the fear that they weren’t.” . . . Second Pass contributor Jon Fasman reviews Salman Rushdie’s latest: “I found it nearly impossible to race past the cloyingly false childishness, the canned sense of expectation that the first chapter sets up. Reader, persist.” . . . Glenn Lester reviews Jim Hanas’ collection of short stories: “Why They Cried is, in fact, about something important: how much suffering arises in the gap between our constructed public identities and whatever kernel of self is left inside.” . . . John Self looks back at The Street of Crocodiles by Bruno Schulz, in the news lately thanks to Jonathan Safran Foer’s latest project. . . . Rachel Cooke marvels at the car-wreck memoir of a Guinness heiress and the stepdaughter of poet Robert Lowell: “Sometimes, even truly bad books can be gripping, and Ivana Lowell’s Why Not Say What Happened? is one of them. Clunky, repetitive and disorganized . . . her prose is also fatally hamstrung by the weird incontinent blankness that is so typical of those who have spent too long in rehab. . . . she kills her funniest anecdotes at 100 paces; her metaphors are so bad, they make you cry out in pain. And yet I could not put her book down. Never before has so much bad behavior by people who should have known better been crammed into so few pages.”

Judith Shulevitz reads the collected New Yorker stories of Ann Beattie, who famously helped to define the magazine’s fiction aesthetic in the 1970s: “Beattie was simultaneously reporting on and satirizing her generation. She understood its elaborate alienation and self-pity; she heard, beneath the jaded, post-1960s self-mockery, the hope that nontraditional lifestyle choices were still viable, and the fear that they weren’t.” . . . Second Pass contributor Jon Fasman reviews Salman Rushdie’s latest: “I found it nearly impossible to race past the cloyingly false childishness, the canned sense of expectation that the first chapter sets up. Reader, persist.” . . . Glenn Lester reviews Jim Hanas’ collection of short stories: “Why They Cried is, in fact, about something important: how much suffering arises in the gap between our constructed public identities and whatever kernel of self is left inside.” . . . John Self looks back at The Street of Crocodiles by Bruno Schulz, in the news lately thanks to Jonathan Safran Foer’s latest project. . . . Rachel Cooke marvels at the car-wreck memoir of a Guinness heiress and the stepdaughter of poet Robert Lowell: “Sometimes, even truly bad books can be gripping, and Ivana Lowell’s Why Not Say What Happened? is one of them. Clunky, repetitive and disorganized . . . her prose is also fatally hamstrung by the weird incontinent blankness that is so typical of those who have spent too long in rehab. . . . she kills her funniest anecdotes at 100 paces; her metaphors are so bad, they make you cry out in pain. And yet I could not put her book down. Never before has so much bad behavior by people who should have known better been crammed into so few pages.”

Friday, November 19th, 2010

Dan Wagstaff interviews book designer Clare Skeats. (“Its always a thrill to get asked to do a classic. I also like first-time authors (as there’s no baggage), and books about really odd subjects: invisible dogs, menopause, suicide, unicorns … bring it on.”) . . .James Morrison interviews Nick Morley, an artist who works with linocuts and etchings and is getting more involved in book illustration. . . . Maud Newton packs a lot of interesting objects onto her spare, neatly organized desk. . . . Publisher Scott Pack has an idea this site can get behind: The Library of Lost Books. . . . The Paris Review talks to Christopher Sorrentino about his entry in a new series of books about popular films. Sorrentino wrote about Death Wish. In the interview, The French Connection is mentioned, and Sorrentino says, “I really don’t like that movie.” Does. Not. Compute. . . . Jonathan Safran Foer has a new book coming out in January. It’s really an old book, The Street of Crocodiles by Bruno Schulz, literally cut up into a new book by Foer. The production looks quite innovative. Foer’s discussion of it, unsurprisingly, is quite precious. (”Q: What is it about the die-cutting method that appealed to you? A: That’s like saying to somebody, ‘What about the way that you just kissed me was good?’”) . . . In the wake of Patti Smith winning the National Book Award, Macy Halford links to a profile of the musician and writer in The New Yorker.

Dan Wagstaff interviews book designer Clare Skeats. (“Its always a thrill to get asked to do a classic. I also like first-time authors (as there’s no baggage), and books about really odd subjects: invisible dogs, menopause, suicide, unicorns … bring it on.”) . . .James Morrison interviews Nick Morley, an artist who works with linocuts and etchings and is getting more involved in book illustration. . . . Maud Newton packs a lot of interesting objects onto her spare, neatly organized desk. . . . Publisher Scott Pack has an idea this site can get behind: The Library of Lost Books. . . . The Paris Review talks to Christopher Sorrentino about his entry in a new series of books about popular films. Sorrentino wrote about Death Wish. In the interview, The French Connection is mentioned, and Sorrentino says, “I really don’t like that movie.” Does. Not. Compute. . . . Jonathan Safran Foer has a new book coming out in January. It’s really an old book, The Street of Crocodiles by Bruno Schulz, literally cut up into a new book by Foer. The production looks quite innovative. Foer’s discussion of it, unsurprisingly, is quite precious. (”Q: What is it about the die-cutting method that appealed to you? A: That’s like saying to somebody, ‘What about the way that you just kissed me was good?’”) . . . In the wake of Patti Smith winning the National Book Award, Macy Halford links to a profile of the musician and writer in The New Yorker.

