Reviewed:

Danse Macabre by Stephen King

Berkley, 464 pp., $7.99

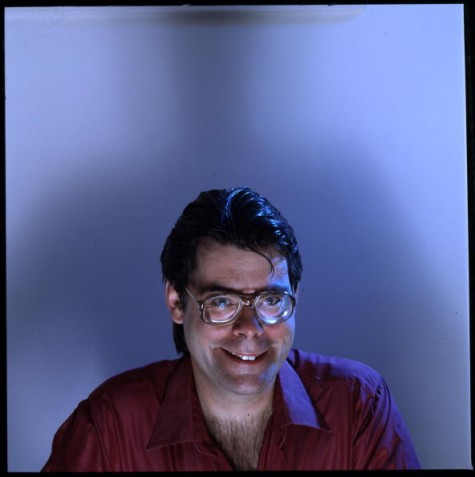

“There are apparently two books in every American household – one of them is the Bible and the other one is probably by Stephen King,” Clive Barker once wrote with what sounds like more than a hint of jealousy. In the world of modern horror fiction, Barker, the English novelist and director of Hellraiser, is certainly a player, but King, more than anyone else, established the rules. Having sold more than 300 million books – and generated countless millions of box office revenue, starting with Carrie in 1976 – his nightmares have become ours.

That’s why it’s strange that his one definitive statement about the genre, Danse Macabre, written at the height of his powers in 1981, remains so obscure. This pleasingly opinionated history of horror is a treasure trove of insights that include philosophical musings, deeply considered thoughts on both classics and lost gems, and a probing discussion of the sadistic and masochistic impulses of the horror fan. It’s the master imparting his secrets, and in the process, making an impassioned argument for the virtue of trembling in the dark.

King’s book is the result of a lifetime of immersion in ghosts, vampires and other bogeymen, and part of the reason it remains relatively unknown might be that it occasionally adopts the esoteric tone of the Star Trek fan who refuses to discuss the show with anyone who doesn’t speak Klingon. When King mentions the plot of “The Monkey’s Paw” or drops the name of Forrest Ackerman, he expects you to know what he’s talking about. In return, he promises not to pull punches – “If you’ve seen one film by Wes Craven, for instance, it’s safe, I think, to skip the others,” goes a typically blunt assessment – or flatter you with dry intellectual justifications. “Analysis is a wonderful tool in matters of intellectual appreciation,” he writes, “but if I start writing about the cultural ethos of Roger Corman or the social implications of The Day Mars Invaded the Earth, you have my cheerful permission to pop this book into a mailer, return it to the publisher and demand your money back.”

King is as wary of pop psychology as ivory tower theories, but since he looms so large over the genre, he wisely – if grudgingly – traces the origin of his interest in the dark side. It all began, appropriately, in a dark attic with creaky floorboards above his uncle’s garage. Rifling through a box of his father’s belongings – Doug King left home when his son was two years old, never to return – he found a book called The Lurking Fear and Other Stories by H. P. Lovecraft. What struck him first was the cover – a creepy picture of red eyes peering out from beneath a tombstone. He took the book downstairs carefully, knowing that his aunt would not approve, and started reading. At this point in the story, it’s best to imagine a wild-haired doctor shouting, “It’s alive!”

In Lovecraft, that wonderful poet of purple prose and the artistic father of countless genre writers, including Robert Bloch (Psycho) and Dan O’Bannon (the screenplay for Alien), King found a seriousness of purpose and fevered literary style that had nothing in common with the silly monsters at his local movie theater in remote Maine. “[Lovecraft] wasn’t simply kidding around or trying to pick up a few extra bucks,” King wrote in a chapter called “An Annoying Autobiographical Pause.” “He meant it.”

So does King. Whatever you want to say about him as a writer – at best, his prose is workmanlike; at worst, it lurks forward, with the repeated movements and quick wit of a zombie – King believes deeply in what he does. He recently caused a fuss by desecrating the good name of Stephenie Meyer, author of Twilight and hero of little girls everywhere. “She can’t write worth a darn,” King said, sounding like the cranky old veteran that he is. But that’s not jealousy. As Danse Macabre reveals, King has very rigid standards, even if he often fails to meet them himself. Like any horror fan, he has a taste for trash – “The Amityville Horror is pretty pedestrian. So’s beer, but you can get drunk on it.” – but get him going about William Castle and he can sound like the Susan Sontag of the horror set.

The book wanders terribly – any good editor could have easily trimmed its more than 400 pages by a third in a few hours – but there’s something decidedly pleasurable about King’s tangents. Some of his most interesting and unorthodox arguments are found in throwaway lines. In a footnote, he makes a persuasive case that Alien, a film with one of the strongest scream queens of all time, is unforgivably sexist. And there’s nothing King likes more than pausing to champion the overlooked artist. If his novels are hard to put down, Danse Macabre insists you do just that, in order to read and watch others. His raves about obscure radio writer Arch Oboler and Boris Karloff’s short-lived television series Thriller (far superior to The Twilight Zone, according to him) will send you scrambling to the Internet. And his close reading of the chilling first paragraph in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House will restore your faith in the power of that old chestnut: the haunted house story.

For a writer who has received more than his share of damning notices, King truly thinks like a critic, sometimes to a fault. For one thing, he loves classifications, breaking his subject down into four groups (radio, film, television, fiction), then three (terror, horror and the gross-out), then two (inner and outer horror). Some of these categories can seem arbitrary, but others are useful in making sense of an ever-growing genre. He repeatedly relies on one important distinction, established early in the book, between the disturbing images on the surface in horror and the pleasures found in another, deeper place, which he describes as “the place where you live at your most primitive level.” This psychic soft spot – the “phobic pressure point,” as he puts it – is where horror becomes art.

The modern horror story can, with few exceptions, be traced back to the Holy Trinity of fright (Dracula, Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) which popularized or created the most enduring monsters – the vampire, what King calls “the thing with no name” (which includes everything from the monsters in Alien to The Thing), and the werewolf. Along with the ghost, which has a completely different and longer literary lineage, these are the building blocks for a century of scares – and Danse Macabre begins by explaining their appeal.

“Mary Shelley – let us bite the bullet – is not a particularly strong writer of emotional prose,” King writes, before explaining how this teenage girl came up with what may be the most frequently revived story in the history of film (the first Frankenstein adaptation, a short from 1910, was rumored to have been produced by Thomas Edison). He argues that her crucial accomplishment was complicating the villain. By splitting the audience into two camps – the ones that hated the reanimated creature and those who hated the mob hunting him down – Shelley set the standard for the sympathetic monster and “insured [the novel’s] long attractiveness to the movies.” Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a completely different beast. As many other critics have, King locates its main significance in sexual frankness and brutality. “Sex makes adolescent boys feel many things, but one of them, quite frankly, is scared,” he writes in a line that explains almost everything about the history of horror.

King saw something else unique about Stoker’s vision. In perhaps his most valuable distinction, he considers inside horror and outside horror. Most high-quality work is inside stuff, featuring villains committing motivated acts of free will: a scientist overreaching, an alien exploring Earth, cannibals eating. Outside horror simplifies character while expanding the reach of the evil, projecting an unexplainable, enveloping something that is larger and more awesomely powerful than one person’s bad choices. Lovecraft was the master of this technique, but you can also see it in the almost abstract characterization of the serial killer in John Carpenter’s Halloween. Who was that masked man, Michael Myers? Jamie Lee Curtis’ character replied trembling: “It was the bogeyman.”

Dracula, King argues, put a human face on this kind of outside horror. His evil was predestined and unexplained, and Stoker maintained the mystery of the character, to some degree, by keeping the Count offstage for almost the entire story. “Stoker creates his fearsome, immortal monster much the way a child can create the giant rabbit on the wall by waffling his fingers in front of a light,” King writes.

Like so many of the horror stories it examines, Danse Macabre works off a template: Lovecraft’s 1927 masterpiece Supernatural Horror in Literature, which was the first serious argument for what was then called The Fantastic as true literature. Even though he discusses the seminal stories of Lovecraft far too briefly, King pays homage to this book, instructing his readers to get a copy. At the same time, Danse Macabre is also something of a rebuke, the young master of horror rebelling against his surrogate father.

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear,” Lovecraft insistently begins his book, “and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” For Lovecraft, the essence of horror was a mysterious, almost religious sense of impending dread that is never fully revealed. You see those red eyes but not much else.

King explains the central problem of modern horror this way – the monster scratching at the creaky door is always scarier before you pull the knob, because no creature can be as grotesque as the one in your head. So what is an author to do? Lovecraft’s answer is never open the door, or only crack it open so that “just enough is suggested and just little enough is told.” (Lovecraft believed that horrific fantasy stories would always have a limited audience, since only the few sensitive souls with enough imagination could appreciate them.) King expresses sympathy for this position, but he just can’t help himself. “I recognize terror as the finest emotion and so I will try to terrorize the reader,” writes King. “But if I find that I cannot terrify, I will try to horrify, and if I find that I cannot horrify, I’ll go for the gross-out. I’m not proud.” It’s no accident that Lovecraft, whose stories have proved notoriously difficult to adapt to the screen, died penniless and King, to understate it, will not.

King’s vision of horror is rooted in the movies and comic books of his 1950s childhood, when the villains (arrogant scientists, cheating husbands) almost always received their comeuppance. And his most controversial and famous argument in Danse Macabre, one frequently quoted in articles about the genre, is that “horror is as conservative as a Republican in a three-piece suit.” King lays out the typical narrative this way: After presenting the establishment (say, the popular kids in high school) and then imagining the alternative (awkward virginal religious girl) in the darkest possible light (worst prom ever), the case is made for keeping the status quo. The societal outcast (or monster) intrudes on taboo territory, and only when it is repelled can order return. The author, King argues, is “an agent of the norm.”

It’s an interesting theory, albeit easy to disprove, since most directors of horror’s most recent golden age in the 1970s were counterculture figures. Their films were arguably attacks on liberal bugaboos such as racism (Night of the Living Dead), sexism (Rosemary’s Baby, The Stepford Wives) and war (Dead of Night). Moreover, can you say that the director of The Last House on the Left (one of those Craven films King too easily dismisses), a movie so brutally disturbing that the castration scene comes as a relief, was an “agent of the norm”? On this point, Lovecraft speaks more to the horror of today, since in his paranoid visions, terror seems like it’s everywhere and nowhere at once. Death is always just around the corner, or behind the door, waiting to strike. Lovecraft’s horror, far from leaving us in the comforting hands of the status quo, imagines a vast, unknowable universe, beyond politics, where we are victims of something ancient and ineradicable.

Since the publication of Danse Macabre, many academics have, building on King’s ideas, tried to explain the magnetic pull that images of chopped-up teenagers have on theatergoers. The best of these works have been The Philosophy of Horror, in which Noël Carroll argues provocatively that the genre’s appeal is not the monsters or the murders, but the fascination generated by the peculiar mechanics of the horror plot; and Carol Clover’s Men, Women, and Chain Saws, a godsend for progressive gore fans, which mounts a feminist defense of slasher films. These books take horror seriously as a cultural force, but one gets the sense that the authors spent years watching and thinking about these movies without actually, you know, liking them.

The most common excuse for the non-academic horror fan looking to justify his interest in watching women get stalked, sliced up, impaled, decapitated, ripped in half and drowned is that scary stories provide catharsis, allowing people to cope with the terror of the real world in a safe environment. If that idea helps you get through the night, great. But take a look at the quivering souls at your local multiplex and you won’t see many people grappling with a slasher film’s subtle relationship to the current economic crisis.

King himself doesn’t seem entirely sold on his theory about the conservatism of horror. He wonders if beneath the surface (or maybe it’s beneath what’s beneath the surface), horror isn’t just pure nihilism. “Suppose,” he speculates in one of those irresistible tangents, “it’s all a self-serving lie and that when the creator of horror is finally stripped all the way to his or her core of being we find not an agent of a norm but a friend – a capering, gleeful, red-eyed agent of chaos.”

There are those red eyes again. And that crisis of confidence is part of the fun of what have been called weird tales. After all, the best horror walks the line dividing exploitation and art, wobbling uneasily like a drunk having the time of his life, or a kid playing daredevil. Children understand horror far better than we think. We forget how scary it is to be young and dependent on the kindness of adults. Danse Macabre reminds us that getting frightened summons a certain nostalgic thrill, returning to the days when there were monsters in the closet, under the bed and lurking in the dark. No matter how old King gets, those red eyes will probably follow him forever.

Jason Zinoman writes about theater for the New York Times, and he is at work on a forthcoming book for The Penguin Press about the origins of the modern horror movie.

Books mentioned in this review:

Danse Macabre

The Supernatural Horror in Literature

The Lurking Fear and Other Stories

Frankenstein

Dracula

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde

The Haunting of Hill House

Psycho

Men, Women, and Chain Saws

The Philosophy of Horror