If you’ve reached this point and still need holiday gifts (or if you’re looking to redeem an Amazon gift certificate someone gave you), below are some belated ideas for the readers in your life. Some of them are related to things that happened on The Second Pass this year, some are not.

If you’ve reached this point and still need holiday gifts (or if you’re looking to redeem an Amazon gift certificate someone gave you), below are some belated ideas for the readers in your life. Some of them are related to things that happened on The Second Pass this year, some are not.

If you click through to Amazon from any of the links below, whatever you end up buying there will benefit The Second Pass in some small way. Since I don’t have pledge drives (yet), this is a great way for you to support what goes on around here if you enjoy it. And if you’re a high roller who happens to be reading, and you’d like to order that someone special The Penguin Classics Library Complete Collection for a cool $13,000 — well, $13,413.30, but who’s counting? — I, for one, will not stand in your way. Now, on to a few more realistic options:

for a cool $13,000 — well, $13,413.30, but who’s counting? — I, for one, will not stand in your way. Now, on to a few more realistic options:

The Paris Review Interviews, Vols. 1-4 would always be a great gift, but perhaps especially now that all of the venerable journal’s interviews are available online. What better way to express love for physical books than to buy them anyway?

would always be a great gift, but perhaps especially now that all of the venerable journal’s interviews are available online. What better way to express love for physical books than to buy them anyway?

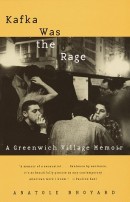

For New Yorkers or fans of reading about New York, just a few suggestions from the countless possibilities: The Cambridge Companion to the Literature of New York is a series of incisive essays about Melville, Whitman, “the early literature of New York’s moneyed class,” the Villages (Greenwich and East), and “writing Brooklyn,” among other subjects. Up in the Old Hotel

is a series of incisive essays about Melville, Whitman, “the early literature of New York’s moneyed class,” the Villages (Greenwich and East), and “writing Brooklyn,” among other subjects. Up in the Old Hotel is a collection of the great Joseph Mitchell’s tales (some surely taller than others) of the city and its characters from the 1930s to the early 1960s. The City’s End: Two Centuries of Fantasies, Fears, and Premonitions of New York’s Destruction

is a collection of the great Joseph Mitchell’s tales (some surely taller than others) of the city and its characters from the 1930s to the early 1960s. The City’s End: Two Centuries of Fantasies, Fears, and Premonitions of New York’s Destruction by Max Page is an illustrated look at just what the subtitle promises, from attacks by giant babies to great-flood scenes from 1951 and beyond. Or the less apocalyptic Celluloid Skyline: New York and the Movies

by Max Page is an illustrated look at just what the subtitle promises, from attacks by giant babies to great-flood scenes from 1951 and beyond. Or the less apocalyptic Celluloid Skyline: New York and the Movies by James Sanders, which tracks the history of the city on film.

by James Sanders, which tracks the history of the city on film.

Speaking of movies, the 2011 edition of the Time Out Film Guide is available. For my money, it’s the best of the doorstop movie guides. I’m tempted to buy it every year, which would be wasteful; so I tend to buy it every other year, which is just pretty wasteful.

is available. For my money, it’s the best of the doorstop movie guides. I’m tempted to buy it every year, which would be wasteful; so I tend to buy it every other year, which is just pretty wasteful.

If you enjoyed William James Week, which happened here over the summer, and you’re looking for a primer, there’s a Library of America collection that features a few of his best-known works: The Varieties of Religious Experience, Pragmatism, A Pluralistic Universe, and more. I’m also, as I’ve said more than once before, a big fan of Robert D. Richardson’s biography

that features a few of his best-known works: The Varieties of Religious Experience, Pragmatism, A Pluralistic Universe, and more. I’m also, as I’ve said more than once before, a big fan of Robert D. Richardson’s biography of James.

of James.

Or perhaps, going back to 2009, you liked the week highlighting the correspondence of authors. The Habit of Being , a collection of Flannery O’Connor’s letters, is a good place to start. I think they’re the best things she wrote. The letters of E. B. White

, a collection of Flannery O’Connor’s letters, is a good place to start. I think they’re the best things she wrote. The letters of E. B. White are terrific. And though out of print, it’s worth tracking down a used copy of the letters of Raymond Chandler

are terrific. And though out of print, it’s worth tracking down a used copy of the letters of Raymond Chandler edited by Frank MacShane, maybe especially for writers or aspiring writers. Chandler is often hilariously dyspeptic about his own work, the publishing industry, and the work of other authors.

edited by Frank MacShane, maybe especially for writers or aspiring writers. Chandler is often hilariously dyspeptic about his own work, the publishing industry, and the work of other authors.

For the sports geek in your life, especially if that geek grew up in the 1970s and 1980s, there’s Cardboard Gods , Josh Wilker’s memoir, told through a close reading of his baseball card collection. It includes great full-color reproductions of all the cards. (Some of the most fun I had this year was discussing the book with my friend Jon Fasman.)

, Josh Wilker’s memoir, told through a close reading of his baseball card collection. It includes great full-color reproductions of all the cards. (Some of the most fun I had this year was discussing the book with my friend Jon Fasman.)

If you know a fan of short stories, they should already own the work of William Trevor. If they don’t, consider the first volume of his collected stories or the (recently published) second volume

of his collected stories or the (recently published) second volume . Those are both hefty volumes. For a slimmer collection of stories that still packs a punch, there’s my favorite book of 2009, Lydia Peelle’s Reasons for and Advantages of Breathing

. Those are both hefty volumes. For a slimmer collection of stories that still packs a punch, there’s my favorite book of 2009, Lydia Peelle’s Reasons for and Advantages of Breathing . (My review of that one is here.)

. (My review of that one is here.)

I wasn’t crazy about a lot that was published in 2010, but I’m a fan of The Lonely Polygamist by Brady Udall (which I reviewed here). This is for the Richard Russo or John Irving fan in your life, not the Thomas Bernhard or Michel Houellebecq junkie. (Though I like Bernhard and Udall, so I guess I should shut up.) Udall’s first novel, The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint

by Brady Udall (which I reviewed here). This is for the Richard Russo or John Irving fan in your life, not the Thomas Bernhard or Michel Houellebecq junkie. (Though I like Bernhard and Udall, so I guess I should shut up.) Udall’s first novel, The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint , is also a treat.

, is also a treat.

Like I said, these are just a few belated thoughts. I believe Amazon is offering free two-day shipping until early Wednesday night, so get cracking. And this is not a holiday post to close out the year around here. More to come this week, and maybe even a pop-in or two next week…

The Second Pass turns two years old today. I want to thank everyone — as always — for visiting, reading, passing pieces along to friends, commenting, following the site

The Second Pass turns two years old today. I want to thank everyone — as always — for visiting, reading, passing pieces along to friends, commenting, following the site  Adam Mansbach

Adam Mansbach  Luc Sante (on John Gall’s blog)

Luc Sante (on John Gall’s blog)  Even readers who appreciated the brainiest subtleties of David Foster Wallace’s work might find his college thesis about the philosophy of fatalism rough sledding. Here’s a brief excerpt:

Even readers who appreciated the brainiest subtleties of David Foster Wallace’s work might find his college thesis about the philosophy of fatalism rough sledding. Here’s a brief excerpt: Michael Dirda reaches early and often for the top-shelf bag of references

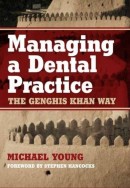

Michael Dirda reaches early and often for the top-shelf bag of references  The short list of finalists for the Diagram Prize for the Oddest Book Title of 2010

The short list of finalists for the Diagram Prize for the Oddest Book Title of 2010  OK, this is getting serious. The Tournament of Books (for which I’m lucky enough to be a judge this year)

OK, this is getting serious. The Tournament of Books (for which I’m lucky enough to be a judge this year)  FSG’s Work in Progress site is featuring an excerpt from Geoff Dyer’s forthcoming book of essays and reviews. It concerns

FSG’s Work in Progress site is featuring an excerpt from Geoff Dyer’s forthcoming book of essays and reviews. It concerns  Dwight Garner reviews

Dwight Garner reviews  Reynolds Price

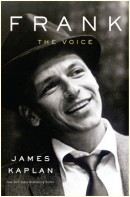

Reynolds Price  Geoffrey O’Brien reviews James Kaplan’s biography of Frank Sinatra, which covers

Geoffrey O’Brien reviews James Kaplan’s biography of Frank Sinatra, which covers  Every March, the online magazine The Morning News hosts the knock-down, drag-out Tournament of Books, wherein 16 works of fiction compete to be called the year’s best. Then, at the end, they play

Every March, the online magazine The Morning News hosts the knock-down, drag-out Tournament of Books, wherein 16 works of fiction compete to be called the year’s best. Then, at the end, they play  For the last three years, I’ve been lucky enough to spend New Year’s week at a house in Massachusetts with a group of eight to 10 friends, Big Chill-style (minus the funeral and most of the collective self-loathing). One highlight of each visit is a trip to the local library, which is always giving away books that time of year.

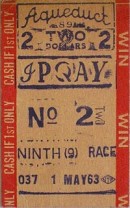

For the last three years, I’ve been lucky enough to spend New Year’s week at a house in Massachusetts with a group of eight to 10 friends, Big Chill-style (minus the funeral and most of the collective self-loathing). One highlight of each visit is a trip to the local library, which is always giving away books that time of year. I also picked up The Existential Imagination by Frederick R. Karl and Leo Hamalian. I was thinking about bringing it home for a couple reasons: first, because I’ve found a few other old mass-market paperbacks about existentialism in such places, and it’s a nice mini-collection to have; and secondly, because it was free. The deal was sealed when I noticed what a prior reader had used to mark their place: a beautiful ticket from a horse race at Aqueduct in 1963. As a fan of horse racing, this was hard to resist. I suppose I could have just lifted the ticket and left the book, but as a fan of books, that was unlikely.

I also picked up The Existential Imagination by Frederick R. Karl and Leo Hamalian. I was thinking about bringing it home for a couple reasons: first, because I’ve found a few other old mass-market paperbacks about existentialism in such places, and it’s a nice mini-collection to have; and secondly, because it was free. The deal was sealed when I noticed what a prior reader had used to mark their place: a beautiful ticket from a horse race at Aqueduct in 1963. As a fan of horse racing, this was hard to resist. I suppose I could have just lifted the ticket and left the book, but as a fan of books, that was unlikely. Edmund White chooses

Edmund White chooses  Timothy Noah at Slate recently wrote

Timothy Noah at Slate recently wrote  Richard Williams

Richard Williams  This

This  James Morrison (aka Caustic Cover Critic) has begun designing and publishing

James Morrison (aka Caustic Cover Critic) has begun designing and publishing  The Millions has

The Millions has  Over the holidays, I found two fascinating pieces about women who wrote in the first half of the 20th century. The

Over the holidays, I found two fascinating pieces about women who wrote in the first half of the 20th century. The  Rather than round up a few of the more traditional lists of the year’s best and worst, I thought I would point you to some bloggers who wrote more broadly about their year in reading. Below are some links. Two books that I’ve seen appearing again and again on lists are

Rather than round up a few of the more traditional lists of the year’s best and worst, I thought I would point you to some bloggers who wrote more broadly about their year in reading. Below are some links. Two books that I’ve seen appearing again and again on lists are  If you’ve reached this point and still need holiday gifts (or if you’re looking to redeem an Amazon gift certificate someone gave you), below are some belated ideas for the readers in your life. Some of them are related to things that happened on The Second Pass this year, some are not.

If you’ve reached this point and still need holiday gifts (or if you’re looking to redeem an Amazon gift certificate someone gave you), below are some belated ideas for the readers in your life. Some of them are related to things that happened on The Second Pass this year, some are not. Here’s

Here’s