Reviewed:

Reviewed:

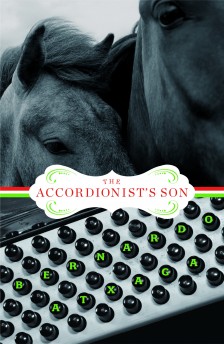

The Accordionist’s Son by Bernardo Atxaga

Graywolf Press, 400 pp., $25.00

The Accordionist’s Son is a serious book that does not feel heavy. The product of two different fictional narrators, each writing for disparate purposes, and featuring multiple jumps through time and form, it is nevertheless a straightforward and altogether unconfusing read. Through the use of certain repeated images — butterflies and eyes chief among them — Bernardo Atxaga is able to generate a resilient and complex system of internal correspondences that lend structure to the seemingly random flow of an unfinished memoir. The novel never feels contrived, never strident or overwrought.

The story begins with the funeral of its title character. David Imaz, a Spanish Basque who has relocated to Northern California in adulthood, leaves behind a wife, two young daughters, and a memoir — “a letter-sized book of about two hundred beautiful bound pages” — written not in Spanish or in English, but Basque, a language “spoken by less than a million people.” Since neither David’s wife (a Canadian) nor children are among those million, a childhood friend who has come to the funeral offers to translate the pages — sort of. The friend, Joseba, also intends to edit and supplement what David has left behind. “I [want] to write a book based on what David [wrote],” he explains. “Not like someone pulling down a house and building a new one in its place, but in the spirit of someone finding a tree, on which some long-vanished shepherd had left a carving, and deciding to redraw the lines so as to bring out and enhance the drawing and the figures.”

This edited memoir (also called The Accordionist’s Son) comprises the majority of the novel’s remaining pages. It begins with the protagonist’s acquisition of what his mother calls a set of “second eyes” — a pair “alongside those we have in our head . . . that mostly show us only troubling images.” For David, the images are of village men murdered by fascist soldiers during the Spanish Civil War. Nearby stand those villagers who collaborated with the fascists, betraying their countrymen to further their own aims. Among these betrayers, laughing, is David’s father, Angel.

Incited by what this vision causes him to suspect, David begins to investigate his father’s past. The more he learns, the more he questions, and slowly he becomes alienated from his family, and his village. He moves away from his family home, forsaking the accordion for Basque poetry and avoiding not only his father but also other villagers whom he believes collaborated. When he refuses to play his accordion at a ceremony to commemorate Franco’s soldiers, he is forced to go underground — to hide out in the exact same room used during the war to shelter men from the fascists. Soon after, he departs the village for good, joining with a group of Basque separatists and becoming peripherally involved in a series of semi-terrorist acts against the Spanish government.

Only in his late thirties, ensconced in the domestic tranquility he finds in America, does David begin to accept his family history. As he writes, “If I hadn’t had those suspicions about Angel, I never would have struggled. If I hadn’t struggled I never would have become strong. If I hadn’t become strong, I never would have been able to move on.”

Movement is a crucial term for understanding this novel; “moving on” summarizes not only the story, but its central narrative tactic. The story zooms past, jumping through time and place, from speaker to speaker, from truth to fiction. It contains shepherds, priests, intellectuals, and everyone in between. (Raquel Welch even makes a cameo.) The locales vary almost as widely, and the book’s action unfolds over five decades. What it gains in breadth and in speed, however, it loses in depth. Here, for example, is a description of a dead body after it’s pulled from a river:

Lubis’s body was still lying on the pebbles. A man lit up his face with a flashlight. “That was some blow! His eye’s almost out of his socket!” said someone.

In the knot of people that had formed around the corpse, a discussion arose as to whether the real cause of death had been the blow or the fact of remaining under the water unconscious. The man with the flashlight kept moving it about, and the ring of light flicked over the dead face. Sometimes it seemed that it wasn’t the light that was moving, but a part of the face, the lips or the eyes, and that we were all wrong, Lubis wasn’t really dead. However, the torch finally stopped at the battered eye, and the triumph of death became clear.

You’d never guess from the tone, but the body here belongs to one of the narrator’s closest friends. His death was not an accident, but a revenge killing carried out by fascist soldiers who mistake him for a separatist agitator. It is a moment of significant dramatic importance, and yet it barely registers. Its outlines, like the pastoral carvings that Joseba has referenced earlier, have grown vague, effaced by time and memory. What we are reading, we sense, no longer matters to the speaker — he has, in every sense, moved on.

Unfortunately, this same sensation comes frequently to the reader of The Accordionist’s Son, much of which speeds by in a vague and impalpable blur. Reading this book is like undertaking a tour of a vibrant far-flung locale from within the confines of a luxuriously appointed car. There are no bumps or jolts; the thick windows keep away the bugs; and the temperature never strays beyond a comfortable sixty-eight. It’s hardly a journey you’d regret — but neither is it one you’re likely to remember.

Tim Lake is a writer in Los Angeles.

Books mentioned in this review: