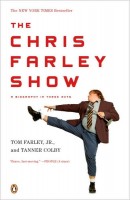

I don’t stick to a strict reading schedule. I’m always buying books, so I always have a lot of books I haven’t read. I imagine this condition will last forever. The unread books are in a constant state of flux, some of them occasionally floating toward the top of the pile, which pile is more mental than physical. Sometimes I will learn about a book or become suddenly interested in one that skips to the front of the line, but few of those books have been as unlikely to do so as The Chris Farley Show, an oral biography of the comedian.

I don’t stick to a strict reading schedule. I’m always buying books, so I always have a lot of books I haven’t read. I imagine this condition will last forever. The unread books are in a constant state of flux, some of them occasionally floating toward the top of the pile, which pile is more mental than physical. Sometimes I will learn about a book or become suddenly interested in one that skips to the front of the line, but few of those books have been as unlikely to do so as The Chris Farley Show, an oral biography of the comedian.

Last week, a friend at work sent me a very brief, silly clip from a Farley movie to expound on some joke we had just made. And in the way of YouTube, I then found myself watching an appearance Farley made on Letterman in 1995. Something about the interview piqued my interest. Or rather, several things: Farley’s agile double-cartwheel entrance; his earnest-fan handshake with the legendary host; his unsurprisingly over-the-top (and possibly intoxicated) but still riveting performance; his strangely child-like responses to certain moments; the way Letterman was genuinely cracking up, which is rare.

Farley died at 33, his popularity far outrunning his resume. There were a handful of good Saturday Night Live characters (like the motivational speaker Matt Foley, and Farley himself as a befuddled interviewer of the stars) and a few funny scenes in Tommy Boy. But in several of his roles, there was a sense that Farley was an actor who could convey a character and not crack up in the middle of whatever outrageous thing he was doing. I don’t think I would be interested in a straight biography of him, but the oral format was perfect. I read it in about a day.

The child-like thing was no act, as Farley had a fairly serious case of arrested development, being mothered from afar after he moved to New York from the Midwest and generally obsequious to all authority figures. He was also obsessive-compulsive. (Writer and performer Bob Odenkirk, who wrote the Matt Foley sketch: “I cannot express to you how much he licked everything. . . . He had to lick his shoelaces to tie them. He’d lick his finger and touch the stair, lick the finger, touch the stair, and do it all the way up the staircase. It was totally nuts.”)

He was also very generous, spending time with some of New York’s most forgotten people. The full extent of his charity work, through his church and other outlets, wasn’t known even by those close to him until after his death.

The middle of the book focuses on Farley’s magnetic stage presence. His friend Pat Finn says of watching him perform at Chicago’s Second City: “There was a scene where he played a waiter. The people eating dinner were the heart of the scene, but Chris came out and got a huge laugh with “Can I get you something to eat?” That was it. He went over to the other side of the stage to make the drinks and the sandwiches in the background, and every single head in the audience slowly turned to watch Chris. It was the oddest thing. Even if he was doing nothing, you wanted to watch him do nothing.” Fellow actor Michael McKean said, “It was nice to share the stage with that kind of manic energy. For one thing, you knew the focus was elsewhere. No one was watching me. I could have sat down and eaten a sandwich during some of the sketches we did together.”

But above everything else, Farley was an addict, and the book moves inexorably toward a series of grim remembrances that end more than once with, “And that was the last time I ever saw him alive.” As his friend Ted Dondanville puts it earlier in the book: “The first hour of drinking with Chris was fun. The second hour was the best hour of your life. The rest of the night was pure hell.” The book mostly reads as a cautionary tale about what you can — and can’t — do to help someone with their own demons. It’s far more harrowing than funny, which seems only right, since that could also be said of Farley’s life off-camera.