Thursday, November 18th, 2010

Jaimy Gordon’s Lord of Misrule

Jaimy Gordon’s Lord of Misrule was awarded the National Book Award for Fiction tonight. It’s the second time this year that a high-profile fiction award has gone to a previously very-low-profile novel. (Paul Harding’s Tinkers won the Pulitzer in April.)

was awarded the National Book Award for Fiction tonight. It’s the second time this year that a high-profile fiction award has gone to a previously very-low-profile novel. (Paul Harding’s Tinkers won the Pulitzer in April.)

I’m particularly eager to read Lord of Misrule because I’m a fan of horse racing, and Gordon’s novel is set at a fictional track in West Virginia. In the lead-up to the NBA announcement, Andrew Beyer raved about the book in the Daily Racing Form, not the usual place for fiction recommendations:

There are no triumph-of-the-underdog moments in author Jaimy Gordon’s book. Her mythical Indian Mound Downs is populated by infirm, battle-scarred old horses and the owners, grooms, and trainers who try to eke out a living with them. Some of the characters are noble, in their way, some deranged, some capable of murder and rape, but few of them harbor dreams much grander than winning a cheap race, collecting a small purse, and perhaps cashing a bet.

(Beyer, a Harvard graduate, has played a starring role in modern horse racing.)

In this interview with Gordon from “circa 1983,” which appeared in Gargoyle Magazine and featured the photo above, she was asked about the commercial prospects of a novel she was working on at the time, and her answer included this:

Now let me ask you a question. What do you mean by “commercial”? I suspect you mean marketable to trade presses, establishment publishing, New York, the big time. But all the novelists who publish with New York presses are hardly commercial in the financial sense of the word; often their books sell no more copies than they would with the older small presses.

Very true. And Gordon’s little-press book will now sell more than many giant-press offerings do. (A major publisher has already bought the paperback rights to Misrule as well as the rights to Gordon’s next book.) The Wall Street Journal was one of several outlets to note just how modest Gordon’s current publisher, McPherson & Co., is:

Bruce McPherson, publisher and owner, normally prints 2,000 copies of a new book. However, after the nomination was announced, Barnes & Noble alone wanted 2,000 copies. Mr. McPherson decided to print 8,000. “It’s a gamble that I’m not used to taking,” he said. . . . Back in 1974, the first book that he published was Ms. Gordon’s debut novel, Shamp of the City-Solo. Like her subsequent two novels, 1990’s She Drove Without Stopping and 1999’s Bogeywoman, it received good reviews but never found a large audience.

If Gordon’s win puts you in the mood for other books about the sport, I recommend William Nack’s Secretariat (now with unfortunate movie tie-in cover, but such is life), John Jeremiah Sullivan’s Blood Horses

(now with unfortunate movie tie-in cover, but such is life), John Jeremiah Sullivan’s Blood Horses , and Joe Palmer’s This Was Racing

, and Joe Palmer’s This Was Racing , which I wrote about earlier this year.

, which I wrote about earlier this year.

Tuesday, November 16th, 2010

As I wrote in my review of Ann Rule’s book about Ted Bundy on the Backlist this week, I’m currently reading Helter Skelter, and had planned to read Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song after that.

To my shock, it seems that Mailer’s book is out of print. It’s a novelization of the life of murderer Gary Gilmore, who requested to be executed by firing squad. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1980, and the only book I think of more quickly (maybe) when I hear Mailer’s name is The Naked and the Dead. So why is The Executioner’s Song out of print? I have no idea.

Tuesday, November 16th, 2010

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

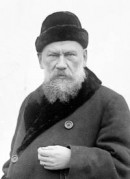

Upon the publication of a new anthology of Irish short stories (to be published in the U.S. in March), Keith Hopper surveys the history of such anthologies and the history of attempts to explain why the Irish thrive in the form. . . . Zadie Smith on some movie about Facebook and a book about technology — but really, Zadie Smith, brilliantly, on our impoverished lives. . . . Geoff Dyer reviews My Prizes, in which Thomas Bernhard writes about the awards he reluctantly received: “The pieces in My Prizes are nice anecdotes, with some wonderful riffs, but they don’t have the aesthetic shape or inner propulsion to amount to more than that.” . . . Vivian Gornick examines the marriage of Leo and Sophia Tolstoy: “Neither could have understood in advance of the marriage the depth of emotional ambition that motivated them, much less that it was precisely because that ambition was destined to be thwarted that each would be bound permanently, one to the other. It was the stuff upon which Sigmund Freud was to build an intellectual empire.” . . . Adam Bradley says Jay-Z’s first book may leave readers “dissatisfied with the level of revelation and reflection,” but it showcases the lyrics of rap in a refreshing way.

Upon the publication of a new anthology of Irish short stories (to be published in the U.S. in March), Keith Hopper surveys the history of such anthologies and the history of attempts to explain why the Irish thrive in the form. . . . Zadie Smith on some movie about Facebook and a book about technology — but really, Zadie Smith, brilliantly, on our impoverished lives. . . . Geoff Dyer reviews My Prizes, in which Thomas Bernhard writes about the awards he reluctantly received: “The pieces in My Prizes are nice anecdotes, with some wonderful riffs, but they don’t have the aesthetic shape or inner propulsion to amount to more than that.” . . . Vivian Gornick examines the marriage of Leo and Sophia Tolstoy: “Neither could have understood in advance of the marriage the depth of emotional ambition that motivated them, much less that it was precisely because that ambition was destined to be thwarted that each would be bound permanently, one to the other. It was the stuff upon which Sigmund Freud was to build an intellectual empire.” . . . Adam Bradley says Jay-Z’s first book may leave readers “dissatisfied with the level of revelation and reflection,” but it showcases the lyrics of rap in a refreshing way.

Monday, November 15th, 2010

A continuing series that highlights books recently acquired by publishing houses for future release. Each post features a book we’re looking forward to, and a book we’re . . . not.

The Cherry:

Mitchell Duneier and Alice Goffman’s Ghetto: The Invention of a Place, the Spread of an Idea, a brief, pointed account of the ghetto as a contested place and idea — in early modern Rome and Venice; in the Jewish immigrant colonies of early 20th-century America; in Nazi Germany; in Chicago after the great migration; in the neighborhoods that spawned hip-hop; in Muslim communities across Europe; and in Gaza; a largely unknown story of a concrete place and a controversial notion with consequences.

The Pit:

Robert Vetere and Valerie Andrews’ From Wags to Riches: How to Succeed in Business by Unleashing Your Inner Dog, how to motivate others — as well as yourself — by unleashing your inner dog; tap into your own “canine IQ” and discover why man’s best friend is rapidly emerging as the new executive and life coach.

Friday, November 12th, 2010

I keep meaning to post a Backlist feature about a book about Ted Bundy to complement the recent review of The Killer of Little Shepherds, but this will now have to happen tomorrow, for various logistical reasons. The Shelf will likely be updated over the weekend, too. So, just a note that there will be some rare Saturday action on the site, should you be interested.

Friday, November 12th, 2010

Many thanks to everyone who made it out to Melville House on Wednesday night for this site’s first public event. The store was beautifully put together for it, the crowd was large (and exceedingly polite during the readings), and the readers—Carlene Bauer, Will Blythe, Maud Newton, Jason Zinoman, and Lauren Kaminsky—were fantastic.

I left my camera on a table the whole night, but if you’d like to see some snaps, Electric Literature was there to cover the event—a pleasant surprise.

My hope is to have another celebratory night in mid-March, to mark the site’s two-year anniversary. (Wednesday night was the 20-month anniversary, but that was truly an unplanned coincidence.) I’ll keep you posted if and as details emerge.

Friday, November 12th, 2010

From The Loser by Thomas Bernhard:

by Thomas Bernhard:

sat at the table by the window where I used to sit in past years, but it didn’t seem to me that time had stood still. I heard the innkeeper working in the kitchen and I thought she was probably making lunch for her child who had came home from school at one or two, warming up some goulash or perhaps some vegetable soup. In theory we understand people, but in practice we can’t put up with them, I thought, deal with them for the most part reluctantly and always treat them from our own point of view. We should observe and treat people not from our point of view but from all angles, I thought, associate with them in such a way that we can say we associate with them so to speak in a completely unbiased way, which however isn’t possible, since we actually are always biased against everybody.

Wednesday, November 10th, 2010

Tonight, we party.

Well, first we politely listen to terrific readers, and then we party.

At 7:30 tonight, The Second Pass hosts a night at Melville House Bookstore in Brooklyn. Those readers are Carlene Bauer, Will Blythe, Maud Newton, and Jason Zinoman. (For more about them, see here. And, Maud will not be showing up empty-handed.) There will be wine and snacks.

For directions, see here.

Monday, November 8th, 2010

On the 100th anniversary of Leo Tolstoy’s death, The Atlantic digs out an 1891 profile of him from its archives. . . . Craig Fehrman profiles historian Jill Lepore for the Boston Globe on the occasion of her new book about the Tea Party. He writes a follow-up post, about other historians’ opinions of Lepore, on his blog. . . . Carlene Bauer writes about Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Rilke, Simone Weil, and religious doubt. . . . Belated birthday wishes for D.G. Myers’ A Commonplace Blog, which recently turned two. Myers also recently linked to a piece reconsidering a 1978 novel by Stanley Crawford; a novel with the amazing title Some Instructions to my Wife Concerning the Upkeep of the House and Marriage, and to my Son and Daughter, Concerning the Conduct of their Childhood. The book deals, in part, with metaphors for marriage, as does another Crawford book that I wrote about here a while back. . . . Pauline Kael on not watching a movie more than once. . . . A San Francisco newspaper sent Dave Eggers to the World Series with a sketchbook. This is what he saw. . . . A bit of philosophy to round things out: 91-year-old Mary Midgley has a must-read at The New Humanist called “Against Humanism.” I found it provocative, clear, and pithy: “Materialists take matter to be what is typically real, but matter itself is not at all what it used to be.” I’m strongly agnostic myself, but have to bristle (yet again) at the smug shallowness of today’s atheists, some of whom quickly dismiss Midgley’s work in the comments.

On the 100th anniversary of Leo Tolstoy’s death, The Atlantic digs out an 1891 profile of him from its archives. . . . Craig Fehrman profiles historian Jill Lepore for the Boston Globe on the occasion of her new book about the Tea Party. He writes a follow-up post, about other historians’ opinions of Lepore, on his blog. . . . Carlene Bauer writes about Tess of the D’Urbervilles, Rilke, Simone Weil, and religious doubt. . . . Belated birthday wishes for D.G. Myers’ A Commonplace Blog, which recently turned two. Myers also recently linked to a piece reconsidering a 1978 novel by Stanley Crawford; a novel with the amazing title Some Instructions to my Wife Concerning the Upkeep of the House and Marriage, and to my Son and Daughter, Concerning the Conduct of their Childhood. The book deals, in part, with metaphors for marriage, as does another Crawford book that I wrote about here a while back. . . . Pauline Kael on not watching a movie more than once. . . . A San Francisco newspaper sent Dave Eggers to the World Series with a sketchbook. This is what he saw. . . . A bit of philosophy to round things out: 91-year-old Mary Midgley has a must-read at The New Humanist called “Against Humanism.” I found it provocative, clear, and pithy: “Materialists take matter to be what is typically real, but matter itself is not at all what it used to be.” I’m strongly agnostic myself, but have to bristle (yet again) at the smug shallowness of today’s atheists, some of whom quickly dismiss Midgley’s work in the comments.

Monday, November 8th, 2010

This may have been published a while ago, but this weekend was the first time I came across Jonathan Franzen’s elegy for David Foster Wallace from October 2008. A piece:

I’d loved Dave from the very first letter I ever got from him, but the first two times I tried to meet him in person, up in Cambridge, he flat-out stood me up. Even after we did start hanging out, our meetings were often stressful and rushed—much less intimate than exchanging letters. Having loved him at first sight, I was always straining to prove that I could be funny enough and smart enough, and he had a way of gazing off at a point a few miles distant which made me feel as if I were failing to make my case. Not many things in my life ever gave me a greater sense of achievement than getting a laugh out of Dave.

Monday, November 1st, 2010

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

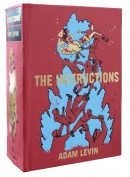

I don’t know if you’ve seen Adam Levin’s debut novel, The Instructions, in stores yet, but it is a monster, the thickest brick of a book that I’ve seen in some time. Maud Newton says it’s worth the possible back pain to pick it up: “[L]ike Roth’s and Vonnegut’s, Levin’s flights of fancy are placed in service of a deadly serious project. Not only is he, as he recently told The Chicago Tribune, having “a conversation with Jewish literature,” he’s illustrating, in a wholly original way, exactly what sort of catastrophe results when fervent religious conviction meets brute force.” . . . Tim Parks reviews Philip Roth’s latest, and really his last several books. About the latest, Nemesis he says, “so brazenly are we thrust towards this textbook enigma that readers may find themselves more intrigued by the author’s loyalty to tired literary stratagems than interested in the fate of characters who were never much more than pieces on a chessboard.” . . . Jed Perl on the New York stories of Elizabeth Hardwick: “Hardwick’s stories have the potency of metropolitan fairytales. It is the eloquence of certain images, characters, and actions that holds us, while the meanings or morals to be drawn from these adventures remain just beyond our reach.” . . . Steven Shapin reviews The Emperor of All Maladies, oncologist Siddhartha Mukherjee’s sprawling story of cancer, “a history of the disease and of the attempts to describe it, explain it, manage it, and cure it, or just to reconcile its victims to their fate.” . . . Philip Caputo reviews Bruce Machart’s “impressive” debut novel: “Machart has dared to park his wagon on the tracks of the Desert Limited and managed not to get flattened by [Cormac] McCarthy’s locomotive.” . . . Evelyn McDonnell says that Sara Marcus’ history of the Riot Grrrl movement “puts into printed narrative a much misunderstood and maligned but crucial piece of the feminist past.”

I don’t know if you’ve seen Adam Levin’s debut novel, The Instructions, in stores yet, but it is a monster, the thickest brick of a book that I’ve seen in some time. Maud Newton says it’s worth the possible back pain to pick it up: “[L]ike Roth’s and Vonnegut’s, Levin’s flights of fancy are placed in service of a deadly serious project. Not only is he, as he recently told The Chicago Tribune, having “a conversation with Jewish literature,” he’s illustrating, in a wholly original way, exactly what sort of catastrophe results when fervent religious conviction meets brute force.” . . . Tim Parks reviews Philip Roth’s latest, and really his last several books. About the latest, Nemesis he says, “so brazenly are we thrust towards this textbook enigma that readers may find themselves more intrigued by the author’s loyalty to tired literary stratagems than interested in the fate of characters who were never much more than pieces on a chessboard.” . . . Jed Perl on the New York stories of Elizabeth Hardwick: “Hardwick’s stories have the potency of metropolitan fairytales. It is the eloquence of certain images, characters, and actions that holds us, while the meanings or morals to be drawn from these adventures remain just beyond our reach.” . . . Steven Shapin reviews The Emperor of All Maladies, oncologist Siddhartha Mukherjee’s sprawling story of cancer, “a history of the disease and of the attempts to describe it, explain it, manage it, and cure it, or just to reconcile its victims to their fate.” . . . Philip Caputo reviews Bruce Machart’s “impressive” debut novel: “Machart has dared to park his wagon on the tracks of the Desert Limited and managed not to get flattened by [Cormac] McCarthy’s locomotive.” . . . Evelyn McDonnell says that Sara Marcus’ history of the Riot Grrrl movement “puts into printed narrative a much misunderstood and maligned but crucial piece of the feminist past.”

Thursday, October 28th, 2010

Readers of a certain musical bent will likely be charmed by these prints imagining songs by The Smiths as vintage Penguin paperbacks. . . . A fun interview with Jonathan Lethem about movies: his new book about the cult classic They Live, his opinion of Christopher Nolan’s movies, and which of his novels David Cronenberg has shown interest in bringing to the screen. . . . Patrick Kurp shares more than one piece of wisdom from Marianne Moore in a piece she wrote called “If I Were Sixteen Today” when she was 70. . . . Learn why, “You should avoid the culture pages of the New Yorker if you are a teenage boy already terrified that you’re never going to have sex.” . . . I don’t have any interest in actually reading this, but seeing as how my undefeated fantasy football team is named the Fighting Roger Sterlings, I feel obligated to pass it on. . . . Dinaw Mengestu talks to the Paris Review about his new novel. (“I wanted to show how two people can be attached to each another and still feel completely alienated.”) . . . Not technically book-related, but still amazing: In 1916, a respected engineer and urban planner proposed “A Really Greater New York” in an article for Popular Science. The plan included filling in the East River.

Readers of a certain musical bent will likely be charmed by these prints imagining songs by The Smiths as vintage Penguin paperbacks. . . . A fun interview with Jonathan Lethem about movies: his new book about the cult classic They Live, his opinion of Christopher Nolan’s movies, and which of his novels David Cronenberg has shown interest in bringing to the screen. . . . Patrick Kurp shares more than one piece of wisdom from Marianne Moore in a piece she wrote called “If I Were Sixteen Today” when she was 70. . . . Learn why, “You should avoid the culture pages of the New Yorker if you are a teenage boy already terrified that you’re never going to have sex.” . . . I don’t have any interest in actually reading this, but seeing as how my undefeated fantasy football team is named the Fighting Roger Sterlings, I feel obligated to pass it on. . . . Dinaw Mengestu talks to the Paris Review about his new novel. (“I wanted to show how two people can be attached to each another and still feel completely alienated.”) . . . Not technically book-related, but still amazing: In 1916, a respected engineer and urban planner proposed “A Really Greater New York” in an article for Popular Science. The plan included filling in the East River.

Thursday, October 28th, 2010

From The Dark by John McGahern:

by John McGahern:

You couldn’t be a priest, never now, that was all. You’d never raise anointed hands. You’d drift into the world, world of girls and women, company in gay evenings, exact opposite of the lonely dedication of the priesthood unto death. Your life seemed set, without knowing why, it was fixed, you had no choice. You were a drifter, you’d drift a whole life long after pleasure, but at the end there’d be the reckoning. If you could be a priest you’d be able to enter that choking moment without fear, you’d have already died to longing, you’d have already abandoned the world for that reality, there’d be no confusion. But the night and room and your father and even the hedge around the orchard at home were all confusion, there was no beginning nor end.

Monday, October 25th, 2010

A weekly roundup of noteworthy reviews from other sources.

Dwight Garner says that Avi Steinberg’s Running the Books, which recounts the author’s time as a prison librarian in Boston, “gets off to an obnoxious start,” reading mostly like a “hopped-up” gimmick. But according to Garner, the gimmick deepens into something much more: “Mr. Steinberg’s sentences start to pop out at you, at first because they’re funny and then because they’re acidly funny. The book slows down. It blossoms. Mr. Steinberg proves to be a keen observer, and a morally serious one. His memoir is wriggling and alive — as involving, and as layered, as a good coming-of-age novel.” . . . Maile Meloy makes Thomas McGuane’s latest sound like a lot of fun, even if it’s a bit sloppy in squaring all the facts of its fictional world: “As with McGuane’s earlier novels, the rambling plot is sustained because the individual episodes are a pleasure, often farcical and always acutely observed, and because the hero is sympathetic in his dissociated journey.” . . . Patrick Marnham reviews Pedigree, the “lengthy but little-read autobiographical novel” by Georges Simenon, “a Dickensian portrait, with poverty, crime, lunacy, wealth, corruption, and mockery, but a complete absence of Dickensian sentimentality.” . . . Jay Parini has written novels about Tolstoy, Walter Benjamin, and now, Herman Melville. Christopher Benfey admits he dreaded reading this latest, but he comes away mostly impressed. . . . John Self considers a new edition of a 1950s novel in which UK and U.S. astronomers simultaneously discover the “existence of a black cloud in the outer regions of the solar system” that is moving toward Earth. “Gentlemanly panic, tempered by scientific curiosity, ensues.”

