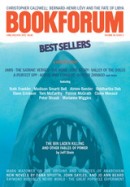

As Hollywood prepares its full-on assault of summer stupidity (I’m looking at you, Green Lantern), Bookforum cleverly devotes its summer issue to best sellers. Ruth Franklin offers an essay about the history of the beast, including its origins:

As Hollywood prepares its full-on assault of summer stupidity (I’m looking at you, Green Lantern), Bookforum cleverly devotes its summer issue to best sellers. Ruth Franklin offers an essay about the history of the beast, including its origins:

The term best seller has always been a misnomer. Fast seller would be more appropriate, since the pace of sales matters as much as the quantity. The first list of books “in order of demand” was created in 1895 by Harry Thurston Peck, editor of the trade magazine The Bookman. Publishers Weekly started its own list in 1912, but others were slow to follow: The New York Times did not create its best-seller list until 1942. Now, the Wall Street Journal and USA Today also compile national lists, and each of the major regional papers has its own — all generated in slightly different ways.

And like most things, the best-seller list used to be more interesting, less predictable:

A combination of factors brought about the homogenization of the best-seller list that began in the late ’70s and continues today. . . .

In the past, it was common for a novelist to have a few hits and then fade from view. [Warwick] Deeping, for instance, never made the list again after 1932, though he continued publishing through the ’50s. Now, by contrast, there began to emerge a core group of writers who could regularly sell a million copies in a year and then come right back the following year with a new best seller — a trend that continued through the ’90s and shows no signs of abating. . . . Danielle Steel — who published her first best seller, Changes, in 1983 — holds the current record with thirty-three. Stephen King, whose first hit was The Dead Zone in 1979, comes in second with thirty-two. John Grisham, who started with The Firm in 1991, is third with twenty-three. Rounding out the list are the prolific newcomer James Patterson (seventeen), Tom Clancy (thirteen), Patricia Cornwell and Sidney Sheldon (eleven each), and Michael Crichton and Robert Ludlum (ten each). Some of these writers are stronger than others — both Clancy and Crichton have at least produced readable books — but none approaches the stature even of a Wouk or a Uris. The middlebrow, represented now by writers like John Irving and Garrison Keillor, had become a minority. Meanwhile, the only new literary novelists who made the list in the ’80s and ’90s did so with the help of movie tie-ins (Umberto Eco) or assassination threats (Salman Rushdie). The “flood of fiction” that Peck lamented in 1902 had become a tsunami drowning out outlier voices.