Reviewed:

Reviewed:

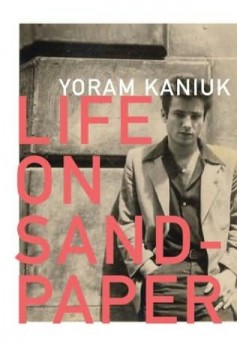

Life on Sandpaper by Yoram Kaniuk

Dalkey Archive Press, 400 pp., $15.95

Could it be that the Great American Novel was written in Hebrew, by an Israeli? This is the unlikely question I kept asking myself while flying through Yoram Kaniuk’s fascinating, moving, beautiful autobiographical novel Life on Sandpaper.

First published in Hebrew in 2003, Life on Sandpaper has been published in a fantastic translation by Anthony Berris. It tells the story of a young artist, Yoram Kaniuk, who has been shot in the leg during the Israeli War of Independence in 1948. He goes to New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital to recuperate, and stays in America for 10 years.

Kaniuk meets and befriends a gallery of 1950s notables, hanging out with Marlon Brando, Robert De Niro (Sr. and Jr.), and James Dean — the latter is fascinated by Kaniuk’s painting, and, for a few weeks, watches him paint for hours each morning — along with jazz musicians like Charlie Parker and Billie Holiday. Kaniuk exudes some kind of exotic charisma — unique, perhaps, to expatriates who have almost been killed before reaching their twenty-first birthday — and men and women seem to love him (many of the women sleep with him). Kaniuk, unlike most everyone else, has the freedom to live like he means it.

The book is both the portrait of an artist as a young man and the portrait of a man growing up, finding himself in a country that is not his own, and, in the process, learning to know the country better than most of its citizens. Here is a representative fragment from the novel, describing Kaniuk’s first day in America:

Gandy played me a Billie Holiday record and said that her voice was like dried-up water. I didn’t know what that meant, but I liked it. He’d sent me a letter in Paris and on the envelope wrote: To Yoram Kaniuk, An Israeli Citizen in Paris. Said I should come. When I arrived he asked me how much money I had. Eight dollars and forty cents, I replied. He seemed disappointed because although he was a Jew he was one of the ones who think that every Jew, apart from him, is wealthy. We took a bus to Manhattan and from there, somewhere around 100 and Something Street, we walked. The sun was shining. It was a beautiful fall day. A pleasant aroma of roasting coffee and flowers and in every store and restaurant the jukeboxes played two songs, “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” or “Stormy Weather,” and I felt I’d come home.

Things happen fast, time flies, and Kaniuk is in Paris and then he is in New York. The book — 400 pages long — has no chapters. There are paragraphs, but one almost feels the novel is composed of one long sentence, and that this is not a bad thing.

The short, staccato sentences in the excerpt above are a hallmark of the book. Written in first person, everything is told as fact. There is little evaluation or discussion of events. Things simply occur. In this way, Life on Sandpaper reminded me of the best of Roberto Bolano, 2666 and The Savage Detectives, but especially the latter. Form is not the only similarity between the two novels and the two novelists. Both authors — and their novelistic counterparts — are at once alone in their adopted countries and the best friend of everybody. Both have a lot of great sex.

Most importantly, both are artists. And while Kaniuk (the character, if not the man) begins Sandpaper as a painter, the book is in some sense about losing or modifying the zest for creation that, when it comes at all, most often comes with youth. He’s a novelist by the novel’s end.

Kaniuk paints a picture of his friend Charlie Parker, the jazz musician, about a month before the musician dies at 34. It is, by his own reckoning, Kaniuk’s best picture. He is forced, for financial reasons, to sell it, and this is how he describes the minutes after the sale:

It was raining hard and I got soaked to the skin, but I couldn’t stop walking. I was overwhelmed by the thought that what I was most worried about was keeping the money in my pocket dry. I got home and hardly ever painted again.

This moment occurs about two-thirds through the novel, and after it the tone is slightly changed. In the first portion of the book, Kaniuk is constantly on the move. He drives across the country, more than once, and travels to South America. He meets and consorts with famous artists, actors, and musicians. Then he sells his self-proclaimed masterpiece, and something within him changes. The cameos of the rich and the famous for the most part cease. The easy life that Kaniuk has led somehow gives way, as he gets involved in several failing get rich quick schemes. He still creates — he is always an artist at heart — but the nature of his creation perceptibly changes.

There is a clear loss here, but also a significant gain. The shedding of one art form, the visual, leads to the wild embrace of the written word. As Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man chronicled the creation of an artist, Kaniuk tells the tale — just as beautiful — of the metamorphosis of one.

Bezalel Stern is a writer and lawyer who lives in New York. Read more at bezalelstern.tumblr.com.

Mentioned in this review: