Reviewed:

Reviewed:

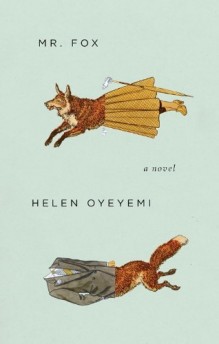

Mr. Fox by Helen Oyeyemi

Riverhead, 336 pp., $25.95

“You have to change. . . . You kill women. You’re a serial killer. Can you grasp that?” So says Mary Foxe, the fictional creation and erstwhile muse of St. John (S.J.) Fox, a 1930s-era author with a penchant for subjecting his female characters to grisly (he says “meaningful”) deaths and dismemberments. A quick survey: a bride saws off her limbs and bleeds to death at the altar; a housewife hangs herself over a ruined dinner; a husband beheads his wife, thinking he would “replace her head when he wished for her to speak.” Tired of being subjected to such fates herself, Mary Foxe — apparently unbound by the pages of the books in which she has existed — casually appears in S.J.’s study and challenges her progenitor to enter a fictional world of her own making, one where he just might find himself the victim for a change.

As those who are well-versed in European folkloric traditions will have guessed, Mr. Fox, the fourth novel by 26-year-old Helen Oyeyemi, takes its inspiration from the myriad fairy tales and traditional narratives about murderous men luring attractive young women to their deaths. Oyeyemi’s novel references Bluebeard and the famous French character based on the 15th century soldier/serial killer Gilles de Rais, and also draws from the Grimm Brothers’ tale “Fitcher’s Bird,” a Victorian ballad about a werefox named Reynardine, the German folk character of the Robber Bridegroom, and, of course, the English fairy tale “Mister Fox.”

The heroine of “Mister Fox” (which coined the refrain “Be bold, be bold, but not too bold”) is Lady Mary, who witnesses her dashing suitor, Mr. Fox, chopping off the hand of a young woman before dragging her to certain death in his castle’s “bloody chamber.” The stalwart Mary escapes with the young woman’s hand, and later reveals Mr. Fox as the villain he is by telling the “dream” she had of the young woman’s murder and furnishing the hand as evidence. Bluebeard mythology includes several tales in which the female characters safely escape in the end, but in the context of Oyeyemi’s novel, “Mister Fox” is all the more noteworthy because the heroine bests her would-be murderer with her storytelling.

While this framework provides a rich context (most of the aforementioned murderers and heroines make appearances within the book), Oyeyemi’s novel is not a simple retelling of the Bluebeard legend or a bland metafictional exercise in which author becomes character and vice versa. There are no exact parallels or allegorical stand-ins. Through S.J. and Mary’s dueling narratives, Mr. Fox submerses us in a series of inventive, complex worlds, each uniquely voiced and easily standing on its own. Within one story, a young governess and writer enters into a troubling correspondence with a famous author; in another, a Yoruba woman barters with a mysterious man named Reynardine to recover her dead lover. “Hide, Seek” is about an Egyptian boy and his adoptive mother, who are building a woman piece by piece with art works they find all over the world. “Some Foxes” tells of a fox and a young woman who fall in love. The result is nothing short of pyrotechnic: this is classical, magical storytelling at its finest.

S.J. and Mary’s fantastical tales are juxtaposed with real-life scenes from the marriage of S.J. and his wife Daphne, blurring fiction and reality until it’s difficult to distinguish one from the other. The often dangerous fusion of fact and fiction, reality and text, is a recurrent concern in the novel. For S.J., there is no harm in routinely victimizing women in his stories because “[i]t’s not real . . . It’s all just a lot of games.” For Mary, this sets a dangerous precedent. “What you’re doing is building a horrible kind of logic,” she says.

People read what you write and they say, “Yes, he is talking about things that really happen,” and they keep reading, and it makes sense to them. You’re explaining things that can’t be defended, and the explanations themselves are mad, just bizarre — but you offer them with such confidence. It was because she kept the chain on the door; it was because he needed to let off steam after a hard day’s scraping and bowing at work; it was because she was irritating and stupid; it was because she lied to him, made a fool of him; it was because she had to die, she just had to, it makes dramatic sense; it was because “nothing is more poetic than the death of a beautiful woman”; it was because of this, it was because of that. It’s obscene to make such things reasonable.

It’s possible to read in Mary’s impassioned speech the sort of logic that guides Parental Advisory labels, but it becomes clear that Oyeyemi is making the case that the very act of creation, of storytelling and writing, has the potential to be violent and dangerous. The storyteller must understand the gravity of this process, because in creating a story, one is, in a sense, creating him- or herself. We see this repeated several times in Mr. Fox: an abusive father forcibly writes text all over the body of his wife until she leaps about chirping, “Am I in the poem? Or is the poem in me?” In one chilling scene, Mr. Fox himself “remembers” deliberately killing Mary Foxe, only to figure out that he’s recalling a story he once wrote about a jilted lover.

Oyeyemi raises this theme of authorial responsibility without offering any well-defined conclusions. But she is a masterful storyteller, and fearless in creating tales whose conclusions are never as straightforward as “The End.”

Larissa Kyzer lives in Brooklyn and regularly reviews for The L Magazine, Reviewing the Evidence, and Three Percent. She blogs at The Afterword.