Dwight Garner says that Avi Steinberg’s Running the Books, which recounts the author’s time as a prison librarian in Boston, “gets off to an obnoxious start,” reading mostly like a “hopped-up” gimmick. But according to Garner, the gimmick deepens into something much more: “Mr. Steinberg’s sentences start to pop out at you, at first because they’re funny and then because they’re acidly funny. The book slows down. It blossoms. Mr. Steinberg proves to be a keen observer, and a morally serious one. His memoir is wriggling and alive — as involving, and as layered, as a good coming-of-age novel.” . . . Maile Meloy makes Thomas McGuane’s latest sound like a lot of fun, even if it’s a bit sloppy in squaring all the facts of its fictional world: “As with McGuane’s earlier novels, the rambling plot is sustained because the individual episodes are a pleasure, often farcical and always acutely observed, and because the hero is sympathetic in his dissociated journey.” . . . Patrick Marnham reviews Pedigree, the “lengthy but little-read autobiographical novel” by Georges Simenon, “a Dickensian portrait, with poverty, crime, lunacy, wealth, corruption, and mockery, but a complete absence of Dickensian sentimentality.” . . . Jay Parini has written novels about Tolstoy, Walter Benjamin, and now, Herman Melville. Christopher Benfey admits he dreaded reading this latest, but he comes away mostly impressed. . . . John Self considers a new edition of a 1950s novel in which UK and U.S. astronomers simultaneously discover the “existence of a black cloud in the outer regions of the solar system” that is moving toward Earth. “Gentlemanly panic, tempered by scientific curiosity, ensues.”

Friday, October 22nd, 2010

Charles Yu, author of the recently published novel How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe

Charles Yu, author of the recently published novel How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe , lists 10 of his favorite books about time travel. He starts with Slaughterhouse-Five, always a good choice. (“Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.”)

, lists 10 of his favorite books about time travel. He starts with Slaughterhouse-Five, always a good choice. (“Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.”)

The rest of his list is worth reading, and then there are several compelling additions from people in the comments underneath the piece. One of them is The Technicolor Time Machine by Harry Harrison. Published in 1957, it sounds very Terry Gilliam. Wikipedia sums up its plot:

The narrative revolves around the efforts of a mediocre film director to save his job, his livelihood and just incidentally the studio he works for. To do this, he enlists a mad scientist, the crooked studio owner, a jazz tuba player, a cowboy, two fabulously stupid movie stars, and a real live ocean-crossing Viking. He ends up making history, but in a way he never dreamed of.

A few more that caught my eye: Behold the Man by Michael Moorcock, a short book — controversial, I’m sure — in which someone from 1970 travels back in time to find Jesus and ends up assuming the role of the savior when the facts don’t match what he was expecting to find. (The book has also had, as you can imagine, its share of amazingly ’70s-ish covers: here, here and here, for starters.) Replay

by Michael Moorcock, a short book — controversial, I’m sure — in which someone from 1970 travels back in time to find Jesus and ends up assuming the role of the savior when the facts don’t match what he was expecting to find. (The book has also had, as you can imagine, its share of amazingly ’70s-ish covers: here, here and here, for starters.) Replay by Ken Grimwood, in which a man keeps going back in time with his memories of the future intact, a la Groundhog Day (which the novel predates).

by Ken Grimwood, in which a man keeps going back in time with his memories of the future intact, a la Groundhog Day (which the novel predates).

And Sputnik Caledonia by Andrew Crumey, a story of time travel and alternative history. John Self reviewed the book here, and interviewed Crumey here.

by Andrew Crumey, a story of time travel and alternative history. John Self reviewed the book here, and interviewed Crumey here.

Thursday, October 21st, 2010

Thomas McGuane’s new novel, Driving on the Rim

Thomas McGuane’s new novel, Driving on the Rim , is just out, and Charles McGrath profiles him for the New York Times: “There’s a view of Montana writing that seems stage-managed by the Chamber of Commerce — it’s all about writers like A. B. Guthrie and Ivan Doig. It used to bother me that nobody had a scene where somebody was delivering a pizza.” . . . Richard Ford’s next novel is going to be set in Canada. And called that, too. . . . Scott Pack recently wrote that, in honor of his 40th birthday, he’s going to blog about “the 40 books that have most moved, delighted, astounded, impressed and entertained me since I emerged screaming in the maternity ward of Rochford Hospital in 1970.” The first two have inspired strong posts: a memoir by Frank Muir and a sci-fi novel Pack read as a boy. . . . By and large, I think book trailers are an enormous waste of time. But I like John Lanchester, and I like this book trailer. Do I like it as a book trailer? Well, the philosophy of all this deserves a separate post sometime. . . . Greil Marcus and Sean Wilentz, each with a book about Bob Dylan recently published, discuss Mr. Zimmerman with James Mustich. . . . If you’re in New York tonight, there’s a Bookslut event in Brooklyn that sounds like fun. . . . Alexander Chee writes about teaching the graphic novel, and which ones he taught: “[I]n my experience over the years, there are few things more politically dangerous within an English Department than teaching something popular with students.” . . . The Millions links to a sign of the times in a Barnes & Noble store.

, is just out, and Charles McGrath profiles him for the New York Times: “There’s a view of Montana writing that seems stage-managed by the Chamber of Commerce — it’s all about writers like A. B. Guthrie and Ivan Doig. It used to bother me that nobody had a scene where somebody was delivering a pizza.” . . . Richard Ford’s next novel is going to be set in Canada. And called that, too. . . . Scott Pack recently wrote that, in honor of his 40th birthday, he’s going to blog about “the 40 books that have most moved, delighted, astounded, impressed and entertained me since I emerged screaming in the maternity ward of Rochford Hospital in 1970.” The first two have inspired strong posts: a memoir by Frank Muir and a sci-fi novel Pack read as a boy. . . . By and large, I think book trailers are an enormous waste of time. But I like John Lanchester, and I like this book trailer. Do I like it as a book trailer? Well, the philosophy of all this deserves a separate post sometime. . . . Greil Marcus and Sean Wilentz, each with a book about Bob Dylan recently published, discuss Mr. Zimmerman with James Mustich. . . . If you’re in New York tonight, there’s a Bookslut event in Brooklyn that sounds like fun. . . . Alexander Chee writes about teaching the graphic novel, and which ones he taught: “[I]n my experience over the years, there are few things more politically dangerous within an English Department than teaching something popular with students.” . . . The Millions links to a sign of the times in a Barnes & Noble store.

Thursday, October 14th, 2010

In the wake of the National Book Awards announcement yesterday, Sam Anderson says, “I still believe that Freedom is a great novel; I still want to eat some of its sentences with tiny little corn holders.” But he doesn’t mind that it was left off the list of nominees.

In the wake of the National Book Awards announcement yesterday, Sam Anderson says, “I still believe that Freedom is a great novel; I still want to eat some of its sentences with tiny little corn holders.” But he doesn’t mind that it was left off the list of nominees.

He also links to an addictive read: a 2008 piece in the Guardian, in which one Booker Prize judge for every year since 1969 discusses the voting process for the year they served. It’s full of gossip, candid enthusiasms and regrets, and thoughts about the value (or lack thereof) of literary prizes. It’s also a good way to trip over some recommendations you might not otherwise find.

Beryl Bainbridge, who judged in 1977, wrote:

All I can remember of the final meeting is that I got terribly tired, I literally sank lower and lower under the table. Brendan Gill, who I thought was American, went towards the balcony saying he was going to throw himself off, he was so fed up. Philip Larkin was completely silent most of the time. Nobody dared say a word to him and he never said a word back.

Paul Bailey (1982) wrote, “There are many things I regret doing, and being a judge for the Booker prize is one of them.” Noting a later snub that other judges did as well, but with more venom, Bailey said, “A wonderful book such as Penelope Fitzgerald’s The Blue Flower was completely ignored, and I hope the judges for 1995 are blushing now to be reminded of their grotesque oversight.”

Jason Cowley (1997) echoed the feelings of another judge, Ruth Rendell, when he said, “I often think that I’ve never quite recovered from my experience of being a judge. I began the year as an enthusiastic and engaged reader and reviewer of contemporary fiction, and ended it much more interested in non-fiction and narrative journalism.”

And Hilary Mantel, who served in 1990, said, “I’m glad I was a Booker judge relatively early in my career. It stopped me thinking that literary prizes are about literary value. Even the most correct jury goes in for horsetrading and gamesmanship, and what emerges is a compromise.” Mantel won the prize last year for Wolf Hall. Given the raft of other awards it’s won, I’m not sure that particular Booker was a compromise.

Mantel, and more than one other judge, believes the all-time best winner of the Booker is The Siege of Krishnapur by J. G. Farrell, making it the second novel of Farrell’s I’m now eager to read. Better get on that.

by J. G. Farrell, making it the second novel of Farrell’s I’m now eager to read. Better get on that.

Fay Weldon’s account of the 1983 voting is worth reading in full. I’ll leave you to it.

Wednesday, October 13th, 2010

The National Book Award finalists have been announced. In fiction, the lead story will probably be the absence of Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom. The other news is the presence of two small-press titles: I Hotel

The National Book Award finalists have been announced. In fiction, the lead story will probably be the absence of Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom. The other news is the presence of two small-press titles: I Hotel by Karen Tei Yamashita and Lord of Misrule

by Karen Tei Yamashita and Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon. Of the two, Lord of Misrule seems particularly surprising — Gordon’s novel was published by McPherson & Company, and it’s set at a run-down horse track in West Virginia. Sounds like something I might really enjoy.

by Jaimy Gordon. Of the two, Lord of Misrule seems particularly surprising — Gordon’s novel was published by McPherson & Company, and it’s set at a run-down horse track in West Virginia. Sounds like something I might really enjoy.

I Hotel was published by Coffee House Press. Publishers Weekly said that Yamashita “strings together a stunningly complete vision of San Francisco’s Asian American community in the late 1960s and early ’70s, using the titular inn as a meeting point for ten loosely-connected novellas, each covering a single year.” That PW review concluded with this: “with varied commingling of voices and formats (stream-of-consciousness, slangy first person, quotes, dossiers, academic papers, even written-out choreography), the narrative reads like a collection of primary sources. Though it isn’t for everyone, this powerful, deeply felt, and impeccably researched fiction is irresistibly evocative and overwhelming in every sense.”

The nominees for fiction and nonfiction are below. For other categories, visit the NBA site (which appears to be down at the moment).

Fiction:

Parrot and Olivier in America by Peter Carey

Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon

Great House by Nicole Krauss

So Much for That by Lionel Shriver

I Hotel by Karen Tei Yamashita

Nonfiction:

Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea by Barbara Demick

Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima, 9-11, Iraq by John W. Dower

Just Kids by Patti Smith

Secret Historian: The Life and Times of Samuel Stewar by Justin Spring

Every Man in This Village Is a Liar: An Education in War by Megan K. Stack

Wednesday, October 13th, 2010

Lane Smith writes a charming (and charmingly illustrated) post about writing his new children’s book, It’s a Book

Lane Smith writes a charming (and charmingly illustrated) post about writing his new children’s book, It’s a Book , which teaches children about that non-digital oddity. Sadly, Smith scrapped the hilarious character at left because, understandably, he didn’t want anyone to think he was making fun of a goofy child. The post includes thoughts about Buster Keaton and the spatial concerns of comedy, porkpie hats, and a mini-history of the jackass as a character in children’s literature. Read it. . . . Speaking of the young, Jill Lepore, reliably entertaining and informative, writes about a new round of books explaining sex to children and the history of the genre. . . . Howard Jacobson has won the Booker Prize for his novel The Finkler Question

, which teaches children about that non-digital oddity. Sadly, Smith scrapped the hilarious character at left because, understandably, he didn’t want anyone to think he was making fun of a goofy child. The post includes thoughts about Buster Keaton and the spatial concerns of comedy, porkpie hats, and a mini-history of the jackass as a character in children’s literature. Read it. . . . Speaking of the young, Jill Lepore, reliably entertaining and informative, writes about a new round of books explaining sex to children and the history of the genre. . . . Howard Jacobson has won the Booker Prize for his novel The Finkler Question , which just went on sale in the U.S. Claire Armitstead says Jacobson’s win is overdue, but that, “many of his fans [will suspect] that, like Margaret Atwood and Ian McEwan before him, he didn’t break the jinx with his best novel.” The Guardian profiled Jacobson in August, and the same paper recently ran an essay by him about the history of, and importance of, humor in novels. . . . Andrew Seal shares a list of books that Theodore Dreiser kept on his shelves under the group title “Library of American Realism.” . . . Levi Stahl, fan of scary stories, welcomed in “October Country” last week, and it seems that this month at his terrific blog will be dedicated to literary frights. . . . Rohan Maitzen admires Elizabeth Hardwick’s confidence, and shares several excerpts from her work.

, which just went on sale in the U.S. Claire Armitstead says Jacobson’s win is overdue, but that, “many of his fans [will suspect] that, like Margaret Atwood and Ian McEwan before him, he didn’t break the jinx with his best novel.” The Guardian profiled Jacobson in August, and the same paper recently ran an essay by him about the history of, and importance of, humor in novels. . . . Andrew Seal shares a list of books that Theodore Dreiser kept on his shelves under the group title “Library of American Realism.” . . . Levi Stahl, fan of scary stories, welcomed in “October Country” last week, and it seems that this month at his terrific blog will be dedicated to literary frights. . . . Rohan Maitzen admires Elizabeth Hardwick’s confidence, and shares several excerpts from her work.

Tuesday, October 12th, 2010

On Wednesday, Nov. 10, The Second Pass will venture out into the world for its first event: a reading and party at the terrific Melville House Bookstore in Brooklyn. If you’re in the New York area, I hope you can join us.

The reading portion of the night will involve brief readings from works in progress by four Second Pass contributors:

Carlene Bauer

The author of the memoir Not That Kind of Girl , Carlene has written for Salon, Slate, n+1, the New York Times Magazine, and several other publications.

, Carlene has written for Salon, Slate, n+1, the New York Times Magazine, and several other publications.

Will Blythe

The author of To Hate Like This Is to Be Happy Forever , a personal account of the storied North Carolina-Duke basketball rivalry, Will is a widely published critic and journalist whose work regularly appears in the New York Times Book Review, among many other places.

, a personal account of the storied North Carolina-Duke basketball rivalry, Will is a widely published critic and journalist whose work regularly appears in the New York Times Book Review, among many other places.

Maud Newton

For more than eight years, Maud has maintained her very popular, eponymous literary blog. She is also a widely published critic and essayist, and the winner of the 2009 Narrative Prize for an excerpt from her novel-in-progress.

Jason Zinoman

A theater critic for the New York Times, Jason is at work on a book about horror movies in the 1970s and the birth of the modern genre. His work has appeared, among other places, in Slate and Vanity Fair, for which he wrote about horror movies in 2008.